Department of Pre-Crime, Part 3: What Law Would the Drone (and/or Targeted Killing) Court Interpret?

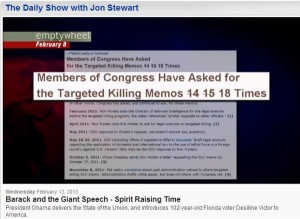

I’ve been writing about the nascent plan, on the part of a few Senators who want to avoid hard decisions, to establish a FISA Court to review Drone (and/or Targeted Killings) of American citizens.

A number of people presumably think it’d be easy. Just use the AUMF — which authorizes the President “to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States” — and attach some kind of measure of the seriousness of the threat, and voila! Rubber-stamp to off an American.

And while that may while be how it would work in practice, even assuming the reviews would be halfway as thorough as the Gitmo habeas cases (with the selective presumption of regularity for even obviously faulty intelligence reports adopted under Latif, as well as the “military age male” standard adopted under Uthman, habeas petitions are no longer all that meaningful), that would still mean the Executive could present any laughably bad intelligence report showing a military aged male was hanging around baddies to be able to kill someone. The Gitmo habeas standard would have authorized the killing of Abdulrahman al-Awlaki, in spite of the fact that no one believes he was even a member of AQAP.

Then there’s the problem introduced by the secrecy of the Drone (and/or Targeted Kiling) Court. One of the several main questions at issue in US targeted killings has always been whether the group in question (AQAP, in the case of Anwar al-Awlaki, which didn’t even exist on 9/11) and the battlefield in question (Yemen, though the US is one big question) is covered by the AUMF.

Congress doesn’t even know the answers to these questions. The Administration refuses to share a list of all the countries it has already used lethal counterterrorism authorities in.

So ultimately, on this central issue, the Drone (and/or Targeted Killing) Court would have no choice but to accept the Executive’s claims about where and with whom we’re at war, because no list exists of that, at least not one Congress has bought off on.

There’s an even more basic problem, though. John Brennan has made it crystal clear that we pick imminent threats not because of any crime they might have committed in the past, but because of future crimes they might commit in the future.

BRENNAN: Senator, I think it’s certainly worth of discussion. Our tradition — our judicial tradition is that a court of law is used to determine one’s guilt or innocence for past actions, which is very different from the decisions that are made on the battlefield, as well as actions that are taken against terrorists. Because none of those actions are to determine past guilt for those actions that they took. The decisions that are made are to take action so that we prevent a future action, so we protect American lives. That is an inherently executive branch function to determine, and the commander in chief and the chief executive has the responsibility to protect the welfare, well being of American citizens. So the concept I understand and we have wrestled with this in terms of whether there can be a FISA-like court, whatever — a FISA- like court is to determine exactly whether or not there should be a warrant for, you know, certain types of activities. You know…

KING: It’s analogous to going to a court for a warrant — probable cause…

(CROSSTALK)

BRENNAN: Right, exactly. But the actions that we take on the counterterrorism front, again, are to take actions against individuals where we believe that the intelligence base is so strong and the nature of the threat is so grave and serious, as well as imminent, that we have no recourse except to take this action that may involve a lethal strike.

What law is it that describes what standards must be met to declare someone a pre-criminal?

Either there are no standards and the Drone (and/or Targeted Killing) Court would just have to take the Administration’s say-so — in which case it’s absolutely no improvement over the status quo.

Or, the courts would make up the standards as they go along, pretty much like the DC Circuit has been in habeas cases. But those standards would be secret, withheld from Americans in the same way the secret law surrounding Section 215 is.

Finally, there’s one more problem with assuming the AUMF provides a law the Drone (and/or Targeted Killing) Court would use to adjudicate pre-crime. The Administration has made it crystal clear that it believes it has two sources of authority for targeted killings; the AUMF and Article II. Which has another implication for a Drone (and/or Targeted Killing) Court.

The Executive has already said that the if the President authorizes the CIA to do something — like murder an American citizen overseas — it does not constitute a violation of laws on the books, like 18 USC 1119, which prohibits the murder of Americans overseas. The Administration has already said that the President’s Article II power supercedes laws on the books. What is a Drone (and/or Targeted Killing) Court supposed to do in the face of such claims?

This carries a further implication. If the Court were using the AUMF as its guide to rubber-stamping the President’s kill list, nothing would prevent the Executive from killing someone outside of that Court on its claimed Article II authority.

Until we make it clear that unilateral murder of American citizens is not an Article II authority, the President will keep doing it, whether there’s a Court or not.

Previous posts on the Pre-Crime Court:

Setting Up a Department of Pre-Crime, Part One: Why Are We Doing This?