The Hack or Attack Debate: Answer Old Questions While Waiting to Learn Enough to Answer That One

As people in government, particularly members of Congress posturing for the cameras, start responding to the SolarWinds compromise, some have adopted a bellicose language unsupported by the facts, at least those that are public. Dick Durbin, for example, called it, “virtually a declaration of war.” That has led to some necessary pushback noting that as far as we know, this is an act of espionage, not sabotage. It’s the kind of thing we do as well without declaring war.

As usual, I substantially agree with Jack Goldsmith on these issues.

The lack of self-awareness in these and similar reactions to the Russia breach is astounding. The U.S. government has no principled basis to complain about the Russia hack, much less retaliate for it with military means, since the U.S. government hacks foreign government networks on a huge scale every day. Indeed, a military response to the Russian hack would violate international law. The United States does have options, but none are terribly attractive.

[snip]

The larger context here is that for many reasons—the Snowden revelations, the infamous digital attack on Iranian centrifuges (and other warlike uses of digital weapons), the U.S. “internet freedom” program (which subsidizes tools to circumvent constraints in authoritarian networks), Defend Forward, and more—the United States is widely viewed abroad as the most fearsome global cyber bully. From our adversaries’ perspective, the United States uses its prodigious digital tools, short of war, to achieve whatever advantage it can, and so adversaries feel justified in doing whatever they can as well, often with fewer scruples. We can tell ourselves that our digital exploits in foreign governmental systems serve good ends, and that our adversaries’ exploits in our systems do not, and often that is true. But this moral judgment, and the norms we push around it, have had no apparent influence in tamping down our adversaries’ harmful attacks on our networks—especially since the U.S. approach to norms has been to give up nothing that it wants to do in the digital realm, but at the same time to try to cajole, coerce, or shame our adversaries into not engaging in digital practices that harm the United States.

Goldsmith’s point about the Defend Forward approach adopted under Trump deserves particular focus given that, purportedly in the days since the compromise became known, Kash Patel is taking steps to split NSA and CyberCommand, something that would separate the Defend Forward effort from NSA.

Trump administration officials at the Pentagon late this week delivered to the Joint Chiefs of Staff a proposal to split up the leadership of the National Security Agency and U.S. Cyber Command. It is the latest push to dramatically reshape defense policy advanced by a handful of key political officials who were installed in acting roles in the Pentagon after Donald Trump lost his re-election bid.

A U.S. official confirmed on Saturday that Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Mark Milley — who along with Acting Defense Secretary Chris Miller must certify that the move meets certain standards laid out by Congress in 2016 — received the proposal in the last few days.

With Miller expected to sign off on the move, the fate of the proposal ultimately falls to Milley, who told Congress in 2019 that the dual-hat leadership structure was working and should be maintained.

As Reuters has reported, General Nakasone was pretty hubristic about NSA’s recent efforts to infiltrate our adversaries (Nakasone has, in unprecedented fashion, also chosen to officially confirm efforts CyberCom has made, which he must think has a deterrent effect that, it’s now clear, did not).

Speaking at a private dinner for tech security executives at the St. Regis Hotel in San Francisco in late February, America’s cyber defense chief boasted how well his organizations protect the country from spies.

U.S. teams were “understanding the adversary better than the adversary understands themselves,” said General Paul Nakasone, boss of the National Security Agency (NSA) and U.S. Cyber Command, according to a Reuters reporter present at the Feb. 26 dinner. His speech has not been previously reported.

Yet even as he spoke, hackers were embedding malicious code into the network of a Texas software company called SolarWinds Corp, according to a timeline published by Microsoft and more than a dozen government and corporate cyber researchers.

A little over three weeks after that dinner, the hackers began a sweeping intelligence operation that has penetrated the heart of America’s government and numerous corporations and other institutions around the world.

The failures of Defend Forward to identify this breach may raise questions about the dual hatting of NSA and CyberCommand, but there’s no good reason for these Trump flunkies to take any substantive steps in the last month of a Lame Duck period while it is serially refusing briefings to President Elect Biden’s team. All the more so because the more pressing issue, it seems, is giving CISA, the government’s defensive agency, more resources and authority.

More importantly, while it is too early to determine whether this goes beyond traditional espionage, there are questions that we can identify. For example, one detail that might suggest this was intended to do more than espionage is that the hackers stole FireEye’s Red Team tools. There are information gathering purposes for doing so, but they’re probably not important enough to risk blowing this entire operation, as happened. So we should at least consider whether the SolarWinds compromise aimed to pair intelligence (including that gathered from FERC, one of the agencies targeted) with the means to launch deniable sabotage on key critical infrastructure using FireEye’s tools.

Measurements of whether this is a hack or attack must also consider that the hackers are in a position where they could alter data. Consider what kind of mayhem Russia could do to our economy or world markets by altering data from Treasury. That is, the hackers are in a position where it’s possible, at least, to engage in sabotage without engaging in any kinetic act.

Finally, adopting the shorthand the industry uses for such things, there’s a bit of sloppiness about attribution. The working assumption this is APT 29, and the working reference is that APT 29 works for SVR, Russia’s foreign intelligence agency (even though when it was implicated in key hacks in 2016, it was assumed to work for FSB). I’ve been told by someone with more local knowledge that the relationship between these hackers and the intelligence agencies they work for may be more transactional. The people who’ve best understood the attack, including FireEye, think this may be a new “group.”

While intelligence officials and security experts generally agree Russia is responsible, and some believe it is the handiwork of Moscow’s foreign intelligence service, FireEye and Microsoft, as well as some government officials, believe the attack was perpetrated by a hacking group never seen before, one whose tools and techniques had been previously unknown.

Which brings me to a question we should be able to answer, one I’ve been harping on since the DNC leak first became public: what was the relationship between the hackers, APT 28 (the ones who stole files and shared the with WikiLeaks) and APT 29 (who then, and still, have been described as “just” spying). From the very first — and even in March 2017, after which discussions of the hack have become irredeemably politicized beyond recovery — there was some complexity surrounding the issue.

I have previously pointed to a conflict between what Crowdstrike claimed in its report on the DNC hack and what the FBI told FireEye. Crowdstrike basically said the two hacking groups didn’t coordinate at all (which Crowdstrike took as proof of sophistication). Whereas FireEye said they did coordinate (which it took as proof of sophistication and uniqueness of this hack). I understand the truth is closer to the latter. APT 28 largely operated on its own, but at times, when it hit a wall of sorts, it got help from APT 29 (though there may have been some back and forth before APT 29 did share).

When I said I understood the truth was closer to the latter — that there was some cooperated between APT 28 and 29, it was based on what a firsthand witness, who had been involved in defending a related target in 2016, told me. He said, in general, there was no cooperation between the two sets of hackers, but on a few occasions APT 29 seemed to assist APT 28. That’s unsurprising. The attack in 2016 was ambitious, years in planning, and Putin was personally involved. He would obviously have the ability to demand coordination for this operation, so intelligence collected by APT 29 may well have dictated choices made in where to throw GRU’s efforts.

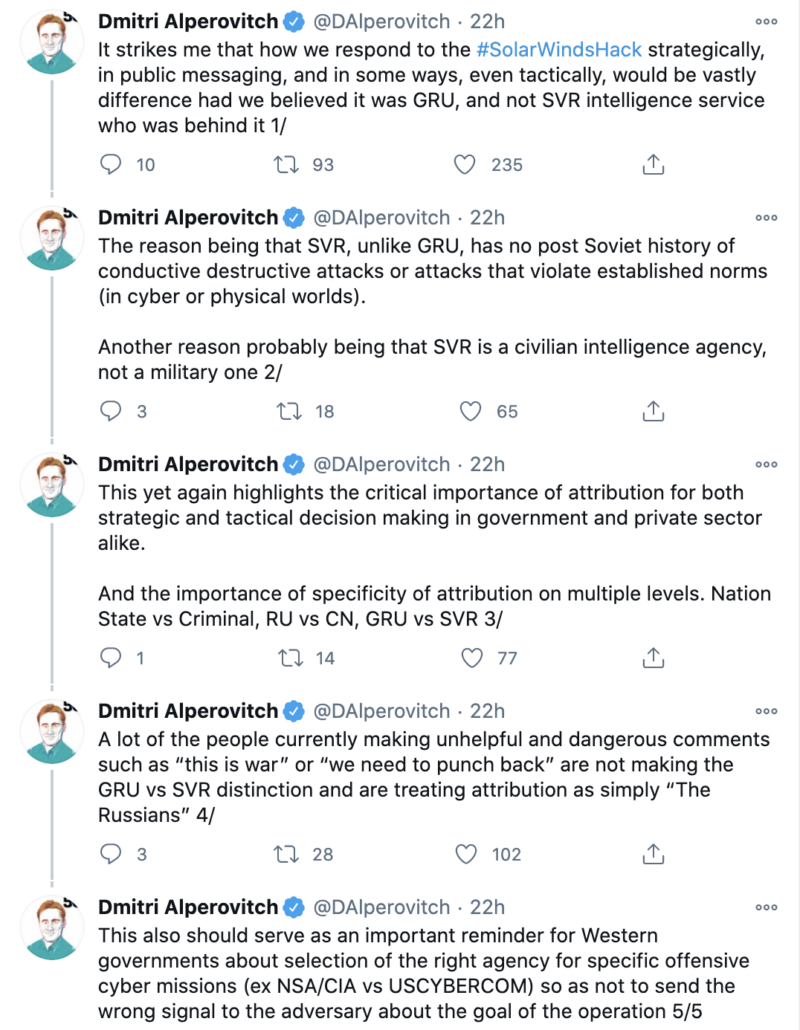

The point is important now, especially as people like CrowdStrike’s former CTO Dmitri Alperovitch recommends responses based on the assumption that this is SVR and therefore that dictates what Russia intends.

So we should assume this is espionage and therefore avoid escalating language for the moment. But having had our assess handed to us already, with a sophisticated campaign launched as we were busy looking for election hackers, it would be a big mistake IMO to rely on easy old categories to try to understand this.

Update: Corrected to reflect that Alperovitch is no longer with CrowdStrike.