Information Monopoly Defines the Deep State

The last decade witnessed the rise of deep state — an entity not clearly delineated that ultimately controls the military-industrial complex, establishing its own operational policy and practice outside the view of the public in order to maintain its control.

The last decade witnessed the rise of deep state — an entity not clearly delineated that ultimately controls the military-industrial complex, establishing its own operational policy and practice outside the view of the public in order to maintain its control.

Citizens believe that the state is what they see, the evidence of their government at work. It’s the physical presence of their elected representatives, the functions of the executive office, the infrastructure that supports both the electoral process and the resulting machinery serving the public at the other end of the sausage factory of democracy. We the people put fodder in, we get altered fodder out — it looks like a democracy.

But deep state is not readily visible; it’s not elected, it persists beyond any elected official’s term of office. While a case could be made for other origins, it appears to be born of intelligence and security efforts organized under the Eisenhower administration in response to new global conditions after World War II. Its function may originally have been to sustain the United States of America through any threat or catastrophe, to insure the country’s continued existence.

Yet the deep state and its aims may no longer be in sync with the United States as the people believe their country to be — a democratic society. The democratically elected government does not appear to have control over its security apparatus. This machinery answers instead to the unseen deep state and serves its goals.

As citizens we believe the Department of State and the Department of Defense along with all their subset functions exist to conduct peaceful relations with other nation-states while protecting our own nation-state in the process. Activities like espionage for discrete intelligence gathering are as important as diplomatic negotiations to these ends. The legitimate use of military force is in the monopolistic control of both Departments of State and Defense, defining the existence of a state according to philosopher Max Weber.

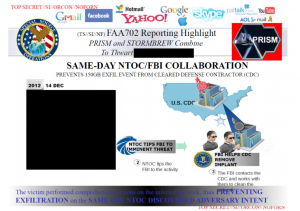

The existing security apparatus, though, does not appear to function in this fashion. It refuses to answer questions put to it by our elected representatives when it doesn’t lie to them outright. It manages and manipulates the conditions under which it operates through implicit threats. The legitimacy of the military force it yields is questionable because it cannot be restrained by the country’s democratic processes and may subvert control over military functions.

Further, it appears to answer to some other entity altogether. Why does the security apparatus pursue the collection of all information, in spite of such activities disrupting the ability of both State and Defense Departments to operate effectively? Why does it take both individuals’ and businesses’ communications while breaching their systems, in direct contravention to the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment prohibition against illegal search and seizure? Read more →

![[photo: Gwen's River City Images via Flickr]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/StalkerWindow_GwensRiverCityImages-Flickr.jpg)