Joshua Schulte Wanted to Include Instructions to Contact WikiLeaks in a Pro Se Motion

The lawyers for accused Vault 7 leaker Joshua Schulte made a last ditch effort yesterday to limit how much information from his prison notebooks can be admitted as evidence in his trial starting next week. Perhaps inadvertently, the letter provides new details about why the government believes Schulte was trying to leak from jail, as well as some hints about why his lawyers claim they may be responsible for some of his exposure on those charges.

As I had noted, the government wants to include a passage from his notebooks instructing somebody to “ask WikiLeaks” if they need help to prove that Schulte had knowledge of what WikiLeaks had received.

“Ask WikiLeaks” (014099) (undated): In the middle of the page, the defendant writes, “If you need help ask WikiLeaks for my code.”3 The defendant’s direction to consult WikiLeaks about his “code” is admissible as Nonpublic Information Evidence, because it is a statement that WikiLeaks is in possession of source code for tools upon which the defendant worked and that are contained in the back-up file that was stolen, even though WikiLeaks has not publicly disclosed that it possesses any source code for all of the tools. Schulte’s knowledge of non-public aspects of the information that was given to WikiLeaks helps to demonstrate that he was the one who gave that information to WikiLeaks in the first place.

Schulte’s lawyers argue, unpersuasively, that this is not relevant, though they also argue that it is “privileged information or work product” because the passage is part of a pro se motion Schulte was trying to draft.

- “If you need help ask WikiLeaks for my code.” Gov. Ltr. 8. The government says that this sentence means that “WikiLeaks is in possession of source code for tools upon which the defendant worked and that are continued in the backup file that was stolen, even though WikiLeaks has not publicly disclosed that it possesses any source code for all of the tools.”

Nothing in the unredacted portion of Page JAS_022627 (classified #014099) is relevant to the government’s case. On the contrary, the beginning of the page is clearly part of a legal motion that Mr. Schulte was drafting. The top of the page states: “You can create a forensic copy of the device & then have control over it. There has been no reason over this past year that we would not have had access to this critical evidence except that the prosecutors have lied to your honor & played games.” This is privileged information or work product and is therefore not admissible.

Obviously, Schulte’s lawyers are wrong that this is not relevant to the government’s case, either on the MCC charges or the charges in chief. They don’t deny that this reflects knowledge that WikiLeaks has source code that Schulte wrote; they simply remain silent about it.

They’re instead making a half-hearted attempt to argue that it pertains to Schulte’s defense. That is, they’re arguing that in a pro se motion addressed to Judge Crotty, Schulte included instructions about how to use the code he wrote for the CIA to do something, possibly obtain forensic evidence from the CIA that the government had not yet turned over.

While the privilege claim, half-hearted as it is, is an interesting one, Schulte’s argument in some ways makes this passage more damning. After all, he had already, by this point, included allegedly classified information in a pro se bail motion. Around this period he tried to release information publicly via a pro se motion again, though the government pulled it from PACER before most people could access it. Schulte eventually would submit a pro se lawsuit challenging his SAMs designation that happened to make many of the same claims he had made in his “Presumption of Innocence” blog and alluded to some of the same challenges he had tried to make to warrants by leaking protected or classified information (though the government has not claimed it included classified information). That is, the record suggests that Schulte was using his pro se motions to communicate publicly as much as to mount legal arguments (though his pro se motion raises some important points about our shitty criminal justice system amid a lot of dreck and lies).

That makes the second part of what Schulte’s lawyers claim was a planned pro se motion all the more interesting. The government wants to present a page that appears 37 Bates stamp numbers later in Schulte’s notebook which lists a bunch of potentially classified topics.

“What We Expect to Find in Emails” (014136) (undated): At the top of this page, the defendant writes “What we expect to find in emails.” On the remainder of the page, the defendant writes a list of items, many of which contained classified information. This portion of the Blue Notebook is admissible as Intent Evidence and MCC Classified Information Evidence, because it shows the defendant cataloguing classified information that, if publicly disclosed, would likely be harmful to the United States. Indeed, some of the categories of information identified by the defendant on this page—such as certain operations—is the same as the classified information contained in the Fake Authentication Tweet, which serves to show that the defendant’s intent was to collect these materials for dissemination, not for any legitimate purpose related to his defense.

As noted, Schulte claims that this passage was not part of Schulte’s planned “New Articles,” which appears 22 pages earlier in the notebook, but instead the pro se motion. His defense claims this was a Fifth Amendment one, which I’m not sure I understand; it seems more like a selective prosecution challenge, but then they’re not engaging with the substance here.

What We Expect to Find in Emails (014136) (undated). This page is clearly part of Mr. Schulte’s pro se motion to dismiss under the Fifth Amendment for prosecutorial misconduct. The Fifth Amendment is referenced at the top of the right-hand page. As such it is privileged work product. In addition, the government has not specified which part of this page contains classified information and because the handwriting is not always legible the defense cannot fairly guess the offending part. Again this seems more a statement of Mr. Schulte’s political viewpoint, now as a wrongfully charged and detained defendant, and even were it not privileged, it would be irrelevant and unduly prejudicial.

In any case, even Schulte’s own lawyers are saying that Schulte wanted to submit a pro se motion that, first, instructed someone to use a tool he wrote for the CIA that could be obtained by asking WikiLeaks, possibly to find a bunch of email that includes classified information about CIA operations.

I can see how, in the wake of being busted once trying to spread protected information via pro se motion, his attorneys might advise him to draft any pro se motions in his notebook (at the time he had a classified discovery computer, but it’s not clear what he could write and save on it), which they could then review to make sure he wasn’t getting himself in more legal trouble. But then, when it was discovered, the government used it to claim he intended to leak more classified information.

Yet Schulte’s letter — in conjunction with evidence the government has said they’d submit at trial if the attorney-client advice issue came up — makes it clear that he was unhappy with his lawyer, Sabrina Shroff’s advice.

Finally, the government’s more general assertion that the conflict surrounding the MCC notebooks has somehow “disappear[ed]” based on the court’s ruling over objection that Mr. Schulte may not raise an advice-of-counsel defense is also incorrect. Gov. Ltr. 1. Indeed, the specific pages the government seeks to introduce include work product in preparation for Mr. Schulte’s defense. Some the pages that the government seeks to introduce also specifically mention “Sabrina” and refer to his family reaching out to different defense lawyers, strongly implying that Mr. Schulte had concerns about his current defense team. These portions of the notebooks only highlight the inherent conflict that the current defense team faces in representing Mr. Schulte. Additionally, if Mr. Schulte is convicted, this issue will surely be taken up on appeal, and may well cause a reversal of a conviction. The issue will only begin to “disappear” if the notebooks are excluded from the trial.

The government could easily show — and will, when Schulte appeals based on this argument — that at the time Shroff was trying to get him to stop trying to go public, he was threatening to go around her.

For example, the Government has described to the defense how, if the defendant offered his counsel’s testimony, the Government would likely rely on recorded prison calls in which the defendant criticized defense counsel’s advice, including, for example, calls in which the defendant stated that he would “go around” Ms. Shroff to disclose information to the media, despite her objections to this strategy.

In other words, written at a time when Schulte was trying to bypass Shroff, submitting a pro se motion including instructions on how to get and use one of the hacking tools he wrote, possibly to obtain classified emails, it could be seen as an attempt to use the pro se motion to leak information (or instruct others how to get and leak it). There’s no chance that that address, “If you need help ask WikiLeaks for my code,” was intended for Judge Crotty (who, in his writings, Schulte describes in very unfavorable terms), after all. Nor is it clear how someone as smart as Schulte is would include information confirming his role in the leak in a pro se motion claiming that prosecutors had unfairly targeted him.

All of which makes it interesting, to me, that this last-ditch letter addressing Schulte’s notebooks mounts an effort to get all reference to Anonymous, specifically, excluded from trial.

The government also again makes repeated reference to the “Anonymous” group. Dkt 257, at 5, 12, 17. As explained in our response to the motions in limine, all reference to Anonymous should be excluded under Rule 404(b).

[snip]

The defense continues to object to any mention of Autonomous [sic] as unduly prejudicial and because it may confuse the jury.

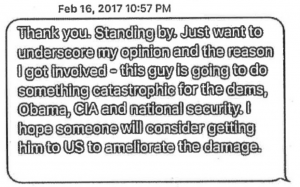

The government has said it will introduce evidence that Schulte, in real time in 2010, opined that Chelsea Manning’s leaks to WikiLeaks had done damage, which not only proves that he followed historical WikiLeaks releases but believed that the way WikiLeaks had released her leaks did some damage. That piece of evidence is utterly damning in support of a claim that Schulte intended to damage the US with his alleged leaks. And the defense is focusing, instead, on Schulte’s self-proclaimed reference to Anonymous?!?!?

While Schulte’s team doesn’t specifically reference which arguments it relies on here, weeks ago, the defense made this argument about why mentioning Anonymous would be prejudicial.

The government has provided no justification to introduce comments about Anonymous, which must be excluded under Rule 404(b). The government offers no support why it should be allowed to introduce “additional communications with the Reporter, including encrypted communications in which [Mr.] Schulte claims to have been [a] member of the group Anonymous, which is a group known for conducting cyber-attacks that has provided documents to WikiLeaks in the past.” Gov. Mot. 33. This “additional” evidence is clearly not part of the charged offenses nor is it inextricably intertwined with them. The jury will discern no gaps in the government’s case if it is not included in the proof. Instead, it is just classic “bad act” evidence that would be purely prejudicial. The evidence of claimed participation in a shadowy, underground group infamous for cyber-attacks and dumping on WikiLeaks is unduly prejudicial as it suggests concerted activity of a type even more disturbing than what is charged.

[snip]

The government also states that Mr. Rosenzweig will testify that in 2012 “Anonymous and WikiLeaks worked together to release information.” Gov. Res. 13. This testimony will “aid the jury in understanding the hacking group’s relationship with WikiLeaks” and that Mr. Schulte had “contact with access to WikiLeaks. Gov. Res. 13. As explained above, supra Point II(C)(1), information about Anonymous should be excluded from the trial.

That is, when Schulte’s team wrote this weeks ago (when they were trying unsuccessfully to exclude Paul Rosenzweig’s testimony about what Anonymous is and its past relationship with WikiLeaks), they focused only on the prejudicial aspect. Now, they’re claiming that discussion of Anonymous will confuse the jury, except that’s precisely why the government wanted Rosenzweig to explain what Anonymous is.

But we now know how inadequate this argument is.

Remember: the letter Schulte sent yesterday is an attempt to get Schulte’s notebooks (or at least the most damning parts of them) excluded from trial. But their reference to the government’s plan to introduce references to Anonymous in the letter actually draws from four different kinds of evidence: his notebooks, the Samsung phone he used in jail, and Signal texts and ProtonMail he used to contact a reporter (who warrant affidavits and recent filings have confirmed is WaPo’s Shane Harris).

Partly, the references to Anonymous prove that Schulte used the Samsung phone and the Annon ProtonMail account (the passwords for the ProtonMail accounts were also in the notebook), and that therefore the Signal texts that remain on the phone were sent by him.

In his correspondence with the Reporter, the defendant, pretending to be the defendant’s family and friends, asked the Reporter to send him the versions of the defendant’s articles that the defendant and his family had previously provided to the Reporter. When the Reporter demurred and sought confirmation from the defendant’s family whether the Reporter could provide the defendant’s articles to the user of the Annon Account, the defendant, posing as a member of his family, used a secure messaging application, Signal, to authorize release of the articles. In these Signal communications (the “Signal Messages”), the defendant claimed that the user of the Annon Account was a member of the hacktivist group Anonymous, of which, according to the defendant, the defendant was once a member. Anonymous has collaborated in the past with WikiLeaks to disclose stolen sensitive information.

[snip]

Signal and Twitter to Send Articles and Tweets (014327) (Sept. 2, 2018): In this portion of the Red Notebook, Schulte writes, among other things, “Well its September now. Locked in all day. Hopefully tonight I can setup Signal from my cell & msg [last name of the Reporter] to confirm anon’s permission and get my fucking articles. I also need to confirm my twitter.” This page contains Use Evidence. In particular, the defendant references setting up Signal “from my cell”—which supports that the defendant was using Signal on the Samsung Phone—to confirm “anon’s permission”—which shows that the defendant was using the Anon Account to “get [his] fucking articles.” The defendant also made clear that he had created a Twitter account when he wrote “I also need to confirm my twitter.”

[snip]

The Samsung Phone: Although the Samsung Phone was not found in the defendant’s cell, the Government intends to show that it was one of the cellphones that the defendant used at the MCC through various pieces of evidence, including by comparing identifying information appearing on the Samsung Phone to one of the images taken by CW-1 of one of the cellphones the defendant used in prison. The Samsung Phone contains, among other things, evidence that Encrypted Email Accounts were accessed on the cellphone, but not the actual communications from those accounts. The Samsung Phone also contains the Signal Messages in which the defendant, among other things, pretended to be a third person and attempted to convince the Reporter that the user of one of the Encrypted Email Accounts with whom the Reporter was corresponding (but who was in fact the defendant) is a member of the online hacktivist group Anonymous who is trying to help the defendant.

The Encrypted Email Accounts: The Annon Account contains the defendant’s correspondence with the Reporter, including the September 2018 Emails that attached the classified Network Structure Document and the Protected Search Warrant. The other Encrypted Email Accounts also contain records related to the defendant’s use and control of the Social Media Accounts, such as, for example, email notifications when the defendant modified the Social Media Accounts.

If I understand all this correctly, not only did Schulte use a ProtonMail account claiming to be a member of Anonymous to send details of CIA’s network structure to Harris (one of the charged pieces of classified information), but also used it to try to get him to send Schulte the original copies of his blog posts. Schulte was pretending to be a member of Anonymous on ProtonMail and a member of his family on Signal. And Schulte documented that scheme in his notebook in some of the references that Schulte’s lawyers want to exclude (though which they don’t lay out in such a way to show how it glues everything Schulte was doing from jail together).

But there’s still one more reference of Anonymous, tying it directly to the content that Schulte wanted to release: the Malware of the Mind article that reportedly discussed what he did at CIA.

Identifying Malware of the Mind as Article 10 (014319): On this page, the defendant identifies the Malware Article as article 10: “I’m hoping to write /edit my 9 articles. I don’t know how I can them—oh I may text [the Reporter] from [my cousin’s] number. Omar claims that some service exists to do this – I’m dubious. [Redacted]. Although I feel this may not work either . . . IDK Basically on hold for my publication. Secondly, I want to rewrite article #10: Malware of the Mind!” After a line drawn on the page, the page also includes, among other things, the phrase “Anonymous,” and the phrase “classified information.” This entry includes Intent Evidence, in that it shows that the defendant plans to re-draft his articles, including the Malware Article. Furthermore, the defendant’s statement that he might text the Reporter from his cousin’s telephone number, thus continuing to conceal his identity during those communications, is Guilty Conscience Evidence. Finally, the defendant’s reference to “Anonymous” and “classified information” is consistent with the defendant’s claims in his Signal messages that Anonymous is seeking to help prove his innocence by providing information to the Reporter.

The defense claims all this is prejudicial because, “it suggests concerted activity of a type even more disturbing than what is charged.” Except, by claiming that Schulte planned to include instructions in a pro se motion that people other than Judge Crotty — people with access to WikiLeaks — might use go get the code he wrote from WikiLeaks, possibly to obtain emails of classified information suggests that may well be what Schulte was attempting.

The government and Schulte are also arguing over what measures the government can use to protect the identities of a slew of CIA witnesses who will testify. Schulte has good reason to complain. In past trials (Jeffrey Sterling’s trial is being cited as precedent), the government engaged in a great deal of theater to make CIA witnesses — including witnesses whose CIA tie had already been declassified, as some of the witnesses here have been — seem especially momentous. Some of that is undoubtedly going on here. But if the government believes (and this letter from his defense does nothing to rebut that belief) that Schulte is using every opportunity in his prosecution to leak more information, there’s actually a solid case for some of those measures.

As I disclosed in 2018, I provided information to the FBI in 2017. The government recently stated publicly that matters on which I shared information are related to Schulte. Aside from two press inquiries, I have not spoken with the government about Schulte.