BMS: Breast Milk Substitute? Big Messy Situation [UPDATE-1]

[NB: check the byline, thanks. Updates will appear at the bottom of this post. /~Rayne]

For starters, let me point out the Biden administration has been trying to resolve the current infant formula crisis.

Today, I spoke with retailers and manufacturers to discuss ways we can all work together to do more to help families access infant formula.

My team is working overtime to increase supply as quickly as possible without compromising safety. pic.twitter.com/LATXCZ8Wxc

— President Biden (@POTUS) May 12, 2022

The Biden-Harris Administration is working overtime to ensure infant formula is safe and available for families across the country.

For resources on how you can access infant formula, visit https://t.co/uGVfPvK87c.

— The White House (@WhiteHouse) May 14, 2022

Other media outlets have done a decent job analyzing and reviewing the underlying causes of a disastrous shortage of infant formula in the U.S.

The causes include Trump maintaining bullshit tariffs on Canadian dairy products, COVID interruptions, and the oligopoly of formula producers which came about through the usual capitalistic method of regulatory capture leading to exclusion of competition and an insufficiency of monitoring for food safety.

The short term fixes may not be immediate; China, for example, manufactures formula but it has been struggling with COVID. It’s also had problems in the past with adulteration of infant formula.

Canada is the most obvious closest source but it will take rapid unwinding Trump’s tariffs to allow Canadian formula to backfill demand.

Meanwhile shelves are rapidly emptying depending on location across the country.

This morning, I drove around for an hour in Norfolk (mostly OV, East Beach, Wards Corner) looking for baby formula.

Here’s a summary (as of about 10am) in case it’s helpful to other local parents: pic.twitter.com/ejfPAHJx0q

— Phil Hernandez (@PhilforVirginia) May 14, 2022

Mothers in particular are frantic because they are not only worried about ensuring a regular supply of formula for their infants, but they are being harangued and shamed for not breastfeeding even though breastfeeding isn’t a universal option for all mothers and infants.

This tweet by Midler is extremely disappointing. There are so many reasons why women can’t breastfeed yet they are constantly pressured for not doing so even by other women who should know better.

This is a really excellent thread by a historian on infant formula and breast milk substitutes which explains some of the reasons why parents have not been able to offer breast milk throughout history.

You may be hearing the argument that before the rise of modern commercial infant formula, babies all ate breastmilk and everything was great. As a historian of infant feeding, let me tell you why that’s not true.

— Carla Cevasco, PhD (@Cevasco_Carla) May 11, 2022

Much of the ignorance about infant feeding and subsequent harassment of mothers is rooted in Americans’ inadequate education about human reproduction as well as basic biology. Adults who’ve graduated from high school should know that mammals produce milk in response to a pregnancy, and once nursing has stopped so, too, does maternal milk production.

A mother can’t simply choose to breastfeed if she had to stop for any reason like difficulty with infant latch on, physical disability, illness, return to work where she can’t readily pump breast milk in privacy, so on.

The worst examples of pressure come from men who know absolutely nothing about breastfeeding having no uterus or birthed a child, and having no breasts. They know nothing of the stress of learning how to feed a newborn, mastering the intricacies of breastfeeding brassieres, learning how to do so in view of others as necessary, how to deal with curiosity or disgust by others who are offended by breastfeeding, how to pump and store breast milk, how to deal with chapped and bleeding nipples as well as unwanted letdown of milk, how to handle the first few times an infant bites its mother’s nipples, and dealing with constant advice and criticism about breastfeeding one’s child from family, friends, and total strangers.

And yet they feel they can lecture women saying, “Just breastfeed the kid.”

The stress new mothers deal with in this country is enormous. It’s no wonder we have a couple generations of anxious children and adults when they literally nurse on this as infants.

~ ~ ~

This situation isn’t going to get better overnight. It’s going to take at least a couple of months before production is up to demand levels and safe for infants.

What are parents who can’t breastfeed and can’t find formula supposed to do?

The White House put together a fact sheet which contains resources for locating formula.

https://www.hhs.gov/formula/index.html

For some parents the first step is finding a breast milk bank nearby; the fact sheet includes a link to

https://www.hmbana.org/find-a-milk-bank/overview.html

But even with all these resources there may be parents who can’t locate formula and are too far from the nearest breast milk bank. In Michigan, for example, there are two banks listed but both are more than 9 hours drive from the largest city in the Upper Peninsula, and the closest to Detroit is still more than an hour’s drive.

What do these parents do?

Having a handful of young friends who are expecting a child within the next six months, I did some research on how we used to feed infants before commercial infant formula was so prevalent.

First, I checked both the World Health Organization and UN’s UNICEF to obtain any resources they offered parents as breast milk substitutes in the event of an emergency.

UNICEF was unhelpful. Their material focused on ready-to-use formula in lieu of breastfeeding, only after pages and pages of material emphasizing human breast milk as a preference over formula. The organization has rightfully worked hard to emphasize breastfeeding as the safest and most reliable method for feeding infants in no small part because breast milk contains bioactive agents formula does not. The organization has fought globally against corporations which have undermined breastfeeding in order to sell commercial infant formula. But for the U.S.’s current situation UNICEF’s policy doesn’t work.

WHO was marginally better; a 43-page brochure spent 39 pages repeating over and over how human breast milk was the best choice for infants, nearly ignoring crises where breast milk and formula were not options.

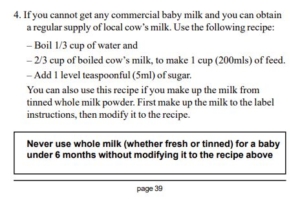

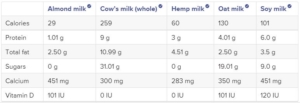

Thankfully, on page 39 there was a recipe for making an alternative suitable for nursing infants — it consisted of water, evaporated milk, and sugar.

I recalled my youngest sibling adopted at 3 months of age in the early 1970s not consuming commercial formula. Instead they consumed a recipe based on cow’s milk, and this recipe in WHO seemed very similar.

Fortunately, I still have a resource to validate the recipe was the same or very similar. I called my 82-year-old mother and asked her what parents did before casual infant formula was used widely. I told her what I’d found at WHO.

“That’s what you drank,” she said. “That’s what you, your natural siblings and adopted sibling drank. Evaporated milk, water, and sugar, though we used corn syrup instead of sugar to avoid constipation. Oh, and you had infant oral vitamin drops.”

We spent a half hour talking about the hows and whys — she had been working full time as a registered nurse and couldn’t breastfeed her kids. Breastfeeding wasn’t widely seen as socially acceptable either if a mother had to feed an infant outside of the home.

Hygiene was emphasized — ensuring the bottles, lids, and nipples were sterile, that all formula recipe ingredients were heated to kill pathogens and bottled while hot to ensure the formula was safe to consume, along with prompt refrigeration.

Apart from human breast milk having evolved to best suit human infant needs, hygienic production, bottling, and storage are the key reasons why WHO and UNICEF place a premium on breastfeeding over formula and alternatives. Depending on location in the world, the only safe food for an infant may be breast milk especially since water for dry formula mix or use with concentrated canned formula may not be clean.

But one or two generations of Americans were fed canned cow’s milk diluted with water with additional calories supplemented by sweetener. In a pinch we can do it again — at least until the canned milk production supply chain breaks down.

~ ~ ~

CAVEAT: I am NOT a health care professional. I am providing the following on an informational basis which should not be used as a substitute for discussion and guidance with a qualified health care professional.

After talking with my mom I’m sharing what I found on the internet which was what doctors and hospitals used to send home with their new parents as instructions for feeding their new infant, along with the WHO recipe.

Vitamins: For anyone nearing their due date or who has an infant under the age of 6 months: contact your pediatrician or health care provider for a recommendation on infant liquid multivitamin drops and whether they recommend them with or without iron if an alternative to infant formula or breast milk is necessary. Multivitamin drops will supplement what an alternative to formula can’t provide should breastfeeding not be an option.

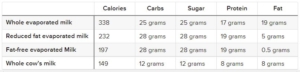

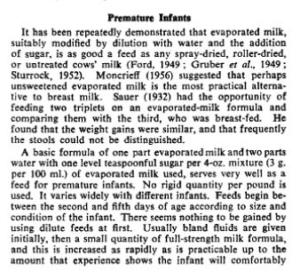

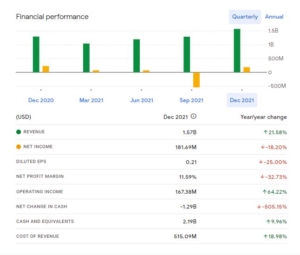

Nutritional differences: Keep in mind that the evaporated milk alternative is not identical to breast milk; it has more far more protein, for example, which may be more taxing on human kidneys. Compare these different forms of cow’s milk to human breast milk:

Human breast milk (per 8-oz cup): 171 calories, 17 grams carbs, 17 grams sugar, 2.5 grams protein, 11 grams fat

Gut flora: Also keep in mind that a change in diet means a change in gut flora; an infant can become constipated or have other health issues like allergies due to a corresponding change in immune system signaling. Parents should consider broad spectrum probiotics in their own diet because they will pass on their flora through normal contact with their infant. I introduced my children to plain unsweetened yogurt as soon as our family GP approved the addition to their diet (about 6 months); yogurt with live culture is a probiotic food.

WHO’s alternative:

Note that this formulation allows for the use of boiled cow’s milk. NEVER use raw cow’s milk. It’s safest to boil pasteurized cow’s milk. The formulation also allows for canned evaporated milk once it has been reconstituted to the same concentration as fresh milk, and then diluted further per this recipe.

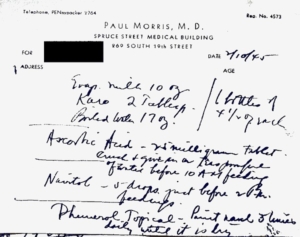

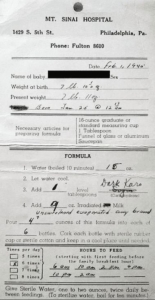

Past examples: These are examples of instructions routinely sent home with new parents in the 1940s through the early 1960s.

Here’s an excerpt from a paper published in 1957 on evaporated milk in infant feeding.And an instructional video on how infant formula was prepared at home during the 1950s at this link.

Some recipes like WHO’s call for sugar, but many older recipes refer to corn syrup as a sweetening alternative because it prevents or resolves constipation in some infants.

At least one recipe published by a mommy blog refers to blackstrap molasses as a sweetener because it contains iron and other trace minerals not found in white sugar or white corn syrup.

NEVER use honey. It should NEVER be offered to infants less than a year old due to the risk of botulism.

Parents whose infants and toddlers experience problems with cow’s milk may want to try goat’s milk which is available in canned evaporated form. (There are commercial infant formulas made from goat’s milk.)

NO to Plant-based milks: plant-based milk products like soy or almond milk are NOT appropriate substitutes for commercial infant formula or breast milk. Their nutritional content is in no way similar.

WATER SAFETY: water used to prepare evaporated cow’s (or goat’s) milk formula must be sanitary — heated at a high enough temperature long enough to kill pathogens. Even when mixed with powered infant formula, water should be heated to 158 degrees Fahrenheit/70 degrees Celsius.

~ ~ ~

I’ve already seen lectures and scolding about breastfeeding being best along with more finger wagging about homemade formula because it’s not as healthy as ready-to-use infant formula or powdered infant formula.

To which I say refer back to the tweet thread by Phil Hernandez near the top of this post and look closely at the photos of the shelves taken in Norfolk VA. There’s exactly one breast milk bank listed for the entire state of Virginia and it’s in Norfolk as well.

What the hell are American parents with infants supposed to do when there’s not enough breast milk or commercial formula to go around?

Especially when the U.S. has plenty of evaporated cow’s milk on the shelves while producing too much cow’s milk altogether.

~ ~ ~

UPDATE-1 — 11:15 PM EDT —

Transportation Sec. Pete Buttigieg appeared on CBS’s Face the Nation this morning and was asked about the infant formula situation.

Transportation Sec. Buttigieg blames the nationwide baby formula shortage on the Abbott plant shutdown:

“It’s got to be safe and it’s got to be up and running as soon as possible. This is the difference between a supply-chain problem…and a supply problem.” pic.twitter.com/CuAvpKMQuB

— Face The Nation (@FaceTheNation) May 15, 2022

He nailed it when he says we have a capitalist system and the government doesn’t make formula. The right-wing has decided it wants to use this capitalist system failure as a means to attack the Biden administration, but the entire regulatory system has been constructed to serve corporations more so than the people who consume products (with the majority of corporations’ support going to the GOP and its candidates).

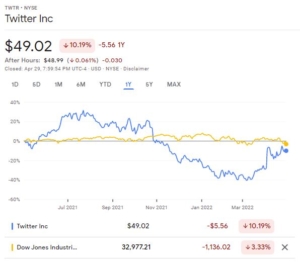

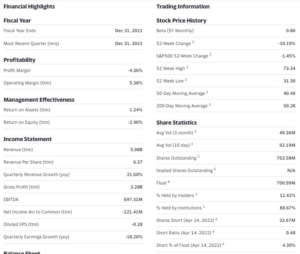

One only need look at OpenSecret’s data on Abbott Laboratories and Abbott Nutrition‘s campaign contribution history to both major parties to see part of the infant formula industry’s regulatory capture process at work.

The right-wing in this country needs to make up its mind: its political apparatus is either going to stand behind a free market, or more socialized government intervention when competition fails. It only seems to be settled on government getting the way overreaching into women’s uteruses and trans persons’ bathroom stalls and obstructing Black Americans’ access to the voting booth.

What’s particularly irritating about today’s Face the Nation segment is that Buttigieg isn’t the Commerce Secretary or the Health and Human Services Secretary, or the FDA Director.

He’s a concerned adoptive father who told CBS the infant formula situation “is very personal for us,” referring to his two nine-month-old infants.

But sure, let’s beat up on a parent who already has enough to worry about and isn’t responsible for the problem in his day job.

Creative commons

Creative commons