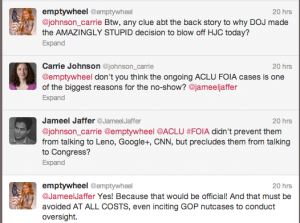

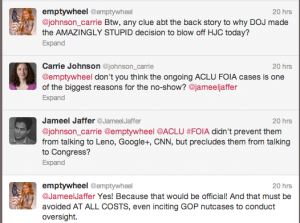

NPR’s Carrie Johnson, ACLU’s Jameel Jaffer, and I discussed yesterday whether the Administration decided to blow off the House Judiciary Committee panel on targeted killing because appearing and answering questions might compromise their uncompromising stance in the targeted killing FOIA.

NPR’s Carrie Johnson, ACLU’s Jameel Jaffer, and I discussed yesterday whether the Administration decided to blow off the House Judiciary Committee panel on targeted killing because appearing and answering questions might compromise their uncompromising stance in the targeted killing FOIA.

It’s a point Ben Wittes made in a response to my query from yesterday,

I can’t imagine what kind of stupidity drove the decision to blow off the committee.

(Note, thanks to Wittes for displaying my potty-mouth in its well-celebrated glory; MSNBC Lawfare is not.)

In which he suggests both John Brennan’s nomination and ACLU’s FOIA may have driven that decision.

I can imagine two reasons, though I agree with Marcy that it was stupid—and, I will also add, wrong—of the administration to stiff the committee. The first is John Brennan’s pending confirmation. The last thing administration wants right now, prior to a Senate vote on Brennan, is to create a forum in which officials get more questions on targeted killings.

The second reason, as I said at the hearing, is FOIA litigation. Every disclosure prompts more demands for more disclosures and prompts arguments that material is not, in fact, secret. So there’s a hunker-down-and-say-nothing mentality that has kicked in. As I say, it’s wrong. And as the tone of yesterday’s hearing—where Republicans and Democrats alike were clamoring for judicial review of targeting decisions—shows, the administration has a lot of work to do with Congress if it means to maintain confidence in its policies—work that will have to be done, at least in part, in public. But it’s not hard, in my opinion, to imagine what’s behind it.

First, with regards to Brennan’s nomination, I present this:

The Senate intelligence committee on Wednesday postponed until next week a vote on the confirmation of White House aide John Brennan to be CIA director, dashing hopes of Democratic leaders who had hoped to have a vote on Thursday.

[snip]

No explanation for the delay was immediately available. However, the Obama administration has been at odds with members of the committee’s Democratic majority over White House unwillingness to disclose some highly classified legal documents related to “targeted killings,” including the use of lethal drone strikes against suspected militants.

[snip]

On Wednesday, administration officials met with intelligence committee members to discuss the contents of the disputed documents. Copies of the material were not turned over to the committee, however, said a source familiar with the matter.

On Tuesday, the Administration shared the Benghazi emails with the Benghazi Truthers, which had been their plan to move Brennan’s nomination forward without turning over any more memos. And while some Republicans, just moments after they received the emails, made a mild stink about Brennan’s thoroughly predictable involvement in efforts to craft talking points about the attack, by Wednesday, that already proved insufficient to move the nomination.

By Wednesday, the Administration was sharing more information on the memos, not Benghazi. And then, after sharing such information, we learn the Administration has been left to stew over the weekend.

Now, perhaps the leaks to National Journal changed the game:

A senator who sits on the Intelligence Committee and has read some of the memos also said that the still-unreleased memos contain secret protocols with the governments of Yemen and Pakistan on how targeted killings should be conducted. Information about these pacts, however, were not in the OLC opinions the senator has been allowed to see. The senator, who also would speak to National Journal only on condition of anonymity, said the only memos that the committee has been given represent mainly legal analysis justifying the drone strikes, and that the rest contain “case-specific” facts about operations.

In response to which an anonymous official who looks like Tommy Vietor made dickish comments about how unreasonable it would be to let the Senate Intelligence Committee exercise oversight and how mean it is to use confirmations to insist on being able to do so because it just feeds into Republican plots.

An Obama administration official who is familiar with the negotiations with Feinstein’s committee indicated that the White House was miffed at efforts by the senator and her staff to obtain all the memos at once, because such efforts play into the Republican strategy of using the dispute to delay the confirmation of John Brennan, Obama’s nominee to head the CIA and the main architect of the drone program, as well as Chuck Hagel as Defense secretary.

“These guys don’t even know what the hell they’re asking for,” the official said. “They think they can ‘reverse-engineer’ the [drone] program by asking for more memos, but these are not necessarily things that exist or are relevant…. What they’re asking for is to get more people read into very sensitive programs. That’s not a small decision.”

Perhaps senior administration officials leaking information presumably contained in the memos to the NYT didn’t help matters.

And while lofty Senators on Intelligence Committees usually couldn’t give a damn about lowly Congressman on Judiciary Committees, I can’t imagine yesterday’s hearing helped. Because in that hearing, a bunch of very partisan Republicans made a case that will be credible to moderates and civil libertarians like me (not to mention, really feed the Tea Partiers) that the Administration is abusing its power, both in regards to the way it is treating Congress, but also in its claims to potentially unchecked authority. (Note, on that front, I owe HJC Chair Bob Goodlatte an apology: it was a well-run and well-crafted hearing.)

With the Talking Point emails shared, Benghazi is frittering out, and the Republicans will need a new scandal to fundraise off of. And a potential fight over whether or not the President has to say whether he thinks he can kill Americans in America has the distinct advantage over both Fast and Furious (their most successful scandal to date) and Benghazi (which wasn’t nearly as successful) in that people across the political spectrum (save those who think Obama should be trusted with this authority because, well, he’s trustworthy) may think it’s reasonable.

That is, while (some) Republicans may only be picking this up because it demonstrates the Administration’s double standard with respect to the Bush Administration, or because their prerogatives have been slighted, or because they figure this paranoid level of secrecy might be hiding real misconduct, the targeting killing memos are close to reaching a tipping point at which they turn into a real political issue.

And that may be what the Administration will be stewing over this weekend.

In the face of that threat, then, there’s just the FOIA. Mean old ACLU Legal Director Jameel Jaffer, FOIAing for more information on the President’s authority to kill Americans (and also, it should be said, helping the Awlaki and Khan families sue for wrongful death). How dare he do that, even if John Brennan, in one of the Administration’s key counterterrorism speeches, emphasized how important presumptive disclosure on FOIA was?

Our democratic values also include—and our national security demands—open and transparent government. Some information obviously needs to be protected. And since his first days in office, President Obama has worked to strike the proper balance between the security the American people deserve and the openness our democratic society expects.

[snip]

The President also issued a Freedom of Information Act Directive mandating that agencies adopt a presumption of disclosure when processing requests for information.

So what if John Brennan says the terrorists will win if the Administration plays stupid games with FOIA? There are lawsuits to be won, damnit!

Now, I have no doubt that the Administration might delay Congressional oversight solely to gain an advantage over the ACLU. Not only did Daniel Klaidman’s sources reveal such suits were at the forefront of their considerations when deciding not to be as transparent as promised, but it appears the Administration already delayed Congressional oversight so as to gain an advantage in ACLU’s FOIA suit.

So yes, it is likely that is one of the reasons DOJ chose to snub the Committee, thereby making this issue more of a political issue.

But it seems the Administration has lost all perspective about how those FOIAs might play out. That’s true, as Jack Goldsmith pointed out, because even if a judge rules that the Administration has revealed what it has been trying to avoid revealing, it’s not the end of the FOIA world for them.

But what if the Court does rule that the USG has acknowledged CIA’s involvement in drone strikes? What would the ACLU gain, since the whole world already knows this fact? Such a ruling would require CIA to file a Vaughn index listing responsive documents to the CIA request. But at that point the government would have further legal options for non-disclosure. As I once explained:

Even if the D.C. Circuit concludes that the USG has in effect officially acknowledged CIA involvement in drone strikes, however, it need not follow that the CIA must cough up a list of all responsive documents. These lists alone – which typically contain document titles, dates, and the like – can disclose quite a lot about what the CIA is doing. Some of the information in a Vaughn index might reveal or point to sources and methods or other properly classified information that would harm national security. I see no reason why the D.C. Circuit could not rule that the USG has acknowledged CIA involvement, but then rule that (a) the CIA need not produce a Vaughn index if doing so would disclose properly classified information, or (b) the CIA must produce a Vaughn index but can redact any entries in the index (including all of them) that would, if revealed, disclose properly classified information. Option (a) was suggested by Judge Easterbrook in Bassiouni v. CIA, 392 F. 3d 244 (7th Cir. 2005) – an approach that, as Easterbrook noted, is entirely consistent with the FOIA statute. Option (b) is simply a more fine-grained substitute for the Easterbrook approach that would force the government to explain its redactions (and which need be no trickier than the already-tricky process of forcing the government to explain why the documents referenced in a Vaughn index need not be disclosed).

Even if ACLU wins on the “official acknowledgment” issue, in short, it has a long way to go to get the records it seeks. But as we have seen more than once in the last decade, even heavily redacted Vaughn indexes can reveal important information and constitute the basis for further FOIA requests and further disclosures (through FOIA or other means).

I’d add that, at least in the 2nd Circuit, the Administration seems to be protected by overly broad protection for the Memorandum of Notification that authorizes targeted killing and everything else.

And unless there are really big disclosures in there that even I can’t imagine (plus, who besides me is going to look that closely?), there’s simply nothing that will come out in FOIA that will be more damaging than inciting the Republicans to turn this — a real example of abuse of power — into their next political scandal.

Trust me, Obama folks, you made the wrong calculation here, and you’d do well to reverse course before it’s too late.

Though I will make one final caveat.

I don’t think the FOIA could be all that damaging to the Administration.

But I do think the wrongful death suit might. This discussion will make it very hard for the Administration to dismiss of this counterterrorism suit the same way they have every other one, by invoking state secrets (and while there might be standing issues, particularly for Nasser al-Awlaki, Sam Alito won’t be able to suggest the Awlakis and Khans can’t prove their family members were killed in a US drone strike). And having lost the veil of state secrets, there are all sorts of issues that might come out, both about Awlaki’s history, and about why the FBI let Samir Khan leave when every other known radical trying to head to Yemen gets arrested before he boards a plane.

And, quite simply, if they can’t prevent Khan from pursuing this wrongful death suit, some interesting legal conclusions.

So while I think to the extent the Administration is still stalling Congress because of the FOIA, they’re crazy. If that’s the case, they’d be risking giving Republicans a really dangerous issue to politicize next.

All that said, I think the wrongful death suit may present real issues for them, particularly as this information becomes more public. But if it does, then it just serves to prove that the case for killing Awlaki and Khan and Abdulrahman doesn’t withstand legal review.