I’ll have a lot to say about Judge Aileen Cannon’s outrageous order enjoining the government from conducting a criminal investigation into violations of the Espionage Act. I want to start with the way that she has chosen to risk Donald Trump’s attorney-client privilege in order to vindicate it.

Cannon didn’t just order a Special Master be imposed to review a subset of 520-pages of material set aside as potentially privileged (something that would be unexceptional, but something that would actually give Trump’s lawyers less involvement than the filter team was preparing to give his lawyers last week, when they wanted to hand these documents over directly to Trump’s lawyers).

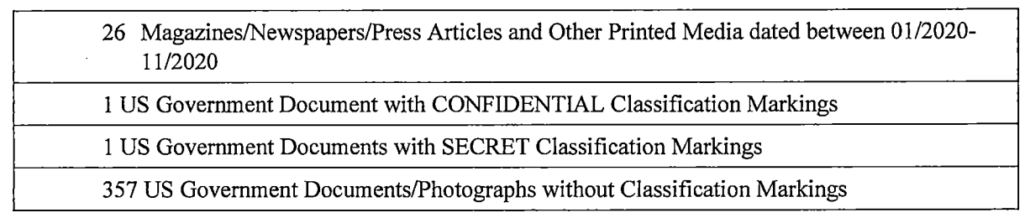

Those amount to 64 sets of documents out of the 11282 seized on August 8 — less than 4.6% of the seized documents (and likely close to .5%).

She said that because the filter team worked better than mandated by the warrant, it was proof the filter team wasn’t working, and so a Special Master would have to go over everything again.

To begin, the Government’s argument assumes that the Privilege Review Team’s initial screening for potentially privileged material was sufficient, yet there is evidence from which to call that premise into question here. See In re Sealed Search Warrant & Application for a Warrant by Tel. or Other Reliable Elec. Means, 11 F.4th at 1249–51; see also Abbell, 914 F. Supp. at 520 (appointing a special master even after the government’s taint attorney already had reviewed the seized material). As reflected in the Privilege Review Team’s Report, the Investigative Team already has been exposed to potentially privileged material. Without delving into specifics, the Privilege Review Team’s Report references at least two instances in which members of the Investigative Team were exposed to material that was then delivered to the Privilege Review Team and, following another review, designated as potentially privileged material [ECF No. 40 p. 6]. Those instances alone, even if entirely inadvertent, yield questions about the adequacy of the filter review process.13

13 In explaining these incidents at the hearing, counsel from the Privilege Review Team characterized them as examples of the filter process working. The Court is not so sure. These instances certainly are demonstrative of integrity on the part of the Investigative Team members who returned the potentially privileged material. But they also indicate that, on more than one occasion, the Privilege Review Team’s initial screening failed to identify potentially privileged material. The Government’s other explanation—that these instances were the result of adopting an overinclusive view of potentially privileged material out of an abundance of caution—does not satisfy the Court either. Even accepting the Government’s untested premise, the use of a broad standard for potentially privileged material does not explain how qualifying material ended up in the hands of the Investigative Team. Perhaps most concerning, the Filter Review Team’s Report does not indicate that any steps were taken after these instances of exposure to wall off the two tainted members of the Investigation Team [see ECF No. 40]. In sum, without drawing inferences, there is a basis on this record to question how materials passed through the screening process, further underscoring the importance of procedural safeguards and an additional layer of review. See, e.g., In re Grand Jury Subpoenas, 454 F.3d 511, 523 (6th Cir. 2006) (“In United States v. Noriega, 764 F. Supp. 1480 (S.D. Fla. 1991), for instance, the government’s taint team missed a document obviously protected by attorney-client privilege, by turning over tapes of attorney-client conversations to members of the investigating team. This Noriega incident points to an obvious flaw in the taint team procedure: the government’s fox is left in charge of the appellants’ henhouse, and may err by neglect or malice, as well as by honest differences of opinion.”).

What happened, we can tell from context and the available inventory, is that after an initial privilege review released material to the investigative team, the investigative team found two individual documents seized from the storage room that might be privileged, and then turned them over to the filter team. That complies, to a T, to the requirements of the law and the warrant (which only required the filter team review stuff from Trump’s office). This is what happens in every single criminal case in the US. But Cannon deemed it as proof of failure, and so used it to require a Special Master review everything anew.

According to her ruling, the government must halt their criminal investigation into 103 stolen government documents with classification marks, 11,179 stolen government documents that lack classification marks, and 1,673 press clippings (she gets these numbers wrong in her order), because 64 sets of documents that the investigative team has not seen yet includes potentially privileged information as well as, “medical documents, correspondence related to taxes, and accounting information” — details that she chose to make public for the first time even while premising the primary grave damage to Trump as leaks to the public.

She won’t let DOJ investigate a crime. But she will let the Office of Director of National Intelligence investigate the damage the crime did.

[T]he Court determines that a temporary injunction on the Government’s use of the seized materials for investigative purposes—but not ODNI’s national security assessment—is appropriate and equitable to uphold the value of the special master review.17

She doesn’t explain how that would work — how the government would (among other things) investigate any damage done by letting uncleared people move these boxes around — without continuing the investigation.

Edelstein: And in addition to the criminal investigation which is obviously a legitimate interest, as the Supreme Court has recognized, there is also the ongoing damage assessment by the intelligence community. This is not an effort that we just undertook. In fact, in that same May 10th letter that I referenced, there is an April communication to Plaintiff’s counsel that emphasizes that the materials had to be reviewed by the FBI in part so that it could coordinate an assessment of the damage that could have resulted from the improper storage of these materials. And if a special master was appointed at this point, that would — and the Government was not able to continue —

THE COURT: So would your position change, for example, if the special master were permitted to proceed without affecting the ODNI’s ongoing review for intelligence purposes but pausing temporarily any use of the documents in criminal investigation? So what I’m saying is no effect on the DNI review, which is ongoing and has been asserted as necessary for national security but then providing a temporary period of time, like I said, for orderly review of the documents seized?

MS. EDELSTEIN: It would not change.

[snip]

BRATT: And I will tell the Court, you know, how it does slow down because in addition to the damage assessment that ODNI is doing, in any retention case, as we call these types of cases, in any illegal retention case under the Espionage Act, we also start looking at, all right, are these documents still classified? So there is a classification review. Classification is different from national defense information under the case law, okay. So even if it is classified, does it contain national defense information even if it is not classified? Does it not contain national defense information? As the Court is aware, we are dealing with over 300 records here. That process has begun. That process needs to continue.

If the Court says only ODNI can look at this for purposes of damage assessment, that is going to interfere with the investigation, and that’s something the Court, I think, has to enjoin us from doing.

Importantly, ODNI cannot do a damage assessment of all the documents stolen by Trump.

That’s because at least three of the classified documents are in the potentially privileged batch. Two are in box 4.

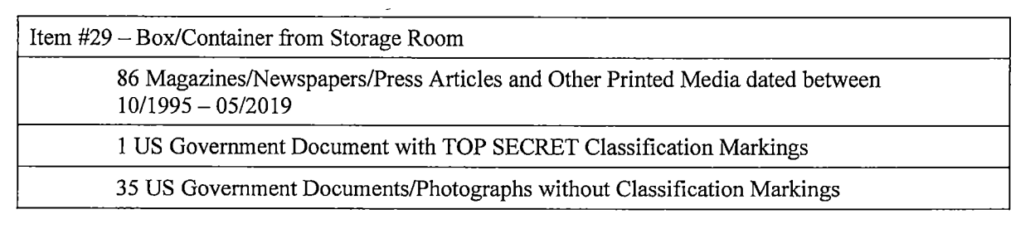

One — a Top Secret document — is in box 29.

The top Espionage experts in the government are investigating this. They will need to be part of any damage assessment. But by taking part in that discussion, they risk tainting the entire investigation because Aileen Cannon thinks that Trump’s privacy interest in a few MAGA hats and tax records his lawyers could have gotten back last week are more important than the 103 classified documents Trump stole.