Citizenship

In the last part of Chapter 9 of The Origins Of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt explains her ideas about citizenship as a crucial part of human nature. Arendt was a scholar of the ancient Greeks, and it shows in this section.

A place in the world

In prior posts I looked at statelessness arising from the enormous European migrations during and after WWI. Millions of people were deprived of citizenship in their own nations, or worse, their nations disappeared, leaving them not even subject to deportation. Having no state to protect their rights, they were in effect deprived of all human rights.

The fundamental deprivation of human rights is manifested first and above all in the deprivation of a place in the world which makes opinions significant and actions effective. Something much more fundamental than freedom and justice, which are rights of citizens, is at stake when … one is placed in a situation where, unless he commits a crime, his treatment by others does not depend on what he does or does not do. P. 296.

In Arendt’s view, this is the nub of the disaster facing stateless people. They continue to exist, but it doesn’t matter what they say or think or do. They are alive, but they are useless, superfluous. Their treatment by others, the way they are dealt with by the state, has nothing to do with their opinions or actions.

This right, the right to participate in the life of a community, was thought to inhere in people. It has roots deep in human history and far back into pre-history. In earlier times, groups of people driven out of a community might be taken in by another group, or they might be able to live on their own, as shown in the delightful story of the Kimmeri as told by Herodotus in the Histories, Vol. 1, Book IV, ¶ 11 (set out below).

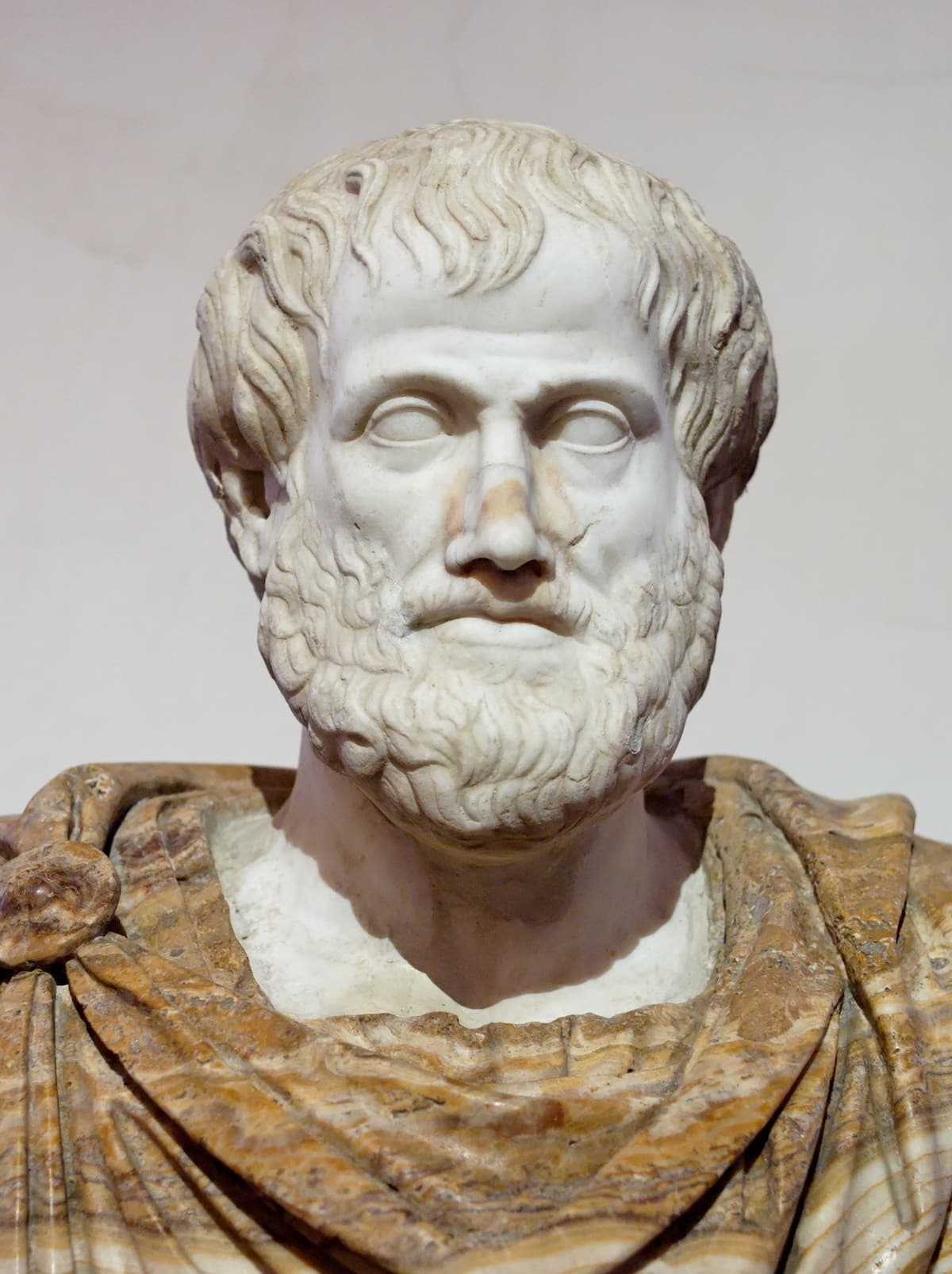

Arendt says that at least since Aristotle, the ability to speak and act was defined as the nature of human beings, and it was Aristotle who called humans “political animals”. Aristotle saw that these were not characteristics of slaves, and therefore slaves were not human. Arendt notes that even slaves had a place in society, and their labor was a valuable asset that remained in their control to some extent. But that wasn’t true of the stateless people. They had no place in society other than whatever charity might hand them.

In the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson says that the Colonies are entitled to “the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them”. In a passage based on the writings of Edmond Burke about the French Revolution, Arendt asks how we could possibly think a universe which showed no sign of either laws or rights implied anything for us humans.

A return to nationalism

Beginning at page 299, lay out Arendt offers her thought on the best way forward. The argument is multi-layered and not quite clear to me. As I read it, she thinks the solution can’t come from outside us, in history, nature, or from a common humanity. She thinks the solution lies in the laws of each nation. She thinks we are capable of creating laws that define and protect the rights we are willing to extend to each other, nation by nation.

She points to Burke’s rejection of the French Rights of Man And The Citizen. Burke calls these rights “abstractions”, and they are, just as Jefferson’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” are abstractions. We can’t govern ourselves with abstractions, we can’t protect abstractions, and we can’t even agree on the meaning of these abstractions because in the end, the meaning is dependent on the context.

According to Burke, the rights which we enjoy spring “from within the nation,” so that neither natural law, nor divine command, nor any concept of mankind such as Robespierre’s “human race,” “the sovereign of the earth,” are needed as a source of law. P. 299, fn. omitted.

She says:

We are not born equal; we become equal as members of a group on the strength of our decision to guarantee ourselves mutually equal rights. P. 301.

She offers a pragmatic justification: the abstractions failed the stateless, but the protection of rights by the state worked.

She offers more abstract justifications, based on the notion that we as humans deeply want to be part of societies, and to contribute our ideas and our labor to the general good. She notes that the ancient Greeks,distinguished between the public and private spaces in communal life. Private space is based on individuality and difference. Public life is based on equality of participation and recognition, and this is the sphere of life in which we all want to participate.

Discussion

1. The strength of our rights is based on our ability to work together to achieve a good life. Successful nation-states work to diminish or eliminate the kinds of differences, arising from the private space, that make working together difficult or impossible. Religion is often one of those intractable problems. In the US, the idea was to keep religion our of the public sphere to the maximum extent possible. We put it in the Constitution. In the 14th Amendment we said we wouldn’t deny rights to people on acount of race. Today we see how eroding that principles divides us, and makes solutions to common problems impossible.

2. I started this series saying that we humans create the rights of Man. Our ideas about how to live together have evolved over millennia as our human ancestors worked out ways of living together. Arendt says that the universe does not seem to recognize the categories of rights and laws (p. 298) so that we, who are part of nature, can’t deduce rights and laws about ourselves.

I don’t agree with that. We can and do deduce the actual laws governing nature, even laws we don’t understand, like quantum theory and dark matter. In a similar way, we can deduce laws that will give us the best chance of flourishing. This has already happened in the past when civilizations moved away from animism and paganism.

This transformation occurred independently in four different regions during the Axial Age, a pivotal period lasting from 900 B.C. to 200 B.C., producing Taoism and Confucianism in China, Buddhism and Hinduism in India, Judaism in the Middle East and philosophic rationalism in Greece.

This quote is from a review of a book by Karen Armstrong, The Great Transformation: The Beginning Of Our Religious Traditions, in the New York Times. As I recall this book, Armstrong sees a common strain in these religious traditions that can be summarized as forms of the Golden Rule.

Perhaps it was this common strain that led Enlightenment thinkers like Jefferson to the idea of natural rights, or universal rights recognized by everyone. Those universal rights were, of course, never actually universal: autocratic leaders found multiple reasons to deny them to groups of people.

Each of these great religions co-evolved with a different social structure. Those different structures have lasted several thousand years of material and intellectual changes. Are there signs that those structures are morphing towards greater commonality, at least among the wealthier citizens with access to the world-wide communications platforms? How would rights work in nations with a large number of people who have moved away from traditional structures while another large number remain committed to an older structure? Is there enough commonality among citizens to hold nations together?

========

The story of the Kimmerians, as told by Herodotus:

There is however also another story, which is as follows, and to this I am most inclined myself. It is to the effect that the nomad Scythians dwelling in Asia, being hard pressed in war by the Massagetai, left their abode and crossing the river Araxes came towards the Kimmerian land (for the land which now is occupied by the Scythians is said to have been in former times the land of the Kimmerians); and the Kimmerians, when the Scythians were coming against them, took counsel together, seeing that a great host was coming to fight against them; and it proved that their opinions were divided, both opinions being vehemently maintained, but the better being that of their kings: for the opinion of the people was that it was necessary to depart and that they ought not to run the risk of fighting against so many, 14 but that of the kings was to fight for their land with those who came against them: and as neither the people were willing by means to agree to the counsel of the kings nor the kings to that of the people, the people planned to depart without fighting and to deliver up the land to the invaders, while the kings resolved to die and to be laid in their own land, and not to flee with the mass of the people, considering the many goods of fortune which they had enjoyed, and the many evils which it might be supposed would come upon them, if they fled from their native land. Having resolved upon this, they parted into two bodies, and making their numbers equal they fought with one another: and when these had all been killed by one another’s hands, then the people of the Kimmerians buried them by the bank of the river Tyras (where their burial-place is still to be seen), and having buried them, then they made their way out from the land, and the Scythians when they came upon it found the land deserted of its inhabitants

I find it impossible to read about the “stateless” and not think of the Palestinians. (When I pause to reflect, the Rohingya also come to mind.) I assume I’m not alone in this.

How often does statelessness arise from people putting religion ahead of humanity (in a positive or negative sense)?

Almost always.

Very well written. Thank you

I don’t think highly of Hinduism or Buddhism as civilizing influences that are a great step forward. They both provide cosmic/religious support for the caste system, which isn’t so great if you aren’t near the top. It’s easy to talk about the spirituality of, e.g., Buddhism, but the social implications of “you are what you deserve to be, thanks to (my words) the Lords of Karma” are huge, the “divine right of kings” multiplied by 1.4 billion. I’ve seen and heard more and fiercer discrimination in the Indian subset of Silicon Valley over the last 40+ years than I ever saw growing up in Houston in the late ’60s and ’70s.

I am also reminded of the many stories, some collected in a book my mom has, about white women captured by Indians, and after a couple of years, not wanting to go back. I also note that plenty of preachers supported slavery in the South before the Civil War, although I am aware of the fact that many abolitionists came out of the Great Awakening as well.

I see a common strain in those religions of saying, “We are on top because an ultra-powerful being says it’s better that way, so suck it up and obey.” If you can get the oppressed to believe this, you have it made, but it doesn’t seem like the Golden Rule to me. Give me animism and paganism any day over the Judeo-Christian-Muslim religions and those of the Indian subcontinent.

Thank you, I’ve learned so much from your writing here. Today I think about 4 men who lost their lives working on a bridge in Baltimore. Who were they? Why were they there?

There hasn’t been nearly enough attention to the right’s efforts to strip citizenship from naturalized citizens and eliminate birthright citizenship.

It’s an obvious precursor to adding citizens to Trump’s immigrant roundups, but just as the press can’t accept the seriousness of that planned ethnic cleansing, they can’t accept how many of them would be affected if citizenship collapses.

There’s a notion that somehow this wouldn’t happen because of handwaving toward the Supreme Court and the Constitution. But in an autocracy the Supreme Court and the Constitution become what the autocrat says they are.

The current Supreme Court is so utterly corrupt that the idea that it would guard the liberty of anyone but a billionaire (preferably one that provided their pricey fishing trip or quarter of a million dollar RV is laughable.

A nation, like the Roman Empire may want to grant citizenship, but if the candidates don’t want it, they retain their intellectual and spiritual distinction. In the case of the Romans, Greek intellectuals, and the several outback areas surrounding the empire, never wanted to be Roman.

“Nothing which was being done, no matter how stupid, no matter how many people knew and foretold the consequences, could be undone or prevented. Every event had the finality of a last judgment, a judgment that was passed neither by God nor by the devil, but looked rather like the expression of some unredeemably stupid fatality” is a quote that is going to be bouncing around the back of my brain for some time. I need to find my paper copy of Totalitarianism, break out the highlighters, and go to town on the first two parts. I’ve read the third part, and it haunts me somewhat.

Statements like “total domination… is possible only if each and every person can be reduced to a never-changing identity of reactions, so that each of these bundles of reactions can be exchanged at random for any other” hit awfully close to home these days, especially considering the state of social media and modern (mis)information warfare.

I believe in universal birthright citizenship. That is, if you’ve been born, you have a right to be a citizen of any country. Sure, at birth, that would default to your mother’s choice. After that, anyone should be able to change their citizenship by a simple affirmation. No tests, no residency requirements, no limits whatsoever. If you think that would diminish the value of citizenship, think carefully about why. If citizenship derives its value from our ability to restrict it arbitrarily, the problem of statelessness is an evil we’ve chosen to impose on others that we’re unwilling to impose on ourselves. And that makes me wonder about our collective commitment to our supposed ideals.

If we truly believe in the Golden Rule, how can we deny others such a fundamental right?

You and John Lennon:

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-e&q=lyrics+to+lennon%27s+Imagin

Sorry, omitted the e

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-e&q=lyrics+to+John+Lenno%27s+imagine

Bag it.

Imagine there’s no heaven

It’s easy if you try

No hell below us

Above us, only sky

Imagine all the people

Livin’ for today

Ah

Imagine there’s no countries

It isn’t hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion, too

Imagine all the people

Livin’ life in peace

You

You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one

I hope someday you’ll join us

And the world will be as one

Imagine no possessions

I wonder if you can

No need for greed or hunger

A brotherhood of man

Imagine all the people

Sharing all the world

You

You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one

I hope someday you’ll join us

And the world will live as one

Let’s not do this again as it’s not Fair Use. I’m leaving it for now but do not copy-and-paste in entirety copyrighted material like this, especially without a full attribution to the artist and the distributor. In the age of the internet it’s simple to do the right thing, like this:

Songwriters: John Winston Lennon; Imagine lyrics © Budde Music France, CONSALAD CO., Ltd, Downtown Music Publishing, Sentric Music, Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, TuneCore Inc.