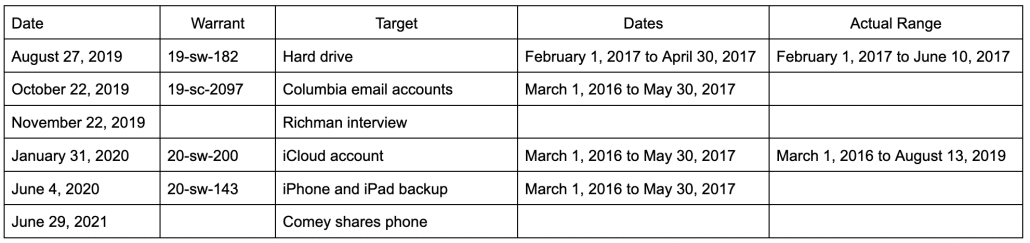

Did Lindsey Halligan sign and docket two indictments — nay, one indictment plus two copies (fucked and fixed) of a no-billed indictment?

“So this has never happened before. I’ve been handed two documents that are in the Mr. Comey case that are inconsistent with one another,” Vaala said to Halligan. “There seems to be a discrepancy. They’re both signed by the (grand jury) foreperson.”

And she noted that one document did not clearly indicate what the grand jury had decided.

“The one that says it’s a failure to concur in an indictment, it doesn’t say with respect to one count,” Vaala said. “It looks like they failed to concur across all three counts, so I’m a little confused as to why I was handed two things with the same case number that are inconsistent.”

Halligan initially responded that she hadn’t seen that version of the indictment.

“So I only reviewed the one with the two counts that our office redrafted when we found out about the two — two counts that were true billed, and I signed that one. I did not see the other one. I don’t know where that came from,” Halligan told the judge.

Vaala responded, “You didn’t see it?” And Halligan again told her, “I did not see that one.”

Vaala seemed surprised: “So your office didn’t prepare the indictment that they —”

Halligan then replied, “No, no, no — I — no, I prepared three counts. I only signed the one — the two-count (indictment). I don’t know which one with three counts you have in your hands.”

“Okay. It has your signature on it,” Vaala told Halligan, who responded, “Okay. Well.”

Except now that Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer can’t explain how she spent her day on September 25, Gabriel Diaz fronting for James Hayes under the name of Lindsey Halligan says maybe there wasn’t a second indictment.

The government’s position is that disclosure of grand jury materials is not warranted under the facts presented to the Magistrate Judge. Indeed, the government believes the Magistrate Judge may have misinterpreted some facts he found when issuing the latest order to release the grand jury materials to the defendant. For instance, (1) whether the defendant has any standing to challenge the Richman materials, (2) the full context of the statements made by the prosecutor to the grand jury, (3) that Agent-3 was exposed to potentially privileged material, and (4) that two indictments were presented to the grand jury. Additionally, the Magistrate Judge acknowledges he “did not immediately recognize any overtly privileged communications.” Dkt. No. 192 at 14. The possible exposure of privileged materials to the grand jury was the primary focus of the Magistrate Judge’s inquiry. Having seemingly settled that issue, the Magistrate Judge turns to premature issues such as suppression that have not even been briefed by the parties.

Literally items (2), (3), and (4) came from the government!

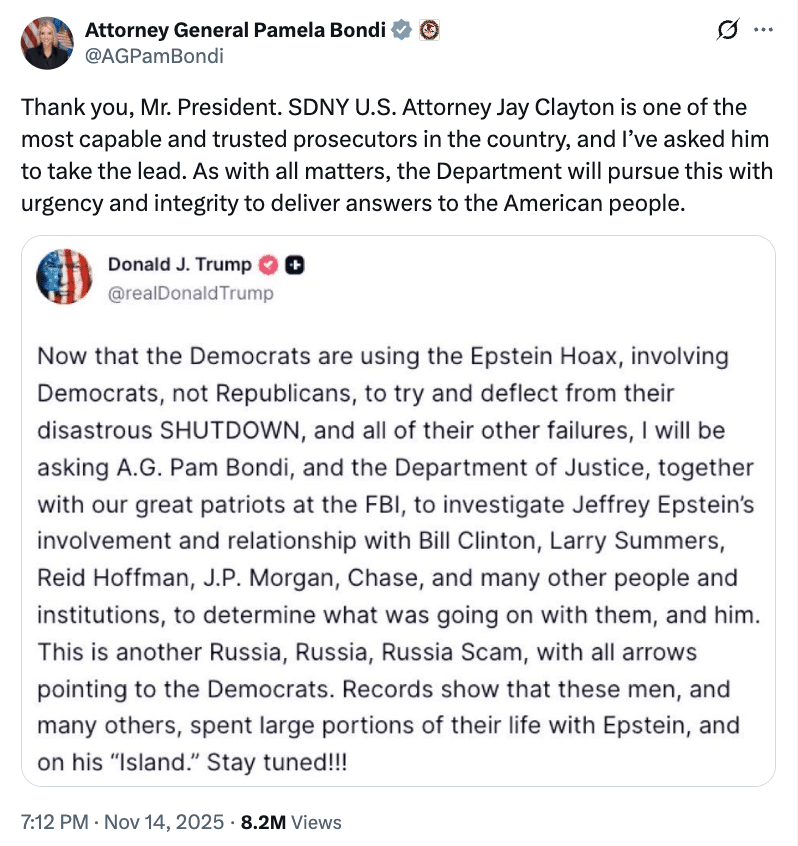

But now, in a desperate bid to buy a week of time to try to find a way to delay Jim Comey’s discovery that Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer and the Attorney General of the United States think he’s not entitled to Fifth Amendment rights.

If two indictments weren’t presented, then Lindsey the Insurance Lawyer has submitted a fabrication to the court and we should start criminal contempt proceedings.

Judge Fitzpatrick rattled off eleven problems with this indictment. And you want to stall for time?

All the evidence suggests there is no indictment, because the foreperson no-billed the only one presented to the grand jury.

And they want to stall for time?

Update: From Comey’s response. Holy hell these people are way more moderated than I would be.

Moreover, with respect to the presentment, the affidavit Ms. Halligan voluntarily presented raised significant concerns about whether the operative indictment was actually presented to the grand jury, and if so, by whom. The logical conclusion from Ms. Halligan’s declaration is that no one from the government presented a new indictment to the grand jury after it issued a no bill. Ms. Halligan’s declaration attests that she did not reappear before the grand jury upon learning of the grand jury’s vote to no bill the indictment she presented between 2:18PM and 4:28PM. See ECF No. 188-1 at 2 (“During the intermediary time, between concluding my presentation and being notified of the grand jury’s return, I had no interaction whatsoever with any members of the grand jury.”). And, importantly, she asserts that “the transcript accurately reflects the entirety of the government’s presentation and presence in front of the grand jury. There was no additional presentation, interaction, or discussion with the grand jury outside of what is reflected in the transcript.” ECF No. 188-1 at 1 (emphasis added). If no one from the government presented the operative indictment, as logically follows from Ms. Halligan’s own assertions and her ultimate handing up of a purported indictment that differs from the one partially no true billed, then the grand jury did not vote on it. See ECF No. 193 at 17-18.

Update: Here’s the colloquy between Magistrate Judge Lindsey Vaala and the Foreperson.

THE FOREPERSON: So the three counts should be just one count. It was the very first count that we did not agree on, and the Count Two and Three were then put in a different package, which we agreed on.

THE COURT: So you —

THE FOREPERSON: So they separated it.

THE COURT: Sorry, I didn’t mean to interrupt you. So you voted on the one that has the two counts?

THE FOREPERSON: Yes.

THE COURT: Okay. And you’re just giving me the other one for what reason?

THE FOREPERSON: That we could not agree on.

THE COURT: Okay. But just for one count?

Update: Judge Nachmanoff has given the government two days to bitch. Comey has a reply due on his broader grand jury request on Thursday, so Comey might file early.

ORDERED that the Motion (ECF 195) is GRANTED IN PART; and it is further ORDERED that the government will file any objections to Judge Fitzpatrick’s Order by 5:00 p.m. on Wednesday, November 19, 2025. Thereafter, the defense will file any response to any objection by the government by 5:00 p.m. on Friday, November 21, 2025; and it is further ORDERED that Judge Fitzpatrick’s Order (ECF 193) is STAYED pending the resolution of any objections filed by the government, which this Court will consider on the papers as to James B. Comey Jr. Signed by District Judge Michael S. Nachmanoff on 11/17/2025.

There’s also a hearing on Comey’s vindictive and selective prosecution on Wednesday.