Thanks to those who’ve donated to help defray the costs of trial transcripts. Your generosity has funded the expected costs of transcripts. But if you appreciate the kind of coverage no one else is offering, we’re still happy to accept donations. This coverage reflects the culmination of eight months work.

There’s accumulating evidence that at least some people — including some key decision-makers — believed the FBI believed that the Alfa Bank tip came from the DNC — and that Andrew DeFilippis has engaged in a lot of coaching to try to make that evidence go away.

The first time FBI Agent Ryan Gaynor testified to John Durham about the investigation into the Alfa Bank anomaly in October 2020, he told prosecutors that the DNC was the source of the allegation.

Q. Okay. So in your first meeting with the government, you — this is October of 2020, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. You told them multiple times that you believed that the Democratic National Committee was the source of the allegations of connections between Alfa-Bank and Russia, correct?

A. Correct, which was wrong.

Q. Okay. But you said that you thought the Democratic party itself was who provided the information, correct?

A. I did say that in the meeting.

That’s even what he has written down in a briefing document he kept in Fall 2016.

At the end of that October 2020 interview, prosecutors threatened Gaynor with prosecution.

His more recent testimony, starting for the first time on May 13, was that Sussmann was representing himself. The reason he now remembers that to be true goes to the heart of Durham’s materiality: it would have mattered if Sussmann was representing the DNC, so he must have been representing himself.

Q. Okay. I want to ask you, first, about testimony that you gave today where you said that when Mr. Moffa told you that Mr. Sussmann was a DNC attorney, you said, “I understood that to mean that he had been affiliated with the Democratic party but that he had come representing himself on the Alfa-Bank allegations.” Do you remember giving that testimony?

A. That was my take-away.

Q. And you gave that testimony that I just read?

A. Yes; that he was a DNC attorney, but that my take-away from that discussion was that he wasn’t there representing the DNC.

Q. When you were asked, “When Mr. Moffa said Mr. Sussmann was an attorney for the DNC, what impression did you come away with?” what did you understand that to mean? And your answer was: “I understood that to mean that he had been affiliated with the Democratic party, but that he had come representing himself,” right?

A. So he’s affiliated with the Democratic party because he was a DNC attorney.

Q. And your impression was he had come representing himself?

A. My take-away from that meeting, what I recall, is that I did not believe that he was there representing the DNC specifically because, had he been, that would have been information that would have impacted it.

This is a tautology: If Sussmann had been representing the DNC it would have mattered so it must be the case that Gaynor believed he was not representing the DNC. It also happens to be the central argument of DeFilippis’ materiality claim.

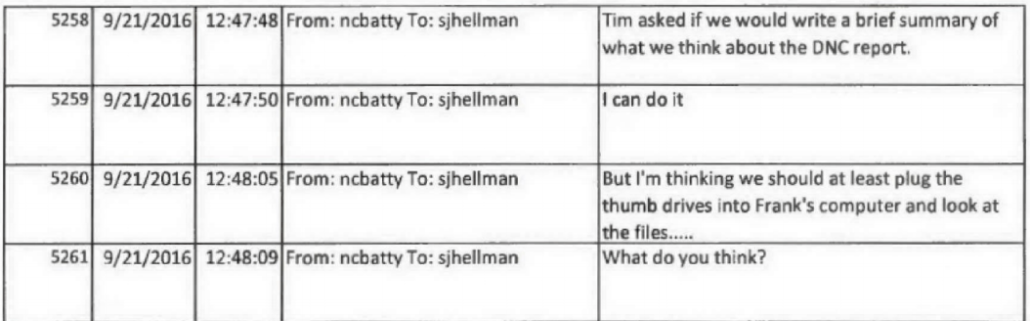

Meanwhile, Scott Hellman — Durham’s star cyber witness — received a text from his boss, Nate Batty (with whom he compared notes before his first interview with Durham), referring to the white paper as a “DNC report” on September 21, 2016, two days after Jim Baker received the materials.

Michael Sussmann lawyer Sean Berkowitz asked Hellman about that the other day. At first, Hellman expressed surprise about that text.

Q. All right. And then, with respect to Stranahan, he asks you and Nate to write a report about the — write a summary of the DNC report. Correct? That’s what it says?

A. That’s what it says in this chat, yes.

Q. And did you understand, sir, that the information had come from a DNC, meaning Democratic National Committee, source?

A. I did not understand that, no.

Q. Did you know what Nate Batty knew about it?

A. I don’t think he knew anything about it.

Q. Did you call up Tim and say, what a second. This is a DNC report? That’s political motivation.

A. No.

Q. Didn’t do anything or it didn’t occur to you?

A. The first time I saw this was two years ago when I was being interviewed by Mr. DeFilippis, and I don’t recall ever seeing it. I never had any recollection of this information coming from the DNC. I don’t remember DNC being a part of anything that we read or discussed.

Q. Okay. When you say, the first time you saw it was two years ago when you met with Mr. DeFilippis, that’s not accurate. Right? You saw it on September 21st, 2016. Correct?

A. It’s in there. I don’t have any memory of seeing it.

Later in Berkowitz’ cross-examination he returned to the text. He asked how it could be that a white paper from a DNC lawyer could be referred to as a DNC report.

Q. And although you were surprised to see it today, it appears that at least somebody, such as Mr. Batty was aware and you were aware that somebody was calling this white paper a DNC report. Correct?

A. I was not aware that anybody was calling it a DNC report, and I don’t believe Mr. Batty knew that either.

Q. But you saw the link message. Right?

A. I did see the link message, yes.

Berkowitz asked Hellman how it could be that he would see a reference to a DNC report and not take from that it was a DNC report. Hellman describes “the only explanation that … was discussed” — which is that it was a typo.

Q. What’s your explanation for it?

A. I have no recollection of seeing that link message. And there is — have absolutely no belief that either me or Agent Batty knew where that data was coming from, let alone that it was coming from DNC. The only explanation that popped or was discussed was that it could have been a typo and somebody was trying to refer to DNS instead of DNC.

Q. So you think it was a typo?

A. I don’t know.

Q. When you said the only one suggesting it — isn’t it true that it was Mr. DeFilippis that suggested to you that it might have been a typo recently?

A. That’s correct.

Q. Okay. You didn’t think that at the time. Right?

A. I did not. I had never seen it or had any memory of seeing it ever before it was put in front of me.

With some prodding, Hellman admitted that when he referred to “discussing explanations,” he meant doing so with Andrew DeFilippis. This exchange was, quite literally, Berkowitz eliciting Hellman to provide an answer that DeFilippis thought up — one necessary to sustain DeFilippis’ narrative — without, at first, admitting it was DeFilippis’ opinion of what the truth must be.

So after DeFilippis threatened Gaynor with prosecution, he came to remember something other than what the note, tying the white paper to DNC lawyer Michael Sussmann, that he used to “refresh his memory” said.

And when faced with the possibility, two years or maybe six after the fact, that Scott Hellman’s epically shitty analysis of the white paper could have been influenced by being told that it was a DNC white paper, Hellman offered up the explanation that DeFilippis offered him.

At least twice, then, under coaching from Durham’s lead prosecutor, key witnesses have come to believe something other than what the documentary evidence suggests.

The fact that DeFilippis has twice coached witnesses to deny any understanding at FBI that this was a DNC tip — whether it was a DNC tip or not — is really telling. That’s because DeFilippis has to try to pitch a nearly unsustainable position: how his single witness to Sussmann’s alleged crime, Jim Baker, can in 2016 have told Bill Priestap the following:

Q. I think you testified yesterday that by this time you were at least generally aware that Mr. Sussmann represented the DNC in connection with hacks; is that right?

A. That’s correct.

Q. And what, if anything, did you say to Mr. Priestap about that?

A. I think I told him like, okay, this is who Michael is. He’s represented the Democratic party in the Russian hack that we were also investigating and/or the Hillary Clinton Campaign. So just, again, to orient Bill to who Michael was. I mean, that’s a serious credential in terms of being a cyber security expert. And then to explain: But in this case he said he’s not appearing on behalf of them. In this case he’s coming in as a good citizen.

And then, in 2018, have told Jim Jordan the following:

Q. Mr. Jordan then says: “And he was representing a client when he brought this information to you or just out of the goodness of his heart? Someone gave it to him and he brought it to you?”

A. In that first interaction, I don’t remember him specifically saying that he was acting on behalf of a particular client.

Q. Did you know at the time that he was representing the DNC in the Clinton campaign?

A. I can’t remember. I had learned that at some point. I don’t, as I said — as I think I n said last time, I don’t specifically remember when I learned that — excuse me — so I don’t know that I had that in my head when he showed up in my office. I just can’t remember.

Q. Did you learn that shortly thereafter if you didn’t know it at the time?

And then testify last week this way.

Q. Okay. Number two, did you know on the September 19th, 2016 meeting that Mr. Sussmann had been representing Hillary For America’s campaign and the DNC in connection with the hack investigation. Did you know that on September 19th when he met with you?

A. Sitting here today, I think the answer is, yes, I did know that by that point in time.

Q. I’ve written down, “yes, DNC and HFA and hack”. I want to be really clear. You’re not saying that he said that in the meeting. correct?

A. Correct.

Q. And you’re not saying he said he was there on behalf of them? You’re just saying that in your mind you knew that he had been acting as a lawyer for those two entities in connection with the hack. Correct?

It’s not just a question of whether Baker will be a credible witness, though his wildly changing claims about the DNC are among the reasons why his testimony is not credible.

It’s also that Durham wants to point to Sussmann’s failure, a year earlier in a Congressional hearing, to offer up his ties with the Democrats as proof he was lying. But Durham is treating Baker’s failure to do so in the same situation as an innocent mistake. For his single witness to be credible, DeFilippis has to find a way to excuse Baker’s failure to offer that up in a far more direct question while pointing to Sussmann’s failure to offer it up as proof of guilt.

He has to do so to defend his prosecutorial decisions, too. Given how much stake DeFilippis has placed on Baker sharing with Priestap that he knew Sussmann represented the Democrats, it makes it far less credible that Baker didn’t knowingly lie to Jordan. Especially given the way Baker responded to a Berkowitz question, suggesting that perhaps he hadn’t been truthful with Jordan, but instead was “careful.”

Q. And when you gave voluntary information to Congress, you understood that you were under oath?

A. I don’t think I was under oath, but I understood that it’s a crime to make false statements to Congress.

Q. So you tried to be as careful as you could. Correct?

A. I tried to be as careful as I could in that environment, yes, sir.

Q. You tried to be as truthful as you could?

A. (No response)

Q. Tried to be as truthful as you could?

A. Yes, sir.

Sussmann’s team is going to argue that there are a long list of people against whom there is far better evidence for false statements or perjury charges than him, with the single difference being that the other people were willing to tell the storytale DeFilippis is using prosecutorial resources to tell. And the first person on that list — it makes me sick to my stomach to say — is Jim Baker.

Finally, it’s a matter of materiality. DeFilippis has to find a way for it to be the case that his single witness knew when he met with Sussmann that Sussmann was a DNC lawyer (because Bill Priestap’s notes reflect that), but didn’t view that to be material to everything that happened next.

And the only way to sustain that rickety narrative is to ensure that no one else — not even the people using documentary proof reflecting a belief that this was a DNC report to refresh faded memories — understood that the white paper came from the DNC.

Thus far, Sussmann’s cross-examination has elicited evidence that at least three witnesses changed their testimony after interviews with DeFilippis, adopting a “memory” that conflicts with the documentary record with regards to whether the FBI believed the white paper to be associated with the DNC.

OTHER SUSSMANN TRIAL COVERAGE

Scene-Setter for the Sussmann Trial, Part One: The Elements of the Offense

Scene-Setter for the Sussmann Trial, Part Two: The Witnesses

With a Much-Anticipated Fusion GPS Witness, Andrew DeFilippis Bangs the Table

John Durham’s Lies with Metadata

emptywheel’s Continuing Obsession with Sticky Notes, Michael Sussmann Trial Edition

Brittain Shaw’s Privileged Attempt to Misrepresent Eric Lichtblau’s Privilege

The Methodology of Andrew DeFilippis’ Elaborate Plot to Break Judge Cooper’s Rules

Jim Baker’s Tweet and the Recidivist Foreign Influence Cheater

That Clinton Tweet Could Lead To a Mistrial (or Reversal on Appeal)

John Durham Is Prosecuting Michael Sussmann for Sharing a Tip on Now-Sanctioned Alfa Bank

Apprehension and Dread with Bates Stamps: The Case of Jim Baker’s Missing Jencks Production