What Seems to be Going on with MalwareTech’s New Charges

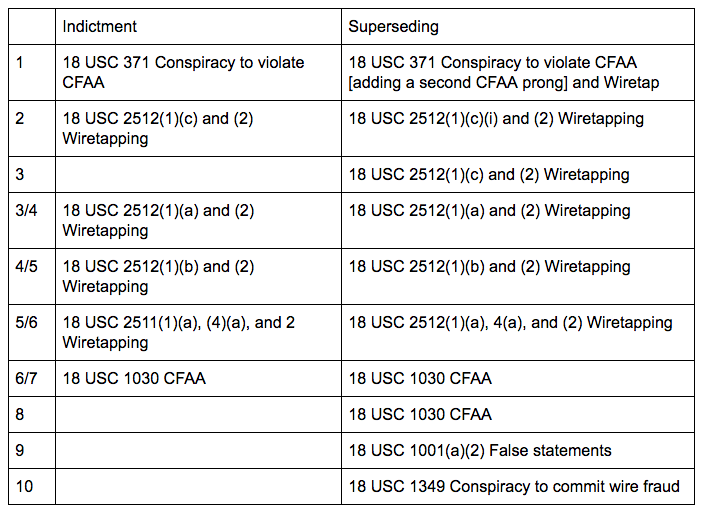

When I wrote this post on the superseding indictment against Marcus Hutchins (MalwareTech) I deferred assessment of the new charges — a differently charged CFAA, a wire fraud, and a false statements charge — until the lawyers weighed in. Last night, the two sides submitted a status report on the superseding indictment, and it’s clear that the government has fixed some glaring problems with its case. (Along the way the defense has argued they need to tweak all but one of the motions they had fully briefed, adding two months to this process, on top of the extra charges.)

By my read, the government has taken a detrimental ruling — that Hutchins will learn of the informant, Randy’s, identity at least a month before trial, if not before, as well as the fact that Hutchins did not, maybe could not, have admitted what they wanted to in his original interrogation but did admit to some other things, and used those setbacks to fix a number of problems with their case.

By my read (not a lawyer, not a judge, looking at just scraps of evidence), the original indictment against Hutchins was drawn up sloppily only as a means to detain him in this country and quickly — the government believed, because this is how things happen in the U S of A — get him to agree to inform on VinnyK and other online criminals. Indeed, fragments of the original interrogation now make it clear that was the intent.

Chartier: I mean, you know, Marcus, I’ll be honest with you. You’re in a fair bit of trouble.

Hutchins: Mmm-hmm.

Chartier: So I think it’s important that you try to give us the best picture, and if you tell me you haven’t talked to these guys for months, you know, you can’t really help yourself out of this hole. Does that make sense?

Hutchins: Yeah.

Chartier: Now, I’m not trying to tell you to do something you’re not doing, but I know you’re more active than you’re letting on, too. Okay?

Hutchins: I’m really not. I have ceased all criminal activity involving

Chartier: Yeah, but you still have access and information about these guys.

Hutchins: What do you mean? Like, give me a name and I’ll tell you what I know about that.

Chartier: All right, why don’t you start out with this list of nics.

As a result of that sloppiness, the government had just thrown a bunch of crimes — CFAA and wiretapping — into the indictment, with the assumption that it’d be enough to turn the guy who stopped WannaCry into the US government’s latest informant.

While there are no guarantees in criminal cases, I think the defense’s arguments that the government had no proof Hutchins intended to damage the requisite 10 computers in Wisconsin, nor that he had intended to install a device to wiretap, were sound. Indeed, this superseding indictment is largely tacit admission that those arguments may well succeed and blow their original case up. Moreover, I suspect there is and will remain (until this thing goes to trial, if it does) a dispute about how much code someone has to contribute to a piece of malware to be considered its author.

But as I said, now that the government is facing going to trial with their informant, Randy, fully exposed, they’ve turned that into a way to revamp the alleged crimes against Hutchins such that they might be sustainable. That’s because — as I pointed out here — while VinnyK is accused of selling malware, Randy has already told the FBI that he used it, and used it to engage in financial crimes.

- VinnyK (Individual A), a guy who sold a UPAS kit on July 3, 2012, days after Hutchins turned 18, and then on June 11, 2015, sold Kronos, a piece of malware with no known US victims. Altogether VinnyK made $3,500 for the two sales of malware alleged in this indictment. When this whole thing started, the government charged Hutchins mostly if not entirely to coerce him to provide information on VinnyK (information which he said in a chat in the government’s possession he doesn’t have). He’s the guy they’re supposed to be after, but now they’re after Hutchins exclusively.

- “Randy” (Individual B), an actual criminal “involved in the various cyber-based criminal enterprises including the unauthorized access of point-of-sale systems and the unauthorized access of ATMs.” At some point, in an attempt to limit or avoid his own criminal exposure, Randy implicated Hutchins.

With that in mind, consider the two new main charges the government has added, and added to the conspiracy, in what I imagine is a bid to sustain the prosecution if the earlier problems with the indictment get parts of the rest of it thrown out. In addition to charging Hutchins with the part of CFAA that makes it a crime to attempt to damage 10 or more protected computers, the government is now charging him with the part of CFAA that makes it a crime to intentionally access a computer to obtain information for the purpose of private financial gain. That is, they’ve added the part of CFAA that makes it a crime to profit from stealing information. They’ve also charged Hutchins with wire fraud for attempting to obtain money by false and fraudulent pretenses. (The defense now agrees the government has venue in EDWI, which I suspect has to do with both the focus on advertising here as opposed to operation of code, as well as the claim that Hutchins’ alleged lies thwarted an investigation in the district.)

The first of these is easy to understand. Even in the fragments of Hutchins’ interrogation publicly available, he admitted to selling code.

Chartier: So you haven’t had any other involvement in any other pieces of malware that are out or have been out?

Hutchins: Only the form-grabber and the bot.

Chartier: Okay. So you did say the form-grabber for Kronos, then?

Hutchins: Not the form-grabber for Kronos. It was an earlier one released in about I’m gonna say 2014?

Chartier: And what was the name of that?

Hutchins: Oh, fuck. I really can’t remember. No, I’m drawing a blank. I mean, like, I actually sell the code. I sell it to people and then they do what the fuck they want with it.

They also have a jail transcript of Hutchins telling his boss that he gave Randy malware to pay off a debt. [Note, the defense has taken issue with the accuracy of this transcript.]

Hutchins: Yeah, and there were also some logs that I gave the compiled binary to someone to repay a debt

Salim Neino: You gave a compiled binary to somebody on the chat log?

Hutchins: To repay a debt yeah

[snip]

Neino: Okay, um was the nature of the debt anything significant?

Hutchins: It was about five grand

Neino: Oh not the amount, but was the nature of the debt significant, like was it related to something else, or just your personal debt?

Hutchins: Um he, no he asked me to hold some Bitcoins for him, and my software fucked up, and I lost some of the money

Neino: Oh so you had to pay him back?

Hutchins: Yeah

So while Hutchins did not himself use malware to steal information for the purpose of financial gain, they arguably have him admitting that he sold code that stole information for financial gain and that he gave code that did the same to someone who stole information for financial gain in order to pay off a $5,000 debt. Now, the government still has some work to do to prove that Hutchins’ code had that intent, but at least for this charge they don’t have to point to 10 computers that he intended to damage.

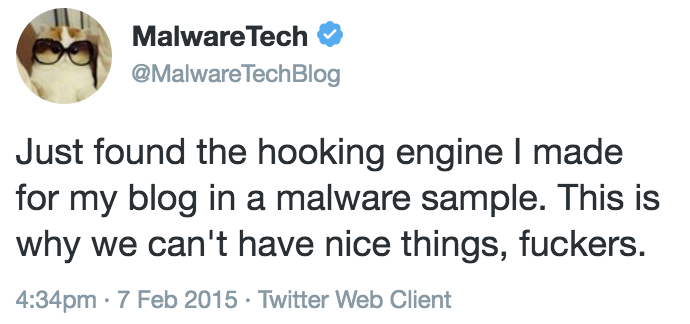

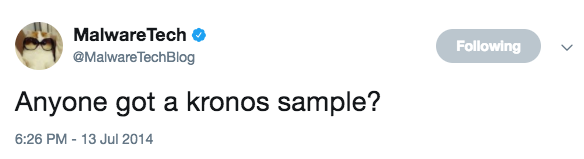

As for the wire fraud, I’m not sure (and I’m not sure the defense is either) but I think they’re now taking a post Hutchins did, criticizing weaknesses in a piece of malware competing with Kronos, and claiming that the post served to defraud upstanding malware purchasers into believing that Kronos was a better product by comparison.

On or about December 23, 2014, defendant MARCUS HUTCHINS hacked control panels associated with Phase Bot, malware HUTCHINS perceived to be competing with Kronos. In a chat with [Randy], HUTCHINS stated, “well we found exploit (sic) [sic] in this panel just hacked all his customers and posted it on my blog sucks that these [] idiots who cant (sic) [sic] code make money off this :|” HUTCHINS then published an article on his Malwaretech blog titled “Phase Bot — Exploiting C&C Panel” describing the vulnerability.

The government may even be planning on arguing that Hutchins used his research into the competition to update Kronos.

In or around February 2015, MARCUS HUTCHINS and [VinnyK], updated Kronos. On February 9, 2015, in a chat with [Randy], HUTCHINS described the update. [Randy] asked, “[D]id you guys just happen to make a (sic) update?” HUTCHINS responded, “[W]e made a few fixes to both the panel and bot.” [Randy] replied, “ah okay yeah read something that vinny posted was curious on what it was exactly.”

In any case, now that the government knows they’re not going to be able to hide Randy, they can use Hutchins’ interactions with him to try to put Hutchins in a cage, when they’ve decided to spare Randy that same cage or at least limit the time he’ll be there.

If I’m right about this, a lot of it brings us back to the final new charge, false statements. The government has charged Hutchins with lying to the same FBI agents that Hutchins accused (with some basis) of lying on the stand. They claim he lied when he told the FBI that “he did not know his computer code was part of Kronos until he reverse engineered the malware sometime in 2016,” because “as early as November 2014, HUTCHINS made multiple statements to [Randy] in which HUTCHINS acknowledged his role in developing Kronos and his partnership with [VinnyK].”

In yesterday’s status report, the defense said they’re going to “request that the government particularize the alleged false statement of Count Nine.” Presumably, they want to know how it is that AUSA Dan Cowhig, on August 4, 2017, represented to a judge that, “Hutchins admitted that he was the author of the code that became the Kronos malware” but are now claiming that he did not admit that. It may well be the language I’ve cited above, where Hutchins cites the UPAS Kit (which he coded as a minor), but says that was not the form grabber used in Kronos.

That’s the kind of charge that not only will depend on the specific language the government has in mind (which is why the defense may well succeed with a bill of particulars demand where they otherwise might not), but also the understanding of how fragments of code become malware, something on which (if Agent Chartier’s past testimony was any indication) the defense is likely to have a much better grasp than the government.

Understand where that puts us, though.

Probably after rediscovering Hutchins’ access to VinnyK and his friends because he had saved the world from repurposed NSA hacking tools, the government slapped together charges in a bid to turn Marcus Hutchins into an informant. When that didn’t work, when Hutchins had the gall to point out how problematic the charges were, the government then upped the ante, turning Hutchins into the primary target, whereas previously VinnyK had been.

We’ve got VinnyK, who used to be considered a big enough criminal to do this to Hutchins, Randy, who the government readily admits stole money from actual Americans, and the guy who saved the world from tools the NSA couldn’t keep safe. You’ve got two FBI agents who have done remarkable work damaging their own credibility (to say nothing of their ability to appear knowledgable about computer code on the stand). And the American taxpayers are going to spend thousands of dollars to try to put Hutchins — and possibly only Hutchins — in prison. That, even though the false statements charges may well come down to a dispute — which both sides have already been arguing — what the definition of malware is.

This is, in many ways, all too typical of how our justice system works; Hutchins is not unique in being targeted this way, nor in having the government double down when he had the nerve to avail himself of the justice system.

But I keep coming back to this: why does the government think that the interests of justice are served for punishing a guy because he achieved renewed notice by doing something good?