Judge Jesse Furman Gives DOJ 3 Pages to Reply to emptywheel’s Bid to Liberate Sealed Transcripts on the Espionage Act

Some weeks ago, I described that, with the help of National Security Counselors, I was intervening in the Joshua Schulte case to try to liberate transcripts from a May 3 sealed Classified Information Procedures Act hearing in which this exchange took place.

I gave you two hypotheticals. I think one is where a member of the public goes on WikiLeaks today and downloads Vault 7 and Vault 8 and then provides the hard dive with the download to someone who is not authorized to receive NDI, and I posed the question of whether that person would be guilty of violating the Espionage Act and I think your answer was yes. That strikes me as a very bold, kind of striking proposition because in that instance, if the person is not in a position to know whether it is actual classified information, actual government information, accurate information, etc., simply providing something that’s already public to another person doesn’t strike me as — I mean, strikes me as, number one, would be sort of surprising if that qualified as a criminal act. But, to the extent that the statute could be construed to the extend to that act one would think that there might be serious constitutional problems with it.

I also posed the hypothetical of the New York Times is publishing something that appears in the leak and somebody sharing that article in the New York Times with someone else. That would be a crime and there, too, I think you said it might well be violation of the law. I think to the extent that that would extend to the New York Times reporter for reporting on what is in the leak, or to the extent that it would extend to someone who is not in position to know or position to confirm, that raises serious constitutional doubts in my mind. That, to me, is distinguishable from somebody who is in a position to know. I think there is a distinction if that person transmits a New York Times article containing classified information and in that transmission does something that confirms that that information is accurate — right — or reliable or government information, then that’s confirmation, it strikes me, as NDI. But it just strikes me as a very bold and kind of striking proposition to say that somebody, who is not in position to know or does not act in a way that would confirm the authenticity or reliability of that information by sharing a New York Times article, could be violating the Espionage Act. That strikes me as a kind of striking proposition.

CIPA is the means by which the government tries criminal cases involving classified information. It permits the government to ask to hold certain hearings about what evidence will be admitted in sealed hearings to avoid any possibility that classified information will be publicly disclosed at those hearings.

[Note, these transcripts were funded by Calyx Institute with funding provided by Wau Holland Foundation, the latter of which has close ties to WikiLeaks.]

While everyone else was staying up late waiting for the January 6 Committee Report last Thursday, I was staying up late to see the filing that Kel McClanahan submitted in that intervention, which is here.

In the filing, McClanahan argued that the government’s own argument in support of sealing the transcripts attempted to use wiretap precedents to justify their continued sealing of CIPA hearings, even though they were asking to seal something else — hearings at which classified information might or might not be discussed.

It goes without saying that the proceedings in question—and the transcripts thereof—are judicial records for purposes of the common law, and the Government does not make any serious argument to the contrary. Instead, it argues that CIPA established a presumption against disclosure, drawing an analogy to the statutory provision for sealing of wiretap applications at issue in In re New York Times Co. to Unseal Wiretap & Search Warrant Materials, 577 F.3d 401 (2d Cir. 2009). It then goes beyond that analogy to argue that the presumption is even stronger because Congress allowed for wiretap materials to be unsealed for good cause but provided no comparable mechanism for CIPA proceedings. However, CIPA is not Title III, and the Government’s argument requires that to be the case in order to succeed.

Simply put, In re New York Times dealt with a statute which included a “manifest congressional intent that wiretap applications be treated confidentially,” id. at 408, but only because it includes a provision that the records themselves “shall be disclosed only upon a showing of good cause before a judge of competent jurisdiction.” 18 U.S.C. § 2518(8)(b). In contrast, CIPA only provides that a hearing shall be held in camera because “a public proceeding may result in the disclosure of classified information.” 18 U.S.C. App 3 § 6(a) (emphasis added). It in no way exhibits any intent that the records created from such a hearing should be presumed undisclosable, nor could it, since by its own terms the hearing might actually include no classified information. In other words, CIPA merely provides a protective procedure to guard against the chance that a hearing may include classified information,2 based solely on the Attorney General’s assertion that it may include classified information—hardly a high bar for the Government to clear. Congress voiced no opinion about what should then happen to the unclassified information included in that hearing, let alone a “manifest congressional intent.”

McClanahan laid out how the CIPA discussions at issue played a role in the exercise of Article III power, noting that the transcripts in question address the elements of the charges against Schulte: the very definition of the Espionage Act (and its application to someone like me, who might be held accountable for disseminating unconfirmed classified information).

The key question then becomes, what was the “role of the material at issue in the exercise of Article III judicial power” and its “resultant value . . . to those monitoring the courts?” United States v. Amodeo, 71 F.3d 1044, 1049 (2d Cir. 1995). The Court itself addressed both of these issues at various times. Most relevantly, it engaged in open court in an extensive discussion of a colloquy that appears to have taken place in the 3 May hearing, telling Government counsel, “I gave you two hypotheticals” about the Government’s interpretation of the scope of the Espionage Act. (Tr. of 7/6/22 Hrg. at 149:3-151:12.) It did so in the context of a discussion of potential jury instructions, and expressed the sentiment several times that the Government’s assertion that a person sharing National Defense Information (“NDI”) that is already in the public domain would still be liable under that statute was “kind of a striking proposition.” The role, then, of these transcripts—and the information they contain—in the exercise of Article III judicial power is clear, as is the resultant value to people monitoring the judicial process. In this case, according to this Court, the Government has—behind closed doors—pressed an argument that a person can violate the Espionage Act by handing a copy of a New York Times article containing leaked NDI to someone else, which is definitely something that interested persons in the field should know, and what they do not know is the degree to which the Government pressed this point, how it defended it, whether it has actually done so in the past, and what other positions it took when it was not expecting the transcripts to become made public.

By the same token, this convergence of factors also definitively demonstrates that the First Amendment right of access attaches to these records, because unlike the hypothetical CIPA hearing that the Government asks the Court to envision, at least this discussion strayed far from a simple discussion of evidentiary issues, with the Government presenting legal arguments about elements of the crime itself. [McClanahan’s italics, my bold]

He argued that the government’s argument went further than the stance it takes on Prepublication Reviews, insofar as we’re just arguing for a First Amendment right to read these transcripts, not publish them.

Simply put, when courts are put in the position of balancing claims related to national security against a writer’s First Amendment concerns, they consistently and without exception find that only classified information tilts the balance. There is no reason for this dynamic to change when it involves a reader’s First Amendment concerns, and while we acknowledge that some district courts have accepted the Government’s arguments, there is no evidence to show that those courts were presented with our argument and no grounds for this Court to follow suit.

Then McClanahan pointed to Judge Furman’s own comments about the colloquy as proof that the government’s claim — that there is no meaningful way to unseal just the unclassified portions of the transcripts — must be false.

In fact, the very existence of the Court’s 6 July summary of the two hypotheticals discussed above demonstrates the frivolousness of these arguments, since: (a) it was neither incoherent not functionally useless; and (b) the Court presumably did not divulge classified information in discussing it.

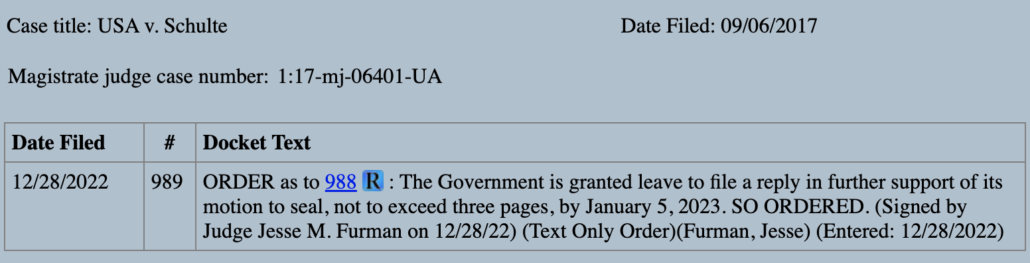

Judge Furman must have found something novel or persuasive in this argument. When he ordered the government to formally request the continued sealing of the transcripts on November 21, he said they could only submit a reply with his permission. But he just gave the government three pages to to do so.

This challenge could do more than liberate arguments the government made about the Espionage Act in secret. It could challenge the government’s larger views on secrecy in the context of CIPA.

As McClanahan laid out, “the Government has—behind closed doors—pressed an argument that a person can violate the Espionage Act by handing a copy of a New York Times article containing leaked [classified information] to someone else.” When I saw the argument (as relayed in Furman’s July description), I recognized the import of liberating this transcript.

I was only able to make this challenge because McClanahan was able and willing to help — and he can only do so through the support of his non-profit. If you believe fights like this are important and have the ability to include it in your year-end donations, please consider supporting the effort with a donation via this link or PayPal. Thanks!