American Drone War: Murder and Democracy

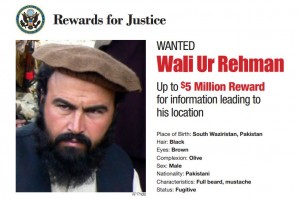

In his post on the drone killing of Waliur Rehman Mehsud earlier this week, Jim noted that CIA has sworn revenge for the 2009 Pakistani Taliban supported suicide attack on CIA’s base in Khost.

Sure enough, one of the things Press Secretary Jay Carney mentioned when asked about the strike yesterday was Rehman’s role in the “murder” of 7 CIA officers in Khost in 2009.

While we are not in the position to confirm the reports of Waliur Rehman’s death, if those reports were true or prove to be true, it’s worth noting that his demise would deprive the TTP — Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan — of its second in command and chief military strategist. Waliur Rehman has participated in cross-border attacks in Afghanistan against U.S. and NATO personnel and horrific attacks against Pakistani civilians and soldiers. And he is wanted in connection to the murder of seven American citizens on December 30, 2009, at Forward Operating Base Chapman in Khost, Afghanistan.

Now, I’m sorry that 7 CIA officers died, but let’s consider what it means that the US continues to call the attack murder.

As I noted almost 3 years ago when DOJ first sanctioned TTP and indicted Hakimullah Mehsud, the notion that they should be legally held responsible — in the US, at least — for “murder” is laughable. The Khost attack took place after an extended campaign to kill Baitullah Mehsud, as Jane Mayer recounts.

Still, the recent [in 2009] campaign to kill Baitullah Mehsud offers a sobering case study of the hazards of robotic warfare. It appears to have taken sixteen missile strikes, and fourteen months, before the C.I.A. succeeded in killing him.

[snip]

On June 14, 2008, a C.I.A. drone strike on Mehsud’s home town, Makeen, killed an unidentified person. On January 2, 2009, four more unidentified people were killed. On February 14th, more than thirty people were killed, twenty-five of whom were apparently members of Al Qaeda and the Taliban, though none were identified as major leaders. On April 1st, a drone attack on Mehsud’s deputy, Hakimullah Mehsud, killed ten to twelve of his followers instead. On April 29th, missiles fired from drones killed between six and ten more people, one of whom was believed to be an Al Qaeda leader. On May 9th, five to ten more unidentified people were killed; on May 12th, as many as eight people died. On June 14th, three to eight more people were killed by drone attacks. On June 23rd, the C.I.A. reportedly killed between two and six unidentified militants outside Makeen, and then killed dozens more people—possibly as many as eighty-six—during funeral prayers for the earlier casualties. An account in the Pakistani publication The News described ten of the dead as children. Four were identified as elderly tribal leaders. One eyewitness, who lost his right leg during the bombing, told Agence France-Presse that the mourners suspected what was coming: “After the prayers ended, people were asking each other to leave the area, as drones were hovering.” The drones, which make a buzzing noise, are nicknamed machay (“wasps”) by the Pashtun natives, and can sometimes be seen and heard, depending on weather conditions. Before the mourners could clear out, the eyewitness said, two drones started firing into the crowd. “It created havoc,” he said. “There was smoke and dust everywhere. Injured people were crying and asking for help.” Then a third missile hit. “I fell to the ground,” he said.

When CIA finally got Baitullah, they also took out his young new bride.

The people Humam al-Balawi took out at Khost were all, as far as is known, active participants in the drone campaign that created all this carnage. As NYU’s Sarah Knuckey laid out yesterday, the Khost attack is probably murder under Afghan law, but not under international law, which would count CIA drone killers as civilians directly participating in hostilities.

In an international armed conflict (IAC), members of the armed forces have combatant immunity and combatant privilege. Meaning: they can kill the other side’s combatants (if rules on killing satisfied in individual case), AND, they cannot be prosecuted under domestic law (of their enemy, if e.g., they were captured) for a killing that was permitted under IHL. They could be tried by the capturing enemy for any violation of IHL, e.g. war crimes.

But, this immunity only attaches to members of the armed forces. It does not apply to “civilians who directly participate in hostilities [DPH]” (e.g the farmer who picks up arms to fight the Americans one day, the US civilian – yes, including any CIA officer who “directly participates”). So, a CIA officer (not any of them, only those DPH’ing, eg. involved in, say, drone strikes, or night raids) could, under the laws of war, be arrested and tried in Afghanistan or Pakistan, and tried for murder under domestic law. (This is so, even if the “murder” was permitted by IHL). Ditto for some AQ or Taliban member – they have no immunity. Their killing might be permitted by IHL, but not by Afghan law. Whether the Khost killings violated Afghan criminal law, I don’t know (haven’t studied the Afghan crim code), but I’d assume yes.

In other words, calling Khost “murder” simply imposes a double standard, in which we’re allowed to kill scores of civilians, including funeral goers and young wives not directly participating in combat, but those DPHs are not allowed to strike back.

But that’s not the only thing that likely went on with this strike. As McClatchy lays out (and Jim also hinted at) it was probably just as much an effort to thwart peace discussions between the civilian government of Pakistan and the Pakistani Taliban.

Waliur Rehman Mehsud’s death comes just before the assumption of power next month of a government led by Nawaz Sharif, a center-right politician who’ll become the prime minister for a record third time. Sharif based his appeal partly on his demand for an end to drone strikes and a pledge to seek peace talks with the Pakistani Taliban.