Facebook Claims Just .1% of Election Related Sharing Was Information Operations

In a fascinating report on the use of the social media platform for Information Operations released yesterday, Facebook make a startling claim. Less than .1% of what got shared during the election was shared by accounts set up to engage in malicious propaganda.

Concurrently, a separate set of malicious actors engaged in false amplification using inauthentic Facebook accounts to push narratives and themes that reinforced or expanded on some of the topics exposed from stolen data. Facebook conducted research into overall civic engagement during this time on the platform, and determined that the reach of the content shared by false amplifiers was marginal compared to the overall volume of civic content shared during the US election.12

In short, while we acknowledge the ongoing challenge of monitoring and guarding against information operations, the reach of known operations during the US election of 2016 was statistically very small compared to overall engagement on political issues.

12 To estimate magnitude, we compiled a cross functional team of engineers, analysts, and data scientists to examine posts that were classified as related to civic engagement between September and December 2016. We compared that data with data derived from the behavior of accounts we believe to be related to Information Operations. The reach of the content spread by these accounts was less than one-tenth of a percent of the total reach of civic content on Facebook.

That may seem like a totally bogus number — and it may well be! But to assess it, understand what they’re measuring.

That’s one of the laudable aspects of the report: it tries to break down the various parts of the process, distinguishing things like “disinformation” — inaccurate information spread intentionally — from “misinformation” — inaccurate information spread without malicious intent.

Information (or Influence) Operations – Actions taken by governments or organized non-state actors to distort domestic or foreign political sentiment, most frequently to achieve a strategic and/or geopolitical outcome. These operations can use a combination of methods, such as false news, disinformation, or networks of fake accounts (false amplifiers) aimed at manipulating public opinion.

False News– News articles that purport to be factual, but which contain intentional misstatements of fact with the intention to arouse passions, attract viewership, or deceive.

False Amplifiers – Coordinated activity by inauthentic accounts with the intent of manipulating political discussion (e.g., by discouraging specific parties from participating in discussion, or amplifying sensationalistic voices over others).

Disinformation – Inaccurate or manipulated information/content that is spread intentionally. This can include false news, or it can involve more subtle methods, such as false flag operations, feeding inaccurate quotes or stories to innocent intermediaries, or knowingly amplifying biased or misleading information. Disinformation is distinct from misinformation, which is the inadvertent or unintentional spread of inaccurate information without malicious intent.

Having thus defined those terms, Facebook distinguishes further between false news sent with malicious intent from that sent for other purposes — such as to make money. In this passage, Facebook also acknowledges the important detail for it: false news doesn’t work without amplification.

Intent: The purveyors of false news can be motivated by financial incentives, individual political motivations, attracting clicks, or all the above. False news can be shared with or without malicious intent. Information operations, however, are primarily motivated by political objectives and not financial benefit.

Medium: False news is primarily a phenomenon related to online news stories that purport to come from legitimate outlets. Information operations, however, often involve the broader information ecosystem, including old and new media.

Amplification: On its own, false news exists in a vacuum. With deliberately coordinated amplification through social networks, however, it can transform into information operations

So the stat above — the amazingly low .1% — is just a measure of the amplification of stories by Facebook accounts created for the purpose of maliciously amplifying certain fake stories; it doesn’t count the amplification of fake stories by people who believe them or who aren’t formally engaged in an information operation. Indeed, the report notes that after an entity amplifies something falsely, “organic proliferation of the messaging and data through authentic peer groups and networks [is] inevitable.” The .1% doesn’t count Trump’s amplification of stories (or of his followers).

Furthermore, the passage states it is measuring accounts that “reinforced or expanded on some of the topics exposed from stolen data,” which would seem to limit which fake stories it tracked, including things like PizzaGate (which derived in part from a Podesta email) but not the fake claim that the Pope endorsed Trump (though later on the report says it identifies false amplifiers by behavior, not by content).

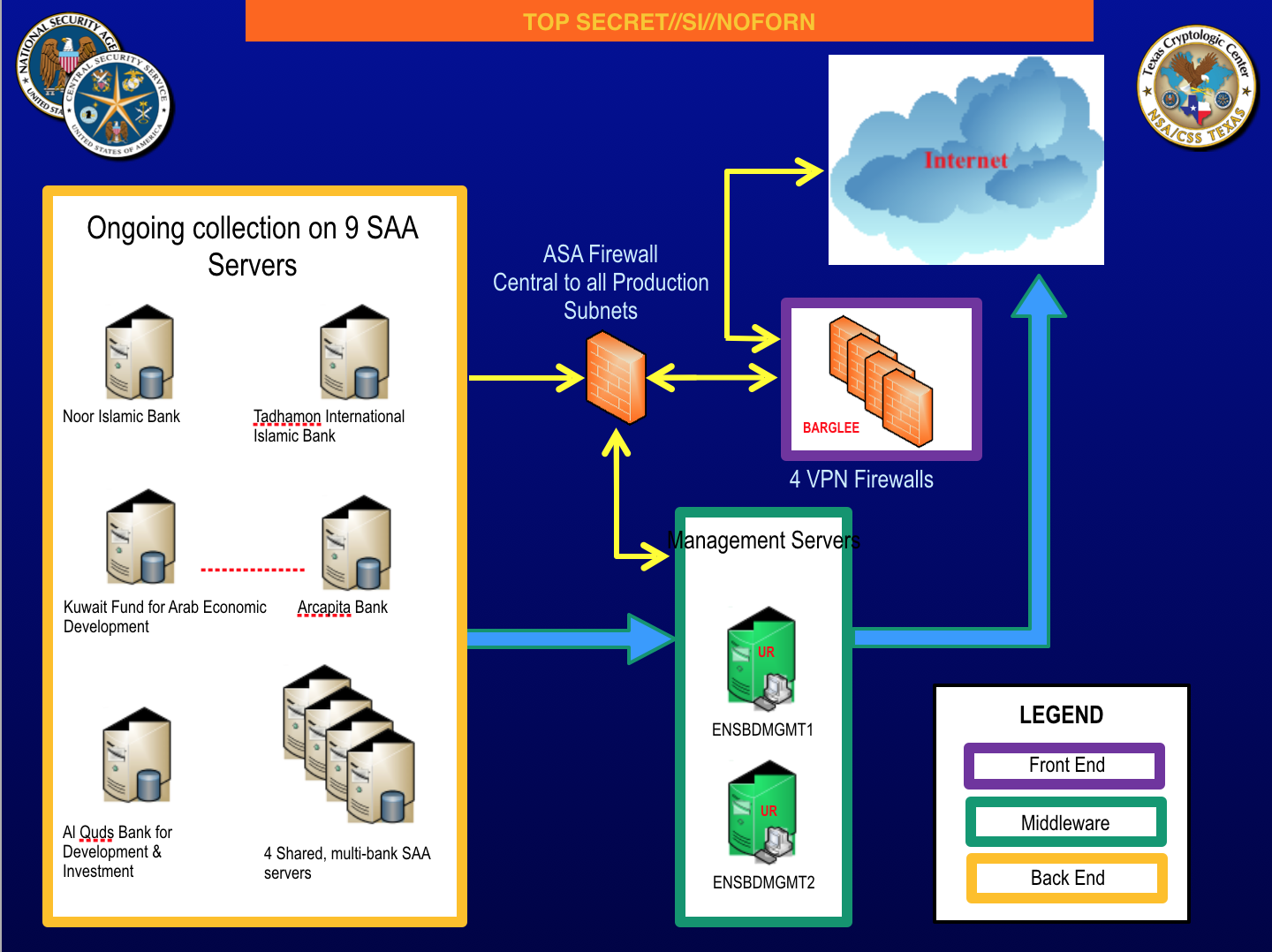

The entire claim raises questions about how Facebook identifies which are the false amplifiers and which are the accounts “authentically” sharing false news. In a passage boasting of how it has already suspended 30,000 fake accounts in the context of the French election, the report includes an image that suggests part of what it does to identify the fake accounts is identifying clusters of like activity.

But in the US election section, the report includes a coy passage stating that it cannot definitively attribute who sponsored the false amplification, even while it states that its data does not contradict the Intelligence Community’s attribution of the effort to Russian intelligence.

Facebook is not in a position to make definitive attribution to the actors sponsoring this activity. It is important to emphasize that this example case comprises only a subset of overall activities tracked and addressed by our organization during this time period; however our data does not contradict the attribution provided by the U.S. Director of National Intelligence in the report dated January 6, 2017.

That presents the possibility (one that is quite likely) that Facebook has far more specific forensic data on the .1% of accounts it deems malicious amplifiers that it coyly suggests it knows to be Russian intelligence. Note, too, that the report is quite clear that this is human-driven activity, not bot-driven.

So the .1% may be a self-serving number, based on a definition drawn so narrowly as to be able to claim that Russian spies spreading propaganda make up only a tiny percentage of activity within what it portrays as the greater vibrant civic world of Facebook.

Alternately, it’s a statement of just how powerful Facebook’s network effect is, such that a very small group of Russian spies working on Facebook can have an outsized influence.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)