Consider CISA a Six-Month Distraction from Shoring Up Government Security

Most outlets that commented on DHS’ response to Al Franken’s questions about CISA focused on their concerns about privacy.

The authorization to share cyber threat indicators and defensive measures with “any other entity or the Federal Government,” “notwithstanding any other provision of law” could sweep away important privacy protections, particularly the provisions in the Stored Communications Act limiting the disclosure of the content of electronic communications to the government by certain providers. (This concern is heightened by the expansive definitions of cyber threat indicators and defensive measures in the bill. Unlike the President’s proposal, the Senate bill includes “any other attribute of a cybersecurity threat” within its definition of cyber threat indicator and authorizes entities to employ defensive measures.)

[snip]

To require sharing in “real time” and “not subject to any delay [or] modification” raises concerns relating to operational analysis and privacy.

First, it is important for the NCCIC to be able to apply a privacy scrub to incoming data, to ensure that personally identifiable information unrelated to a cyber threat has not been included. If DHS distributes information that is not scrubbed for privacy concerns, DHS would fail to mitigate and in fact would contribute to the compromise of personally identifiable information by spreading it further. While DHS aims to conduct a privacy scrub quickly so that data can be shared in close to real time, the language as currently written would complicate efforts to do so. DHS needs to apply business rules, workflows and data labeling (potentially masking data depending on the receiver) to avoid this problem.

None of those outlets noted that DOJ’s Inspector General cited privacy concerns among the reasons why private sector partners are reluctant to share data with FBI.

So the limited privacy protections in CISA are actually a real problem with it — one changes in a manager’s amendment (the most significant being a limit on uses of that data to cyber crimes rather than a broad range of felonies currently in the bill) don’t entirely address.

But I think this part of DHS’ response is far more important to the immediate debate.

Finally the 90-day timeline for DHS’s deployment of a process and capability to receive cyber threat indicators is too ambitious, in light of the need to fully evaluate the requirements pertaining to that capability once legislation passes and build and deploy the technology. At a minimum, the timeframe should be doubled to 180 days.

DHS says the bill is overly optimistic about how quickly a new cybersharing infrastructure can be put in place. I’m sympathetic with their complaint, too. After all, if it takes NSA 6 months to set up an info-sharing infrastructure for the new phone dragnet created by USA Freedom Act, why do we think DHS can do the reverse in half the time?

Especially when you consider DHS’ concerns about the complexity added because CISA permits private sector entities to share with any of a number of government agencies.

Equally important, if cyber threat indicators are distributed amongst multiple agencies rather than initially provided through one entity, the complexity–for both government and businesses–and inefficiency of any information sharing program will markedly increase; developing a single, comprehensive picture of the range of cyber threats faced daily will become more difficult. This will limit the ability of DHS to connect the dots and proactively recognize emerging risks and help private and public organizations implement effective mitigations to reduce the likelihood of damaging incidents.

DHS recommends limiting the provision in the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act regarding authorization to share information, notwithstanding any other provision of law, to sharing through the DHS capability housed in the NCCIC.

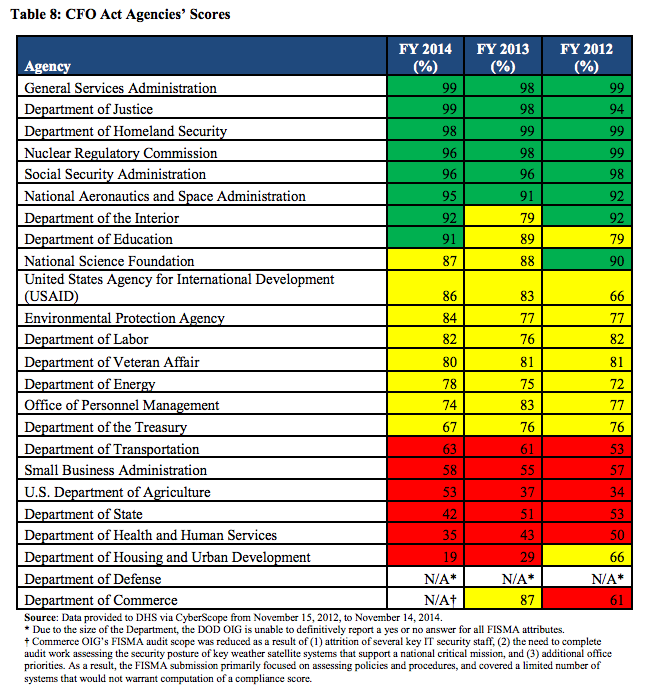

Admittedly, some of this might be attributed to bureaucratic turf wars — albeit turf wars that those who’d prefer DHS do a privacy scrub before FBI or NSA get the data ought to support. But DHS is also making a point about building complexity into a data sharing portal that recreates one that already exists that has less complexity (as well as some anonymizing and minimization that might be lost under the new system). That complexity is going to make the whole thing less secure, just as we’re coming to grips with how insecure government networks are. It’s not clear, at all, why a new portal needs to be created, one that is more complex and involves agencies like the Department of Energy — which is cybersprinting backwards on its own security — at the front end of that complexity, one that lacks some safeguards that are in the DHS’ current portal.

More importantly, that complexity, that recreation of something that already exists — that’s going to take six months of DHS’s time, when it should instead be focusing on shoring up government security in the wake of the OPM hack.

Until such time as Congress wants to give the agencies unlimited resources to focus on cyberdefense, it will face limited resources and with those limited resources some real choices about what should be the top priority. And while DHS didn’t say it, it sure seems to me that CISA would require reinventing some wheels, and making them more complex along the way, at a time when DHS (and everyone in government focused on cybersecurity) have better things to be doing.

Congress is already cranky that the Administration took a month two months to cybersprint middle distance run in the wake of the OPM hack. Why are they demanding DHS spend 6 more months recreating wheels before fixing core vulnerabilities?

![[photo: K2D2vaca via Flickr]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Chrysler_K2D2vaca-Flickr-300x218.jpg)