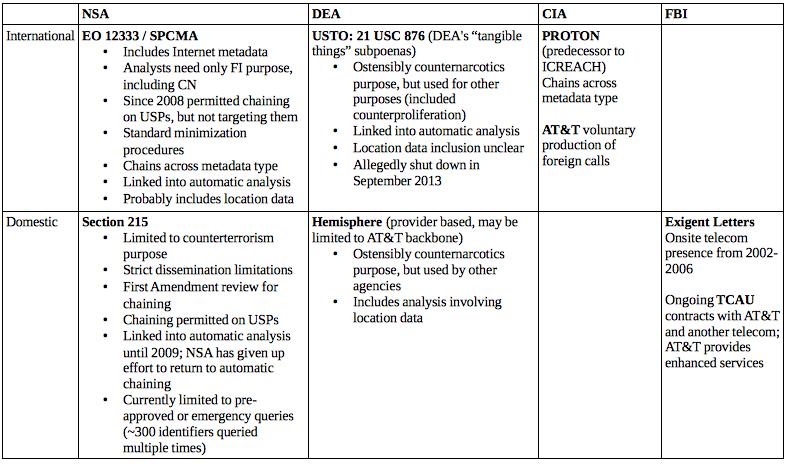

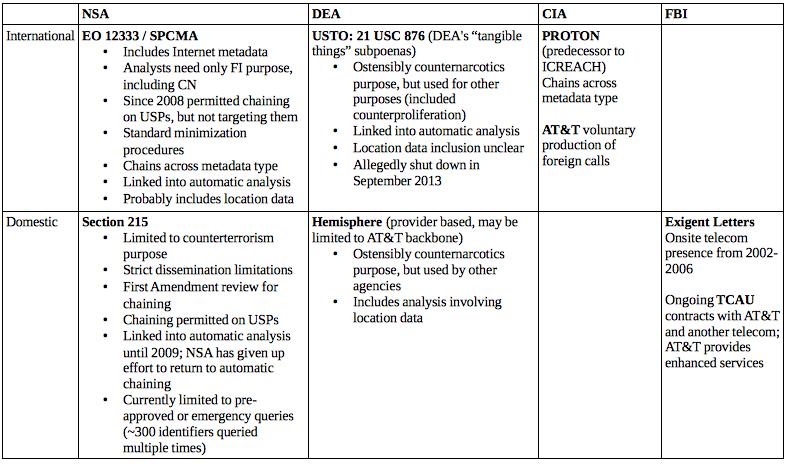

I’ve been laying this explanation out since USA Today provided new details on DEA’s International Dragnet, but it’s clear it needs to be done in more systematic fashion, because really smart people continue to mistakenly treat the Section 215 database as the analogue to the DEA dragnet described by USAT, which it’s not. There are at least five known telecommunications dragnets (some of which appear to integrate other kinds of metadata, especially Internet metadata). Here’s a quick guide to what is known about each (click to enlarge, let me know of corrections/additions, I will do running updates to make this more useful):

NSA, International

When people think about the NSA dragnet they mistakenly think exclusively of Section 215. That is probably the result of a deliberate strategy from the government, but it leads to gross misunderstanding on many levels. As Richard Clarke said in Congressional testimony last year, Section “215 produces a small percentage of the overall data that’s collected.”

Like DEA, NSA has a dragnet of international phone calls, including calls into the United States. This is presumably limited only by technical capability, meaning the only thing excluded from this dragnet are calls NSA either doesn’t want or that it can’t get overseas (and note, some domestic cell phone data may be available offshore because of roaming requirements). David Kris has said that what collection of this comes from domestic providers comes under 18 U.S.C. § 2511(2)(f). And this dragnet is not just calls: it is also a whole slew of Internet data (because of the structure of the Internet, this will include a great deal of US person data). And it surely includes a lot of other data points, almost certainly including location data. Analysts can probably access Five Eyes and other intelligence partner data, though this likely includes additional restrictions.

There are, within this dragnet, two sets of procedures for accessing it. There is straight EO 12333, which appears to defeat US person data (so if you’re contact chaining and a known US person is included in the chain, you won’t see it). This collection requires only a foreign intelligence purpose (which counternarcotics is explicitly included in). Standard NSA minimization procedures apply, which — given that this is not supposed to include US person data — are very permissive.

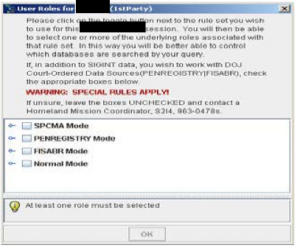

Starting in 2008 (and probably before 2004, at least as part of Stellar Wind), specially-trained analysts are also permitted to include US persons in the contact chaining they do on EO 12333 data, under an authority call “SPCMA” for “special procedures.” They can’t target Americans, but they can analyze and share US person data (and NSA has coached analysts how to target a foreign entity to get to the underlying US data). This would be treated under NSA’s minimization procedures, meaning US person data may get masked unless there’s a need for it. Very importantly, this chaining is not and never was limited to counterterrorism purposes — it only requires a foreign intelligence purpose. Particularly because so much metadata on Americans is available overseas, this means NSA can do a great deal of analysis on Americans without any suspicion of criminal ties.

Both of these authorities appear to link right into other automatic functions, including things like matching identities (such that it would track “emptywheel” across all the places I use that as my uniquename) and linking directly up to content, if it has been collected.

NSA, Domestic

Then there is the Section 215 dragnet, which prior to 2006 was conducted with telecoms voluntarily producing data but got moved to Section 215 thereafter; there is a still-active Jack Goldsmith OLC opinion that says the government does not need any additional statutory authorization for the dragnet (though telecoms aside from AT&T would likely be reluctant to do so now without liability protection and compensation).

Then there is the Section 215 dragnet, which prior to 2006 was conducted with telecoms voluntarily producing data but got moved to Section 215 thereafter; there is a still-active Jack Goldsmith OLC opinion that says the government does not need any additional statutory authorization for the dragnet (though telecoms aside from AT&T would likely be reluctant to do so now without liability protection and compensation).

Until 2009, the distinctions between NSA’s EO 12333 data and Section 215 were not maintained. Indeed, in early 2008 “for purposes of analytical efficiency,” the Section 215 data got dumped in with the EO 12333 data and it appears the government didn’t even track data source (which FISC made them start doing by tagging each discrete piece of data in 2009), and so couldn’t apply the Section 215 rules as required. Thus, until 2009, the Section 215 data was subjected to the automatic analysis the EO 12333 still is. That was shut down in 2009, though the government kept trying to find a way to resume such automatic analysis. It never succeeded and finally gave up last year, literally on the day the Administration announced its decision to move the data to the telecoms.

The Section 215 phone dragnet can only be used for counterterrorism purposes and any data that gets disseminated outside of those cleared for BRFISA (as the authority is called inside NSA) must be certified as to that CT purpose. US person identifiers targeted in the dragnet must first be reviewed to ensure they’re not targeted exclusively for First Amendment reasons. Since last year, FISC has pre-approved all identifiers used for chaining except under emergencies. Though note: Most US persons approved for FISA content warrants are automatically approved for Section 215 chaining (I believe this is done to facilitate the analysis of the content being collected).

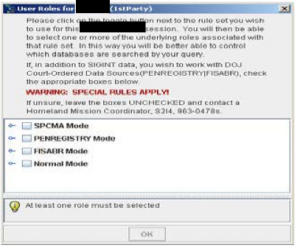

Two very important and almost universally overlooked points. First, analysts access (or accessed, at least until 2011) BRFISA data from the very same computer interface as they do EO 12333 data (see above, which would have dated prior to the end of 2011). Before a chaining session, they just enter what data repositories they want access to and are approved for, and their analysis will pull from all those repositories. Chaining off data from more than one repository is called a “federated” query. And the contact chaining they got — at least as recently as 2011, anyway — also included data from both EO 12333 collection and Section 215 collection, both mixed in together. Importantly, data with one-end in foreign will be redundant, collected under both EO 12333 and 215. Indeed, a training program from 2011 trained analysts to re-run BRFISA queries that could be replicated under EO 12333 so they could be shared more permissively. That said, a footnote (see footnote 13) in phone dragnet orders that has mostly remained redacted appears to impose the BRFISA handling rules on any data comingled with it, so this may limit (or have imposed new more recent limits) on contact chaining between authorities.

As I noted, NSA shut down the automatic features on BRFISA data in 2009. But once data comes back in a query, it can be subjected to NSA’s “full range of analytical tradecraft,” as every phone dragnet order explains. Thus, while the majority of Americans who don’t come up in a query don’t get subjected to more intrusive analysis, if you’re 3 hops (now 2) from someone of interest, you can be — everything, indefinitely. I would expect that to include trolling all of NSA’s collected data to see if any of your other identifiable data comes up in interesting ways. That’s a ton of innocent people who get sucked into NSA’s maw and will continue to even after/if the phone dragnet moves to the providers.

DEA, International

As I said, the analogue to the program described by the USA Today, dubbed USTO, is not the Section 215 database, but instead the EO 12333 database (indeed, USAT describes that DEA included entirely foreign metadata in their database as well). The data in this program provided by domestic providers came under 21 USC 876 — basically the drug war equivalent of the Section 215 “tangible things” provision. An DEA declaration in the Shantia Hassanshahi case claims it only provides base metadata, but it doesn’t specify whether that includes or excludes location. As USAT describes (and would have to be the case for Hassanshahi to be busted for sanctions violations using it, not to mention FBI’s success at stalling of DOJ IG’s investigation into it), this database came to be used for other than counternarcotics purposes (note, this should have implications for EO 12333, which I’ll get back to). And, as USAT also described, like the NSA dragnet, the USTO also linked right into automatic analysis (and, I’m willing to bet good money, tracked multiple types of metadata). As USAT describes, DEA did far more queries of this database than of the Section 215 dragnet, but that’s not analogous; the proper comparison would be with NSA’s 12333 dragnet, and I would bet the numbers are at least comparable (if you can even count these automated chaining processes anymore). DEA says this database got shut down in 2013 and claims the data was purged. DEA also likely would like to sell you the Brooklyn Bridge real cheap.

DEA, Domestic

There’s also a domestic drug-specific dragnet, Hemisphere, that was first exposed by a NYT article. This is not actually a DEA database at all. Rather, it is a program under the drug czar that makes enhanced telecom data available for drug purposes, while the records appear to stay with the telecom.

This seems to have been evolving since 2007 (which may mark when telecoms stopped turning over domestic call records for a range of purposes). At one point, it pulled off multiple providers’ networks, but more recently it has pulled only off AT&T’s networks (which I suspect is increasingly what has happened with the Section 215 phone dragnet).

But the very important feature of Hemisphere — particularly as compared to its analogue, the Section 215 dragnet — is that the telecoms perform the same kind of analysis they would do for their own purposes. This includes using location data and matching burner phones (though this is surely one of the automated functions included in NSA’s EO 12333 dragnet and DEA’s USTO). Thus, by keeping the data at the telecoms, the government appears to be able to do more sophisticated kinds of analysis on domestic data, even if it does so by accessing fewer records.

That is surely the instructive motivation behind Obama’s decision to “let” NSA move data back to the telecoms. It’d like to achieve what it can under Hemisphere, but with data from all telecom providers rather than just AT&T.

CIA

At least as the NSA documents concerning ICREACH tell it, CIA and DEA jointly developed a sharing platform called PROTON that surely overlaps with USTO in significant ways. But PROTON appeared to reside with CIA (and FBI and NSA were late additions to the PROTON sharing). PROTON included CIA specific metadata (that is, not telecommunications metadata but rather metadata tracking their own HUMINT). But in 2006 (these things all started to change around that time), NSA made a bid to become the premiere partner here with ICREACH, supporting more types of metadata and sharing it with international partners.

So we don’t know what CIA’s own dragnet looks like, just that it has one, one not bound to just telecommunications.

In addition, CIA has a foreign intelligence equivalent of Hemisphere, where it pays AT&T to “voluntarily” hand over data that is at least one-end foreign (and masks the US side unless the record gets referred to FBI).

Finally, CIA can “upload or transfer some or all” of the metadata that it pulls off of raw PRISM data received under 702 into its other databases. While this has to be targeted off a foreign target, that surely includes a lot of US person data, and metadata including Internet based calls, photos, as well as emails. CIA does a lot of metadata queries for other entities (other IC agencies? foreign partners? who knows!), and they don’t count it, so they are clearly doing a lot of it.

FBI

As far as we know, FBI does not have a true “bulk” dragnet, sucking up all the phone or Internet records for the US or foreign switches. But it surely has fairly massive metadata repositories itself.

Until 2006, it did, however, have something almost identical to what we understand Hemisphere to be, all the major telecoms, sitting onsite, ready to do sophisticated analysis of numbers offered up on a post-it note, with legal process to follow (maybe) if anything nifty got turned over. Under this program, AT&T offered some bells and whistles, included “communities of interest” that included at least one hop. That all started to get moved offsite in 2006, when DOJ’s IG pointed out that it didn’t comply with the law, but all the telecoms originally contracted (AT&T and the companies that now comprise Verizon, at least), remained on contract to provide those services albeit offsite for a few years. In 2009, one of the telecoms (which is likely part or all of Verizon) pulled out, meaning it no longer has a contract to provide records in response to NSLs and other process in the form the FBI pays it to.

FBI also would have a database of the records it has collected using NSLs and subpoenas (I’ll go look up the name shortly), going back decades. Plus, FBI, like CIA, can “upload or transfer some or all” of the metadata that it pulls off of raw PRISM data received under 702. So FBI has its own bulky database, but all of the data in it should have come in in relatively intentional if not targeted fashion. What FBI does have should date back much longer than NSA’s Section 215 database (30 years for national security data) and, under the new Section 309 restrictions on EO 12333 data, even NSA’s larger dragnet. On top of that, AT&T still provides 7 bells and whistles that are secret and that go beyond a plain language definition of what they should turn over in response to an NSL under ECPA (which probably parallel what we see going on in Hemisphere). In its Section 215 report, PCLOB was quite clear that FBI almost always got the information that could have come out of the Section 215 dragnet via NSLs and its other authorities, so it seems to be doing quite well obtaining what it needs without collecting all the data everywhere, though there are abundant reasons to worry that the control functions in FBI’s bulky databases are craptastic compared to what NSA must follow.

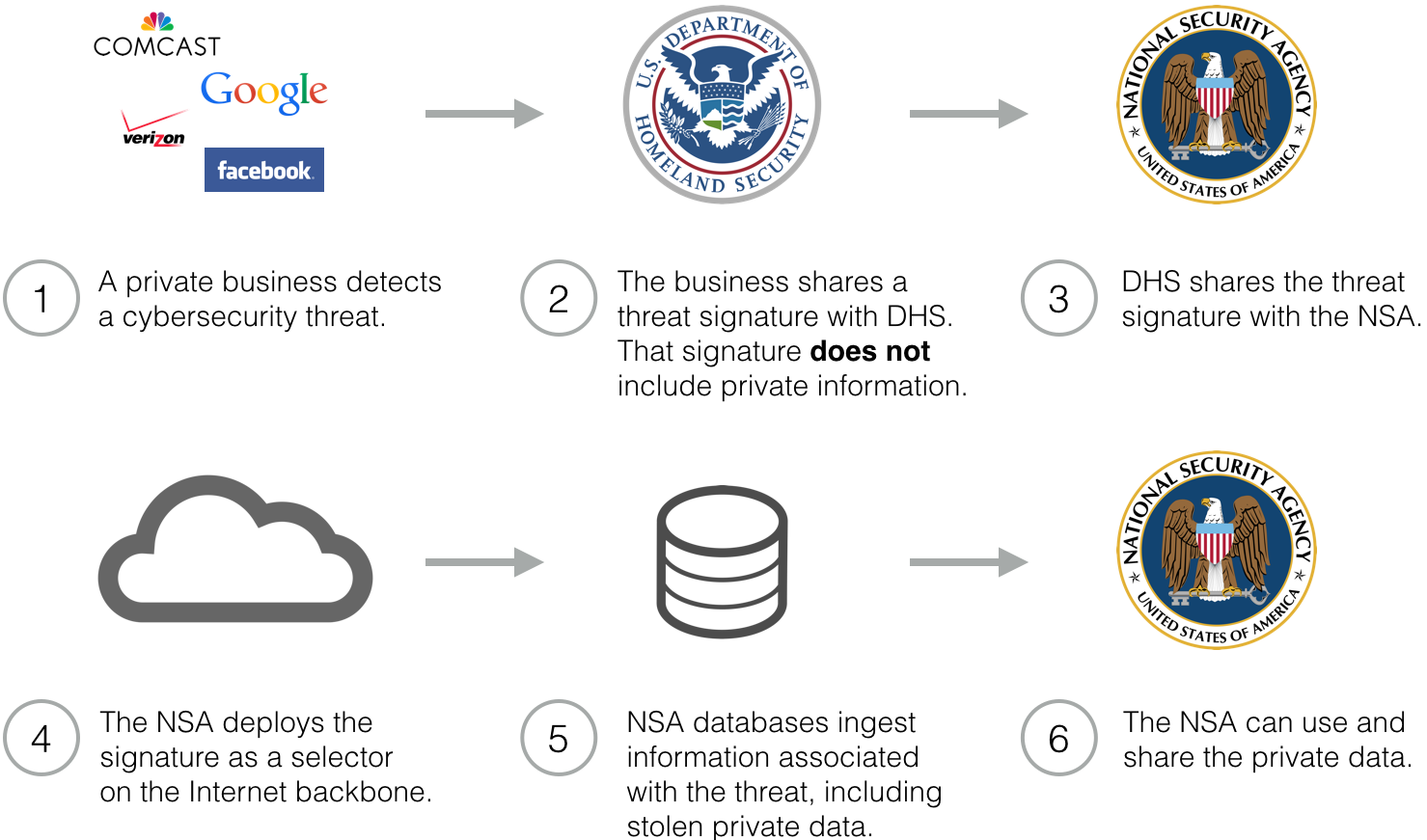

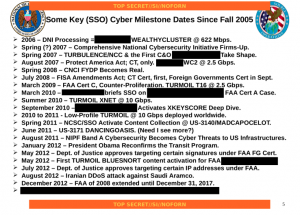

I’ve been puzzling over the list of “key SSO cyber milestone dates” released with the upstream 702 story the other day.

I’ve been puzzling over the list of “key SSO cyber milestone dates” released with the upstream 702 story the other day.