Mark Meadows’ Middling Path: There Are Several Paths to Prosecute Donald Trump

Two things happened over the weekend that may provide more clarity about Mark Meadows’ fate in the twin Trump investigations in which he’s implicated.

Second in terms of order but I’ll deal with it first, ABC had a big scoop about key parts of his testimony in the stolen documents case. There are four key disclosures about Meadows’ testimony.

- Meadows knew of no standing order to declassify documents

- He was not involved in packing boxes, didn’t see Trump doing so, and wasn’t aware Trump had taken classified documents

- Meadows offered to sort through boxes of documents after NARA inquired about them in May 2021, but Trump declined the offer

- Meadows ultimately backed his ghostwriter’s account that the Iran document that Trump described to Meadows’ ghost-writer was on the couch in front of him at the time of the exchange

The circumstances around Meadows’ testimony about his ghost-writer are the most telling. As ABC describes it, his ghost-writer sent him a draft that conflicted with the final copy of his book. That draft described that when Trump boasted about an Iran document he could use to prove Mark Milley wrong, it was in front of him on the couch. After receiving the draft, Meadows edited out the account that would provide proof Trump was sharing a classified document at Bedminster.

But a draft version of the passage initially sent to Meadows by his ghostwriter, which was reviewed by ABC News, more directly referenced the document allegedly in Trump’s possession during the interview.

“On the couch in front of the President’s desk, there’s a four-page report typed up by Mark Milley himself,” the draft reads. “It shows the general’s own plan to attack Iran, something he urged President Trump to do more than once during his presidency. … When President Trump found this plan in his old files this morning, he pointed out that if he had been able to make this declassified, it would probably ‘win his case.'”

Investigators may have found this by obtaining a warrant for Meadows’ email and discovering it as a clearly non-privileged attachment, by subpoenaing Meadows’ ghost writer, or both. It would be unsurprising if Jack Smith obtained Meadows’ email from 2020 through the FBI search of Mar-a-Lago, particularly given reports that his account got a privilege review too, and attachments are often the most interesting things obtained from cloud warrants.

The discrepancy between the draft and the final — hinting that Meadows recognized the document to be particularly sensitive — may have driven investigative focus on the document, leading Smith to obtain several recordings of the conversation and ultimately testimony sufficient to charge Trump’s willful retention of it in the superseding indictment.

Just as significantly, for a read of Meadows’ posture towards the dual investigations into Trump: ABC describes that his testimony changed. At some unspecified original interview (by context it appears to have been before the MAL search), Meadows said that he edited that passage because he didn’t believe it. But, apparently in that first interview, he conceded that if Trump did have the document in Bedminster to share with his ghost-writer, it would be problematic.

Sources told ABC News that Meadows was questioned by Smith’s investigators about the changes made to the language in the draft, and Meadows claimed, according to the sources, that he personally edited it out because he didn’t believe at the time that Trump would have possessed a document like that at Bedminster.

Meadows also said that if it were true Trump did indeed have such a document, it would be “problematic” and “concerning,” sources familiar with the exchange said.

But then Meadows’ own testimony changed — possibly at the April grand jury appearance mentioned by ABC.

Meadows said his perspective changed on whether his ghostwriter’s recollection could have been accurate, given the later revelations about the classified materials recovered from Mar-a-Lago in the months since his book was published, the sources said.

Meadows’ explanation for his changed testimony is not all that credible. It sounds like, as he came to understand how solid the case against Trump was, he became less interested in exposing himself to legal troubles by protecting him.

But for Meadows’ purposes, it likely doesn’t have to be. Meadows was not a direct witness to this incident. After prosecutors spent much of the spring fleshing out what happened here, it seems, Meadows conceded the points that were necessary. And the concession may well have been key to the inclusion of the document in the indictment(s): because it meant a witness who might otherwise have provided exculpatory testimony was locked into testimony that did not dispute the testimony of the direct witnesses against Trump.

Importantly, this is not the testimony of a cooperating witness. It is the testimony of someone prosecutors have coaxed to tell the truth by collecting so much evidence there’s no longer room to do otherwise. And it is testimony, if Meadows provided it at that April grand jury appearance, obtained four months after Fani Willis lost her grand jury as an investigative tool.

Which brings us to Meadows’ motion to dismiss the Georgia charges against him, submitted in federal court in NDGA.

The day after the GA indictment, Meadows’ attorneys filed to have it removed from GA to federal court because he was a senior government official during the events in question; this was expected from him, and still is expected from Trump and Jeffrey Clark. The next day, Judge Steve Jones ruled that he had to hear the challenge — effectively ruling that there was nothing procedurally wrong with Meadows’ demand.

Then Friday, Meadows’ team submitted their motion to dismiss the Georgia charges against him. Again, this was expected. But I also expected the brief to be far stronger than it is. It is an example where a team of superb lawyers argue the law — 19 pages of citations before they finally get around to addressing the alleged facts, and several more pages of law but not facts to follow.

Meadows’ motion makes three arguments about how the law applies to the alleged facts:

- Meadows’ alleged actions in the GA indictment fall within his duties as Chief of Staff

- But for his position as Chief of Staff which required him to remain close to provide advice, he would not have done the actions alleged

- His actions were legal at the federal level

The first two points are closely related and appear in two successive paragraphs. It is true that Meadows’ job was to arrange whatever calls the President wanted to make. And most — but not all — of Meadows’ alleged Georgia acts fit into that kind of thing.

The question is not whether Mr. Meadows was specifically authorized or required to do each act, but whether they fall within “the general scope of [his] duties.” Baucom, 677 F.2d at 1350. They surely do. As noted, those duties included information-gathering and providing close and confidential advice to the President. Moreover, as explained below, the State’s characterization of one of these acts as violating state law is wholly irrelevant. See Part II.B, infra. Stripped of the State’s gloss, the underlying facts entail duties with the core functions of a Chief of Staff to the President of the United States: arranging or attending Oval Office meetings, contacting state officials on the President’s behalf, visiting a state government building, and setting up a phone call for the President with a state official. Those activities have a plain connection to his official duties and to the federal policy reflected in establishing the White House Office. [my emphasis]

From there, Meadows argues that if he weren’t Chief of Staff to epic scofflaw Donald Trump, he wouldn’t have been doing these unlawful things for Donald Trump, and if he had simply left the room to object, then he wouldn’t be in the room to provide close and confidential advice.

The “nexus” is readily apparent. Only by virtue of his Chief of Staff role was Mr. Meadows involved in the conduct charged. Put another way, his federal position was a but-for cause of his alleged involvement. Moreover, if Mr. Meadows had absented himself from Oval Office meetings or refused to arrange meetings or calls between the President and governmental leaders, that would have affected his ability to provide the close and confidential advice that a Chief of Staff is supposed to provide. It is inescapable that the charged conduct arose from his duties and was material to the carrying out of his duties, providing more than merely “some nexus.”

Thus far (and ignoring that not all of the charged conduct in Georgia qualifies), this argument actually makes perfect sense for the removal and dismissal argument. Several of the actions charged against Meadows in Georgia really are about arranging meetings and phone calls for the President.

And the argument that Meadows had to stick around to provide advice is stronger than you might think.

It’s where Meadows’ team argues that his actions were legal at the federal level where, in my opinion, the argument starts to collapse — but also where this filing hints at more about Meadows’ strategy for avoiding charges himself.

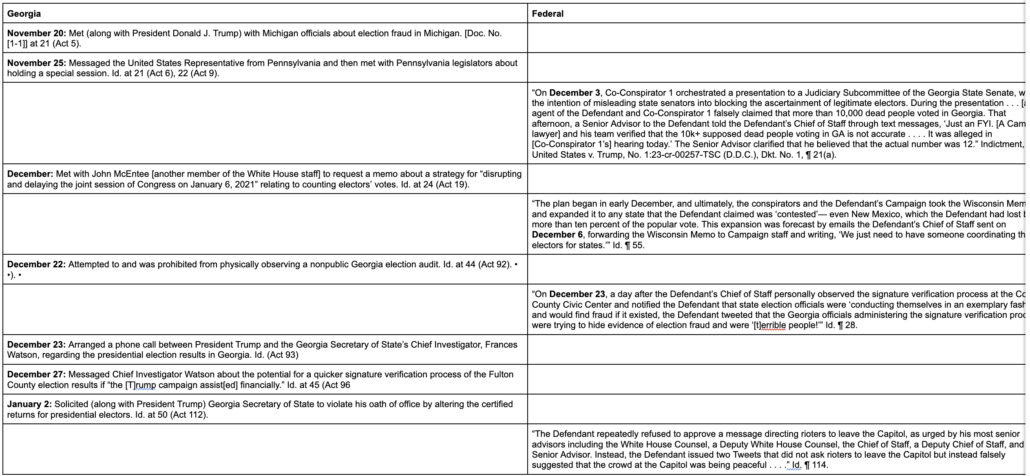

Meadows team recites the alleged Georgia acts as Judge Jones has characterized them on page 19 and then directly quotes the references to Meadows in the federal indictment on page 26. It helps to read them a table together:

There’s an arc here. The early acts in both indictments might be deemed legal information gathering. After that, in early December, Meadows takes two actions, one alleged in Georgia and the other federally, both of which put him clearly in the role of a conspirator, neither of which explicitly involves Trump as charged in the Georgia indictment. Meadows:

- Asks Johnny McEntee for a memo on how to obstruct the vote certification

- Orders the campaign to ensure someone is coordinating the fake electors

The events on December 22 and 23, across the two indictments, are telling. Meadows flies to Georgia and, per the Georgia indictment, attempts to but fails to access restricted areas. Then he flies back to DC and, per the federal indictment, tells Trump everything is being done diligently. Then Meadows arranges and participates in another call. Both in a tweet on December 22 and a call on December 23, Trump pressures Georgia officials again. For DOJ’s purposes, the Tweet is going to be more important, whereas for Georgia’s purposes, the call is more important. But with regards his argument for removal and dismissal, Meadows would argue that he used his close access to advise Trump that Georgia was proceeding diligently.

On December 27, Meadows calls and offers to use campaign funds to ensure the signature validation is done by January 6. This was not Meadows arranging a call so Trump could make the offer himself, it was Meadows doing it himself, likely on behalf of Trump, doing something for the campaign, not the country.

On January 2, Meadows participates in the Raffensperger call, first setting it up then intervening to try to find agreement, but then ultimately pressuring state officials not so much to just give Trump the votes he needs, which was Trump’s ask, but to turn over state data.

Meadows: Mr. President. This is Mark. It sounds like we’ve got two different sides agreeing that we can look at these areas ands I assume that we can do that within the next 24 to 48 hours to go ahead and get that reconciled so that we can look at the two claims and making sure that we get the access to the secretary of state’s data to either validate or invalidate the claims that have been made. Is that correct?

Germany: No, that’s not what I said. I’m happy to have our lawyers sit down with Kurt and the lawyers on that side and explain to my him, here’s, based on what we’ve looked at so far, here’s how we know this is wrong, this is wrong, this is wrong, this is wrong, this is wrong.

Meadows: So what you’re saying, Ryan, let me let me make sure … so what you’re saying is you really don’t want to give access to the data. You just want to make another case on why the lawsuit is wrong?

Meadows was pressuring a Georgia official, sure, but to do something other than what Trump was pressuring Raffensperger to do. His single lie (he was charged for lying on the call separately from the RICO charge), one Willis might prove by pointing to the overt act from the federal indictment on December 3, when Jason Miller told Meadows that the number of dead voters was not 10,000, but twelve, is his promise that Georgia’s investigation has not found all the dead voters.

I can tell you say they were only two dead people who would vote. I can promise you there were more than that. And that may be what your investigation shows, but I can promise you there were more than that.

But even there, two is not twelve. Meadows will be able to challenge the claim that he lied, as opposed to facilitated, as Chief of Staff, Trump’s lies.

Finally, in an overt act not included in the Georgia indictment, Meadows is among the people on January 6 who (the federal indictment alleges) attempted to convince Trump to call off the mob.

There’s a lot that’s missing here — most notably Meadows’ coordination with Congress and any efforts to coordinate with Mike Flynn and Roger Stone’s efforts more closely tied to the insurrection and abandoned efforts to deploy the National Guard to protect Trump’s mob as it walked to congress. Unless those actions get added to charges quickly, Meadows will be able to argue, in Georgia, that his actions complied with federal law without having to address them. If and when they do get charged in DC, I’m sure Meadows’ attorneys hope, his criminal exposure in Georgia will be resolved.

Of what’s included here, those early December actions — the instruction to Johnny McEntee to find some way to obstruct the January 6 vote certification and the order that someone coordinate fake electors — are most damning. That, plus the offer to use campaign funds to accelerate the signature match, all involve doing campaign work in his role as Chief of Staff. For the federal actions, Jack Smith might just slap Meadows with a Hatch Act charge and end the removal question — but that might not help him, Jack Smith, make his case, because several parts of his indictment rely on exchanges Meadows had privately with Trump, and Meadows is a better witness if he hasn’t been charged with a crime.

Aside from those, Meadows might argue — indeed, his lawyers may well have argued to Jack Smith to avoid being named as a co-conspirator — that his efforts consistently entailed collecting data which he used to try to persuade the then-President, using his access as a close advisor, to adopt other methods to pursue his electoral challenges. Meadows’ lawyers may well have argued that several things marked his affirmative effort to leave the federally-charged conspiracies. In this removal proceeding, I expect Meadows will argue that his actions on the Raffensperger call were an attempt, like several others, to collect more data to use his close access as an advisor to better persuade the then-President to drop the means by which he was challenging the vote outcome.

Meadows’ motion to dismiss is weakest because he doesn’t explain there was any federal policy interest in these actions, much less an executive branch one. The early December activities — the order to Johnny McEntee to find a way to delay the vote certification that both the Constitution and the Electoral College Act reserve to Congress and the order to coordinate fake electors overstep executive authority. How Georgia tallies their vote, which Meadows might otherwise claim were efforts to advise Trump, is reserved to Georgia. There’s no federal policy interest here because Trump’s efforts stomped on the prerogatives of both Congress and the state of Georgia.

The 19 pages of Meadows’ motion to dismiss that discuss the law in isolation of the facts mentions the centrality of federal policy 9 times. The part that discusses the facts uses the word “policy” twice (once, which I’ve bolded, in the Secretary of State passage cited above), but makes no effort whatsoever to describe how these actions — particularly the intervention into matters reserved for Congress and the states — pertained to federal policy. These very good lawyers simply never get around to applying their law about intervention, which pivots on federal policy, to the facts. Instead, their argument relies much more heavily on their claim that, particularly since Meadows hasn’t been charged, Willis won’t be able to prove that Meadows’ actions violated federal law. That argument will only matter if they succeed in getting the case removed to federal court.

Between the overt political nature of three of his actions and the lack of any policy argument, Fani Willis should be able to mount an aggressive challenge to this effort, though the effort is not entirely frivolous and Meadows has very good lawyers even if those lawyers don’t have great facts.

But there’s a bunch more going on here.

First, as I noted in this post, these prosecutors are using different strategies to get Trump to trial. Willis, who can’t be fired by Trump if he wins in 2024, charged broadly and presumably hopes to use the RICO exposure to flip some of the key conspirators as witnesses against others. Smith, who may have a much shorter clock (but who also has both indicted crimes, but also his financial investigation, to play off each other), has chosen to charge Trump for January 6 alone, with six people identified as unindicted co-conspirators. Smith seems to believe he can introduce all the evidence he needs to convict Trump relying on the hearsay exception just for those six unindicted co-conspirators. He hasn’t made Meadows a co-conspirator, and so is confident he can get Meadows to take the stand and testify to the facts alleged in the indictment.

Until now, the two investigations have not coordinated, though something Willis said in her press conference suggested that perhaps they’ve started talking now, possibly to exchange evidence as permitted under grand jury rules.

Reporter: Have you had any contact with the special counsel about the overlap between this indictment and–

Willis: I’m not going to discuss our investigation at this time.

Plus, they’ve been working on different tracks. Willis had to take overt steps earlier, mostly last summer, and lost her power to compel testimony in December (though she has immunized all but three of the fake electors in recent months). While DOJ was provably doing covert things during Willis’ overt investigation, most of DOJ’s overt acts took place since Willis lost investigative subpoena power.

Willis, who has close ties to January 6 Committee and certain TV lawyers, may well believe their propaganda about how little DOJ was doing, and likewise may share their (provably incorrect, given what we’ve seen in the Steve Bannon and Peter Navarro contempt prosecutions) view that DOJ could have and should have prosecuted Meadows for contempt for blowing off the J6C. She may believe she needs to, and that it is key to her case, to flip Meadows.

That’s where the ABC report that Meadows changed his testimony about the Iran document is instructive. When he was interviewed in what may have been an interview before the August search of Mar-a-Lago, Meadows said he believed his ghost-writer was incorrect when they claimed Trump had the Iran document in front of him. When Meadows testified before Willis’ grand jury, he offered next to nothing, invoking the Fifth Amendment repeatedly.

Using the Fifth Amendment or citing various legal privileges was a strategy that the grand jury saw from several of the most prominent witnesses, including Trump White House chief of staff Mark Meadows, according to [investigative grand jury foreperson Emily] Kohrs.

“Mark Meadows did not share very much,” she said. “I asked if he had Twitter, and he pled the Fifth.”

Now, at least in the stolen documents probe, Meadows has reversed his prior testimony, explaining that given how damning the facts against Trump are in that case, he thinks his ghost-writer is probably correct about the Iran document being there on the couch.

Meadows also provided compelled, executive privilege-waived testimony since, grand jury testimony obtained before both federal indictments against Trump, grand jury testimony that Smith’s prosecutors used to lock Meadows into a certain story.

These dynamics may explain the curious sequence as portrayed across the two indictments from December 22 and 23, 2020.

On or about the 22nd day of December 2020, MARK RANDALL MEADOWS traveled to the Cobb County Civic Center in Cobb County, Georgia, and attempted to observe the signature match audit being performed there by law enforcement officers from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation and the Office of the Georgia Secretary of State, despite the fact that the audit was not open to the public. While present at the center, MARK RANDALL MEADOWS spoke to Georgia Deputy Secretary of State Jordan Fuchs, Office of the Georgia Secretary of State Chief Investigator Frances Watson, Georgia Bureau of Investigation Special Agent in Charge Bahan Rich, and others, who prevented MARK RANDALL MEADOWS from entering into the space where the audit was being conducted. This was an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy.

On December 23, a day after the Defendant’s Chief of Staff personally observed the signature verification process at the Cobb County Civic Center and notified the Defendant that state election officials were “conducting themselves in an exemplary fashion” and would find fraud if it existed, the Defendant tweeted that the Georgia officials administering the signature verification process were trying to hide evidence of election fraud and were “[t]errible people!”

On or about the 23rd day of December 2020, DONALD JOHN TRUMP placed a telephone call to Office of the Georgia Secretary of State Chief Investigator Frances Watson that had been previously arranged by MARK RANDALL MEADOWS. During the phone call, DONALD JOHN TRUMP falsely stated that he had won the November 3, 2020, presidential election “by hundreds of thousands of votes” and stated to Watson that “when the right answer comes out you’ll be praised.” This was an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy.

Given what Kohrs said about Meadows’ grand jury appearance, we can be sure that all of the claims in Willis’ indictment come from Georgia witnesses. A bunch of people will testify that Meadows tried to force his way into a restricted area — itself suspicious as hell — and Frances Watson will testify that after Meadows reported back, he arranged a call on which Trump harangued her in such a way that is entirely inconsistent with having been told that Meadows told Trump the Georgia investigators were “conducting themselves in an exemplary fashion.”

Meanwhile, that “exemplary fashion” claim could only have come from Meadows’ grand jury testimony, almost certainly in April. Sandwiched between the two overt acts in the Georgia indictment, it is not all that credible. But we can be sure it is locked in as grand jury testimony.

The degree to which subsequent events, including the Georgia indictment, may discredit Meadows’ federal grand jury testimony likely explains why we’ve gotten the first ever leak as to the substance of Meadows’ testimony, which often serves as a way to telegraph testimony to other witnesses. Several of the things ABC describes him as testifying to — that he had no idea Trump took classified documents and that he offered to sort through everything but Trump refused — seem unlikely. But so long as whoever else could refute that (including Walt Nauta, who helped pack up the boxes) tells the same story, he might get away with improbable testimony.

With January 6, though, it’s far less likely he’ll get away with improbable claims before a grand jury, especially if he fails to get the prosecution removed to federal court.

That explains his rush. It explains why Meadows wants to prevent Trump’s and Clark’s motions for removal from causing any delay in his own, which is currently scheduled to be heard on August 28.

Because if and when any other federal crimes come out, his entire argument starts to collapse, particularly given that he failed to argue there was some policy interest in badgering Georgia officials.

Meadows appears, thus far, to have succeeded with a very tricky approach. He has great lawyers and it may well succeed going forward. But with all the indictments flying, that effort gets far more difficult, particularly given the way the overt acts in the Georgia indictment discredit Meadows’ federal grand jury testimony.

Update: I continue to write “Mar-a-Lago” when I mean Bedminster. Fixed an instance of that here.

I don’t think I agree with your reading of the argument made in Meadows’ motion to dismiss. Here’s the core of it:

.

Meadows really is saying that he could have shot and killed those folks he talked to in Georgia (in violation of both state and federal law) and, as long as he was acting in good faith on behalf of then-President Trump, he can’t be prosecuted.

I disagree (though I agree I didn’t focus on the criminal intent part, bc I think it may not get that far, bc of the absence of a policy side).

A more important point is that by pushing the timing of this, Meadows is trying to skip past the removal question to the dismissal question, because until more federal evidence comes out, he’s more likely to succeed on a motion to dismiss than a motion to remove.

As I understand it (and it’s not something I know as well as, say, DC precedents for 1512), it’ll go like this:

1) Was Meadows a federal officer (yes)

2) Were the things he did stuff he did as CoS (maybe)

3) Was he acting on a matter of federal policy (no)

4) Was what he did legal at the federal level (today, arguably yes, possibly not in a month)

5) Is he therefore immune

I may be wrong about when 2 gets applied.

But my point is that this thing will hit some challenges before they get to the legality question, even assuming nothing more gets charged before it is reviewed.

I don’t know enough law to take sides here, but what this post seems to shout between the lines is this case, at large, is gonna take several (maybe 5-6?) years to resolution. So be it, says I. Am I wrong?

I dunno about 5-6 years, but you can just look at other RICO prosecutions DA Willis has done during her tenure and it’s virtually guaranteed this won’t be resolved before the election, regardless of the facts of this specific indictment.

Willis is six months (oops, seven) in to jury selection on her last dumb ass “RICO prosecution”, that of Young Thug. Still can’t get through it. This is the complete bull people are hanging their hats on.

Maybe Trump will get his preferred 2026 trial date, just not in the trial he wants…

Exactly. Willis’ indictment in Georgia (NDGA, 2026 or not) seems to provide incentive for a co-op agreement federally as long as Smith can bring Georgia along in the agreement. Don’t know whether that’s possible but I for one would not like the prospect of an extended state affair that could end up with Valdosta as my living quarters.

Know you’re not a RICO (or a Willis) fan, get it, but would a narrow, non-RICO case be any better? Perhaps I’m blurry with politics and not clearly seeing the best legal approach here

Trump came to power via incessant waves of free coverage of his garbage lies , and endless disparagement, and the country’s bigots lapped it up

I could give a fuck if Willis is a shameless self promoter, that her case is redundant. It doesn’t matter to me so long as that POS,s chances of being reelected continue to plummet. So long as he continues to be skewered daily and negatively , BRAVO. Keep the spotlight on his crimes . Court of public opinion all that matters now and there, he is toast.

I dont care about the intricacies of the law. I only care about Trump not being president, and Fanni Willis case is helping to make him go away.

Yeah. Shit. Why care about the law when you care about only one man. Brilliant.

Agreed. Prosecuting someone just because of what we think about him is about as authoritarian as you can get. Having said that, one thing that distinguishes this case from many others is the amount of evidence that we already have.

DT wanted to try this case in the court of public opinion. He has already succeeded in that. His problem is that he is obviously and without a doubt guilty as hell. So, if Willis is overreaching with her prosecution and making it likely for him to be acquitted, I don’t like that. However, I don’t think for a second that this is a wrongful prosecution based mainly on him just being a gigantic asshole.

Thank you for the compliment although i assure you i am not brilliant. I am satisfied however that this one man , this evil dangerous thing is soon to be placed under arrest, that the entire world will see it and he must under go a trial by his peers, one of which you won’t be. Satisfied and relieved you made no counter argument about his being damaging to his chances for reelection.

He will be pardoned or case dismissed, or he will escape diserved punishment somehow, but for now he must a least face justice. And for that, flaws and all, i thank Ms Willis, the jurrors, the judge, and the witnesses.

The Meadows dismissal motion is a crafty construction which (purposefully) blurs the significant distinction between:

1 the federal policy that the Chief of Staff role should exist

And

2 the proper ambit and limits of that role ie that the conduct in question must be shown to be within ‘the federal official’s executive duties’ as having ‘some nexus in furthering federal policy and in full compliance with federal law’

The motion chosen not to look at what particular federal policy consideration was implicated or being implemented, leading to authorising the actions in question.

The motion instead argues that the actions have some nexus with the •‘role’• of CoS because,

but for being in that role, he would not have been asked to do them;

and that it would have been antithetical to remaining in that role if he had refused to do them.

This is just a dressed up version of “the President willed it so that makes it ok”

I wasn’t around at the time to observe (ahem), nor can find much online, but is Meadow’s “argument” (such as it is) in any way similar to how H.R. Haldeman attempted to defend his actions in court? Seems like an ignominious way to go.

I was in the US visiting relatives at the time of the Senate Hearings.

My knowledge is scant for many reasons.

I briefly perused the DC Appeal Court decision this evening, wondering about the same point you now raise.

I gleaned some sense of his defences to some of the charges, but got no sense from it that his defence was in general terms “I did whatever the boss needed me to do”; though a strong sense that such a statement would accurately encompass both what he in fact did, and how he had justified his actions to himself at the time he did them.

Nice point. A federal court needs to have jurisdiction over the case before it can determine whether to dismiss it. It doesn’t have that until it decides the removal question (or find another basis for jurisdiction).

And how does one “prove” such “faith” to prosecutors and ultimately jurors? It’s a mere claim – I didn’t mean to violate the law when I violated the law, yer Honor …

I’m trying to understand the part about Meadows signalling to others like Nauta as a way to coordinate testimony.

What is the incentive Nauta (or another witness) at this point to help Meadows? Is it that both are essentially tied into the same cover story and if one collapses, they both do?

Or is Meadows essentially threatening that he has the ability to retaliate if someone crosses him? Or is there another issue altogether?

No idea. And it may not be Nauta. Just as likely Susie Wiles.

After all, there is that $1M that Trump’s Save America PAC gave to the Conservative Partnership Institute (CPI) where Mark Meadows wields his political power. Cleta Mitchell is there, too. It’s curious that we haven’t seen her in any of the indictments.

Ms. Mitchell, yes, quite, she was on the same call(s) as Meadows, no? And her firm fired her, and . . . ?

So is she cooperating ?

I don’t see it as Meadows coordinating with specific other defendants through public statements, but as him coordinating with Trump and the other defendants as a whole. For now, they might all imagine themselves as Three Musketeers, a feeling that Republican Party wingnut welfare might reinforce.

That’s likely to break down, though, as less committed or more vulnerable cult members assess – and get closer to – their personal criminal liability. Once they start doing that, Trump’s uniform history in throwing people under the bus may start to affect their reluctance to cooperate. Should any indictments yield convictions and prison terms, that would accelerate the process.

And it’s worth recalling that as of a year ago (at least according to some reporters, including several Team Trump stenographers), Meadows himself was Prime Target for being thrown under the bus to the wolves.

for adam klasfeld: p10 f.3 “margarine”

I’ve been wondering about something procedural.

IF Meadows (or Trump) succeeds in removing his Georgia case to federal court, and IF “any other federal crimes come out” in DC (I assume emptywheel means a superseding indictment or a plea deal involving Meadows), is there a path under federal procedure for the whole thing to be consolidated in Judge Chutkan’s court?

I’ll leave it to the lawyers as a final answer, but it would be doubtful that SC Smith’s DC case could be merged into Willis’ or Cannon’s cases. There is a reason Smith kept everyone else out: to limit the legally permitted delays almost unavoidable with multiple defendants.

SC Smith’s topic is likewise focused as the other case topics are also independently focused, so to joinder these would require a nexus other than Defendant-1 or his minions.

Plus, Willis is in state court, Smith in federal and even if Meadows (et al, I have no doubt Deft-1 and Jeffrey Clark will also try this play) succeeds in moving it to NDGA for a better jury pool, it will still be adjudicated under GA law, prosecuted by Willis. Meadows is also trading an inexperienced RW judge for someone less likely to be sympathetic to him in bench rulings. I wouldn’t be surprised if it does get moved if for no other reason than the Fulton County judge doesn’t want the headaches.

They’ll never be joined.

More charges won’t be a superseding. They’d be a separate indictment.

Removal changes venue from state to federal court, but the underlying case remains an alleged criminal violation of state law. Fani Willis’s team will continue to prosecute them. The principal changes are to the jury pool and the judge. Cases removed to federal court will be heard in the Northern District of Georgia and not consolidated with any that arise in another jurisdiction.

Awesome analysis!

Typo report: Not “It’s where Meadows’ team argues that his actions were legal at the federal level were” — that last word should be “where.”

(Playing henceforth as “The Prog Lib,” previously “The PL”)

[Thanks for updating your username to meet the 8 letter minimum. Do note, though, “The ProgLib” and “The Prog Lib” ar two different names. /~Rayne]

TY

It appears that there is a difference between the ministerial and substantive acts performed by MM. Perhaps he is protected by immunity for performing the ministerial acts as chief of staff, such as making a telephone call at the request of the former president and connecting the president with the phone call recipient. Perhaps MM is not protected by immunity for substantive, overt acts carried out in furtherance of a criminal objective. This looks like an issue a jury must resolve.

I’m reading this as a reason the judge might give for declining the motion to dismiss.

It’s a fact question whether all of the alleged criminal conduct can be classified as part of Meadows’s job as a Cabinet member and executive branch officer. Some of it seems to be campaign and election-related, and not part of his duties. That’s an argument against dismissal at this stage.

Your point begs the question, on which side of the line does participation in a given call lie? If I set up a soap box to the town square, fine; but if I act as a shill in the audience, is that different.

In the end, I’d guess the distinction is moot; I’m sure the role of advocating for the President likewise falls within the scope of official duties.

The counter-argument that holds more sway derives from the Federal ruling in the E. Jean Carroll case where the judge points out repaying the stooge that paid off your paramour falls far afield of official acts. Likewise, the Pres has no role in ascertaining an election’s victor, (the Veep has a minimal and ministerial role), and the CoS can hardly claim his actions merit immunity when his power/role derives from an executive that has no such role, notwithstanding the fig leaf of faithful execution of the laws which was about preventing the Pres from balking and refusing to administer veto overrides.

Do you mean the Stormy Daniels case? Because that is the one where the charges are for the scheme of hiding the charges for paying off the stooge who paid the paramour… I

Whereas IIRC, in the original E. Jean Carroll defamation case, the initial rulings were that defending himself against defamation while president *did* count as part of TFG’s official duties/role (which was being appealed but ended up being dropped later)…

“epic scofflaw”, lol.

I like “Conman Don” or “Don the Con” as an epithet, but epic scofflaw is a great descriptor.

I feel people overlook a fairly damning line from the Raffensperger call, which comes at the end of Meadows’ introductory comments. He says they’re looking for a “less litigious” path forward.

If the courts are the venue for resolution of election disputes, especially involving fraud/malfeasance, then “less litigious” sounds extra-constitutional.

I realize the vast majority of civil suits are settled and that the role of lawyers is more about negotiation than argument before the bench, but when your litigation record (at the time) is ~ 0-56-1, “less litigious” seems to point to motive and smells nefarious.

“less litigious” also sounds a bit like “we really don’t want to hurt you”. Coded phrases.

Just Do The Right Thing And No One Will Get Hurt.

Agree.

scofflaw

[ skawf-law, skof-law]

noun

a person who flouts the law, especially one who fails to pay fines owed.

a person who flouts rules, conventions, or accepted practices.

“epic scofflaw,” Donald Trump.

Minor correction: word missing, probably “state”

The day after the GA indictment, Meadows’ attorneys filed to have it removed from to federal court because he was a senior government official during the events in question;

TY

Lota prufreaders here. One day, they dream, of becoming real grammarians; then they can lecture with some cred about what most of them don’t no. (Fix that senecense kids – is there a comma fault?). I sit uncorrected …

Long career in publishing, here. I automatically note errors, from hash-house menus to major periodicals and books. When people correct me, I appreciate it, as I appreciate people who help Dr. Wheeler repair her rare errors in a prodigious amount valuable text. We all make errors. Clarity is a good thing. Proofreading is not criticism.

Great breakdown but perhaps missing the forrest for the very dense trees and ground cover. Conspiracy is like accessory law. Driving a car perfectly legally to a place when you’ve been hired to do so perfectly legally makes you an accessory before the fact if you know your passenger is going to commit a crime. Driving the passenger away from the location if you even have reason to suspect the passenger has committed a crime makes you an accessory as well. The body of testimony from the January 6 inquiry (ok, you have issues with its work) makes it pretty clear Meadows knew T’s criminal intent, knew T was engaged in extra-legal and/or illegal acts and continued to assist T in various ways enabling that intent and those behaviors. That makes him a co-conspirator, plain and simple.

[Welcome to emptywheel. Please choose and use a unique username with a minimum of 8 letters. We are moving to a new minimum standard to support community security. Because “Me” is absolutely unacceptable as a username nor is “josh” which you used on your first comment, your username will be temporarily changed to match the username/date/time of your first known comment until you have a new compliant username. Thanks. /~Rayne]

Thanks.

Since THIS ANALYSIS explains how conspiracy works, I probably didn’t need your confusion over aid and abet liability with conspiracy.

But since you weighed in, what do you think the criminal intent is, on this RICO charge (as opposed to the obstruction and defraud charges at the federal level)?

But, but, but Popehat said it was RICO!

Certainly just from Meadow’s participation in the call to the GA Sec of State (Count 28), the prosecutors will be able to establish that Meadows knew of should have known what T would attempt in that call and that the attempt when made was unlawful and made by unlawful means. It seems inconceivable and illogical to argue Meadows had no idea what he was enabling as he conducted various subsequent acts including trying to speed up the process of advancing fraudulent electors. His “intent” may have been to “control” various of T’s behaviors and to conduct “damage control” or even just to serve his master as a good servant; but if he knew the illegal conduct was continuing (as he seemingly and most certainly did at minimum during and after that call) that “good intent’ must co-exist with his participation, intentionally, in criminal conduct. “I’m giving him the gun he asked for but I was telling him not to use it in the scheme even though I knew he probably would.” And the notion that his knowledge of even just parts of the overall scheme and his enabling acts in furtherance of those parts was part of his duties as a Federal employee is ludicrous. His duty in that regard was to refuse to participate and if needed, resign. He didn’t.

Mansplain a little proof about Meadows’s knowledge while you’re at it, something that would survive expert cross examination and appeal. Thanks.

Please read my latest reply in this thread. I think any informed woman could write any comment I would make and quite possibly do much better at it. My general point is that in addition to parsing out the particulars it’s important to resume a 5,000 ft view particularly in RICO and/or conspiracy cases. This comment may seem unnecessary to you and others and if so, simply disregard it.

No. It’s important to understand how the law works.

The first question is, was Meadows a federal employee. He was.

As I noted, I THINK the next is, were his actions part of his duty as CoS. Some were. Some arguably were not, but Willis is going to have to convince the judge. That argument will be argued at a particular level.

The point of THIS POST is that attempts to remove the prosecution, particularly those by Meadows and Clark, will involve several steps before you get to the “was it legal” step. And the “was it legal” step will require assessing which parts were illegal federally.

If one just reads Meadows’ brief, it was. However, the sticking point for Meadows in particular was the attempt to crash the counting which really cannot be explained as a WH CoS duty. Willis may not have as hard a time as we think and IIRC she only needs one item to blow Meadows’ claim to bits.

i keep returning to the main post’s text to make sure i haven’t missed something — i’m being just as careful as i can be: who wants to mess up NOW. so i’m slowly scrolling and reading and thinking and checking the DC docket and … there it is. AGAIN. i’m still NOT DONE …

“But there’s a bunch more going on here.”

(and as the day goes by, there will be no doubt more comments, with new ideas and so forth. CONGRATS to us all.)

I think this is a typo:

“She may believe she needs to, and that _is it_ key to her case, to flip Meadows.”

Should be “…it is” ?

Caveat: aging brain so sometimes misread or understand.

Simpleton here.

In the Privilege Log that Rudy submitted to Judge Howell in the Freeman civil suit, there are multiple instances of contacts between Rudy and Meadows that were cited as privileged. If Meadows was truly acting only as a WHCOS (White House Chief Of Staff), then it seems out of line for him to have so much privileged contact with Rudy.

Rudy having privileged communications with Boris Epshteyn maybe can be justified since they are/were of Trump World.

Meadows having communications with White House lawyers such as Pat Cipollone and Patrick Philbin is expected since they were of the White House – Government World.

Rudy and Meadows having a huge amount of privileged communications doesn’t seem to fit with the claim by Meadows that he was only a WHCOS. One of the communications appears to be of a document authored by Katherine Freiss (12/27/2020). There is also a communication that appears to be a document authored by Christina Bobb (12/29/2020). Since both Freiss and Bobb are/were of Trump World, I don’t understand why Meadows as a WHCOS was getting what are very likely campaign related documents.

Since Rudy’s Privilege Log is for Judge Howell’s court, I don’t know if Team Willis can cite it in regards to any filings by Meadows in Georgia.

One of the WHCOS duties is to reduce unnecessary distraction from the President. Coordinating who the President has to directly interact with is part of the daily scheduling of the President’s planned activities by WHCOS. In that role, the WHCOS is generally trusted to make decisions on behalf of communications to and from the President within the parameters the President sets for the WHCOS to follow. Note that a WHCOS might argue that they took some actions that might appear to not be part of WHCOS responsibility to off-load work that might distract the President from >the President’s< official responsibilities…

Meadows might argue that he went down to Georgia in the President's stead…so as to keep the President focused on conducting the President's official duties. Similarly, Meadows might also argue that other things he did, that appear to be part of a conspiracy to game the US electoral system, were done by Meadows to keep the President more focused upon the nation's business. That may or may not be a thin reed, depending on who testifies to what, what evidence there is in either direction, etc.

There were at least 30 instances of communications between Rudy and Meadows.

These appear to have been initiated by Meadows.

1/4/2021 13:50

1/6/2021 13:01

There were also several instances that appear to be campaign related documents sent/forwarded to Meadows.

Auythor: Katherine Friess

~/Library/SMS/Attachments/39/09/at_0_7D12F C2D-5D69-49E3-9CAD- EC7EAC8DB24B/GIULIANI TEAM STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS PLAN – v1.pdf

12/27/2020 21:56

Author: Christina Bobb

~/Library/SMS/Attachments/db/11/at_0_C725 DE5D-6C81-4317-9F19- B4F77182DAB2/AG_USMS_Order.docx 12/29/2020 15:41

I don’t know if Meadows did those things on a Goverment issued phone or his own personal phone. If it was strictly Government business that Meadows was handling for Trump when communicating with Rudy, then it all should belong to the National Archives.

If it was Trump’s personal business such as campaign activity that Meadows was communicating with Rudy about, then Meadows was acting well outside the scope of a WHCOS which is different than what he is claiming in regards to his Georgia legal situation.

I understand about a WHCOS handling some things to make life easier for a POTUS, but I am extremely skeptical about Meadows trying to paint himself as an innocent bystander that acted only as WHCOS for Trump.

In a scenario that has Meadows getting out of his Georgia situation because of his WHCOS claim, then I think that Ruby Freeman’s legal team should ask Judge Howell to force Rudy to give up the communications with Meadows because he was just a WHCOS and that should cancel a presumed Attorney (Rudy) – Client (Trump) privilege claim that Rudy appears to be making.

Rudy has been dragging things out in Discovery in the Freeman civil suit, but I hope Judge Howell puts a stop to it. Maybe she won’t grant a request for everything that Meadows touched, but they should ask anyway.

“But for his position as Chief of Staff which required him to remain close to provide advice, he would not have done the actions alleged.” But if MM actions were for Trump the candidate and not Trump the President, as emphasized in this piece, was he really acting in his capacity of Chief of Staff? I guess I recognize that such a line must be blurry if one is acting as a chief of staff for a president running for re-election. It seems like quite the finesse to me. Or maybe I’m missing a key aspect of it since the gestalt seems to be the argument could work. Is “he told me too, that’s my job, it’s a complicated job, and I was trying to talk him out of it anyway” really the gist of his argument?

This is also where I run aground on the Meadows motion to remove: Trump’s interest as candidate seems personal, versus being part of his institutional interest or role as President. Meadows assisting the candidate seems to be part of the campaign, not part of any federal interest within the scope of Presidential duties, hence not within CoS.

Similar to the nuances involved in parsing Trump’s disparagement of E. Jean Carroll as personal or Presidential, nuances which have now split each way at different times: once being regarded as within his role as President, more recently being reconsidered and deemed to have been personal.

Deep appreciation for the close and comprehensive read by EW & Co. on this site.

Yes. Trump famously draws no distinctions when it comes to meeting his personal wants. He is everything and the only thing, regardless of whether it relates to his conduct as president, as a politician running for office, as a bidnessman, or as a private citizen. Meadows might not see any either. That doesn’t mean federal law draws no distinctions between one sort of conduct and another.

There are at least four categories of conduct that Meadows wants to conflate into one. There’s what he does as a Cabinet member and presidential CoS, what he does for Trump as an individual, what he does to aid his campaign, and what he might do for himself personal reasons. As I see it, only one of those is protected federal conduct.

“Meadows argues that if he weren’t Chief of Staff … he wouldn’t have been doing these unlawful things for Donald Trump, and if he had simply left the room to object, then he wouldn’t be in the room to provide close and confidential advice.”

Does Meadows truly believe that being a high-ranking employee absolves one from culpability for unlawful actions? Many defendants, in many cases, have learned otherwise. As for leaving the room to object, and thereby depriving Trump of his CoS’s ‘close and confidential advice’. Trump’s emphasis on loyalty is well known. If Meadows had overtly indicated any objections, he would have been instantly fired. Meadows’ motivation, plain and simple, was keeping his lucrative job.

As to the motion to dismiss, in addition to the no-federal-policy problem, it seems to me that the no-federal-law-violation prong shouldn’t be read so broadly that the lack of a federal indictment is sufficient to show the acts in question are “consistent with the full range of federal law”. There’s plenty of reasons not to bring charges in a particular case but that doesn’t mean fed laws weren’t pretty obviously broken (eg Hatch Act) or would have been broken (y’know, like insurrection) so as to support a claim for federal officer immunity.

Brilliant and supremely helpful analysis, EW. I had latched on to Meadows’ offer to pay with campaign funds for an expedited audit as evidence of him acting outside any definition of the COS role, which is expansive. You break down the other exceptions in the record, locate them with respect to both Georgia and DOJ prosecutions, and explain the weaknesses within the Meadows team’s motions. Thank you.

I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating: I have NO idea how you do it. I’m just supremely grateful that you do.

Meanwhile, Jack Smith responds in six pages to Trump’s request for a 2026 trial date for his Jan 6th trial. Unsurprisingly, he argues that Trump’s precedents inflate the time required to start a trial, and are not on point.

Trump has had or had access much of the disclosure for some time, it involves substantial duplication, but was carefully organized by the prosecution. Smith points out that defendant’s Luddite lawyers no longer need personally review discovery one paper sheet at a time. Carefully crafted digital searches are now routine, and an industry exists to provide services to lawyers that need to do them. Legitimate scheduling conflicts can be worked out as they arise.

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.258149/gov.uscourts.dcd.258149.32.0.pdf

I liked Smith’s answer to Trump’s complaint that he had asked to schedule jury selection on the very day Trump was supposed to be in Florida for a hearing in another case! Smith said, okay, even though we all know that these dates are not set in stone, I will change my exact date of Dec 11 to sometime during the week of Dec 11.

Jack Smith’s court filings are concise, well-reasoned documents that even contain a kernel of ironic humor. I am in thrall. And this one in six pages leaves Trump’s flimsy rationales about a 2026 trial date in shreds.

(Oh please, let these trials be televised. Shedding light on the Trump trials could save our country from a decade or more of darkness. And he always wanted the highest TV ratings, after all.)

I there a word missing in your block quote of Fanni Willis in her press conference response to a question about her office speaking to or coordinating with federal prosecutors: the word “NOT”?

A wag wrote that the prosecutions of Donald Trump are his campaign strategy.

He has no policies, no plans, no ideas, no nomenklatura he wants to appoint (though FedSoc and others do), no priorities that respect the needs of ordinary Americans. He is running as a victim. The playing field is the courts. It’s about keeping up the level of rage to get out the vote and keep him out of prison.

Even my dog’s tail wag knew this. Was your cited wag actually paid for that? Question is: when do the maga wags actually catch on – and how will they react?

Congratulations to your dog. Have your dog answer the question.

Yep. And Trump not attending primary debates is part and parcel of this strategy. It is a strategy of seeing what he personally can get away with. “They will be mean to me!” is his proclaimed excuse. His ultimate aim is to not have to attend, ultimately ignore, any of the trials he is now facing. I mean, think of how mean those “weak! racist! socialist!” prosecutors and judges are being to poor, poor Donald! The only way he can stay ahead of them all is if you will send him more campaign donations…so his lawyers can continue conducting Donald’s campaign for dominance over all the “weak!” people out to get him.

“ It’s about keeping up the level of rage to get out the vote and keep him out of prison.”

That works both ways, the trick is to rile up the “keep me out of jail” base, without riling up the “lock him up” crowd. Frankly, I don’t think he can pull it off. He campaigned on “lock her up” in 2016 which he doesn’t have this time.

The Lilly Tomlin defence.

I was only running the switchboard.

Please hold.

Our scumbag John Gotti imitating president will be with you shortly.

What does he want ?

Oh, i’m not sure exactly.

Something about you finding votes.

However, when he says ” Give me a break. ” …

You would be smart to do it.

Too bad Raffenberger didn’t record Lilly’s, i mean Meadow’s calls too.

Please hold.

“Cipollone then said something to the effect of, ‘Mark, something needs to be done or people are going to die. And the blood’s going to be on your effing hands. This is getting out of control'”

Cassidy Hutchinson (Former aid to WH Chief of Staff Mark Meadows)

In addition to the above, there are several other things going on with Meadows’ removal motion, I think. As to why Terwilliger is pushing for a fast ruling:

Think about what happens if the federal court grants removal. Not only does that stop the state court proceedings, it opens the door to all 18 other defendants to get into federal court along with Meadows. That’s the usual rule in civil cases (the other defendants come along for the ride), and it’s probably the rule here too. So Trump et al. be in federal court with Meadows. If the judge was not inclined to grant Meadows’ motion to dismiss, that would mean he’d be faced with the possibility of presiding over a 19-defendant complicated state law RICO case under federal rules in federal court. This sort of thing has never happened before, and there’s no/little case law governing the procedures that would be involved. There are civil cases, but criminal defendants have constitutional rights that civil parties don’t. There are some very difficult jurisdictional questions as well. The judge does NOT want to take that on, I promise you!

Meadows is trying to give the judge a clean way out of it: Grant removal, then immediately grant Meadows’ motion to dismiss, and remand the whole thing back to state court. Easy peasy! Well… Probably not in reality. But in any event, to convince the judge to grant removal, Meadows needs to convince the judge the motion to dismiss should be granted as well. Otherwise, the judge would likely be taking on one helluva mess.

There’s another reason why Terwilliger might want to move these proceedings along as fast as possible. He knows more about what went on in the federal GJ proceedings than the DA does. Good attorneys usually have a lot of info about the GJ proceedings if their client is involved at all. GJ secrecy rules don’t extend to the witnesses or their lawyers. A good lawyer will be in communication with the lawyers for the other witnesses. Every time a witness comes out of the GJ, the witness’s lawyer debriefs him/her about what questions were asked, the documents they were shown, etc. The lawyer then passes that along to other lawyers who are friendly with them, and vice versa. Good lawyers will use this knowledge to keep their own clients from getting indicted, and to help prepare them for their own GJ testimony. Meadows was a central witness in the federal GJ proceeding, so Terwilliger surely has a lot of intel on what was said about Meadows.

If there’s more bad evidence on Meadows that came out in those proceedings, Terwilliger probably knows about it, but the DA probably doesn’t. Yet. It’s just a matter of time before Trump’s lawyers show the discovery in the DC federal case to lawyers for other witnesses, and someone down the line will violate the protective order and tell a reporter about it. Once it becomes public, the DA will know about it and try to find a way to get it. Terwilliger would like to get this proceeding on the road before that can happen.

Welcome to emptywheel.

Your first comment was 345 words, your second 524 words, both generally overlong. Yes, other commenters here do write long comments and they are discouraged from doing so unless they are packed with new material or are seasoned commenters who leave longer comments infrequently.

Concision is your friend; optimum comment length is 100-200 words with large blocks of text broken more frequently by paragraph breaks. Users on smaller mobile device screens may scroll by/avoid longer comments altogether rather than read them.

Here are my thoughts on the legal side: Meadows has a decent case for removal, but not enough for the motion to dismiss. The removal standards are broad — the charged acts only have to be “related to” the defendant’s duties under color of office. A court can drive a truck through that “related to” language. Look at the DC Circuit opinion in the Trump International Hotel case. That was a civil lawsuit, but it’s the same statute (28 USC 1442(a)). Now, the Trump Hotel is a private hotel; Trump was running even before he was president. How can running a private hotel be “related to” the president’s official duties? Well the DC Circuit said it was.

For removal, Meadows also has to set forth a “plausible” or “colorable” federal defense — in this case, immunity. (He adds a couple federal defenses in the mtn to dismiss, but they’re throwaways).

To win the motion to dismiss, Meadows has to actually show he has immunity (a high standard than the pleading standard). It’ll be judged on a summary judgment kind of standard: If the DA can demonstrate there’s a dispute over any material issue of fact, Meadows loses.

This is where you get to the Hatch Act. You can’t get immunity if your actions violated federal law. I’m not a Hatch Act expert, but it seems like a lot of Meadows’ conduct was campaign-related and likely violated the Hatch Act. (That’s in addition to the argument that Meadows violated federal criminal laws of the kind alleged in the DC federal indictment against Trump.) If the DA can show there are disputed facts on these issues, Meadows loses.

So I think it’s going to be very hard for the district court to grant a motion to dismiss, even if it wanted to. That means it’s also very unlikely the court will grant removal, because once it does, that’s letting camel’s nose under the tent, and the court is looking at the possibility of taking on the whole mess if it doesn’t also grant the motion to dismiss.

I have been pondering Meadows defence strategy a lot, in the light of what may be gleaned from the filings.

Re removal – it is a low bar to cross. The needs to be a showing by him that there is a plausible federal defence.

In this instance that he was at all times acting within his role as CoS.

The motion to dismiss is used by him to robustly set out the most capacious version of this, in effect stating that the contrary view is unarguable, but it also argues in the alternative that the evidentiary hearing on removal is into the plausibility of the defence should conclude that it is at least plausible such that it should be a federal court which should try the issue at trial.

There is a possible subtlety to that way that the dismissal filing characterises the role of CoS- a subtlety which evaded me at first reading – but which arises from this passage:

“ Only by virtue of his Chief of Staff role was Mr. Meadows involved in the conduct charged. Put another way, his federal position was a but-for cause of his alleged involvement. Moreover, if Mr. Meadows had absented himself from Oval Office meetings or refused to arrange meetings or calls between the President and governmental leaders, that would have affected his ability to provide the close and confidential advice that a Chief of Staff is supposed to provide.”

What advice is the CoS supposed to provide when the President is being lured by other reckless advisers to adopt unwise paths which raise a potential of a conflict between the Presidency and the authority of States to conduct and to oversee elections?

The role of the CoS should be to use his best endeavours to advise and persuade his principal not to behave unwisely,surely? And persuading this famously stubborn President requires subtlety patience tact and skill.

Meadows has on his side a number of wrinkles in the evidence and can point to the fact that his actions on these issues as evidenced by material hands of the SC prosecutors, which evidence is being treated by them as founding part of their narrative about the CoS within their indictment of Trump. On that evidence his actions are not treat as those of a co-conspirator, but someone who has sought to persuade the President that there was no there there as far as Georgia is concerned. Indeed his actions during the phone call again should be interpreted in the same light.

His role, as he saw it was to placate the President enough so that the President would not doubt his loyalty, and give him the opportunity to seek to further persuade him to adopt a wiser course that that being advocated by others. He needed to “stay in the room”

So his defence is Trump may be guilty but amused my best endeavours to dissuade him – those endeavours may have been shown to be insufficient, but they show I was not a Co-conspirator..

I don’t know if this is a reasonable characterisation of how Meadows will play his hand, but it is perhaps going to be something along those lines albeit presented with greater finesse by his famously excellent lawyer..

Apologies for numerous typos.

Please read past them if you are interested in reading at all.

“In this instance that he was at all times acting within his role as CoS.”

Careful — there’s two different things the court has to rule on. First, the court decides whether to grant removal. If it denies removal and remands to state court, it doesn’t rule on the motion to dismiss. But if it grants removal, then it has to rule on the motion to dismiss.

The standard for ruling on removal is different (and broader) than the standard for the motion to dismiss, but there is some overlap in the issues involved. (Both involve immunity, and whether Meadows can make a case for immunity.)

Consider the removal standard first. It’s in 28 USC 1442 (a). Setting aside the immunity issue for a second, Meadows has to show something else: He has to show the acts charged in the the state include any act done under “color of office”, OR any act “related to” acts performed under color of office. That “related to” phrase makes the standard really broad and easier for Meadows to meet. Some courts have interpreted it to include an element causation (hence the “but-for” language). The Eleventh Circuit in another case has said “related to” means “connected to” or “in association with”, which doesn’t do much to clear things up. The bottom line is that if you’re even moderately creative, you can come up with a connection.

To get removal, Meadows also has to show he has a “plausible” or “colorable” federal defense. He’s assert three federal defenses here, but the main defense is immunity. So to get removal, he has to make a plausible case for immunity.

If the district court grants removal, then it has to decide the motion to dismiss. Then the standard for judging immunity gets raised — it isn’t just “plausible” immunity, it’s whether he really has immunity. The immunity question starts to get tricky, and the law on exactly what has to be shown is somewhat debatable. But if he intentionally violated some criminal law, he can’t get it. So if the DA can show that there’s some material factual dispute that puts it in doubt (e.g., Meadows knowingly and intentionally violated the Hatch Act), Meadows loses the motion to dismiss for immunity.

Edit to the above: The phrase “if he intentionally violated some criminal law” should be “if he intentionally violated some FEDERAL law”.

I’ll add one thing about the difference between the “immunity” and “color of office” requirements for removal. This is confusing, and a lot of people mix them up.

The “color of office” or “related to color of office” is written in the language of the removal statute 28 USC 1442(a). There’s nothing in the language of the statute mentioning any requirement to show any federal defenses, immunity or otherwise.

SCOTUS in Mesa v. California interpreted the removal statute as including the requirement that the defendant show a plausible federal defense. (It’s necessary to prove a jurisdictional hook for the federal court under Art. III.)

The Mesa opinion basically tacks the “plausible federal defense” requirement onto the “color of office” language, and it’s natural to get these two requirements mixed up, but for purposes of the analysis, it’s better to think of them as two separate requirements. There’s some overlap in the issues involved, especially if the defense is immunity, but suffice it to say you can meet the “color of office” requirement without meeting the “plausible federal defense” requirement.

(Hmm.. looks like the other comment I made was not approved by the moderator. But there was more. Apologies for the word count, but really, these are complicated issues. I think I’m actually pretty concise, and I would suggest they’re pretty informative, perhaps you’ll reconsider.)

I am more than ready to accept that I have found grappling with the subtleties of related. perhaps overlapping but nevertheless distinct concepts, which have to be applied in distinct stages of a decision making process, to be a difficult exercise, combing procedural and substantive nuance.

It is not helped by the fact that in U.K. law ‘colour of office’ most usually is pleaded in respect of ‘purporting to act under colour of office’.

Nevertheless – I am happy to try to reframe the argument :

Meadows will argue something along these lines:

1 for the purpose of removal that he was acting under the colour of office

2 And for the purpose of dismissal that he has immunity

In each instance because the exercise of his office in advising the President involves him in deciding how best to arm himself with information and how best to deploy that information to persuade the President not to adopt an unwise path. And all his actions are what he judged, in his discretion, to be necessary at the time to achieve that goal.

BTW, another wild card: Assuming the district court denies removal and remands the case, it’s almost certain Meadows will appeal the Eleventh Circuit. Both removal and remand are appealable. Because there’s so much leeway in the broad removal standards, and because this involves the scope of a chief of staff’s official duties, there’s a very good chance an Eleventh Circuit panel would reverse. There’s a decent chance it could go to SCOTUS too. These are very novel questions in a very novel context, and they are incredibly important issues on several level. The DA had better make a damn good record in the district court. Terwilliger certainly will.

Terwilliger has the DA out of her home field advantage in this thing. She had better get some fed crts experts on her team if she doesn’t already have them. The deeper this case gets into federal court, the harder things get for the DA. There are some very tricky procedural and jurisdictional issues to navigate, and the longer this goes on, the more like the higher courts get involved and reverse.

The removal procedure gets used a lot in civil cases, but it’s comparatively rare in criminal cases. Most of the modern cases involve a federal agent who gets charged in state court after he/she kills someone, gets caught up playing both sides in a drug/corruption investigation, that sort of thing. The federal court grants removal and grants the motion to dismiss, done and done. Try finding a case involving multiple defendants, some of whom have no federal defense (like the electors — no way they come under the removal statute). It doesn’t exist. There’s basically no case law governing the sorts of procedures involved with that, much less a 19-defendant state law RICO case. These are deep, choppy, uncharted waters. And Terwilliger would love to drag the DA out into them. So would a lot of the other defendants, I bet. But Terwilliger is best suited to navigate them.

Also, on the appeal: Take note of 28 USC 1455(b)(3), which lets state court proceedings continue unless/until removal is granted. There’s one thing the state court can’t do though: “a judgment of conviction shall not be entered unless the prosecution is first remanded.” Now, does that mean the state court couldn’t enter a guilty verdict if the removal matter is still on appeal in the Eleventh Circuit by the time the trial nears completion? (Because it most likely will be for a while). I’m not sure. Technically, the district court will order remand if it denies removal, and while Meadows can appeal, the usual rule is that an appeal doesn’t stop the order from taking effect unless a stay is granted. But I can imagine that happening at some point, especially if the higher court think there’s merit here. Now, that’s all looking way far ahead, but if I’m Meadows, I’ve gotta like the possibility of a backstop against going to prison, even if removal gets denied. Probably another reason why he would want to file for removal.

507 words. Please, I beg you, work on concision or risk being stuck in moderation.

Signed,

Your friendly site moderator

My apologies — I put in those comments before I saw your reply re the word limit.

FWIW, I have a lot of relevant experience (former white collar defense atty among other things) so I hope my comments will have some value for you.

And there are some really complicated issues at play here. You could write several law review articles based on some of the issues I mentioned above. I do try to be concise, but it’s complex stuff.

I would also challenge this a bit:

“Since the Supreme Court’s seminal decision in Neagle, federal courts have consistently held that federal agents are immune from state-law prosecution so long as they did not violate federal law maliciously or with criminal intent.”

Meadows too makes the argument in his mtn to dismiss that courts have to evaluate whether the defendant was acting with an honest, good faith belief under federal law. I think it’s more nuanced than that. Look at the cases cited. They are easily distinguishable on their facts. For example, Meadows relies heavily on Baucom.

In Baucom, the Eleventh Circuit case, an undercover FBI agent (Baucom) ran a sting operation that involved offering a bribe to a state prosecutor in order to snare that prosecutor on corruption charges. The state turned around and threatened to charge the FBI agent under state law corruption charges. The agent moved for removal, and the federal court granted it.

In the course of holding the agent had immunity, the Eleventh Circuit noted, “There is no suggestion that Baucom acted because of any personal interest, malice, actual criminal intent, or for any other reason than to do his duty as he saw it. His good faith cannot be seriously questioned.”

Here, Meadows’ good faith can seriously be questioned, and I have no doubt the DA will do so. I would also guess there is a lot of evidence in other places to show that Meadows was well aware things like this were prohibited under the Hatch Act. These guys certainly ignored the Hatch Act, but someone like Meadows would have understood very well what it prohibited.

Also, how does Meadows prove up good faith here? He can’t take the stand and testify. What’s he going to put on the record to show he didn’t think he was violating the Hatch Act when he offered to give election officials money from the campaign if they needed it for a recount?

One of the reasons I was given for having my civil case moved from state to federal court was because the local library system’s budget received a portion of their funds from the federal government (funneled through the state.) I have no idea whether or not this is a valid argument. The other reason was because I was claiming my First Amendment rights had been violated, which seemed like a substantial claim to me, but I simply accepted the advice of counsel about the removal.

If the federal funding is actually a legitimate reason, though, couldn’t that be used to move the GA case? That’s assuming Atlanta received any federal election funding.

“The Path of Federal Election Funding” – Jun 16, 2022

“From state to local”

“Total time: varies by state

It takes years for states to plan for and spend funds. Unlike the process for grant money going from federal to state government, the process from state to local government is variable from state to state. States may transfer funds directly to local units of government or they can use funds for in-kind support of local election offices.”

https://bipartisanpolicy.org/explainer/federal-election-funding-path/

Question: there’s an obvious tension between the legal delineation of Meadows’ duties and the practical expectation of his loyalty and availability to the President. I can imagine this tension was never higher than during the Trump administration, but it seems it must exist to some extent always — it’s sort of built in to the job.

Given this, is there an established way for CoS’s to handle this? “I’m sorry, Mr. President, but I’m not permitted to help you with this issue.”? As a practical matter, Meadows seems to have been drawn into this by Trump (something any other president would have known not to do in the first place). And it’s hard to imagine that a refusal to give advice would have gone over very well. (Notwithstanding, it’s also hard to muster much sympathy. The man made his bed, many times over.) Appreciate any light anyone can shed on this.

Mark Meadows,Trump’s Chief of Staff, knows the difference between official and political acts. Contacting a bunch of Georgia officials in high offices just to say hi? Doubt it. Pushing Trumpworld voter fraud claims and crashing into GA election officials’ vote audits are not official acts, either.

I see a lazy, hapless man, sitting on his couch, looking at his phone as Cassidy Hutchinson implores him to do something about the violence raging at the Capitol.

> Meadows is a better witness if he hasn’t been charged with a crime.

Why? Because his testimony won’t appear coerced or influenced?