The Cuellar Indictment: DOJ Moves to Make 219 FARA a Thing

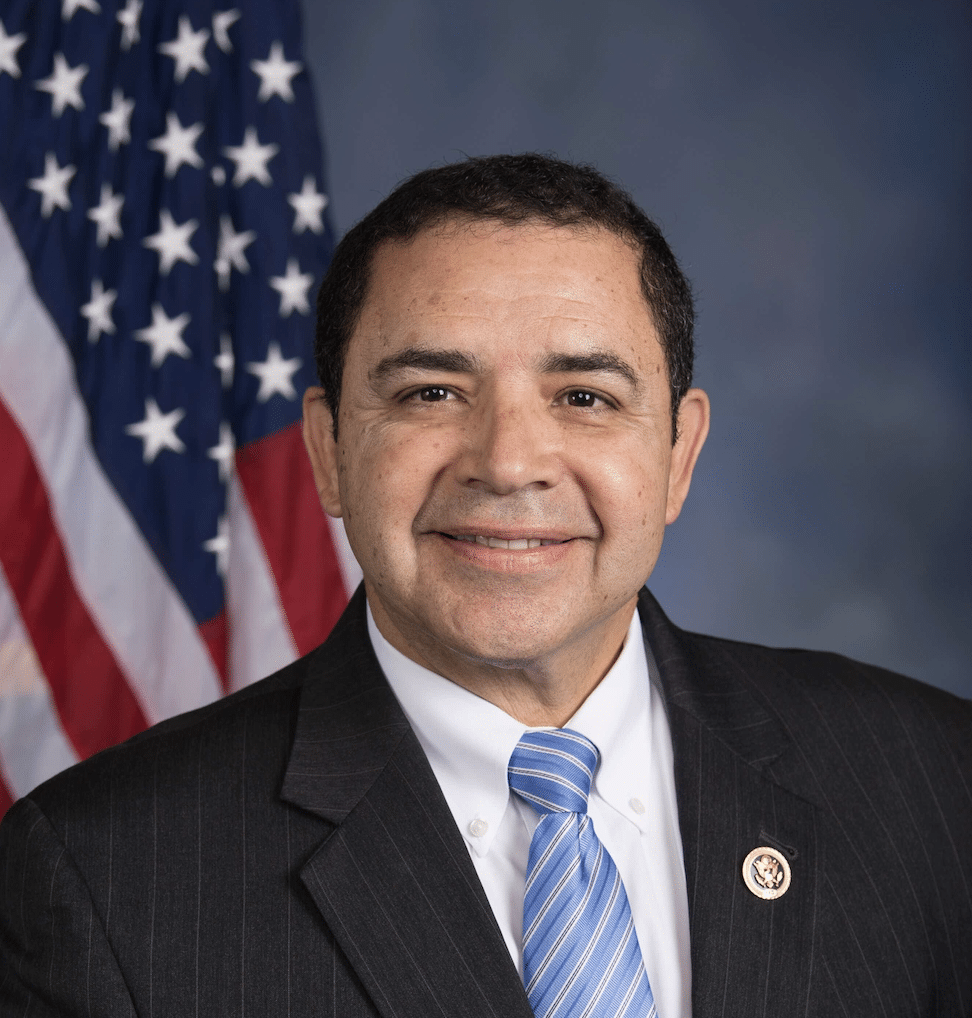

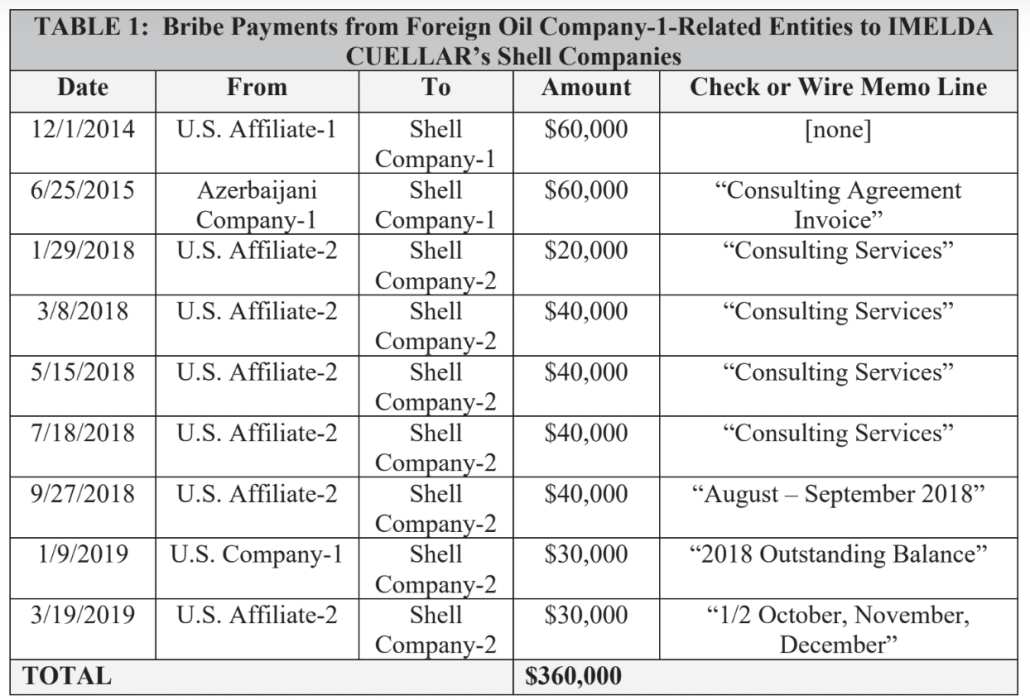

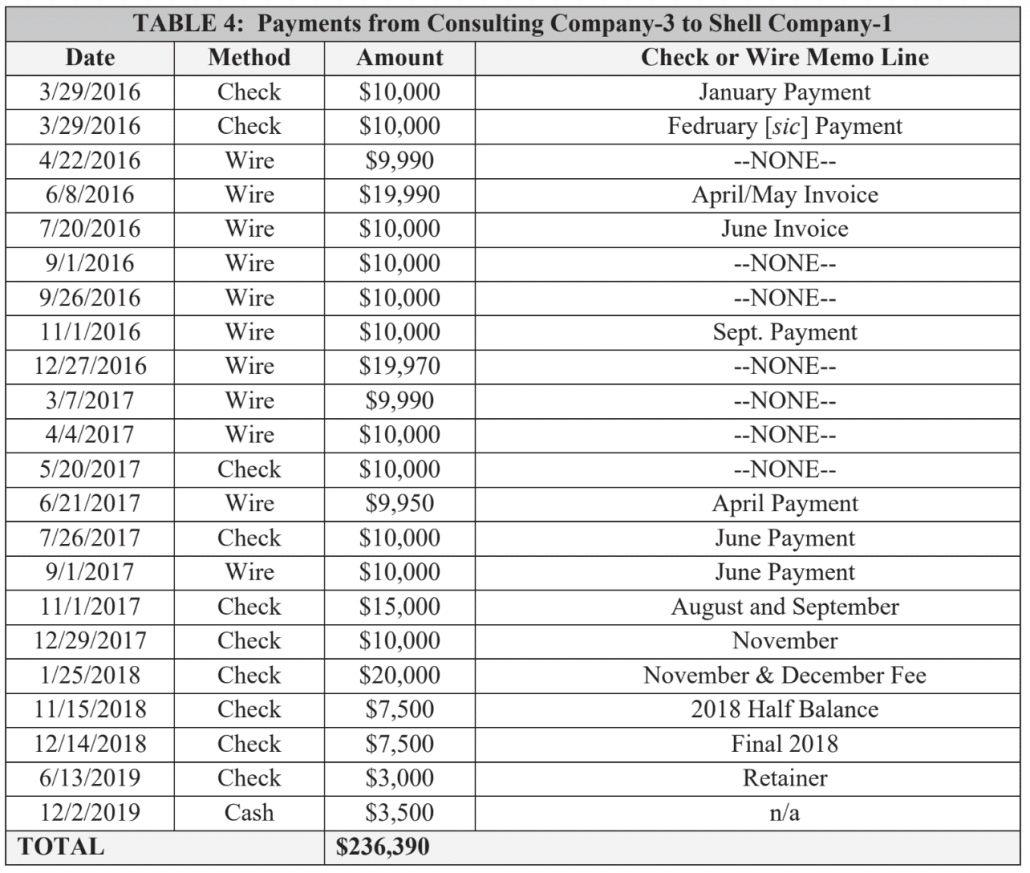

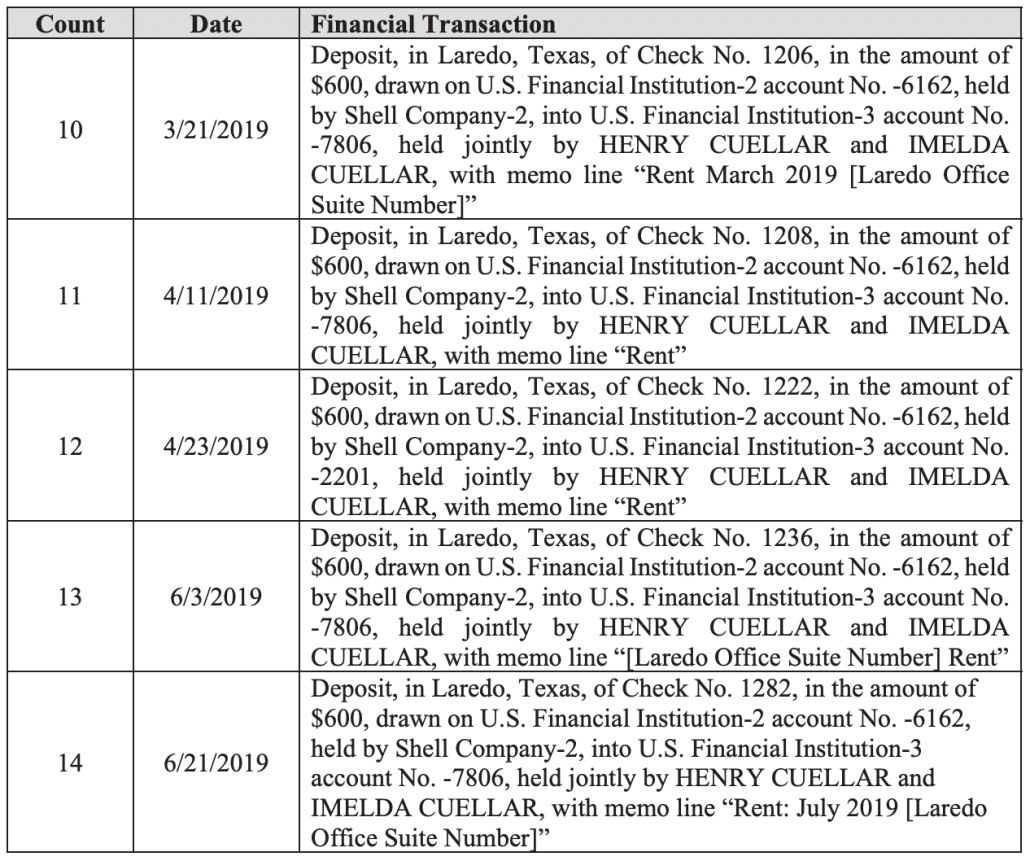

DOJ indicted Henry Cuellar and his spouse Imelda last Monday on charges that they laundered almost $600K in bribes through sham consulting contracts to Imelda in return for policies favorable to a state-owned Azerbaijani oil company and a Mexican bank.

The case was charged in South Texas, but will be prosecuted by a bunch of DC-based prosecutors.

Acting Deputy Chief Marco A. Palmieri, Acting Deputy Chief Rosaleen O’Gara, and Trial Attorney Celia Choy of the Criminal Division’s Public Integrity Section and Trial Attorney Garrett Coyle of the National Security Division’s Counterintelligence and Export Control Section are prosecuting the case.

There are two cases related to this one, 4:24-cr-00089, 4:24-cr-00113, both of which were charged this year, both of which remain sealed. That means several other people involved in this scheme are also being prosecuted.

There are several key participants in this alleged scheme who might be candidates for either parallel prosecution or cooperation deals. For example, one of the Cuellars’ adult children has allegedly been getting a cut of these deals and, in 2021 (both schemes appear to have paused in 2020), took over the Azerbaijani scheme and got payments to close out the Mexican scheme. As noted below, absent that child’s involvement, at least the Azerbaijani side of the indictment would face timeliness problems.

The indictment also describes that a San Antonio associate of Cuellar’s served as middleman for the contract with Mexico, allegedly laundered through Cuellar’s former Chief of Staff; three paragraphs of the indictment describe conversations the San Antonio associate had with Cuellar back in 2015 that must arise from his direct testimony.

The alleged conduct in this indictment is dated. The Azerbaijani side started over a decade ago, after Cuellar was elevated to Appropriations shortly after the couple traveled to Baku.

22. Shortly after the CUELLARS returned to the United States, Azerbaijani officials discussed recruiting HENRY CUELLAR to promote Azerbaijan’s interests in the United States Congress. On January 23, 2013, an Azerbaijani diplomat emailed the director of Foreign Oil Company-1’s Washington, D.C. office, listing the newly announced membership of the Appropriations Committee’s Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, which included HENRY CUELLAR. The diplomat wrote, “[t]he good news is that Cuellar was just in Baku.” The employee continued, “[w]e need to work with these offices to make sure we build an anti-[Representative-1] coalition.” Representative-1 was a member of the Congressional Armenian Caucus. The diplomat further wrote, “[i]n your Congressional outreach and engagement with [Individual-1] please keep in mind these folks as a top priority.”

The indictment alleges that by February of 2014, the Cuellars were setting up a consulting contract to receive funds.

Because these are dated allegations, there could be some vulnerability regarding statutes of limitation. For example, all the Azerbaijani payments to Imelda’s allegedly sham companies were more than five years ago.

All but two of the payments from Mexico to Imelda ended more than five years ago (and the Mexican side of the payment took place in January 2019, so outside that five years).

Three of the five individual money laundering charges happened more than five years ago — but just barely, a matter of weeks.

The couple’s child assumed — or perhaps resumed — the Azerbaijani relationship, but in 2021 (and specific details of payments are not provided). Three of 13 overt acts described as the payoff for bribes took place in 2020, when the indictment provides no evidence of payment (and the rest are all also more than five years old).

The same child was paid by the San Antonio associate the remainder of Mexican money owed in 2021.

So without including the child, this indictment would be barely viable, perhaps not viable at all with regards the Azerbaijani conduct.

The Cuellars are charged with a bunch of crimes: For both sides of the indictment, with conspiracy, bribery, and wire fraud, plus money laundering and money laundering conspiracy.

In addition, they’re charged with 18 USC 219 and 2, a public official acting as an agent of a foreign entity.

This is a FARA charge that was first used with Robert Menendez last year.

After his indictment was superseded a second time, he took to the Senate floor to describe how he has balanced criticism with support for the countries alleged to have bribed him, what he called diplomacy. He also argued that the government was trying to criminalize working to bring foreign contracts to New Jersey, something members of Congress do all the time.

But Menendez specifically took aim at that statute, 18 USC 219.

This is an unprecedented allegation. And it has never, ever been levied against a sitting member of Congress. Never. And for good reason.

It opens a dangerous door for the Justice Department to take the normal engagement of members of Congress with a foreign government and to transform those engagements into a charge of being a foreign agent for that government.

I want to address the accusations as they relate to me, but I don’t want you to lose sight of how dangerous this precedent will be to all of you. Let me start by describing my history of taking adverse positions to the government of Egypt. My defense of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law in that country, and my stinging criticism of the violation of human rights, democracy, and rule of law issues in Egypt. One fact is indisputable. Throughout my time in Congress, I have remained steadfast on the side of civil society and human rights defenders in Egypt and everywhere else in the world.

[snip]

Does any of this sound like I was on the take with Egypt? Of course not.

[snip]

But you can’t challenge the leader of an authoritarian state in public and among other members of Congress and take actions adverse to their interests and at the same time serve as an agent of that same foreign government.

Over my 30 years in engaging in foreign policy, I don’t know of any dictator or authoritarian leader who is willing to be publicly chastised, or regards someone who dares to do so, as his agent.

Which brings me to the danger of what the Justice Department has created by charging a sitting member of Congress with acting as a foreign agent.

The relevant FARA statute’s definition of agent is broad. It includes anyone who engages in political activities, publicity services, or other certain acts at the order, the request, or at the direction or control of an agent of a foreign principal. Applied to members of Congress, it covers anything that could in any way influence any official or agency of the United States or any section of the public within the United States as to public policy.

So, when members of the Senate from agricultural states went to Communist Cuba to sell rice or poultry or sugar or beef, and were told by the Castro regime they would consider doing so, but the Senators had to convince the US Administration to change US law and lift the embargo and permit credit to take place for such sales, and then came back to the United States and advocated for exactly that request, would that make them a foreign agent of Cuba? I think not.

[Reviews advocating for Iron Dome after a trip to Israel, advocating for Abraham Accords and civilian nuclear program and technology transfers after a trip to Saudi Arabia]

For the government, the sky is the limit if they want to pursue you.

Menendez went on to claim that DOJ’s allegations of giving of cash and gold bars were sensationalized, and that he would explain the real source of them.

It is a fair point, that often members of Congress will advocate for policies that either benefit their states or seem like sound policy even as those same policies may benefit a foreign power.

That said, Menendez did not, here, address the allegation that he gave sensitive information to Egypt and he spun his advocacy for Wael Hana to retain the halal contract for Egypt as someone protecting business in his district.

But he is right that, thus far, the government has not directly tied the cash and gold bars to specific official acts (and its claims about the purpose of the gold bars has evolved with each superseding indictment).

At least on their face, however, the allegations against Cuellar are more straightforward than those against Menendez, because in Cuellar’s case, there were contracts and efforts to create middlemen, contracts that Cuellar reviewed personally. A lot will depend, in the Cuellar case, on the government’s proof that Imelda did nothing in exchange for her contracts, something of which the government is only beginning to provide proof in the Menendez case (and because Menendez’ spouse Nadine is facing some kind of health crisis, she has been severed from the other defendants; her conduct will be presented as second-hand proof when the Menendez trial starts next week).

Menendez challenged the 219 charge against him, arguing that it put a jury in charge of evaluating advocacy that (Menendez argued) should be protected under Speech and Debate. In his challenge Menendez showed how quickly certain stances — advocating for the end to the embargo on Cuba, doing whatever Bibi Netanyahu asks, or funding Ukraine — could become retaliatory cudgels.

It is hard to imagine a criminal prosecution that is more flatly foreclosed by the Speech or Debate Clause.

To appreciate why, some background on FARA is needed. For most Americans, FARA is a disclosure statute: It requires those who meet its definition of “agent of a foreign principal” to register with the Department of Justice. FARA works differently for “public officials,” however, including “Member[s] of Congress.” 18 U.S.C. § 219(c). For them, FARA is not a disclosure obligation, but a criminal prohibition; it is a felony if any public official “is or acts” as an agent of a foreign principal. Id. § 219(a).

As to Members of Congress, the FARA analysis therefore turns exclusively on whether the legislator has acted as a foreign agent. And the definition of “agent” is broad: It includes anyone who (i) engages in “political activities,” “publicity” services, or certain other acts, (ii) “at the order, request, or under the direction or control, of a foreign principal.” 22 U.S.C. § 611(c)(1). The first element sweeps in most of what legislators do: Political activities include anything that will “in any way influence” the government or the public with respect to “domestic or foreign policies” or “the political or public interests, policies, or relations of a government of a foreign country.” Id. § 611(o). The second element, moreover, is so far-reaching that not even a “common law agency” relationship is required to satisfy its terms. Att’y Gen. of U.S. v. Irish N. Aid Comm., 668 F.2d 159, 161 (2d Cir. 1982).

As these elements reflect, § 219 thus operates differently than bribery statutes. The latter proscribe corrupt agreements by public officials. That is why it is possible to prosecute Members of Congress for agreeing to sell legislative acts, without proving or otherwise calling into question those acts themselves. Brewster, 408 U.S. at 526. By contrast, FARA targets actions. See 18 U.S.C. § 219(a) (prohibiting “act[ing]” as agent of a foreign principal). And if those action are legislative in nature, they are immunized as Speech or Debate.

[snip]

The Speech or Debate Clause forecloses the FARA count in this case. But there is a more fundamental constitutional problem with applying § 219 to any Member of Congress—which is perhaps why this has never before been done. For the Executive Branch to accuse an Article I legislator of a crime based on the way he performs his constitutional duties is an affront to the separation of powers and an infringement on the First Amendment. One branch cannot superintend another, let alone its advocacy, without posing serious dangers to the proper functioning of our democracy.

[snip]

Indeed, it takes little imagination to see what winds the government is sowing. Suppose a senator comes back from Israel, and says he will support whatever aid Prime Minister Netanyahu seeks. When he does so, is that at the “order” or “request” of a foreign power? Does it matter whether he would vote that way anyway? Is this really a question for a jury at trial? Now layer on top the risk of selective prosecution. Envision a future President hostile to Ukraine. Under § 219, that President could prosecute any legislative thorn in his side by charging a FARA violation for having promoted military aid at the behest of President Zelenskyy. As this case reveals, an indictment alone wreaks enormous political damage. This threat would produce a deep chill across Congress, freezing the ability of legislators to execute their functions. That is incompatible with our constitutional structure.

Judge Sidney Stein rejected the argument, because Congress itself applied Section 219 to itself and because Section 219 does not limit any constitutional power of Congress.

Menendez moves to dismiss Count Four based on a separation of powers argument. His central claim is that Section 219 violates the Constitution’s separation of powers doctrine when applied to Members of Congress by “delegating to the Executive and Judiciary the power to supervise the daily functioning of the Legislative.” (ECF No. 176 at 41.) According to Menendez, FARA’s language is broad enough to encompass nearly all activities of the Legislative Branch, so long as those activities are at the “order” or “request” of a foreign principal. Therefore, Menendez continues, Section 219 effectively—and impermissibly—tasks the Executive Branch and the Judiciary with supervising and prosecuting the day-to-day activities of legislators. Menendez emphasizes that this creates a significant risk of abuse by the Executive. For example, if Section 219 is applicable to Members of Congress, “a President could prosecute any legislative thorn in his side by charging a FARA violation for having promoted military aid at the behest” of the President of Ukraine (ECF No. 176 at 40), or could prosecute “the House Speaker for advocating a standalone aid-to-Israel bill at the request of Prime Minister Netanyahu.” (ECF No. 187 at 39.) Menendez urges that, under Section 219, “the only thing standing between a Senator on the Foreign Relations Committee and federal prison is a jury finding that he listened to one of the many foreign ‘requests’ or ‘directions’ that he hears out all the time.” (ECF No. 187 at 36.) This supervision of Congress by the Executive Branch, he contends, violates the Constitution’s separation of powers.

However, it is Congress itself that enacted Section 219, and explicitly provided in that statute that it applies to its Members as follows: “For the purpose of this section, ‘public official’ means Member of Congress.” 18 U.S.C. § 219(c). In other words, Congress specifically decided that its Members should be prohibited from acting as foreign agents and, if they do, should be fined or imprisoned. Indeed, far from being “an affront to congressional autonomy” (ECF No. 187 at 39), the decision to impose criminal sanctions on its Members who act as foreign agents was an expression of congressional autonomy. Moreover, while Section 219 may create an opportunity for abuse by the Executive, that risk is substantially mitigated by the fact that the Legislative Branch is uniquely positioned to amend the statute and exempt Members of Congress if it so chooses.

[snip]

[A]s in Rose and Menendez, Congress here has passed a law with a certain requirement for its Members—not to act as agents of a foreign government—and has explicitly empowered the Executive Branch to enforce that prohibition. And, as in Rose and Myers, the risks that any congressional work will be impaired or of presidential abuse are significantly mitigated by the fact that Congress can always amend the statute if it so chooses. These cases strongly support the Government’s position that enforcement of Section 219 against a Member of Congress is not barred by the separation of powers doctrine.

Again, I think Menendez’ case is at least more amorphous than Cuellar’s. It is, for example, easier to see how Menendez took actions that would benefit a businessperson in his district, though even Cuellar will be able to arguing that Azerbaijan was a crucial partner in the war on terror and that easy banking with Mexico is critical to his Laredo constituents.

I’m not saying DOJ is wrong to crack down when the spouses of members of Congress take payments from foreign countries directly affected by the policy choices their spouses make; they probably should be cracking down on such sham contracts more generally.

But DOJ is doing something new with these 219 prosecutions. We’ll see more clearly how that works in practice as Menendez goes on trial.

Third from last para, beginning with “Again”. Second clause of second sentence: “…even Cuellar will be able to arguing that Azerbaijan…”

Either “…even Cuellar could argue that…” or “…even Cuellar will argue that…” would work, former seems closer to what you intended overall.

I suspect that if Cuellar’s kid hadn’t gotten involved, this would have been ignored.

I would be much more sympathetic to Menendez’s argument about 219 if his spouse was not also charged for taking bribes. And that is also the common denominator with the Cuellar indictment but with his wife allleged to be more involved by way of acting as a contractor to launder the alleged payoffs.

Maybe the lesson here should be if you’re in Congress, do not include your family in your relationships with foreign governments especially if you’re taking some gratuities for your work.

(You’ve been taking well deserved weekends off of late, but I had a feeling you might be posting something about Cuellar after watching you yesterday on Nicole Sanders. That’s a great gig going on as I find it to be not only a good recap of what grabbed you in the week but you also indicate where your interests look to lie in the week ahead.)

Oh, I’m not eliciting sympathy for Menendez.

Just trying to take BOTH some shortcomings in the evidence against HIM seriously, but also his broader warning.

The role of the spouse is different in these two. At least from the available evidence, it looks like Nadine set up Menendez (after he was already charged with bribery once, it should be said). Whereas Cuellar was reviewing Imelda’s contracts before she finalized them.

Is there evidence that Nadine was setting Bob up, other than his own statement in his brief that was un-redacted a couple weeks ago?

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/bob-menendez-blame-wife-bribery-trial-unsealed-court-documents/

If not, this seems again like performative commentary by him, akin to what I mention below-thread.

I have suspected that from the start, and I’m not the only one. She had the pre-existing relationship with Hana, she managed the relationship with the Egyptians.

Still, that’s not necessarily indicative of “she completely pulled the wool over my eyes,” as his participation in the Halal scheme seems well documented, and especially when Uribe flips and cops to the Mercedes bribe, even though she organized those Egyptian interactions: he fully participated in it from what I’ve seen, even to the point of insisting with “Official-1” that the USDA stop opposing Halal’s halal monopoly he engineerd despite the harm it caused to US meat suppliers.

Also, the gold was logged into a theft investigation retrieval that Diabes signed off on as a victim back in 2013, not from Nadine’s mother’s estate, as they subsequently claimed — and Diabes’ prints are on some of the cash that was confiscated at the Menedez “dysfunction hoard” where the gold was found.

Bob’s complaint that this is a retribution indictment for the failed prosecution of his prior corruption case only holds water if these charges are bogus (e.g. if the prints were planted and/or “Official-1” is lying). It sure doesn’t smell that way to me.

It wouldn’t surprise me at all if Nadine offers to flip given her sub-bus positioning now. It also wouldn’t surprise me if the gov’t were to be very wary of such a move.

Daibes’ prints on the money tells us what, exactly? When were those prints put there? Thus far we have no evidence DOJ knows.

And, again, their story about the gold bars has evolved. First it was Egypt. Then it was Qatar.

Are you implying if you’re the president, it’s ok to include your family in your relationships with foreign governments?

Oh my goodness no!

Maybe I should have added a /s after the gratuity comment.

I just thought it curious that despite the difference in the Cuellar and Menendez cases they do have a co-indicted spouse as a common denominator.

And I did not mention a president, although the legally dubious antics of Javanka speak for themselves.

Here’s a transcription error in Menendez’ Senate speech, I assume:

“Does any of this (sound) like I was on the take with Egypt? Of course not.”

If he is guilty as charged, those ‘criticisms’ of Egypt’s anti-democratic behaviors he’s referring to there can be seen as *strategic* commentary, to be used in just such a speech following just such a tight spot. And his further statement that any despot would not tolerate such commentary is ridiculous on its face, given the likelihood of an understanding in such a situation that such commentary would be necessary to shield a Congressperson-cum-rumunerated-agent.

I also noted yesterday that Menendez’ motion to allow a shrink to testify on his behalf about his Castro-escapee-cash-and-bullion-hoarding disorder is being contested by the prosecution. Interestingly, it’s a disorder that his lawyers say has been untreated all these years, yet they have a therapist lined up who can testify to the authenticity of the disorder after a few sessions.

Again, performative commentary by him could be the key to pulling that defense maneuver off as well.

https://newjerseymonitor.com/2024/05/03/intergenerational-trauma-drove-sen-menendez-to-stash-cash-at-home-attorneys-say/

It feels almost like an M.O., no?

TY. My fingers are obviously not listening to what my braining is ordering them to do.

Q.E.D. [?] or was that on purpose? If so, LOL!

Heh, I assumed it was a *court* transcription error and that you cut and pasted the whole thing!

Oops, I meant Senate transcription, lol. Talk about brain-lock!

Family greed.

“The case was charged in South Texas, but will be prosecuted by a bunch of DC-based prosecutors.”

That’s always a risk in a place as mindfully local as South Texas.

Lol

A little like assigning a Thurgood Marshall to prosecute a South Texas lynching in 1960.

The decision seems self-harming, unless there’s a serious question of the local office being conflicted. But Shirley, the DoJ could have cobbled together a small team from nearby Southern states instead of apparently bigfooting a team from DC.

Shirley being my wife’s name, I have seen the movie “Airplane!” FAR too many times to let that one slide by without replying “and stop calling me Shirley!” …

Thank you for what was, for me, a Monday morning smile.

Isn’t FARA hard enough for prosecutors to get a conviction without trying to add new wrinkles?

Why is FARA so hard to convict anyway? Is it because it’s hard to prove beyond a reasonable doubt or does the jury just not fully have an understanding of the technicalities of the law? Or both?

Only the Tom Barrack case (a billionaire with some of the best lawyers in the country) was hard to prove.

Greg Craig’s case should never have been charged.

What makes normal FARA tricky is it’s a disclosure statute first. So prosecutors have to prove you knew of the disclosure and then falsified it.

219 is different tho, as Menendez says, in that it’s an outright criminal prohibition. We don’t yet know how that’ll fare at trial, which is one of the reasons I wrote this post.

Looks like it hinges on the bribery statute, if that fails, FARA falls also.

I got it now. Thanks for the response.

Maybe the time draws near for the DOJ to file against Ken Paxton (Texas AG) and DOJ decided to have Cuellar go first. If/when charges are filed against Paxton, there will be much complaining about weaponization of DOJ and targeting those of Trump World.

Having the Democrat Cuellar go first and then Paxton will show that DOJ isn’t going strictly against GOP. Still GOP/MAGA will ignore the Cuellar part and will complain.

There’s already ample evidence that the DoJ prosecutes Democrats as well as Republicans, but the GOP and its media mouthpieces will always come up with an excuse to discount it. With Cuellar, it’s that he’s a relatively conservative Democrat. With Menendez, it’s either that he’s very pro-Israel or that he’s been thrown under the bus by the ruthless Democrats/”Deep State” to discredit the notion of “weaponization” of DoJ against Trump. Everything that disproves rightwing conspiracy theories gets twisted into a way to prove those same conspiracy theories.

When corruption runs deep, the chief executive with the most dirt and least scruples can direct more power than they might otherwise. Maybe it’s better to charge some of these DP scowflaws now…before the griftiest of Presidential candidates closes on power again.

Her name is Imelda? Whoa, that brings back some bad vibes.

That seems like the key point for any of this – what congressfolk do has flooded far outside the banks of their constitutional powers and duties. I wonder how much of what Menendez considers his diplomatic duties (interacting directly with foreign governments) might be done more effectively by working with foreign governments through career diplomats.

At a minimum, that’s a career diplomat’s full-time job, and they are evaluated on that, rather than a congressperson being “evaluated” by their voters for their diplomatic work, mixed in with everything else the congressperson does.

More broadly, if we are ever to return to “partisanship stops at the US borders” dream we once had, having roughly 535 potential amateur diplomats piling in as independent actors doesn’t seem likely to help the US speak with one voice.

The awarding of a state monopoly to Hana’s company and its tentacles in the US connects Menendez to al-Sisi, one for whom the slogan “10% for the Big Guy” is not fake news and (allegedly) extends his and Egyptian state corruption into Congress.

“I don’t know of any dictator or authoritarian leader who is willing to be publicly chastised, or regards someone who dares to do so, as his agent.”

Maybe because they keep such relationships secret? It’s good cover and worth it if they can expect a greater benefit. Was that odd syntax which doesn’t quite say what you think it does intentional or just the result of extemporizing while guilty?