Buried in DOJ’s Absolute Immunity Response, a Comment on Trump’s Suspected Zenith Crimes

Earlier this month, Trump’s DC team filed a motion to dismiss his January 6 indictment based on a claim of absolute immunity, an argument that Presidents cannot be prosecuted for things they did while President.

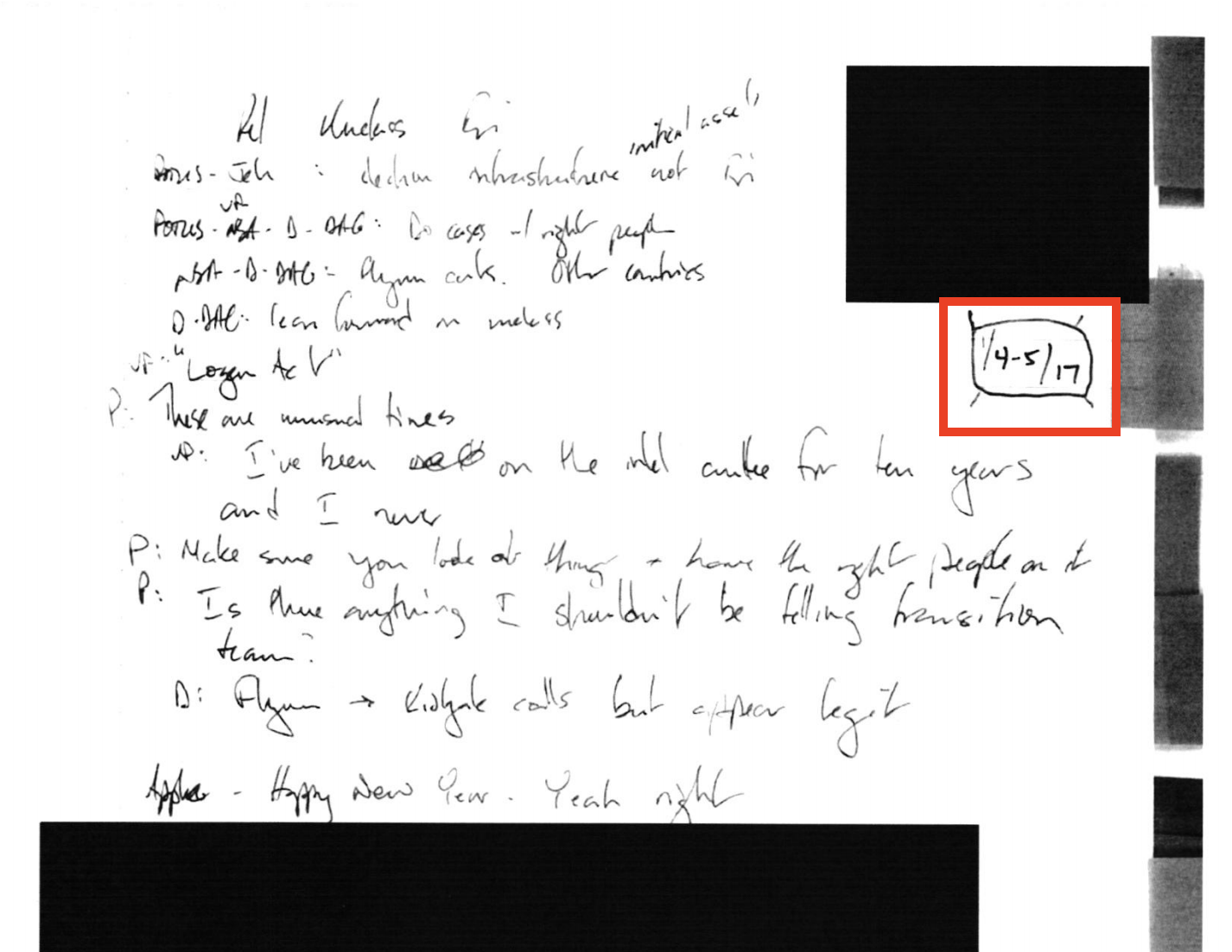

To get a sense of how shoddy Trump’s argument was, you need only compare the number of citations to these cases:

- Nixon v. Fitzgerald, which found Presidents had absolute immunity against civil lawsuits for things that fall within their official duties

- US v. Nixon, which found that the same President who had absolute immunity from civil suit could not use Executive Privilege to withhold evidence from a criminal prosecution

- Trump v. Vance, which held that Trump, while still President, was not immune from a criminal subpoena

- Thompson v. Trump, in which SCOTUS upheld a DC Circuit Opinion that upheld a Tanya Chutkan opinion that the events of January 6 overcame any Executive Privilege claim Trump might make to withhold documents from Congress, a far higher bar than withholding them from the FBI

Trump’s absolute immunity claim was a shoddy argument, but you never know what this SCOTUS would rubber stamp, even considering its cert denial in Thompson v. Trump and questions about whether Clarence Thomas (who did not recuse in that case, but did in John Eastman’s appeal of a crime-fraud ruling against him) would be shamed into recusing in this one.

Shoddy argument and all, there was never going to be a way to carry out the first-ever prosecution of a former President without defeating an absolute immunity claim.

In general, DOJ’s response is much more adequate than Trump’s motion to the task of laying out one side of an argument that will ultimately be decided by a very partisan Supreme Court. But it is written as the first response in what will be, whatever the outcome, a historic ruling.

Before it spends ten pages addressing Trump’s application of Nixon v. Fitzgerald, it spends ten pages laying out the constitutional framework in question. In a section addressing Trump’s claim that his impeachment acquittal on January 6 charges meant he could not be charged for related crimes, DOJ notes that Trump argued at the time, that as a former President, the Senate no longer had jurisdiction to hold an impeachment trial. Then it cites the many Republican Senators who used that stance to justify their own acquittal votes. It notes that the Nixon pardon and the Clinton settlement both presumed potential exposure to prosecution once they became former Presidents.

Out of necessity, the Fitzgerald section adopts an analogy from that precedent to this one: In the same way that Fitzgerald likened the President to prosecutors and judges who enjoy immunity for their official acts, Fitzgerald did not immunize those same prosecutors and judges from other crimes. At a time of increased focus on undeclared gifts that Clarence Thomas has accepted from people with matters before the court and after a Sam Alito interview — with someone who has matters before the court — in which he claimed separation of powers prohibited Congress from weighing in on SCOTUS ethics, DOJ cited the 11th Circuit opinion holding that then-Judge Alcee Hastings could be prosecuted. That is, whatever the outcome of this dispute, it may have implications for judges just as it will for Presidents.

Only after those lengthy sections does DOJ get into the specifics of this case, arguing:

- By misrepresenting the indictment in a bid to repackage it as acts that fit within the President’s official duties, Trump has not treated the allegations as true, as Motions To Dismiss must do

- Trump’s use of the Take Care Clause to claim the President’s official duties extend to Congress and the states is not backed by statute

- Because Trump is accused of conspiring with people outside of the government — unsurprisingly, DOJ ignores the Jeffrey Clark allegations in this passage (CC4), but while it invokes Rudy Giuliani (CC1), John Eastman (CC2), Kenneth Chesebro (CC5), and Boris Epshteyn (CC6), it is curiously silent about the allegations pertaining to Sidney Powell (CC3) — the case as a whole should not be dismissed

In total, DOJ’s more specific arguments take up just six pages of the response. I fear it does not do as much as it could do in distinguishing between the role of President and political candidate, something that will come before SCOTUS — and could get there first — in the civil suits against Trump.

And its commentary on Trump’s attempt to use the Take Care Clause to extend the President’s authority into areas reserved to the states and Congress is, in my opinion, too cursory.

The principal case on which the defendant relies (Mot. 35-36, 38, 43-44) for his expansive conception of the Take Care Clause, In re Neagle, 135 U.S. 1 (1890), cannot bear the weight of his arguments. In Neagle, the Supreme Court held that the Take Care Clause authorized the appointment of a deputy marshal to protect a Supreme Court Justice while traveling on circuit even in the absence of congressional authorization. Id. at 67-68; see Logan v. United States, 144 U.S. 263, 294 (1892) (describing Neagle’s holding); Youngstown Sheet & Tube, 343 U.S. at 661 n.3 (Clark, J., concurring) (same). Before reaching that conclusion, the Court in Neagle posed as a rhetorical question—which the defendant cites several times (Mot. 35, 38, 43, 44)—whether the president’s duty under the Take Care Clause is “limited to the enforcement of acts of congress or of treaties of the United States according to their express terms; or does it include the rights, duties, and obligations growing out of the constitution itself, our international relations, and all the protection implied by the nature of the government under the constitution?” 135 U.S. at 64. From the undisputed proposition that the president’s powers under Article II are not limited only to laws and treaties, it does not follow, as the defendant seems to imply, that every “right, duty, or obligation[]” under the Constitution is necessarily coterminous with the president’s powers under the Take Care Clause. Under that theory, for example, the president could superintend Congress’s constitutional obligation to keep a journal of its proceedings, U.S. Const. art. I, § 5, cl. 3, or the judiciary’s duty to adjudicate cases and controversies, U.S. Const. art. III, § 2, cl. 1.

The 11th Circuit and then SCOTUS will be facing a similar, albeit better argued, Take Care Clause argument when they review Mark Meadows’ bid to remove his Georgia prosecution. You’d think DOJ could do better — or at the very least note that Trump abdicated all premise of upholding the Take Care Clause during a crucial 187 minutes when his mob was attacking the Capitol.

All that said, I’m as interested in this response for the associated arguments — the seemingly hypothetical ones — such as the one (already noted) that in weighing this argument, the Supreme Court may also have to consider, again, whether they themselves are immune from prosecution for bribery.

It’s not just Clarence Thomas whose actions this fight could implicate.

In two places, DOJ uses hypotheticals to talk about other Presidential actions that might be crimes, rather than focus on the specifics of the case before Judge Chutkan.

For example, DOJ points to the possibility that a President might trade a pardon — a thing of value — as part of a quid pro quo to obtain false testimony or prevent true testimony.

For example, where a statute prohibits engaging in certain conduct for a corrupt purpose, the statute’s mens rea requirement tends to align, rather than conflict, with the president’s Article II duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed,” U.S. Const. art. II, § 3, which would weigh heavily against the need for immunity. To illustrate, although the president’s power to grant pardons is exclusive and not subject to congressional regulation, see United States v. Klein, 80 U.S. (13 Wall.) 128, 147-48 (1872), criminal immunity should not shield the corrupt use of a presidential pardon—which plainly constitutes “anything of value” for purposes of the federal bribery statute, see 18 U.S.C. § 201(b)(3)—to induce another person to testify falsely or not to testify at all in a judicial, congressional, or agency proceeding.

Less than five years ago, of course, Roger Stone was telegraphing that prosecutors had offered him leniency if he would testify about dozens of conversations that he had with Trump during the 2016 election. Less than five years ago, the newly cooperative Sidney Powell first asked Trump to hold off on pardoning Mike Flynn, only to welcome a Trump pardon of Flynn while Powell and Flynn plotted ways to steal the election. Less than five years ago, Trump gave a last minute pardon to Steve Bannon, who currently faces four months of prison time because he refused to testify to Congress.

I’m not saying DOJ will revisit these pardons, all of which fit squarely within such a quid pro quo description. I’m noting that if the argument as a whole survives, this part of it may also survive.

The same is true of an even splashier passage. A paragraph describing the implications of Trump’s claim to absolute immunity lays out what some commentators have taken as hyperbolic scenarios of presidential corruption.

The implications of the defendant’s unbounded immunity theory are startling. It would grant absolute immunity from criminal prosecution to a president who accepts a bribe in exchange for a lucrative government contract for a family member; a president who instructs his FBI Director to plant incriminating evidence on a political enemy; a president who orders the National Guard to murder his most prominent critics; or a president who sells nuclear secrets to a foreign adversary. After all, in each of these scenarios, the president could assert that he was simply executing the laws; or communicating with the Department of Justice; or discharging his powers as commander-in-chief; or engaging in foreign diplomacy—and his felonious purposes and motives, as the defendant repeatedly insists, would be completely irrelevant and could never even be aired at trial. In addition to the profoundly troubling implications for the rule of law and the inconsistency with the fundamental principle that no man is above the law, that novel approach to immunity in the criminal context, as explained above, has no basis in law or history.

These seemingly extreme cases of crimes a President might commit, crimes that everyone should agree would face prosecution, include (these are out of order):

- A President ordering the National Guard to murder his critics

- A President ordering an FBI agent to plant evidence on his political enemy

- A bribe paid in exchange for a family member getting a lucrative contract

- A President selling nuclear secrets to America’s adversaries

Like the pardon discussion above, these hypotheticals — as Commander-in-Chief, with the conduct of foreign policy, with the treatment of classified materials — invoke actions where DOJ typically argues that the President is at the zenith of his power.

We have no reason to believe that Trump ordered the National Guard, specifically, to murder his critics. But we do know that on January 3, 2021, Trump proposed calling out 10,000 members of the National Guard to “protect” his people and facilitate his own march on the Capitol.

And he just cut me off, and he goes, well, we should call in the National Guard.

And then I think it was Max who said something to the effect of, Well, we should only call in the Guard if we expect a problem. And then the President says, no, we should call in the Guard so that there aren’t – so that there isn’t a problem. You know, we need to make sure people are protected.

And he said – he looked over at Max, and I don’t know if somebody was standing behind him or not. He just looked the other way from me and says, you know, want to call in 10,000 National Guard. And then opened my folder and wrote down 10,000 National Guard, closed my folder again.

We know that days later Mark Meadows believed the Guard would be present and Proud Boy Charles Donohoe seemed to expect such protection.

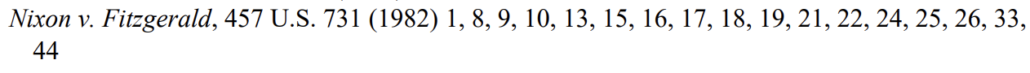

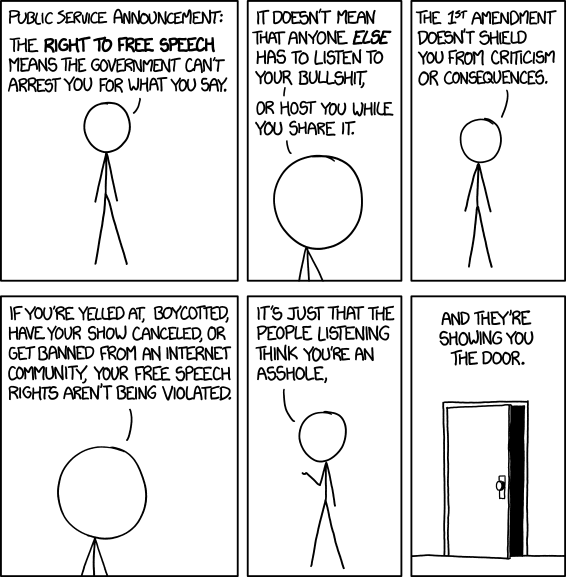

Similarly, we don’t know of a specific instance where Trump ordered an FBI agent to plant information on his political enemy. But we do know that as part of a Bill Barr-directed effort to reverse the Mike Flynn prosecution in 2020, misleading dates got added to the notes of Trump’s political enemies, Peter Strzok and Andrew McCabe.

Days after those misleading dates were made public via Sidney Powell, Trump used the misleading dates in a packaged debate attack on Joe Biden.

President Donald J. Trump: (01:02:22)

We’ve caught them all. We’ve got it all on tape. We’ve caught them all. And by the way, you gave the idea for the Logan Act against General Flynn. You better take a look at that, because we caught you in a sense, and President Obama was sitting in the office.

We know of no instance where Trump accepted a bribe in response to which a family member got a US government contract. We do, however, know of an instance where the Trump Administration gave the Saudis something of value — at the least, cover for the execution of Jamal Khashoggi — which everyone seems to believe has a tie to Jared’s lucrative $2 billion contract with the Saudi government.

As to selling nuclear secrets to a foreign adversary? Well, we know Trump had some number of nuclear secrets in his gaudy bathroom and then in his leatherbound box. We have no fucking clue what happened to the secrets that Walt Nauta allegedly withheld from Evan Corcoran’s review that got flown to Bedminster just before a Saudi golf tournament, never to be seen again.

All of which is to say that these edge cases — examples of Presidential misconduct that some commentators have treated as strictly hypothetical — all have near analogues in Trump’s record.

This response is a response about a very specific indictment, an indictment that describes actions Trump took as a candidate, often with those outside government, in ways that usurped the authorities reserved to states and Congress.

But in several points in the filing, DOJ invites review of other potential crimes, crimes conducted at the zenith of Presidential power, but crimes that may — must — otherwise be illegal, if no man is above the law.

Thank you. That litany of crimes, or analogous crimes, that Trump might have committed must have stirred a few otherwise heartless souls in Metro DC.

Well, I missed that. The other aspect to this could be that the list could just as well consist of “orders” Trump made that weren’t carried out.

Not to mention Ivanka’s Chinese trademark approvals.

[Welcome back to emptywheel. THIRD REQUEST: Please choose and use a unique username with a minimum of 8 letters. We are moving to a new minimum standard to support community security. Salting your existing name with a number might be an easy approach. Thanks. /~Rayne]

I’m not even sure SCOTUS will grant cert to a Trump absolute immunity case. By that time it will have been eviscerated by the DOJ, the district court, and almost certainly the appeals court. And to rule in Trump’s favor there will not fully guarantee the legal protection of an ex-president who has a strong chance of not winning again. But as importantly, using any national data calculator you’d like, within a decade Trump will be unable to personally participate in politics, and that number could end up being much smaller. Roberts, ACB, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh envision influencing court policy for two, maybe three decades. He’s not worth it.

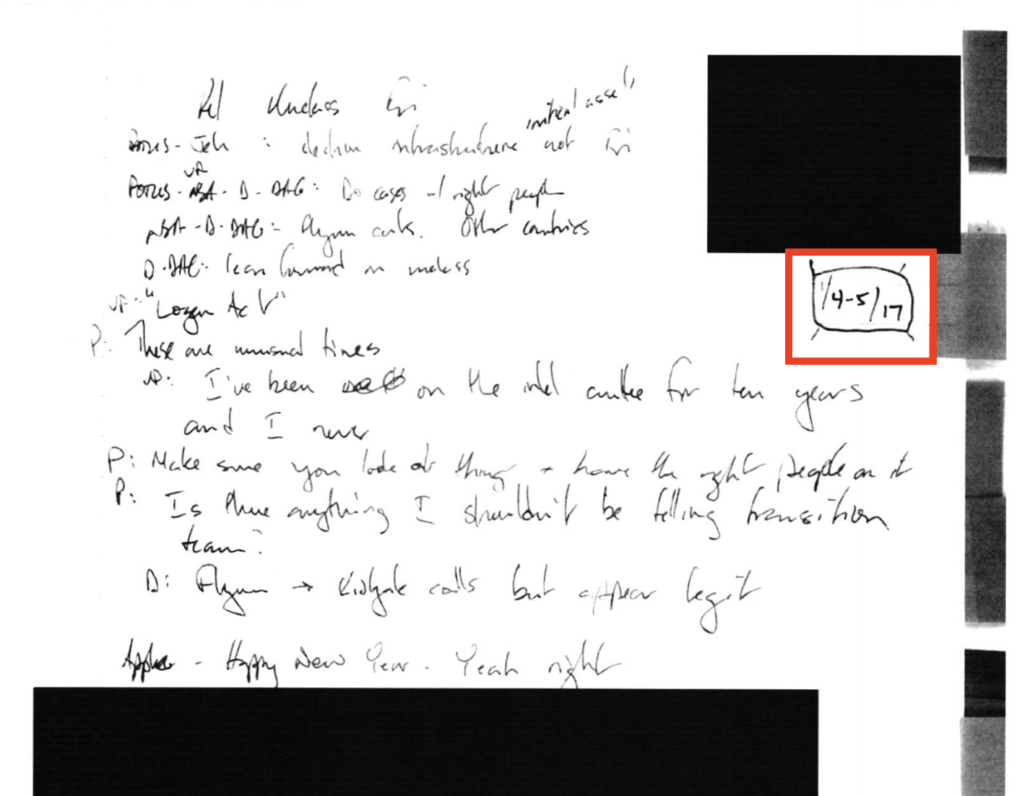

What is this site’s statute of limitations for derisive names for Trump? I don’t want my free speech to cause anyone to have another stroke.

You keep up this pointedly irritating bullshit and you will be gone. We do not have time for your crap.

First, I think it’s pretty clear that toying with Trump’s actual name is irritating to bmaz. Don’t do it.

Instead, if you must insult the former guy, at least use some grey matter to develop a nickname for that orange twat waffle.

Second, you have all the free speech rights you want, no one here is infringing them — get your own blog. Or go shit post on the dead bird app.

I saw a bumper sticker recently I’ve never seen before. It said:

Jesus Loves You.

Everyone else thinks you’re an asshole.

Lol.

For the record, I did not like “OBummer” and similar either.

Your consistency is not in doubt.

So I can’t call the rapist racketeer “Pussolini” but you can call me “asshole”.

Later.

If you picket, it won’t heal. . .

I wonder if I would get banned for using Don the Con as another name for Mr. Drump.

Stole money

Dodged draft

Cheated wives

Became President

The NEW American way.

You might. Are you so childish as to demand the right to use cheap slang when long requested not to? Is your life so full that THIS is the hill you want to die on? Please get a grip.

Also, too, this is not a poetry slam website.

It’s known as The Eric Cartman Principle. Most folks don’t like the hypocrisy of authoritarians, until they themselves become the authority. At that time, you must respect their authoritie.

As with murdering the English language, there is no statute of limitation.

And Westley said “We are men of action; lies and schoolyard bullying do not befit us.”

The inclusion of such pointed “hypotheticals” of crimes that a president might commit seems to have a purpose outside of the prosecution’s argument. There are innuendos here that seem to be very unusual in the context of an opposition to a motion to dismiss. Is the inclusion of these hypotheticals a warning to Trump that the DOJ has evidence of other criminality or that they are investigating other criminality? Using these hypotheticals calls to mind the federal evidentiary rule that where the probative value of evidence is outweighed by its prejudicial value, that evidence may be excluded. That rule however is directed towards jury trials (based on the fiction that judges can be trusted not to be confused or be unfairly influenced.) Using these hypotheticals appears to be a rather bold move for these upstanding prosecutors. This is not to say that it is improper; simply that it seems to be uncharacteristic.

I had same thoughts.

There’s only a small handful of legal proceedings I’ve followed in the past like I do all these (eg. ones Marcy follows closely). Of those (including Fitz), to me Smith has stood out as laser-beam focused, very clear purpose(s) and skilled using the law to fulfill them.

He stands out.

In my mind, I don’t just assume by consider it a given Smith have very clear purpose behind writing that stuff. At very least, its a shot-across-the-bow in that he’s not making specific accusations. But it is a loud shot, and I suspect it will be echoing for a good while to come.

That list of edge cases ought to make Trump very nervous, and likely very angry. Some commentators may treat them as strictly hypothetical, but Trump *knows* what he did. This reads to me as the DOJ sending a very strong message to Trump.

“We know what you did, though we have not charged you with these things. Maybe we don’t have the evidence lined up that can prove it in court. Maybe we don’t *want* to file these charges because we’d have to reveal things we’d rather not reveal. Or maybe we simply want to deal with this case before we file these other charges. So you’ve got to ask yourself one question: ‘Do I feel lucky?’ Well, do you, punk?”

This message will make him angry. And when Trump is angry, he makes bad decisions.

I can picture Trump’s legal team reading through this filing, then looking at each other across the table. “One of us has to ask him about these “hypotheticals,” so that we can prepare if there is something here that is not hypothetical after all.” I can’t imagine any of Trump’s lawyers volunteering to have that conversation with their client. I also can’t imaging Trump telling the truth to whatever lawyer comes to him for that conversation.

Lawyers here can correct me if I’m wrong, but a client who lies to their lawyer or withholds information from their lawyer isn’t going to get the best from that lawyer. Not because the lawyer wants to get back at the client, but because they can’t do their best if they don’t have all the facts.

Agreed that when the client doesn’t fully disclose it hampers the lawyer’s effectiveness. And could readily backfire.

Imagine arguing a matter to the court and trying to emphasize a point by distinguishing what is NOT involved—only to later find out the client withheld the information that the supposedly distinguishing fact IS involved.

Your client needs ESPECIALLY to tell you truthfully about the WORST parts. Then you go to work to put forward the best truthful version of whatever happened.

I too hear those “hypotheticals” as ominous for the Trump team.

Trading our nuclear technology isn’t hypothetical.

The Middle East Marshall Plan written by Tom Barrack on 3/10/17 spells it out very clearly.

The House Oversight Committee released a report on February 2019 that explains the Trump Administration’s repeated attempts to carry out the plan. “…whistle-blowers came forward to warn about efforts inside the White House to rush the transfer of highly sensitive U.S. nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia in potential violation of the Atomic Energy Act and without review by Congress as required by law–efforts that may be ongoing to this day.”

I’m surprised the media hasn’t revisited this report and the dire warning within it.

That message could be sent – maybe it has already been sent – to Trump and his lawyers without including it in a public filing, so it seems to have been included in this filing for public consumption and maybe even to suggest to the courts – as if they didn’t already know – that this is a very dangerous and corrupt defendant we are dealing with here.

Sending it in public makes it that much stronger for Trump and his lawyers. Speaking in private about non-hypothetical hypotheticals is pretty tame. Doing it in public carries with it a tone of “yes, we went there” for Trump.

If the goal is to goad him into making bad decisions, the goading needs to be in public. Goading in private is a one-time thing. Goading in public, where everyone can see it and news outlets notice it and talk about it, over and over again . . . it’s the goad that keeps on goading.

This super-deep dive into Coffee County is from August, off-topic, and requires a high count of coffees to get through, but I learned about it from a recent EW tweet, and it’s one of the most eye-opening Trump-crime-related revelations I’ve encountered [https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/what-the-heck-happened-in-coffee-county-georgia]. After reading it several times over several days, it casts the whole election-fraud conspiracy in a very different light. The Dominion stuff is a lot more like Q-Anon than I’d realized. Team Trump was crazy, but they were less crazy and more *lazy* than I’d imagined. By accepting a smaller-than-I-thought handful of lies and conspiracy theories, I can see how so many (from Fox News viewers to members of the Fulton County 19) actually started to believe the crazy stuff Sidney and Rudy were spinning. If you stubbornly ignore the obvious and immerse yourself in the suspicious red herrings, I can see how they bought the Dominion theories and temporarily began to believe and become outraged by the nonsense. It’s a perfect conspiracy theory because the biggest lies are camouflaged by the complexities of computer code. I think Sidney might not be crazy at all – just evil, and a clever would-be author of spy fiction. I keep thinking about that court document where she says something like “Wait – of *course* all this was obviously false – I never expected anyone to actually *believe* all that crazy stuff I said. No ‘reasonable person’ …”.

Yes. Written by the incredibly talented Anna Bowers, who went where others could have gone, had they had but the wit to do so. Great story.

“Anna Bowers, who went where others could have gone,…”

makes me speculate that certain journo-stenographers are or should be un-indicted co-conspirators in former president trump’s court cases!

Iirc, the ‘of course I didn’t believe this, nobody would’ was when she was trying to escape sanctions in MI. & that judge pinned Sidney & the rest of Team Kraken to the wall on all the unvetted garbage they included in their court filings

[Moderator’s note: You ignored the fourth and final warning about changing your username to comply with the site’s standards. Your comments will now go into auto-moderation until you change your name. /~Rayne]

When I read through the response, that paragraph really stood out for me. I found myself saying, “Wait a minute, didn’t he … ” and then trying to recall whether he’d actually, for example, sold nuclear secrets to an adversary,” and realizing that all the hypotheticals veered really close to actual behaviour. And yes, it did seem like a shot across the bows, as in, you’ve just asserted a bunch of bullshit, here’s some real shit to sup on, to read, reflect, and inwardly digest, as they say.

That would work with WilliamOckham’s hypothesis that these were “orders” that Trump gave that were not carried out. Smith may be able to prove that to be true based on testimony, emails, texts, etc.

But what does that mean in practical terms? What is the “shot across the bow”?

Is Smith threatening a superseding indictment?

Gotta leave a few scraps for the amici to snarl over.

Oh now that’s a plausible explanation.

Thanks!

IANAL, but why wouldn’t the DOJ keep it simple and use an exaggerated scenario to demonstrate the fallacy of presidential absolute immunity? For example, they could have posed the question: should a President have absolute immunity if they shoot someone dead? Instead, we get real or near-real hypotheticals that insinuate Trump is being charged with crimes that are not on the docket (at least not yet)! Maybe the DOJ is so focused on laying the groundwork for future prosecutions that they aren’t concerned that SCOTUS won’t rule in their favor on this one, but it seems like they’re introducing unnecessary risk by goading Thomas and Alito to narrow or reject their argument. Why not just focus on the task at hand.

Abby Normal, then. Why not keep it simple? At least two reasons, legal and rhetorical. Legally, as EW’s post points out, it’s more effective to use examples analogous to the crimes the defendant is suspected of having committed. It gets their goat, it reminds them that they might think they’ve gotten away with “it,” but reality might still hold them to account.

Rhetorically, no one remembers general statements not tied to known or suspected conduct by the defendant. But, everyone knows what you did last summer.

I never had the honor or arguing a Supreme Court case, but in the arguments I’ve read or heard, hypotheticals came up far more often than they did in my Circuit Court appellate arguments. The Justices often ask, “if you win/lose this point, how does it affect this related area?” So whether or not Smith’s team might be sending messages, they also seem to be trying to state the problems that ought to concern the Court. In a case that’s probably going up there, that could be a sensible approach.

I’m also not a lawyer, but see it like this. In the Introduction of the motion to dismiss, Trump’s lawyers say, “where, as here, the President’s actions are within the ambit of his office, he is absolutely immune from prosecution.” So it’s more effective for DOJ to give examples of crimes that are conceivably tied to the exercise of presidential powers. (Personally murdering someone would not be; giving orders to the National Guard to kill someone would.) Quoting DOJ’s response to the Trump motion:

JarDon Gate

JarDon Gate,

Wrought iron fate,

The case that’s never closed.

Spook the market,

Spook the target,

Spook the Holy Ghost.

In like Flynn,

Pretend to win,

Mask what was supposed.

Toss a Stone

to Prince alone:

A Bann on who will boast.

Watch for Mitch

to scratch the itch

of butts that he likes most.

Super-duper

Barr abuser

wormed into its host.

Investigate,

Subjugate,

Bet on who will coast.

Spook the market,

Spook the target,

Spook the Holy Ghost.

JarDon Gate,

Wrought iron fate,

The case that’s never closed.

Stole money

Dodged draft

Cheated wives

Became President

The NEW American Way

building his brand: Zenith, right up there with MAGAvox and RCA (Repugnant Constitution Abuser)

Lots of challenges dealing with an Apex traitor.

meanwhile Rs in Congress are WastingHouse

I’m pretty sure that in its McDonnell decision, SCOTUS indicated that members of the Judiciary are held to a higher standard than members of Congress when it comes to bribery.

Of course, that was 7 years ago. This court could decide that was a mistake.

Newsweek says Trump added a new lawyer to his DC legal team: https://www.newsweek.com/donald-trump-gets-new-attorney-1836428

Will Scharf was a holdover MI AUSA from Trump’s last year, and he also helped shepherd both Kavanaugh and Coney-Barrett through to confirmation, — and helped select ACB for nomination.

Oh, and he is (was?) running for MI AG

https://www.votescharf.com/

He tests kool-aid positive.

It’s not unreasonable to think that he was chosen in large part because he was instrumental in getting those two Justices their lifetime appointments, and they both know it.

You seem to think I was kidding. I am not. Slow your roll. There are limited people and resources here to keep track of gadabouts trying to consume our threads. Curb yourself, or be curbed by us. This is not hard.

Knowing this area of law a bit, I can dig in deeper later, but my quick take is DOJ may have had room to dance because Trump error (not treating non-movant’s assertions as true) means motion’s essentially dead. DOJ can beef up the officer vs. campaigner section when replying to Trump’s amended motion, assuming he files one. It’s difficult, and rarely productive, to refute arguments, or applications of law, based on “misstatements of fact” and claims made at “stratospheric level[s] of generality.”

The hypos, which would be the bulk of Oral Arguments on appeal, show Trump’s “rule” has no limiting principle, which SCOTUS institutionalists demand (Roberts, Comey Barrett, Kavanaugh). An additional tell who DOJ was arguing to, I think, is whose cited on page 33 — Bill Barr, Ted Olson, and Laurence Silberman (of the famed quote disparaging the FBI building being named after J. Edgar Hoover, its lawless-wiretapping, founding director: “the Federal Bureau of Investigation would be well served if his name were removed from the bureau’s building. It is as if the Defense Department were named for Aaron Burr.”)

Also, perhaps a stretch, but given SCOTUS’s propensity to overturn cases where the offender was not clearly put on notice (e.g., 11th Cir’s Lanier), including several some with high profile politician defendants, and there being plenty of upcoming time for Trump to crime again before trial, the hypos put Trump on notice that acts he could conceivably contemplate committing are indeed illegal, even when HE does them.

In the world of poker, the examples cited by the DOJ serve as big assed tells. If the DOJ has that evidence, the defendants have decades of personal freedom on the line and need to seriously consider stepping up for a plea deal.

Thanks for helping sort out this thorny topic. Not being an attorney, I don’t pretend to understand all of the nuances of the absolute immunity arguments at a meta level. However, just employing simple logic, a sitting president who misuses the powers of his office (e.g. calling a Secretary of State to persuade him to “find” votes that don’t exist) has to be a prosecutable crime, irrespective of immunity, because the intent was to retain the office from which the crime emanated. I guess it goes without saying, that f SCOTUS rules in Trump’s favor on this one, we are in Constitutional crisis territory! BTW – the tidbit about the nuclear secrets Walt Nauta may have shuttled to Bedminster and Trump may have sold to the Saudis, is extremely juicy! Can’t wait to read more! TY