John Doe Ungagged: Nicholas Merrill Wins the Right to Reveal Contents of 11-Year Old National Security Letter

Nicholas Merrill, who first challenged a National Security Letter 11 years ago, has won the right to talk about what he was ordered to turn over to the FBI in 2004. A key holding from the decision is that private citizens — as distinct from government officials who have signed non-disclosure agreements — cannot be prevented from talking about stuff that the government, as a whole, has already released.

A private citizen should be able to disclose information that has already been publicly disclosed by any government agency — at least once the underlying investigation has concluded and there is no reason for the identities of the recipient and target to remain secret. Otherwise, it would lead to the result that citizens who have not received such an NSL request can speak about information that is publicly known (and acknowledged by other agencies), but the very individuals who have received such NSL requests and are thus best suited to inform public discussion on the topic could not. Such a result would lead to “unending secrecy of actions taken by government officials” if private citizens actually affected by publicly known law enforcement techniques could not discuss them.

The judge in the case, Victor Marrero, gave the government 90 days to appeal. If they don’t (?!?!), Merrill will finally be ungagged after 11 years of fighting.

As noted, the FBI served the NSL back in 2004, when Merrill ran a small Internet Service Provider. Merrill sued under the name John Doe. He twice won court rulings that the gag orders were unconstitutional. But it wasn’t until 2010 that he was allowed to ID himself as Doe, and it wasn’t until 2014 — a decade after receiving the NSL — that he was able to tell the person whose records the FBI wanted. Even then, even after Edward Snowden revealed the need for more transparency about these things, the government fought Merrill’s demand to disclose what he had been asked to turn over, which was included in an attachment to the NSL itself.

See this post and this post for background on Merrill’s renewed fight to disclose how much FBI has demanded under an NSL.

Marrero found that the government just didn’t have really good reasons to gag this information, especially given that substantially similar information had been given out by other government agencies, and especially since the government admits it is only trying to hide the information from future targets, not anyone tied to the investigation that precipitated the NSL over a decade ago.

For the reasons discussed below, the court finds that the Government has not satisfied its burden of demonstrating a “good reason” to expect that disclosure of the NSL Attachment in its entirety will risk an enumerated harm, pursuant to Sections 2709 and 3511.

[snip]

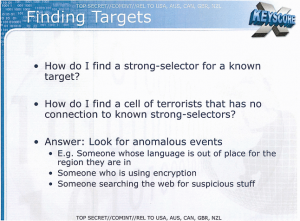

The Government argues that disclosure of the Attachment would reveal law enforcement techniques that the FBI has not acknowledged in the context of NSLs, would indicate the types of information the FBI deems important for investigative purposes, and could lead to potential targets of investigations changing their behavior to evade law enforcement detection. {See Gov’t Mem. at 6.) The Court agrees that such reasons could, in some circumstances, constitute “good” reasons for disclosure.

[snip]

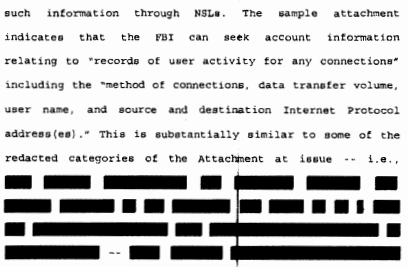

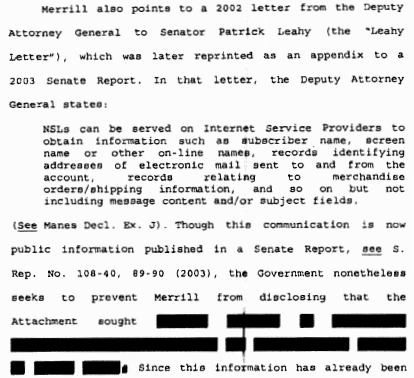

The Government’s justifications might constitute “good” reasons if the information contained in the Attachment that is still redacted were not, at least in substance even if not in the precise form, already disclosed by government divisions and agencies, and thus known to the public. Here, publicly-available government documents provide substantially similar information as that set forth in the Attactunent. For that reason, the Court is not persuaded that it matters that these other documents were not disclosed by the FBI itself rather than by other government agencies, and that they would hold significant weight for a potential target of a national security investigation in ascertaining whether the FBI would gather such information through an NSL. The documents referred to were prepared and published by various government divisions discussing the FBI’s authority to issue NSLs, the types of materials the FBI seeks, and how to draft NSL requests.

[snip]

Now, unlike earlier iterations of this litigation, the asserted Government interest in keeping the Attachment confidential is based solely on protecting law enforcement sensitive information that is relevant to future or potential national security investigations.

[snip]

[I]t strains credulity that future targets of other investigations would change their behavior in light of the currently-redacted information, when those targets (which, according to the Government, [redacted] see Perdue Deel. ¶ 56) have access to much of this same information from other government divisions and agencies.

Effectively, Marrero is arguing that since the government has asserted potential national security targets are good at putting 2 plus 2 together, and 2 and 2 are already in the public domain, any targets can already access the information in the attachment.

Marrero’s quotations from already released documents and the redactions from the attachment make it clear the government is trying to hide they were getting activity logs…

And the various identities tied to an account (which we know the government matches to better be able to map activity across multiple identities).

I’ll lay more of this out shortly — effectively, Marrero has already done the mosaic work for targets, even without the attachment (though I suspect what the government is really trying to prevent is release of a document defendants can point to to support discovery requests).

Ultimately, Marrero points to the absurd — and dangerous, for a democracy — position that would result if the government were able to suppress this already public information.

If the Court were to find instead that the Government has met its burden of showing a good reason for nondisclosure here, could Merrillever overcome such a showing? Under the Government’s reasoning, the Court sees only two such hypothetical circumstances in which Merrill could prevail: a world in which no threat of terrorism exists, or a world in which the FBI, acting on its own accord and its own time, decides to disclose the contents of the Attachment. Such a result implicates serious issues, both with respect to the First Amendment and accountability of the government to the people.

Especially at a time when the President claims to want to reverse the practice of forever gags on NSLs, Marrero finds such a stance untenable.

Let’s see whether the government doubles down on secrecy.