[NB: Check the byline, thanks. /~Rayne]

I’ve been meaning to write about this for a while. Push came to shove with Marcy’s post this past week on Roger Stone and the Russian hack of the DNC’s emails as well as her post on Rick Gates’ status update which intersects with Roger Stone’s case.

First, an abbreviated primer about cloud computing. You’ve likely heard the term before even if you’re not an information technology professional because many of the services you use on the internet rely on cloud computing.

Blogging, for example, wouldn’t have taken off and become popular if it wasn’t for the concept of software and content storage hosted somewhere in a data center. The first blogging application I used required users to download the application and then transfer their blogpost using FTP (file transfer protocol) to a server. What a nuisance. Once platforms like Blogger provided a user application accessible by a browser as well as the blog application and hosting on a remote server, blogging exploded. This is just one example of cloud computing made commonplace.

Email is another example of cloud computing you probably don’t even think about, though some users still do use a local email client application like Microsoft’s proprietary application Outlook or Mozilla’s open source application Thunderbird. Even these client applications at a user’s fingertips rely on files received, sent, managed, and stored by software in a data center.

I won’t get into more technical terms like network attached storage or storage area network or other more challenging topics like virtualization. What the average American needs to know is that a lot of computing they come in contact every day isn’t done on desktop or laptop computers, or even servers located in a small business’s office.

A massive amount of computing and the related storage operates and resides in the cloud — a cutesy name for a remotely located data center.

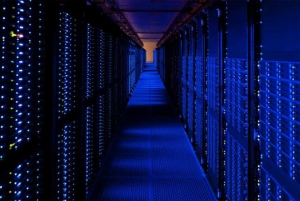

This is a data center:

Located in Council Bluffs, Iowa, this is one of Google’s many data centers. In this photo you can see racks of servers and all the infrastructure supporting the servers, though some of it isn’t readily visible to the untrained eye.

This is another data center:

This is an Amazon data center, possibly one supporting Amazon Web Services (AWS), one of the biggest cloud service providers. Many of the sites you visit on the internet every day purchase their hosting and other services from AWS. Some companies ‘rent’ hosting space for their email service from AWS.

Here’s a snapshot of a technician working in a Google data center:

Beneath those white tiles making up the ‘floor’ are miles and miles of network cables and wiring for power as well as ventilation systems. More cables, wires, and ventilation run overhead.

Note the red bubble I’ve added to the photo — that’s a single blade-type server inserted into a rack. It’s hard to say how much computing power and storage that one blade might have had on it because that information would have been (and remains) proprietary — made to AWS specifications, which change with technology’s improvements.

These blades are swapped out on a regular maintenance cycle, too, their load shifted to other blades as they are taken down and replaced with a new blade.

Now ask yourself which of these servers in this or some other data center might have hosted John Podesta’s emails, or those of 300 other people linked to the Clinton campaign and the Democratic Party targeted by Russia in the same March 2016 bulk phishing attack?

Not a single one of them — probably many of them.

And the data and applications may not stay in one server, one rack, one site alone. It could be spread all over depending on what’s most efficient and available at any time, and the architecture of failover redundancy.

~ ~ ~Some enterprises may not rely on

software-as-a-service (SaaS), like email, hosted in a massive data center cloud. They might instead operate their own email server farm. Depending on the size of the organization, this can be a server that looks not unlike a desktop computer, or it can be a server farm in a small data center.

(The Fortune 100 company for which I once worked had multiple data centers located globally, as well as smaller server clusters located on site for specialized needs, ex. a cluster collecting real-time telemetry from customers. Their very specific needs as well as the realistic possibility that smaller businesses could be spun off required more flexibility than purchasing hosted services could provide at the time.)

And some enterprises may rely on a mix of cloud-based SaaS and self-maintained and -hosted applications.

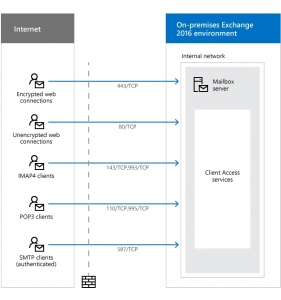

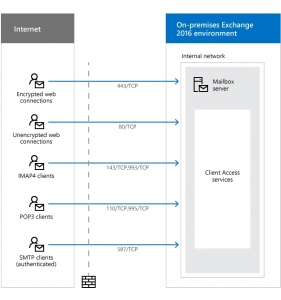

In 2016 the DNC used Microsoft Exchange Server software for its email across different servers. Like the much larger Google-hosted Gmail service, users accessed their mail through browsers or client applications on their devices. The diagrams reflecting these two different email systems aren’t very different.

This is a representation of Google’s Gmail:

[source: MakeInJava(.)com]

This is a representation of Microsoft Exchange Server:

Users, through client/browser applications, access their email on a remote server via the internet. Same-same in general terms, except for scale and location.

If you’ve been following along with the Trump-Russia investigation, you know that there’s been considerable whining on the part of the pro-Trump faction about the DNC’s email server. They question why a victim of a hack would not have turned over their server to the FBI for forensic investigation and instead went to a well-known cybersecurity firm, Crowdstrike, to both stop the hack, remove whatever invasive tools had been used, and determine the entity/ies behind the hack.

A number of articles have been written explaining the hacking scenario and laying out a timeline. A couple pieces in particular noted that turning over the server to the FBI would have been disruptive — see Kevin Poulsen in The Daily Beast last July, quoting former FBI cybercrime agent James Harris:

“In most cases you don’t even ask, you just assume you’re going to make forensic copies…For example when the Google breach happened back in 2009, agents were sent out with express instructions that you image what they allow you to image, because they’re the victim, you don’t have a search warrant, and you don’t want to disrupt their business.”

Poulsen also quantified the affected computing equipment as “140 servers, most of them cloud-based” meaning some email and other communications services may have been hosted outside the DNC’s site. It would make sense to use contracted cloud computing based on the ability to serve widespread locations and scale up as the election season crunched on.

But what’s disturbing about the demands for the server — implying the DNC’s email was located on a single computer within DNC’s physical control — is not just ignorance about cloud computing and how it works.

It’s that demands for the DNC to turn over their single server went all the way to the top of the Republican Party when Trump himself complained — from Helsinki, under Putin’s watchful eye — about the DNC’s server:

“You have groups that are wondering why the FBI never took the server. Why didn’t they take the server? Where is the server, I want to know, and what is the server saying?”

And the rest of the right-wing Trumpist ecosphere picked up the refrain and maintains it to this day.

Except none of them are demanding Google turn over the original Gmail servers through which John Podesta was hacked and hundreds of contacts phished.

And none of the demands are expressly about AWS servers used to host some of DNC’s email, communications, and data.

The demands are focused on some indeterminate yet singular server belonging to or used by the DNC.

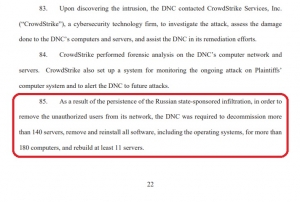

~ ~ ~The DNC had to shut down their affected equipment and remove it from their network in order to clean out the intrusion; some of their equipment had to be stripped down to “bare metal,” meaning all software and data on affected systems were removed before they were rebuilt or replaced. 180 desktops and laptops had to be replaced — a measure which in enterprise settings is highly disruptive.

Imagine, too, how sensitive DNC staff were going forward about sharing materials freely within their organization, not knowing whether someone might slip and fall prey to spearphishing. There must have been communications and impromptu retraining about information security after the hack was discovered and the network remediated.

All of this done smack in the middle of the 2016 election season — the most important days of the entire four-year-long election cycle — leading into the Democratic Party’s convention.

(This remediation still wasn’t enough because the Russians remained in the machines into October 2016.)

If the right-wing monkey horde cares only about the DNC’s “the server” and not the Google Gmail servers accessed in March 2016 or the AWS servers accessed April through October 2016, this should tell you their true aim: It’s to disrupt and shut down the DNC again.

The interference with the 2016 election wasn’t just Russian-aided disinformation attacking Hillary Clinton and allies, or Russian hacks stealing emails and other files in order to leak them through Wikileaks.

The interference included forcing the DNC to shut down and/or reroute parts of its operation:

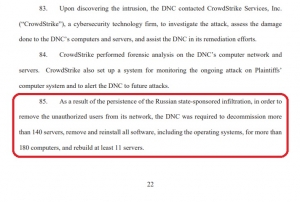

(excerpt, p. 22, DNC lawsuit against Russian Federation, GRU, et al)

(excerpt, p. 22, DNC lawsuit against Russian Federation, GRU, et al)

And the attack continues unabated, going into the 2020 general election season as long as the right-wing Trumpists continue to demand the DNC turn over the server.

There is no one server. The DNC shouldn’t slow or halt its operations to accommodate opponents’ and suspects’ bad faith.

~ ~ ~As for Trump’s complaint from Helsinki: he knows diddly-squat about technology. It’s not surprising his comments reflected this.

But he made these comments in Helsinki, after meeting with Putin. Was he repeating part of what he had been told, that Russia didn’t hack the server? Was he not only parroting Putin’s denial but attempting to obstruct justice by interfering in the investigation by insisting the server needed to be physically seized for forensic inspection?

~ ~ ~With regard to Roger Stone’s claims about Crowdstrike, his complaints aren’t just a means to distract and redirect from his personal exposure. They provide another means to disrupt the DNC’s normal business going forward.

The demands are also a means to verify what exactly the Special Counsel’s Office and Crowdstrike found in order to determine what will be more effective next time.

The interference continues under our noses.

This is an open thread.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)