On Tuesday, self-described wonk Rick Snyder used much of his State of the State speech to take responsibility for poisoning Flint’s children. Though by the end of the week, Snyder was limiting the extent of his responsibility because the “experts” didn’t exercise “common sense.” (See video here.)

“The department people, the heads, were not being given the right information by the quote-unquote experts, and I use that word with great trial and tribulation because they were considered experts in terms of their background, these are career civil servants that had strong science, medical backgrounds in terms of their research,” Snyder said. “But as a practical matter, when you look at it today and you look at their conclusions, I wouldn’t call them experts anymore.”

[snip]

This is something that we don’t consider just what one person did, let’s look at the entire cultural background of how people have been operating,” Snyder said. “Let’s get in there and rebuild the culture that understands common sense has to be part of it, taking care of our citizens has to be part of it.”

[snip]

The Republican governor added: “What’s so frustrating and makes you so angry about this situation is you have a handful of quote-unquote experts who were career service people that made terrible decisions in my view and we have to live with the consequences with that. They work for me, so I accept that responsibility.”

It’s a very curious argument for a guy who — still! — gets treated as someone who puts policy over ideology, in spite of the years of serving as Dick DeVos’ puppet approving of bad policy over and over. (In the same appearance, Snyder took credit for things President Obama’s Administration has given to Flint, including Medicaid expansion under ObamaCare, but that’s a long-standing schtick of this governor.) Effectively, a guy whose entire political gimmick is that he relies on experts is now saying those damned experts didn’t exercise enough common sense.

Yes, Governor. The experts did not exercise enough common sense.

But something else Snyder did this week drives me even crazier than his equivocation over wonkdom, just as it became clear his particular approach to policy — especially his insistence that emergency managers can fix the pervasive problems of Michigan’s cities — had poisoned Flint’s children.

Rick Snyder channeled Jerry Lewis, the telethon guy.

In the middle of his speech — and in his website dedicated to this issue — Snyder solicited donations.

If you’d also like to aid Flint, please go to HelpForFlint.com to volunteer or donate. If you are a Flint resident who needs help getting the water you need, go to HelpForFlint.com.

Hell, Snyder’s not even as competent as Jerry Lewis! Because while two of the links Snyder includes on his site go to sites dedicated to helping the people of Flint deal with this crisis — one to Greater Flint’s Community Foundation and the other to a United Way fund specifically set up to benefit Flint — Snyder’s third donate link goes to the Red Cross’ general SE MI site, such that any funds donated might go to other entirely worthy causes but not Flint.

Anyway, here’s why this has been bothering me all week.

First of all, Rick Snyder is worth something like $200 million, and while he returns his gubernatorial salary, he brings in around $1.9 million a year. So this is a guy making making $36,500 a week asking people who (using the Michigan average household, not individual, income) $48,500 a year to donate to help Flint. Your average Michigan household is doing almost twice as well as your average Flint household (average $25,000 a year) — so it is certainly within their charitable ability to help their fellow Michigander. But clearly the kinds of donations that Rick Snyder could afford would go much further to helping Flint than the kind of donations most Michiganders could afford.

But here’s the more galling thing.

We got into this position because Michigan (under a Democrat, originally, but expanded under Snyder, than reinforced after voters of Michigan rejected that approach) has decided to deal with the ills of its cities a certain way. Not only doesn’t the state help out, it instead has shifted revenue sharing away from cities, which has created fiscal emergencies in many of them, which Snyder has then used to bring in state appointed “experts” to dictate to the locals what to do. The measure of those outsiders is always “fiscal responsibility,” not overall well-being or even fiscal sustainability (or what some people might call “common sense”). The result is that — with the possible except of Detroit (though even there, the human cost has been breathtaking) — city after city sells common property off and takes away services, including things like policing and … clean water … as a way to meet those fiscal responsibility goals. Many of the cities so treated — Flint is one of but not the only archetype — keep having serial emergencies without any solutions to the underlying problems of disinvestment and segregation.

It was only a matter of time before the state’s emergency managers started doing real damage to the people living in the cities as a result (and the damage Snyder’s serially experimenting and corrupt state-led schooling replacement has been at least as bad).

From my understanding, Michigan has decided to approach its cities this way for two reasons. First, segregation: Michigan is a badly segregated state (though on that count, Flint is nowhere near as bad as many cities in Michigan). And for too long, Michigan’s politicians — Democratic and Republican — have shied away from from sharing state resources broadly, for either services or schooling, which has meant that as white flight left cities without revenue bases and as globalization hit Michigan more generally, those cities spiraled downward. Quite simply, the state wouldn’t do what Snyder wants to Michiganders to do informally, share between the more fortunate and the less fortunate.

How bizarre is that?!?! That Snyder thinks we more fortunate Michiganders should share with the less fortunate (we should!!), but he won’t use policy to make it happen?!?!? Effectively, he is suggesting the well-being of some of the state’s children should be at the whim of charity, not government policy.

But the other reason Snyder pushed through his initial emergency manager law and then re-upped it after voters rejected it is to enable certain kinds of policy outcomes. The best known of those is the breaking of the unions and with it the slashing of both wages and pensions that used to provide a middle class living for many public servants. But in some cases, the ability to have an appointed manager make decisions based solely on economic responsibility has made it easier to loot those cities, a golf course here, an art museum there, much of a downtown there. And both the ideological outcome — busting the unions — and the looting have beneficiaries, people like Dick DeVos (net worth $6.9 billion, and whose ideological goals Snyder has placed ahead of Michigan’s well-being) and Quicken Loans owner Dan Gilbert (net worth $3.7 billion). Gilbert, in particular, has benefitted coming and going, as he got to influence how properties, including foreclosures his own company owned in Detroit, got dealt with.

And of course, Snyder pushed his expanded emergency manager approach to solving the problems of cities like Flint even while he was cutting taxes for businesses like DeVos’ Amway and Gilbert’s Quicken.

So, even at a moment when his preferred approach to dealing with real problems of a manufacturing state like Michigan resulted in the poisoning of Flint’s children, Snyder was calling for charity rather than demanding that the policy of the state ask its billionaires to invest in cities rather than looting them. (It’s important to note Grand Rapids is better off than almost any other Michigan city in two ways: it is not majority African American, and it benefits handsomely from Meijer, DeVos and fellow Amway billionaire Van Andel family investments in the city, giving us access to arts and sports opportunities most cities of our size would not have).

Which brings me to one thus far enduring mystery about the Flint crisis.

There was one moment during this crisis when Snyder asked his rich beneficiaries to pony up some charity rather than asking the middle class.

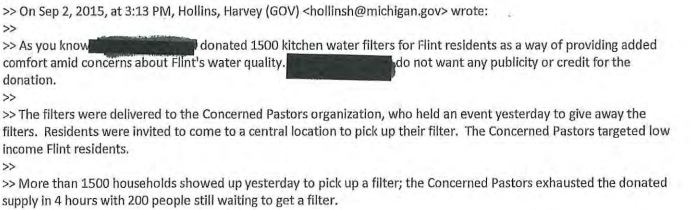

Last year, at a time when the State acknowledged there were probable carcinogens in Flint’s water but still maintained any lead in the water reflect normal seasonal variation (!!), Snyder brokered the donation by a still unnamed corporation of 1,500 water filters to some faith leaders in Flint.

Dave Murray, a spokesman for Snyder, confirmed that the filters, distributed by the Concerned Pastors for Social Action, came from a “corporate donor that does not wish to be recognized but cares deeply about the community.”

The donor “worked with the governor to provide 1,500 faucet filters to be distributed to city homes,” Murray said in an email.

The state’s involvement in the filter distribution was never publicized and pastors told The Flint Journal-MLive Tuesday, Sept. 29, that they were asked by staffers in the governor’s office not to speak about it.

[snip]

“Those filters came from the governor,” Poplar said. “The governor seems to be the one with the golden key” to make something happen, she said.

Pastors involved with the giveaway of the filters, which were designed to remove total trihalomethanes (TTHM) as well as lead from water, said they accepted the condition that they not discuss the state’s role in securing the equipment, said the Rev. Allen Overton.

Overton and the Rev. Alfred Harris said they thought the arrangement was odd, but did not want to jeopardize receiving the water filters, which Flint residents waited in line for and which were given away in just three hours.

Now, the most likely corporate donor, both because of its potential liability for the fouling of the Flint River and because it obviously was testing the water the city of Flint was releasing, would be GM. Though that doesn’t seem to match the redactions in the emails released earlier this week. (See PDF 65)

But I find it remarkable that the only time Snyder has actually asked any big money entities to donate in this affair was at a time when he was trying to make it all go away by shutting up the activists and leading a small portion of residents to feel better about the taste and appearance (though not necessarily the content) of their water.

That donation, like Snyder’s appeal for a sense of common good not backed by actual policy, was all show.

![[image: Sarah G via Flickr]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2949220013_d17943cf23_z-300x201.jpg)

![[image: Eugenia Vlasova via Flickr]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Pacski_EugeniaVlasova-Flickr-300x200.jpg)