What Lies Beneath the Gates

[NB: Note the byline; this post is speculative. /~Rayne]

It’s amazing what a simple internet search can reveal. Take, for instance, a search using the rather innocuous parameters, [“rick gates” iii “press release”].

A little scrolling and presto — some interesting things surface.

Did you know that Rick Gates had served on the board of ID Watchdog, a “consumer-facing identity theft protection and resolution services” firm for use in safeguarding personal credit? But that’s not the entire story; take a look at this timeline:

2010 — Gates, along with his business partner Paul Manafort, worked as an unregistered agent for Victor Yanukovych (who would take office as Ukraine’s president in 2010) and Yanukovych’s political parties. Gates and Manafort represented Yanukovych from at least 2006 through 2015, laundering Yanukovych’s payments through scores of U.S. and foreign entities and bank accounts, using foreign nominee companies and bank accounts created/opened by them and their accomplices in nominee names and in various foreign countries (see DOJ’s indictment dated 27-OCT-2017).

19-APR-2011 — Gates joined the board of publicly-listed credit monitoring firm ID Watchdog. Gates bio from the press release:

Mr. Gates has over 15 years of international political, finance and business development experience working for multinational firms. Currently, he is the managing partner of Pericles LP, a private equity fund, that focuses on technology, infrastructure, and real estate targets. Much of his work focuses on investment, business development and deal structures in Europe.

Mr. Gates has worked on several US presidential campaigns and has participated in many international political campaigns in Europe and Africa. Mr. Gates graduated with a M.A. in Public Policy from George Washington University and a B.A. in Government from The College of William & Mary. He also completed the Executive Management Programme in Brussels and London.

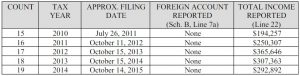

26-JUL-2011 — 2010 tax filing (assume Gates filed his taxes on/about this time in the absence of confirmation by image of tax return); a fraudulent tax return was filed.

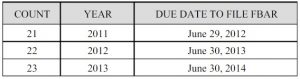

11-OCT-2012 through 14-OCT-2015 — Gates under-reported his income, filing fraudulent tax returns during this period which did not reflect full amount of payments from Yanukovych and parties. Gates also did not file Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR) reports disclosing offshore bank accounts from which cash was wired after being laundered through numerous shell businesses.

21-JUN-2016 — When Paul Manafort was elevated by Donald Trump to campaign chair after firing Corey Lewandowski, Gates worked as Manafort’s deputy. He would remain deputy after Manafort resigned on August 19.

09-NOV-2016 — Gates stepped down from his role at ID Watchdog, a day after the 2016 presidential election. He then became deputy chairman of the inaugural committee.

??-DEC-2016 — A security researcher notified credit reporting company Equifax that an employee portal was open to the internet and vulnerable.

07-MAR-2017 — A patch was issued for the Apache Struts (CVE-2017-5638) vulnerability.

??-MAR-2017 — Equifax was hacked for the first known time; it contacted Mandiant for assistance. It did not notify the government or consumers.

…the company said it experienced a security incident involving a payroll-related service during the 2016 tax season earlier this year. Equifax said the incident was reported to customers, affected individuals and regulators.

??-JUN-2017 — Equifax closed the vulnerable employee portal

16-JUN-2017 — ID Watchdog announced it had agreed to be acquired by Equifax.

13-MAY/30-JUL-2017 — From Equifax’s press release dated September 15:

Based on the company’s investigation, Equifax believes the unauthorized accesses to certain files containing personal information occurred from May 13 through July 30, 2017.

29-JUL-2017 — Date which Equifax’s CEO said a breach was first noticed.

01/02-AUG-2017 — Four Equifax executives who sold a combined $2 million in company stock over these two days claimed they did not know about the breach at the time they traded their shares.

02-AUG-2017 — Equifax contacted Mandiant to conduct a forensic investigation into the breaches. The fourth of four Equifax executives sold a portion of his company stock on the same day.

10-AUG-2017 — Equifax announced it had acquired ID Watchdog.

07-SEP-2017 — Equifax notified the public that it has been breached and 145.5 million consumers’ credit data has been exposed.

18-SEP-2017 — Equifax’s earlier breach in March was made public.

27-SEP-2017 — Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s then-Director Richard Cordray said regulators would be embedded within credit reporting companies to prevent future breaches of consumers’ data.

15-OCT-2017 — About this time, local news reported Gates was still working for Tom Barrack, CEO of Colony Capital and a member of the Presidential Council of Economic Advisers, prior to the indictment.

27-OCT-2017 — Gates was indicted for the first time.

15-NOV-2017 — Cordray stepped down as CFPB’s director.

25-NOV-2017 — Trump named Office of Budget and Management’s director Mick Mulvaney to succeed Cordray, to hold two offices concurrently.

18-JAN-2018 — Mulvaney allotted zero dollars for CFPB in the federal budget.

05-FEB-2018 — Mulvaney “pulled back from a full-scale probe” into Equifax’s breach.

This chain of events raises so many questions.

— Why Gates? Of all the people a public-listed company like ID Watchdog could pick, why this particular person with weak credentials in technology, let alone identity management or credit monitoring? Does Gates have a special relationship to ID Watchdog in some way?

— As a board member, what kind of access did Gates have to ID Watchdog’s systems? Did ID Watchdog have any ties or links to Equifax before the breaches?

— Did ID Watchdog provide any services to Gates — and possibly his partner, Paul Manafort — related to identity validation and monitoring? Did Gates acquire his second passport while serving on ID Watchdog’s board? What of his partner Manafort, who had at least 10 passports and possibly more identities?

— If ID Watchdog provided services to Gates, did any of Gates’ many bank accounts ever trigger alerts?

Gates “frequently changed banks and opened and closed bank accounts,” prosecutors said. In all, Gates opened 55 accounts with 13 financial institutions, the prosecutors’ court filing said. Some of his bank accounts were in England and Cyprus, where he held more than $10 million from 2010 to 2013.

— Doesn’t it seem odd Gates would serve on the board of an identity-monitoring firm located in Denver, CO while he was working frequently on lobbying-related contracts overseas and on the Trump campaign? Was he compensated by ID Watchdog and was this income reported accurately on tax filings?

— Did Equifax begin acquisition negotiations with ID Watchdog before or after Gates’ departure from the board? If before, did Gates play any role in the negotiations? Or does the timing of the acquisition simply look bad because of the breaches?

— Did Mick Mulvaney pull back on the CFPB’s investigation and oversight measures into Equifax as well as the other credit reporting bureaus to prevent any review of Trump campaign or administration members’ relationships with Equifax, or their data reported by Equifax and ID Watchdog? Did Mulvaney suppress the Equifax investigation and starve CFPB because he’s a misogynist ass and just wants to be a dick to Senator Elizabeth Warren? Or did Mulvaney merely toss ethics in his handling of CFPB including the Equifax investigation as payback for campaign contributors when he represented South Carolina as a congressman?

Perhaps it’s simply an interesting coincidence that a former Trump campaign team member who has been charged with multiple counts of bank and tax fraud, just happened to sit on ID Watchdog’s board of directors while he committed aforementioned fraud.

Maybe it’s just a weird quirk of fate that Equifax bought ID Watchdog around the same time it was being hacked a second time, potentially exposing Rick Gates’ credit records (and Paul Manafort’s) along with those of +145.5 million other consumers.

But it seems a massive stretch for us not to look a little further when Trump’s OMB director commits the CFPB to a slow death by budgetary starvation before icing the Equifax investigation and ID Watchdog’s role along with it.