A Tale of Three Capitol Visitor Center Arrests: Why January 6 Is Different from Portland

By the end of the month, all of six January 6 defendants who were arrested in the middle of the riot will almost certainly have pled guilty to misdemeanor trespassing offenses.

The four guilty pleas, thus far, have led me to realize how thin their statements of offense are as compared to others who have pled guilty, even those pleading to the same trespassing offense:

- Michael Curzio (July 12)

- Thomas Gallagher (July 15)

- Douglas Sweet (August 10)

- Cindy Fitchett (August 10)

The cornerstone to all these statements of offense is this paragraph describing how, shortly before 2:30 on January 6, after some Capitol Police officers told some rioters to leave and they didn’t, the officers started arresting people (the SOOs vary about whether the defendant claims not to have heard or, as with Curzio, admitted that he refused to leave).

10. Video surveillance depicted Sweet and Fitchett walking down a corridor in the Capitol Visitors Center, which is part of the Capitol building, shortly after 2:30 p.m., toward the end of the corridor area where U.S. Capitol Police officers had formed a defensive line. Other rioters also gathered in this corridor. The officers issued commands for the rioters to leave the building. Sweet maintains he did not hear those commands. When rioters refused their commands, the officers began arresting individuals who had unlawfully entered the building, including Sweet and Fitchett. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) uncovered no evidence that Sweet and Fitchett engaged in violent or disruptive conduct at the Capitol grounds or inside the building.

In Fitchett’s case, the government doesn’t even claim to know when she took a video of her approach to the Capitol with Sweet.

9. Sometime during the early afternoon of January 6, 2021, Fitchett recorded a video of herself and Sweet approaching an entrance into the Capitol with a large crowd around them yelling and making banging noises. Fitchett, with the camera turned on herself, stated in a raised voice, “We are storming the Capitol. We have broken in. Patriots arise.” Shortly after then, Sweet and Fitchett unlawfully entered the Capitol.

I find that interesting because these six arrests, almost alone of the the 560-some arrests so far, replicate a typical arrest from unrest in Portland where — according to a DOJ filing submitted in Garret Miller’s case last month — there’s just far less evidence with which to hold rioters accountable.

More fundamentally, the 45 Oregon cases serve as improper “comparator[s]” because those defendants and Miller are not similarly situated. Stone, 394 F. Supp. 3d at 31. Miller unlawfully entered the U.S. Capitol and resisted the law enforcement officers who tried to move him. Doc. 16, at 4. He did so while elected lawmakers and the Vice President of the United States were present in the building and attempting to certify the results of the 2020 Presidential Election in accordance with Article II of the Constitution. Id. at 2-3. And he committed a host of federal offenses attendant to this riot, including threatening to kill a Congresswoman and a USCP officer. Id. at 5-6. All this was captured on video and Miller’s social-media posts. See 4/1/21 Hr’g Tr. 19:14-15 (“[T]he evidence against Mr. Miller is strong.”). Contrast that with the 45 Oregon defendants, who—despite committing serious offenses—never entered the federal courthouse structure, impeded a congressional proceeding, or targeted a specific federal official or officer for assassination. Additionally, the government’s evidence in those cases often relied on officer recollections (e.g., identifying the particular offender on a darkened plaza with throngs of people) that could be challenged at trial—rather than video and well-documented incriminating statements available in this case. These situational and evidentiary differences represent “distinguishable legitimate prosecutorial factors that might justify making different prosecutorial decisions” in Miller’s case.

In fact, the affidavit used to arrest the six January 6 trespassing defendants shows that the Capitol Police officer who wrote it within a day of fighting rioters for what was likely hours, actually got the time of the arrest wrong by half an hour, an error which would have made it hard to charge felony obstruction if DOJ had considered it with these defendants.

In this context, at or about 3:00 p.m., I responded along with other members of the Capitol Police to a disturbance involving several dozen people who were inside the United States Capitol without lawful authority, under the circumstances described above. I observed the crowd moving together in a disorderly fashion, and I observed members of the crowd engage in conduct such as making loud noises, and kicking chairs, throwing an unknown liquid substance at officers, and spraying an unknown substance at officers.

In a loud and clear voice, Capitol Police Officers ordered the crowd to leave the building. The crowd did not comply, and instead responded by shouting and cursing at the Capitol Police Officers. I observed that the crowd, which at the time was located on the Upper Level of the United States Capitol Visitors Center near the door to the House Atrium, included the six individuals who were later identified to be Cindy Fitchett, Michael Curzio, Douglas Sweet, Terry Brown, Bradley Rukstales, and Thomas Gallgher. These six individuals were positioned towards the front of the crowd, close to the Capitol Police Officers who were responding, and to the officer who issued the order to leave. The six individuals, like others in the larger crowd, willfully refused the order to leave.

Even though they were caught on surveillance video, the Capitol Visitors Center was one of the least filmed places in the riot. To make things worse, Capitol Police Officers were not equipped with Body Worn Cameras that day, so there’s no record of this arrest.

In other words, for six people who entered the building, the FBI may have remarkably little evidence of their doing so, but because they alone among the thousands who did enter were arrested onsite and so were prosecuted.

It’s worth comparing those six arrests and resolution with the prosecutions of three others who were also in the Capitol Visitor’s Center at almost precisely that time, because it demonstrates how the FBI had so much other evidence covering the actions of most defendants.

First, there’s Robert Gieswein. He was arrested quite early in the investigation — on January 19 — based largely on his presence, kitted out in tactical gear and carrying a baseball bat, in some of the most spectacular scenes of the assault on the Capitol, including the initial breach with Dominic Pezzola.

But his initial arrest affidavit written ten days after the riot did not mention Gieswein’s actions inside the CVC at all.

That was only revealed in detention filing submitted in June. It revealed that, at about the same time and place where Curzio and others were being arrested, Gieswein was allegedly assaulting cops to avoid arrest.

Gieswein later went near the Capitol Visitor Center, where he and other rioters encountered a group of U.S. Capitol Police officers, and he again deployed his aerosol spray on those officers. Although there is not video of this incident that undersigned counsel is aware of, the defendant is charged with spraying and then assaulting a U.S. Capitol Police officer in the Capitol Visitor Center. According to that Officer, a person matching largely matching Gieswein’s description took out an unknown chemical-type aerosol agent, which one officer likened to OC spray, and sprayed a group of officers, causing irritation of the eyes. One officer recalls the person who matches the defendant’s description throwing punches at police. When the Capitol Police took the defendant to the ground to arrest him, other individuals around the defendant advanced on the officers, pushed them back, and freed Gieswein, who fled the area. Parts of the aftermath of this incident, including the defendant and Capitol police on the ground, and the defendant fleeing, are captured on Capitol surveillance video.

This is one of the rare assaults charged in January 6 of which there is not (yet, as far as we know) video evidence. If that were all Gieswein were arrested on — if he wasn’t also charged with assaulting two other sets of officers and obstruction — then his lawyers might be pushing to dismiss or plead down the charges, as happened with many Portland defendants.

But the rest of his actions were spectacularly caught on film, including this scene where he sprayed cops with some toxin.

In other words, in Gieswein’s case, police tried, but failed, to arrest him on January 6, probably along with the six who pled to misdemeanors. It took some days to track him down to Colorado and the FBI never recovered the clothes he wore or his phone. But even though he may have succeeded in hiding or destroying evidence he himself controlled, and even though one of his alleged assaults occurred in one of the few blind spots in the riot, there’s still a lot implicating him in the attack on the Capitol.

It took far longer to track down Jamie Buteau, along with his wife, Jennifer. They weren’t arrested until June 23, in Jamie’s case on charges of assault and civil disorder on top of trespassing.

At the moment everyone else discussed in this post was either being arrested or allegedly assaulting cops to avoid arrest, the Buteaus were nearby, with Jamie allegedly throwing chairs at cops on several occasions. As with Gieswein, there appears to be no Capitol CCTV of one of his assaults, one of several times he threw chairs, either. But a video posted to Parler captured him picking up a chair.

And while the closing doors hid Buteau at the moment he allegedly threw that chair (as the door also hid Gieswein’s face in the photo above), the Parler video captured the chair he had just been holding flying through the air.

By the time of their arrest, FBI had tracked the Buteaus from the moment they entered the Capitol at 2:25, to their presence at between the Crypt and CVC from 2:29 to 2:31, to their entry into the CVC just behind Gieswein, back through the Crypt at 2:44, and then out the South Door at 2:46.

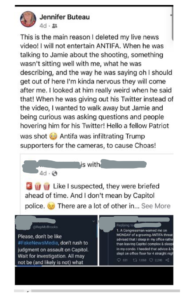

Like Gieswein, the Buteaus appear to have succeeded in destroying some evidence of their involvement in the riot. Jennifer was livestreaming onto Facebook the day of the riot, but she deleted that livestream and replaced it with a post blaming Antifa.

But several tipsters — including a former co-worker of another person with whom Buteau was at the riot — told the FBI about her live posts.

Jennifer also changed her Facebook profile to claim she was a Democrat, but one of her family members anonymously informed the FBI about that attempt to deceive — and also offered that both Buteaus had been in a HBO VICE show that another tipster (possibly one of the Sedition Trackers) found based off a BOLO picture showing Jamie’s face. Altogether, four different tipsters were able to provide the FBI information that the FBI (remarkably, in the case of the HBO appearance) wasn’t able to find on their own.

There were blind spots in the panopticon of the January 6 insurrection. But even defendants alleged to have committed assaults in one of those blind spots were still trackable by a slew of other evidence.

Ew,

Arrested while violently overthrowing the gov’t. Jan 6th trespassing inside Capitol building identifies you as obstructing congressional activities a federal crime. Sad when wagging appendage by one group of LE can’t respect another LE’s arrests as worthy of charging.

It would be interesting to see a Venn diagram showing the overlap of the defendants who deleted social media and messaging posts, vs those claiming “we thought they were welcoming us;” as well as one showing those who brought weapons of various types, vs those claiming they just got caught up in the spirit of the rally and the march. In both cases, it seems like the first condition is a clear rebuttal of the second.

A bit off topic, sorry, but the lawsuit against Walls-Kaufman and Taranto described in The Guardian isn’t discussed on this site?