Working on another post, I went back and read all three Obama DNC speeches. (2004; 2008; 2012) Aside from the biographical details, several things remained constant through all three: the Hope theme (though it has evolved in interesting ways, which is what I was looking at), the inclusion of some version of “We don’t think the government can solve all our problems,” and a call for energy independence.

2004

In 2004, that call came in a list of things John Kerry planned to accomplish.

John Kerry believes in energy independence, so we aren’t held hostage to the profits of oil companies or the sabotage of foreign oil fields.

2008

In 2008, the call came with a specific goal: to end dependence on the Middle East by 2019.

And for the sake of our economy, our security, and the future of our planet, I will set a clear goal as President: in ten years, we will finally end our dependence on oil from the Middle East. [my emphasis]

Obama embodied the refusal of DC to address energy independence in John McCain’s career, and in the “Drill Baby Drill” chant that was the rage in political circles in 2008.

Washington’s been talking about our oil addiction for the last thirty years, and John McCain has been there for twenty-six of them. In that time, he’s said no to higher fuel-efficiency standards for cars, no to investments in renewable energy, no to renewable fuels. And today, we import triple the amount of oil as the day that Senator McCain took office.

Now is the time to end this addiction, and to understand that drilling is a stop-gap measure, not a long-term solution. Not even close.

And he made several promises–several of which he has made progress on, several of which he has thankfully not achieved, one of which–nukes–he has at least rhetorically dropped from his convention speech.

As President, I will tap our natural gas reserves, invest in clean coal technology, and find ways to safely harness nuclear power. I’ll help our auto companies re-tool, so that the fuel-efficient cars of the future are built right here in America. I’ll make it easier for the American people to afford these new cars. And I’ll invest 150 billion dollars over the next decade in affordable, renewable sources of energy – wind power and solar power and the next generation of biofuels; an investment that will lead to new industries and five million new jobs that pay well and can’t ever be outsourced.

2012

And last week he, correctly, argued that Mitt would not continue this commitment to an energy independence that relies on a range of sources (Mitt would certainly keep drilling, would expand traditional coal mining, and would keep paying Iowa farmers to pour corn into cars, but would probably not continued subsidies for clean technologies).

OBAMA: You can choose the path where we control more of our own energy. After thirty years of inaction, we raised fuel standards so that by the middle of the next decade, cars and trucks will go twice as far on a gallon of gas.

(APPLAUSE)

In this section, Obama quietly–too quietly–bragged about the jobs he created in battery and turbine plants.

We’ve doubled our use of renewable energy, and thousands of Americans have jobs today building wind turbines, and long-lasting batteries.

And he accurately claimed that these policies (plus the recession, plus a warm winter, though he doesn’t mention them) have made a difference.

In the last year alone, we cut oil imports by one million barrels a day, more than any administration in recent history. And today, the United States of America is less dependent on foreign oil than at any time in the last two decades.

(APPLAUSE)

So, now you have a choice – between a strategy that reverses this progress, or one that builds on it.

What I’m interested in, though, is the emphasis he places on the energy and the unconvincing nod he makes to climate change. In 2004, Obama had listed “the future of our planet” as the third of three reasons for his commitment to energy independence; the other two were “our economy” and “our security.” Here, an explicit admission that “climate change is not a hoax” comes among promises to “drill baby drill.”

We’ve opened millions of new acres for oil and gas exploration in the last three years, and we’ll open more. But unlike my opponent, I will not let oil companies write this country’s energy plan, or endanger our coastlines, or collect another $4 billion in corporate welfare from our taxpayers. We’re offering a better path. [my emphasis]

Even when I listened to this passage the other night, I was offended by his promise not to let oil companies endanger our coastlines. Oil from the BP spill came onshore with Hurricaine Isaac. Just a week before he delivered these lines, Obama approved Shell drilling in the Chukchi Sea which presents predictable dangers to coastlines and species, particularly given how Shell has already failed to take necessary precautions. And even the Saudis recognize that fracking presents a real threat to our groundwater. So not only is Obama not subordinating the sanctity of our coastlines to his commitment to drill, neither is he making adequate efforts to protect our drinking water.

(APPLAUSE)

We’re offering a better path, a future where we keep investing in wind and solar and clean coal; where farmers and scientists harness new biofuels to power our cars and trucks; where construction workers build homes and factories that waste less energy; where — where we develop a hundred year supply of natural gas that’s right beneath our feet.

If you choose this path, we can cut our oil imports in half by 2020 and support more than 600,000 new jobs in natural gas alone.

(APPLAUSE) [my emphasis]

Then, after what, given the brevity of the speech, is a very long section on drilling, Obama immediately nods to climate change.

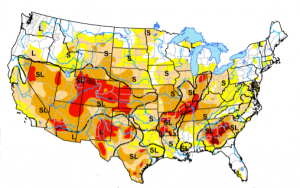

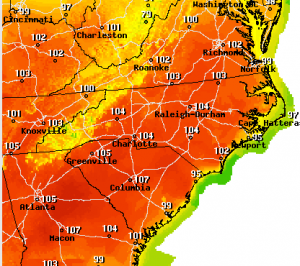

And yes, my plan will continue to reduce the carbon pollution that is heating our planet because climate change is not a hoax. More droughts and floods and wildfires are not a joke. They’re a threat to our children’s future. And in this election, you can do something about it. [my emphasis]

Now, the impact of shale oil on climate change is contentious issue. Because it currently replaces coal, it makes our total carbon release less damaging than it otherwise would be. But if you count up all the carbon in the shale gas that people plan to burn, planning to develop what is there it represents a huge threat to our climate. So while Obama’s claim that his plan–including the commitment to renewables–will reduce carbon pollution is not false, exactly, it’s not exactly preventing climate change.

Which is why I find Obama’s formulation on climate so interesting:

- Climate change is not a hoax

- More droughts and floods and wildfires are “a threat to our children’s future”

No! The droughts and floods and wildfires we already have are a threat to our present! They are a threat to our grand parents, parents, our own, and our children’s present, not some future time when most of us will be dead!

While this was one of the first and only mentions of climate change at the convention-easily one of the biggest threats facing our country, one which routinely kills more people than al Qaeda, which Obama claimed was our country’s greatest enemy–it spoke of climate change as a future threat, not an urgent present one, one which already blowing entire towns off the map.

This then, was not a promise to switch to fracking for the relatively lower carbon output it produces (particularly not with “clean” coal still in the speech). Rather, it was ancillary benefit of an energy independence pursued primarily for national and economic security reasons.

Don’t get me wrong. This is an area where Obama has substantially delivered on what he promised. As I’ve long said, the energy jobs Obama invested as part of the stimulus were incredibly important–certainly not as big a impact on jobs as the auto bailout, but more important to catching the US up on technologies we had grown dependent on other countries for (though between KORUS and China’s Wanxiang Group Corporation investment in A123, Obama’s not doing the things to sustain this effort). And they did create jobs Republicans around here have been claiming were due to raw entrepreneurship.

Further, as Michael Grunwald notes, Obama delivered $90 billion of the $150 billion promised back in 2008, with added private investment.

The energy stuff wasn’t just big, it was ginormous. It’s hard to get people twice as excited about $90 billion as they would be about $45 billion, or 10 times more than they would be about $9 billion, but even $9 billion would have been ginormous. Ten years earlier, [President] Clinton pushed a five-year, $6 billion clean energy bill that went nowhere; at the time it was seen as preposterous and unrealistic, and it was. And here, 10 years later, $90 billion in the guy’s first month in office. Plus it leveraged another $100 billion in private money.

Obama promised that he would double renewable power generation during his first term, and he did. In 2008, people had the sense that renewable energy was a tiny industry in the United States. What they forget is it was a tiny dead industry — because these wind and solar projects were essentially financed through tax credits, which required people with tax liability, and everybody had lost money, so nobody needed [the tax credits]. By changing those to a cash grant, it instantly unlocked this industry. Another thing that’s helped to create the wind and solar industry were advanced manufacturing tax credits, which were a gigantic deal. I think there were about 200 factories that got these credits.

Grunwald’s right that Obama should be boasting more about this.

I’d argue Obama should be likening them to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s security deal with the Saudis in 1945, which gave us the preferential access to oil that fueled our hegemonic growth since; Republican efforts to demonize these investments with the Solyndra scandal-mongering are effectively an effort to prevent Obama from making a similar kind of historical move on energy security that served as the foundation of American’s success for two generations.

All that said, in the 8 years since Obama’s been making these speeches, it has become increasingly clear that Obama’s understanding of energy’s relationship to security is badly outdated. To boast of more drilling while referring to climate change as a future problem is to misplace where the greatest security threats lie.

Obama (and before him and in even more mocking terms, Biden) made fun of Mitt for calling the Russians our biggest enemy.

My opponent and his running mate are new to foreign policy, but from all that we’ve seen and heard, they want to take us back to an era of blustering and blundering that cost America so dearly.

After all, you don’t call Russia our number one enemy, not Al Qaeda, Russia, unless you’re still stuck in a Cold War mind warp.

But he’s just as badly wrong as Mitt is when he says a handful of terrorists are a bigger threat than the climate-change related drought that shut down the Mississippi this summer. Even if this is all about security and economy–and not primarily climate change itself–when climate change ends up doing things al Qaeda never succeeded in doing (and certainly can’t do now), then Obama needs to rearrange his understanding of the priorities.