On January 19, 2022, SCOTUS Upheld Judge Tanya Chutkan’s Decision Rejecting Trump’s Executive Privilege Claims

On November 9, 2021, Judge Tanya Chutkan — the judge who randomly got assigned to Trump’s January 6 prosecution — rejected Trump’s request to enjoin the Archives from turning over documents to the January 6 Committee.

Chutkan held that because the incumbent President had waived Executive Privilege and the January 6 Committee had a legislative interest in preventing another attack on the peaceful transfer of power, she had no reason to second guess the political branches of government about the import of the investigation.

The legislative and executive branches believe the balance of equities and public interest are well served by the Select Committee’s inquiry. The court will not second guess the two branches of government that have historically negotiated their own solutions to congressional requests for presidential documents. See Mazars, 140 S. Ct. 2029-31.

Defendants contend that discovering and coming to terms with the causes underlying the January 6 attack is a matter of unsurpassed public importance because such information relates to our core democratic institutions and the public’s confidence in them. NARA Br. at 41. The court agrees. As the Supreme Court has explained, “the American people’s ability to reconstruct and come to terms” with their history must not be “truncated by an analysis of Presidential privilege that focuses only on the needs of the present.” Nixon v. GSA, 433 U.S. at 452-53. The desire to restore public confidence in our political process, through information, education, and remedial legislation, is of substantial public interest. See id.

Plaintiff argues that the public interest favors enjoining production of the records because the executive branch’s interests are best served by confidentiality and Defendants are not harmed by delaying or enjoining the production. Neither argument holds water. First, the incumbent President has already spoken to the compelling public interest in ensuring that the Select Committee has access to the information necessary to complete its investigation. And second, the court will not give such short shrift to the consequences of “halt[ing] the functions of a coordinate branch.” Eastland, 421 U.S. at 511 n.17. Binding precedent counsels that judicially imposed delays on the conduct of legislative business are often contrary to the public interest. See id.; see also Exxon Corp. v. F.T.C., 589 F.2d 582, 589 (D.C. Cir. 1978) (describing Eastland as emphasizing “the necessity for courts to refrain from interfering with or delaying the investigatory functions of Congress”).

Accordingly, the court holds that the public interest lies in permitting—not enjoining— the combined will of the legislative and executive branches to study the events that led to and occurred on January 6, and to consider legislation to prevent such events from ever occurring again.

On December 9, 2021, the DC Circuit upheld Chutkan’s ruling. Patricia Millett repeated Chutkan’s argument that the agreement of Congress and the Executive provided no basis for the courts to intervene. But she also described that even by a heightened standard — even if Trump were withholding these documents while still President — the need for the documents would overcome his privilege claim.

While former President Trump can press an executive privilege claim, the privilege is a qualified one, as he agrees. See Nixon v. GSA, 433 U.S. at 446; United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. at 707; Appellant Opening Br. 35. Even a claim of executive privilege by a sitting President can be overcome by a sufficient showing of need. See United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. at 713; In re Sealed Case, 121 F.3d at 292. The right of a former President certainly enjoys no greater weight than that of the incumbent.

In cases concerning a claim of executive privilege, the bottom-line question has been whether a sufficient showing of need for disclosure has been made so that the claim of presidential privilege “must yield[.]” Nixon v. GSA, 433 U.S. at 454; see United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. at 706, 713. 12

In this case, President Biden, as the head of the Executive Branch, has specifically found that Congress has demonstrated a compelling need for these very documents and that disclosure is in the best interests of the Nation. Congress, which has engaged in a course of negotiation and accommodation with the President over these documents, agrees. So the tests that courts have historically used to police document disputes between the Political Branches seem a poor fit when the Executive and Congress together have already determined that the “demonstrated and specific” need for disclosure that former President Trump would require, Appellant Opening Br. 35, has been met. A court would be hard-pressed under these circumstances to tell the President that he has miscalculated the interests of the United States, and to start an interbranch conflict that the President and Congress have averted.

But we need not conclusively resolve whether and to what extent a court could second guess the sitting President’s judgment that it is not in the interests of the United States to invoke privilege. Under any of the tests advocated by former President Trump, the profound interests in disclosure advanced by President Biden and the January 6th Committee far exceed his generalized concerns for Executive Branch confidentiality.

[snip]

Keep in mind that the “presumptive privilege” for presidential communications “must be considered in light of our historic commitment to the rule of law.” United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. at 708. In United States v. Nixon, the particular component of the rule of law that overcame a sitting President’s assertion of executive privilege was the “right to every [person]’s evidence” in a criminal proceeding. Id. at 709 (quoting Branzburg v. Hayes, 408 U.S. 665, 688 (1972)). Allowing executive privilege to prevail over that principle would have “gravely impair[ed] the basic function of the courts.” Id. at 712.

An equally essential aspect of the rule of law is the peaceful transition of power, and the constitutional role prescribed for Congress by the Twelfth Amendment in verifying the electoral college vote. To allow the privilege of a no-longer-sitting President to prevail over Congress’s need to investigate a violent attack on its home and its constitutional operations would “gravely impair the basic function of the” legislature. United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. at 712.

On January 19, 2022, the Supreme Court upheld Chutkan’s ruling. With only Clarence Thomas dissenting, Justice Kavanaugh noted that the DC Circuit’s ruling that Trump’s appeal would have failed even under more stringent standards made any review of this decision unnecessary.

The Court of Appeals concluded that the privilege claim at issue here would not succeed even under the Nixon and Senate Select Committee tests. Therefore, as this Court’s order today makes clear, the Court of Appeals’ broader statements questioning whether a former President may successfully invoke the Presidential communications privilege if the current President does not support the claim were dicta and should not be considered binding precedent going forward.

I have written repeatedly about how Merrick Garland set up a framework in July 2021 by which Congress’ investigative requests would provide an opportunity for President Biden to waive Executive Privilege without violating DOJ’s contacts policy. That is, in July 2021, Garland solved a tricky problem with investigating the former President: how to obtain privilege waivers while keeping the existing President entirely walled off from the criminal investigation.

But this legal background, in which, with just one dissent, SCOTUS upheld a Tanya Chutkan opinion pertaining to an investigation into Donald Trump, will prove critically important in the days ahead, for two reasons that go to the screeds the former President is engaging in on his failed social media platform.

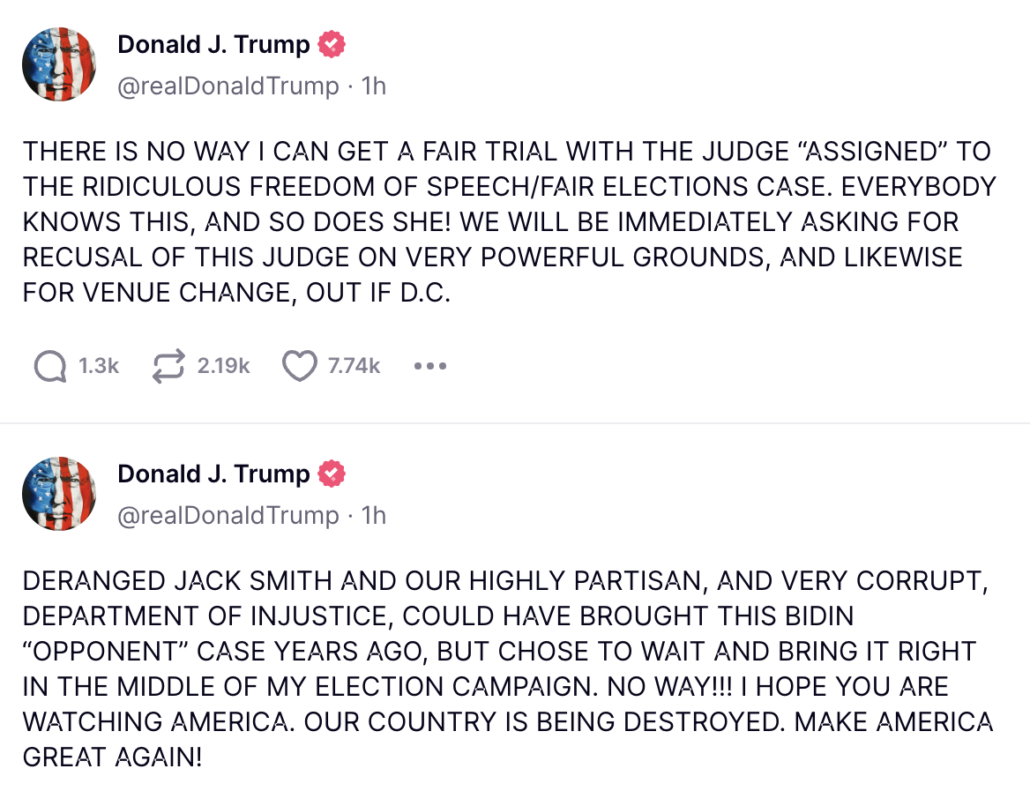

Along with making a venue complaint that has failed the dozens of times other January 6 defendants have made it (here’s a Roger Parloff post from before the Riley Williams and Oath Keepers trials showed that juries will rule against the government on precisely the same charges), Trump is preparing to claim that Judge Chutkan is biased and must be recused.

And Trump has been claiming that DOJ could have brought this case years ago, before the election season.

As to the first point, on a topic directly pertinent to this investigation, eight Justices have already upheld Judge Chutkan. Three Trump appointees, with Justice Kavanaugh writing the decision, have already ruled with Judge Chutkan.

That will make it harder to claim her prior central involvement in the January 6 investigation presents a conflict.

More importantly, that Judge Chutkan decision in November 2021 led to a SCOTUS decision, on January 19, 2022, upholding the DC Circuit’s opinion that the peaceful transfer of power is a sufficiently important basis to overcome an Executive Privilege claim, even if only for a congressional investigation, which litigation in the stolen documents case noted was a significantly lower standard than a criminal investigation.

Yet, even in spite of that decision on January 19, 2022, Donald Trump continued to make Executive Privilege claims that delayed DOJ’s investigation. He did so to stall DOJ’s interviews with Mike Pence’s advisors in summer 2022. He did so to stall DOJ’s interviews of Trump’s White House Counsel later that summer. He did so to stall DOJ’s interviews with other top aides in January 2023. And he did so to stall Mike Pence’s testimony.

Donald Trump continued to stall DOJ’s investigation using Executive Privilege claims for 463 days after a Justice that he himself had appointed had already rejected such claims. At the very least, these frivolous Executive Privilege invocations were critically responsible for any delay from July 2022, when Greg Jacob and Marc Short first refused to answer some questions because of Trump’s privilege claims, until April 2023, when Mike Pence testified — nine months.

Nine months, Trump kept making Executive Privilege claims that it was clear SCOTUS wouldn’t uphold.

Indeed, Trump’s frivolous Executive Privilege claims are responsible for even more of any delay than his own Special Master demand in the stolen documents investigation caused — in that case, three months.

Donald Trump is complaining that he wasn’t charged for his attempt to overthrow the peaceful transfer of power in 2020 until during his campaign to regain the presidency.

But he is personally responsible for much of that delay.