NB: Before reading:

1) Check the byline — this is NotMarcy;

2) Some of this content is speculative;

3) This is a minority report; I’m not on the same paragraph and perhaps not the same page with Marcy.

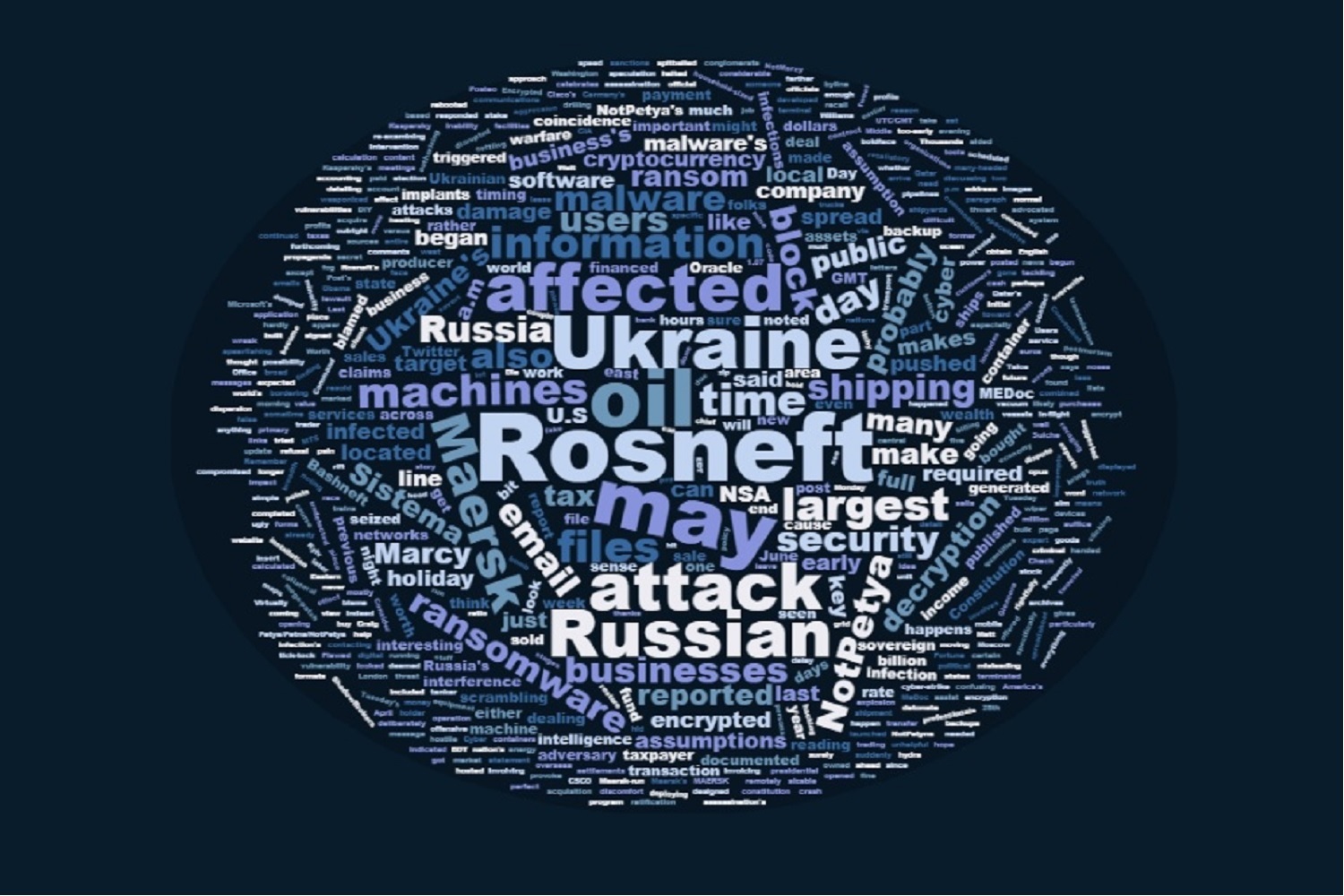

Tuesday’s ‘Petya/Petna/NotPetya’ malware attacks generated a lot of misleading information and rapid assumptions. Some of the fog can be rightfully blamed on the speed and breadth of infection. Some of it can also be blamed on the combined effect of information security professionals discussing in-flight attacks in full view of the public who make too many assumptions.

There’s also the possibility that some of the confusing information may have been deliberately generated to thwart too-early intervention. If this isn’t criminal hacking but cyber warfare, propaganda should be expected as in all other forms of warfare. Flawed assumptions, too, can be weaponized.

A key assumption worth re-examining is that Ukraine was NotPetya’s primary target rather than collateral damage.

After the malware completed its installation and rebooted an infected machine, a message indicated files had been encrypted and payment could be offered for decryption.

Thousands of dollars were paid $300 at a time in cryptocurrency but a decryption key wouldn’t be forthcoming. Users who tried to pay the ransom found the contact email address hosted by Posteo.net had been terminated. The email service company was unhelpful bordering on outright hostile in its refusal to assist users contacting the email account holder. It looked like a ransom scam gone very wrong.

As Marcy noted in her earlier post on NotPetyna, information security expert Matt Suiche posted that NotPetya was a wiper and not ransomware. The inability of affected users to obtain decryption code suddenly made perfect sense. ‘Encrypted’ files are never going to be opened again.

It’s important to think about the affected persons and organizations and how they likely responded to the infection. If they didn’t already have a policy in place for dealing with ransomware, they may have had impromptu meetings about their approach; they had to buy cryptocurrency, which may have required a crash DIY course in how to acquire it and how to make a payment — scrambling under the assumption they were dealing with ransomware.

It all began sometime after 10:30 UTC/GMT — 11:30 a.m. London (BDT), 1:30 p.m. Kyiv and Moscow local time, even later in points across Russia farther east.

(And 4:30 a.m. EDT — well ahead of the U.S. stock market, early enough for certain morning Twitter users to tweet about the attack before America’s work day began.)

The world’s largest shipping line, Maersk, and Russia’s largest taxpayer and oil producer Rosneft tweeted about the attack less than two hours after it began.

By the end of the normal work day in Ukraine time, staff would only have just begun to deal with the ugly truth that the ransom may have been handed off and no decryption key was coming.

As Marcy noted, June 28th is a public holiday in Ukraine — Constitution Day. I hope IT folks there didn’t have a full backup scheduled to run going into the holiday evening — one that might overwrite a previous full backup.

The infection’s spread rate suggested early on that email was not the only means of transmission, if it had been spread at all by spearfishing. But many information security folks advocated not opening any links in email. A false sense of security may have aided the malware’s dispersion; users may have thought, “I’m not clicking on anything, I can’t get it!” while their local area network was being compromised.

And then it hit them. While affected users sat at their machines reading fake messages displayed by the malware, scrambling to get cryptocurrency for the ransom, NotPetya continued to encrypt files under their noses and spread across business’s local area networks. Here’s where Microsoft’s postmortem is particularly interesting; it not only gives a tick-tock of the malware’s attack on a system, but it lists the file formats encrypted.

Virtually everything a business would use day to day was encrypted, from Office files to maps, website files to emails, zip archives and backups.

Oh, and Oracle files. Remember Oracle pushed a 299 vulnerability mega-patch on April 19, days after ShadowBrokers dumped some NSA tools? Convenient, that; these vulnerabilities were no longer a line of attack except through file encryption.

While information security experts have done a fine job tackling a many-headed hydra ravaging businesses, they made some rather broad assumptions about the reason for the attack. Kaspersky concluded the target was Ukraine since ~60% of infected devices were located there though 30% were located in Russia. But the malware’s aim may not have been the machines or even the businesses affected in Ukraine.

What did those businesses do? What they did required tax application software MEDoc. If the taxes to be calculated were based on business’s profits — (how much did they make) X (tax rate) — they hardly needed tax software. A simple spreadsheet would suffice, or the calculation would be built into accounting software.

No, the businesses affected by the malware pushed at 10:30 GMT via MEDoc update would be those which sold goods or services frequently, on which sales tax would have been required for each transaction.

What happens when a business’s sales can’t be documented? What happens when their purchases can’t be documented, either?

Which brings me to the affected Russian businesses, specifically Rosneft. There’s not much news published in English detailing the impact on Rosneft; we’ve only got Kaspersky’s word that 30% of infections affected Russian machines.

But if Rosneft is the largest public oil company in the world, Russia’s largest taxpayer as Rosneft says on their Twitter profile, it may not take very many infections to wreak considerable damage on the Russian economy. Consider the ratio of one machine invoicing the shipment of entire ocean tanker of oil versus many machines billing heating oil in household-sized quantities.

And if Rosneft oil was bought by Ukraine and resold to the EU, Ukraine’s infected machines would cause a delay of settlements to Russia especially when Rosneft must restore its own machines to make claims on Ukrainian customers.

The other interesting detail in this malware story is that the largest container line in the world, Maersk, was also affected. You may have seen shipping containers on trucks, trains, in shipyards and on ships marked in bold block letters, MAERSK. What you probably haven’t seen is Maersk’s energy transport business.

This includes shipping oil.

It’s not Ukraine’s oil Maersk ships; most of what Ukraine sells is through pipelines running from Russia in the east and mostly toward EU nations in the west.

It’s Russian oil, probably Rosneft’s, shipping overseas. If it’s not in Maersk container vessels, it may be moving through Maersk-run terminal facilities. And if Maersk has no idea what is shipping, where it’s located, when it will arrive, it will have a difficult time settling up with Rosneft.

Maersk also does oil drilling — it’s probably not Ukraine to whom Maersk may lease equipment or contract its services.

Give the potential damage to Russia’s financial interests, it seems odd that Ukraine is perceived as the primary target.

NotPetya’s attack didn’t happen in a vacuum, either.

A report in Germany’s Die Welt reported the assassination of Ukraine’s chief of intelligence by car bomb. The explosion happened about the same time that Ukraine’s central bank reported it had been affected by NotPetya — probably a couple hours after 10:30 a.m. GMT.

On Monday, privately-owned Russian conglomerate Sistema had a sizable chunk of assets “arrested” — not seized, but halted from sale or trading — due to a dispute with Rosneft over $2.8 billion dollars. Rosneft claims Sistema owes it money from the acquisition of oil producer Bashneft, owned by Sistema until 2014. Some of the assets seized included part of mobile communications company MTS. It’s likely this court case Rosneft referred to in its first tweet related to NotPetya.

The assassination’s timing makes the cyber attack look more like NotPetya was a Russian offensive, but why would Russia damage its largest sources of income and mess with its cash flow? The lawsuit against Sistema makes Rosneft appear itchy for income — Bashneft had been sold to the state in 2014, then Rosneft bought it from the state last year. Does Rosneft need this cash after the sale (or transfer) of a 19.5% stake worth $10.2 billion last year?

Worth noting here that Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund financed the bulk of the deal; commodities trader Glencore only financed 300 million euros of this transaction. How does the rift between other Middle Eastern oil states and Qatar affect the value of its sovereign wealth fund?

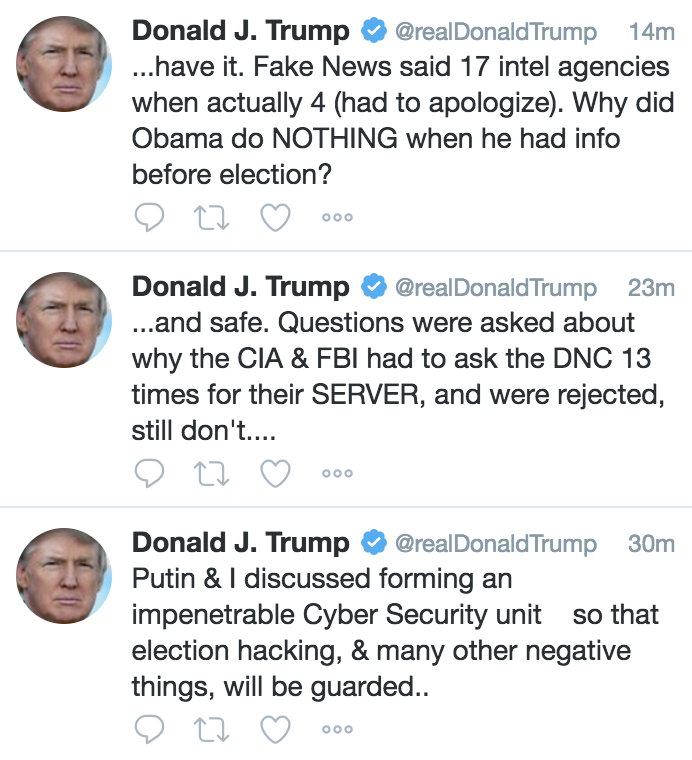

In her previous post, Marcy spitballed about digital sanctions — would they look like NotPetya? I think so. I can’t help recall this bit at the end of the Washington Post’s opus on Russian election interference published last week on June 23:

But Obama also signed the secret finding, officials said, authorizing a new covert program involving the NSA, CIA and U.S. Cyber Command.

[…]

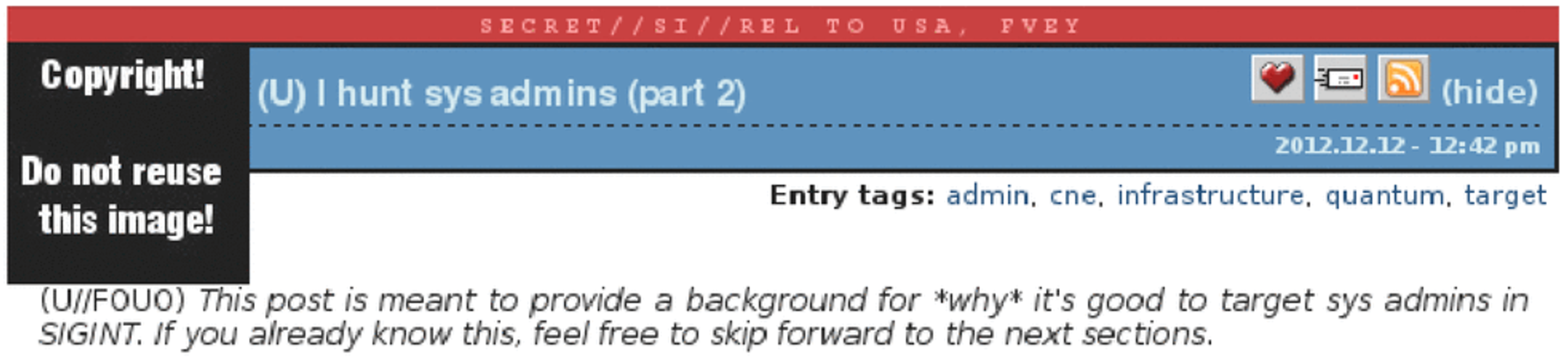

The cyber operation is still in its early stages and involves deploying “implants” in Russian networks deemed “important to the adversary and that would cause them pain and discomfort if they were disrupted,” a former U.S. official said.

The implants were developed by the NSA and designed so that they could be triggered remotely as part of retaliatory cyber-strike in the face of Russian aggression, whether an attack on a power grid or interference in a future presidential race.

I’m sure it’s just a coincidence that NotPetya launched Tuesday this week. This bit reported in Fortune is surely a coincidence, too:

The timing and initial target of the attack, MeDoc, is sure to provoke speculation that an adversary of Ukraine might be to blame. The ransomware hid undetected for five days before being triggered a day before a public Ukrainian holiday that celebrates the nation’s ratification of a new constitution in 1996.

“Last night in Ukraine, the night before Constitution Day, someone pushed the detonate button,” said Craig Williams, head of Cisco’s (CSCO, +1.07%) Talos threat intelligence unit. “That makes this more of a political statement than just a piece of ransomware.” [boldface mine]

Indeed.

Two more things before this post wraps: did anybody notice there has been little discussion about attribution due to characters, keyboards, language construction in NotPetya’s code? Are hackers getting better at producing code without tell-tale hints?

Did the previous attacks based on tools released by the Shadow Brokers have secondary — possibly even primary — purposes apart from disruption and extortion? Were they intended to inoculate enterprise and individual users before a destructive weapon like NotPetya was released? Were there other purposes not obvious to information security professionals?