Scene-Setter for the Sussmann Trial, Part One: The Elements of the Offense

Thanks to those who’ve donated to help defray the costs of trial transcripts. Your generosity has funded the expected costs. If you appreciate the kind of coverage no one else is offering, we’re still happy to accept donations for this coverage — which reflects the culmination of eight months work.

In the first of what will be a number of “scene-setters” for the Michael Sussmann trial next week, Devlin Barrett makes two significant errors. First, he misrepresents what Sussmann said in a text to James Baker on September 18, 2016.

In a text message setting up the meeting, Sussmann claimed he was not representing any particular client in bringing the matter to the FBI’s attention.

Here’s what the text says:

Jim – it’s Michael Sussmann. I have something time-sensitive (and sensitive) I need to discuss. Do you have availibilty [sic] for a short meeting tomorrow? I’m coming on my own – not on behalf of a client or company – want to help the Bureau. Thanks.

[I’m unclear whether the misspelling of “availability” is Sussmann’s or Durham’s.]

The distinction between “representing” and “on behalf of” will be a core issue litigated in this trial (as I’ll lay out below), which makes Barrett’s sloppiness affirmatively misleading.

Second, Barrett serially accepts Durham’s framing — that the cybersecurity researchers who started identifying the Alfa Bank anomaly months before Rodney Joffe ever talked to Michael Sussmann were doing “campaign research.”

The two-week trial will delve into the murky world of campaign research, lawyers and the role the FBI played in that election, as Trump and Hillary Clinton vied for the presidency, and federal agents pursued very different investigations surrounding each of them.

[snip]

Prosecutors signaled this week that they plan to call a host of current and former law enforcement officials to describe how the FBI pursued the Alfa Bank accusations, and to paint Sussmann as part of a “joint venture” that included Joffe, Clinton’s campaign, research firm Fusion GPS and cybersecurity experts.

[snip]

Cooper, however, has limited how deeply Durham’s team may go into the particulars of any alleged joint venture among Democratic operatives, ruling that he will not allow “a time-consuming and largely unnecessary mini-trial to determine the existence and scope of an uncharged conspiracy to develop and disseminate the Alfa Bank data.”

Barrett does this in spite of the fact that Durham has repeatedly said the only evidence he has supporting his joint venture conspiracy theory (even assuming it were illegal) is billing records. While Barrett cites the gist of Cooper’s ruling excluding Durham’s unsubstantiated claims of a “joint venture,” he doesn’t quote Cooper noting that, “some evidence suggests that Fusion GPS employees had no connection to the gathering or compilation of the Alfa Bank data.” Effectively, an experienced DOJ reporter has fallen for Durham’s use of unsubstantiated materiality claims to frame a prosecution that didn’t charge the underlying conspiracy. That’s a real disservice to readers who don’t know the difference between uncharged materiality claims and a charged conspiracy.

So here’s my effort to explain to newbies what the trial is about. Durham has to prove that:

- Michael Sussmann said what Durham claims Sussmann did to James Baker on September 19, 2016

- What he said was a lie

- The alleged lie was material to the functioning of the FBI

Durham has to prove that Sussmann said what Durham claims he did on September 19, 2016

From the start, Durham has been uncertain what lie Sussmann told. As Sussmann pointed out in a motion for a bill of particulars right from the get-go, at various points in the indictment, Durham claimed that Sussmann’s lie was:

- “that he was not doing his work on the aforementioned allegations ‘for any client'” (one)

- “that he was not acting on behalf of any client” (one, two)

- that he was not “acting on behalf of any client conveying particular allegations concerning a Presidential candidate” (one)

That is, repeatedly in the indictment, Durham was conflating the “work” of chasing down the allegations (which is not at issue in this prosecution at all) with the meeting where Sussmann shared those allegations with the FBI. The last formulation is what Durham charged, but as we’ll see, unless Durham supersedes this indictment today, he may have problems with that formulation as well.

Almost six months after Durham charged Sussmann for lying about sharing allegations on September 19, he got rock-solid proof — a text from Sussmann to Baker that Durham only found because Sussmann kept asking Durham to go back and look for these records — that Sussmann said, he was “coming on my own – not on behalf of a client or company – want to help the Bureau,” on September 18.

That rock-solid proof actually presents two problems for Durham. First, it raises the possibility that, even if the jury decides this was a lie, Durham can only prove Sussmann said it on September 18, not September 19. But the text also suggests what Sussmann may have meant by “on behalf of:” who benefits. He was not seeking a benefit for a client, he was trying to benefit the FBI.

That interpretation is consistent with what Sussmann said under oath in 2017, and it is an interpretation that Durham did not test before he charged Sussmann.

I was sharing information, and I remember telling him at the outset that I was meeting with him specifically, because any information involving a political candidate, but particularly information of this sort involving potential relationship or activity with a foreign government was highly volatile and controversial. And I thought and I remember telling him that it would be a not-so-nice thing ~ I probably used a word more stronger than “not so nice” – to dump some information like this on a case agent and create some sort of a problem. And I was coming to him mostly because I wanted him to be able to decide whether or not to act or not to act, or to share or not to share, with information I was bringing him to insulate or protect the Bureau or — I don’t know. just thought he would know best what to do or not to do, including nothing at the time.

And if I could just go on, I know for my time as a prosecutor at the Department of Justice, there are guidelines about when you act on things and when close to an election you wait sort of until after the election. And I didn’t know what the appropriate thing was, but I didn’t want to put the Bureau or him in an uncomfortable situation by, as I said, going to a case agent or sort of dumping it in the wrong place. So I met with him briefly and

[snip]

so I told him this information, but didn’t want any follow-up, didn’t ~ in other words, I wasn’t looking for the FBI to do anything. I had no ask. I had no requests. And I remember saying, I’m not you don’t need to follow up with me. I just feel like I have left this in the right hands, and he said, yes. [my emphasis]

As has been explained over and over, Jim Baker’s testimony about what Sussmann said to him on September 19 (as opposed to what Sussmann texted him on September 18) has been all over the map:

- An October 3, 2018 Baker interview Baker said he didn’t recall Sussmann saying he was there on behalf of Hillary.

- An October 18, 2018 Baker interview Baker said that in that first meeting, he did not recall Sussmann saying he was acting on behalf of a specific client.

- A July 15, 2019 Baker interview Baker said Sussmann was sharing information from cybersecurity experts.

- A June 2020 Durham interview Baker said it did not seem like Sussmann was representing a client (and he was not aware that Sussmann represented the DNC.

- Three more Durham interviews with Baker on this subject that align with the indictment.

Durham will argue that he got Baker’s testimony to match what he, Durham, claims to be sure is the truth by refreshing his memory with notes that Bill Priestap and Trisha Anderson took, the former when Baker told him about the meeting immediately afterwards and the latter in circumstances that are less clear.

The Priestap notes say four things:

- Represent DNC, Clinton Foundation etc

- Been approached by prominent cyber people

- NYT, Wash Post, or WSJ on Friday

- [Written slantways for reasons Priestap could not explain] said not doing this for any client

The Anderson notes say two things:

- No specific client but group of cyber academics talked with him about research

- Article this Friday, NYT/WPost [the notes fade out]

None of those notes say “on behalf of,” Anderson’s don’t address whether Sussmann offered up the claim or not, and Priestap seems to have written “not doing this for any client” after the fact, as if it wasn’t part of Baker’s initial telling.

None of those notes make it clear what part of the information Baker passed on came from the meeting itself and what part came from the text he had received the day before (and indeed, Priestap’s slantways note may suggest the detail about a client could have come later). Durham only has a refreshed memory of what Baker knew by September 19, not which parts he learned on September 18 and which he learned on September 19.

Literally six months after indicting Sussmann, Durham gave him different sets of notes recording how Andy McCabe explained the allegations to Dana Boente on March 6, 2017.

One set, from Tashina Gauhar’s notes, says this:

“Attorney” Brought to FBI on behalf of his client

Also advised others in media > NYT

Another set, from Mary McCord’s notes, says this:

First brought to FBI att by atty

[snip]

Attorney brought to Jim Baker + d/n say who client was. Said computer researchers saw the [activity?]. Said media orgs had the info, including NY Times.

These notes admittedly reflect what the FBI came to understand, possibly in the September 19 meeting, possibly hours after the September 19 meeting, possibly days, possibly months. But as McCord recorded it, the emphasis remained on the computer researchers and the NYT. That emphasis is important for materiality questions.

Durham has to prove what Sussmann said was a lie

Next, Durham has to prove that what Sussmann said was an intentional lie.

Probably, Durham will use the formulation Sussmann sent in his September 18 text, “I’m coming on my own – not on behalf of a client or company – want to help the Bureau,” since that’s the only thing he has real proof of. This is why Sussmann tried to nail down Durham on what “on behalf of” shortly after being charged. Because it could mean, “on the orders of,” “for a client I am retained by,” or “seeking some benefit or ask for.”

But Sussmann’s explanation, “want to help the Bureau,” tied as it is to some benefit for the FBI, presents new problems for Durham. As noted above, that’s precisely what Sussmann said in sworn testimony back in 2017, when he had no reason to believe there would ever be a special prosecutor checking his claims and at a time he no longer had that text to check. Sussmann framed it in terms of giving the FBI maximal flexibility during campaign season.

Importantly, Sussmann did take steps to help the Bureau, by (with Joffe’s assent), helping the FBI kill the story the NYT was close to publishing. Which is another thing Sussmann described when he testified under oath in 2017 and another thing Durham didn’t bother to investigate before indicting.

I just wanted to tell you about a phone call that I had with him 2 days after I met with him, just because I had forgotten it When I met with him, I shared with him this information, and I told him that there was also a news organization that has or had the information. And he called me 2 days later on my mobile phone and asked me for the name of the journalist or publication, because the Bureau was going to ask the public — was going to ask the journalist or the publication to hold their story and not publish it, and said that like it was urgent and the request came from the top of the Bureau. So anyway, it was, you know, a 5-minute, if that, phone conversation just for that purpose.

Along with the September 18 text showing Sussmann told Baker he wanted to help the FBI, there were several texts reflecting that when Baker asked Sussmann for the name of the outlet that was reporting on the Alfa Bank allegations, Sussmann told Baker he had to ask someone before sharing the name.

Those text messages include, among other things, texts indicating that Mr. Sussmann asked to meet with Mr. Baker in September 2016 not on behalf of a client but to help the Bureau; texts indicating that Mr. Sussmann told Mr. Baker he had to check with someone (i.e., his client) before giving him the name of the newspaper that was about to publish an article regarding the links between Alfa Bank and the Trump Organization; and other texts, including a copy of a tweet that then-President Trump posted regarding Mr. Sussmann.

Then, Sussmann and Baker spoke on the phone several times on September 21 and 22.

Mr. Sussmann and Mr. Baker also had several phone conversations over the course of that week, including on Wednesday, September 21 and on Thursday, September 22.

We’ll learn more details at the trial, but we know that Baker and Bill Priestap called the NYT and got them to kill the story.

One reason this is important is because — as Sussmann’s attorney noted in a recent hearing — this is the opposite of what Sussmann would have done if he was working on behalf of the campaign.

We expect there to be testimony from the campaign that, while they were interested in an article on this coming out, going to the FBI is something that was inconsistent with what they would have wanted before there was any press. And in fact, going to the FBI killed the press story, which was inconsistent with what the campaign would have wanted.

The decision to go to the FBI contravened Hillary’s best interest.

The other reason those exchanges are important is because, as Sussmann pointed out, the best explanation for how Andy McCabe (that “top of the Bureau” that decided to take steps to kill the story) came to learn that Sussmann did have a client was via those exchanges.

The FBI could not have come to that belief based on conversations they had with Mr. Sussmann after his phone calls with Mr. Baker the week of September 19, 2016, because the FBI chose not to interview Mr. Sussmann about the information he provided to Mr. Baker, and the FBI chose not to ask Mr. Sussmann about or interview the cyber experts whom Mr. Sussmann identified as the source of the information he shared with the FBI.

Indeed, that timeline may explain why Baker’s memories about this are so inconsistent: because what Sussmann told him on September 18, what he told him on September 19, and what he told him on September 21 have all blended into one.

In any case, though, the best evidence suggests the FBI probably learned Sussmann had a client within three days of the time Sussmann first brought the allegations to the FBI (because that was the last he spoke with the FBI). That undermines Durham’s claim that Sussmann was hiding some big conspiracy. Within days, he appears to have made it obvious he did have a client.

Durham has to prove the alleged lie was material to the functioning of the FBI

I’m not going to get too far into the work Durham will have to do to prove that Sussmann’s lie — if he can prove what Sussmann said, if he can prove Sussmann said it on September 19 and not September 18, and if he can prove it really was a lie — had the ability to affect the decisions the FBI could have made.

Sussmann has many ways to attack Durham’s materiality argument. He’ll do so by proving:

- FBI knew he represented the Democrats (indeed, that’s what Priestap’s notes say)

- FBI knew of his ties to Joffe

- His characterization that this came from cybersecurity experts was true

- After the Franklin Foer piece was published, a separate FBI Agent attempted to open an investigation (showing what would have happened if Sussmann had not shared the information and just let NYT publish)

If I were him, I would also point to all the evidence (including from the March 2017 notes) that what most mattered to the FBI was not whom his client was but that the NYT was going to publish this.

But, given the timeline laid out by Sussmann’s texts and calls with James Baker, I’d make one more point. All the evidence suggests that FBI knew he had a client by September 22 — probably by September 21.

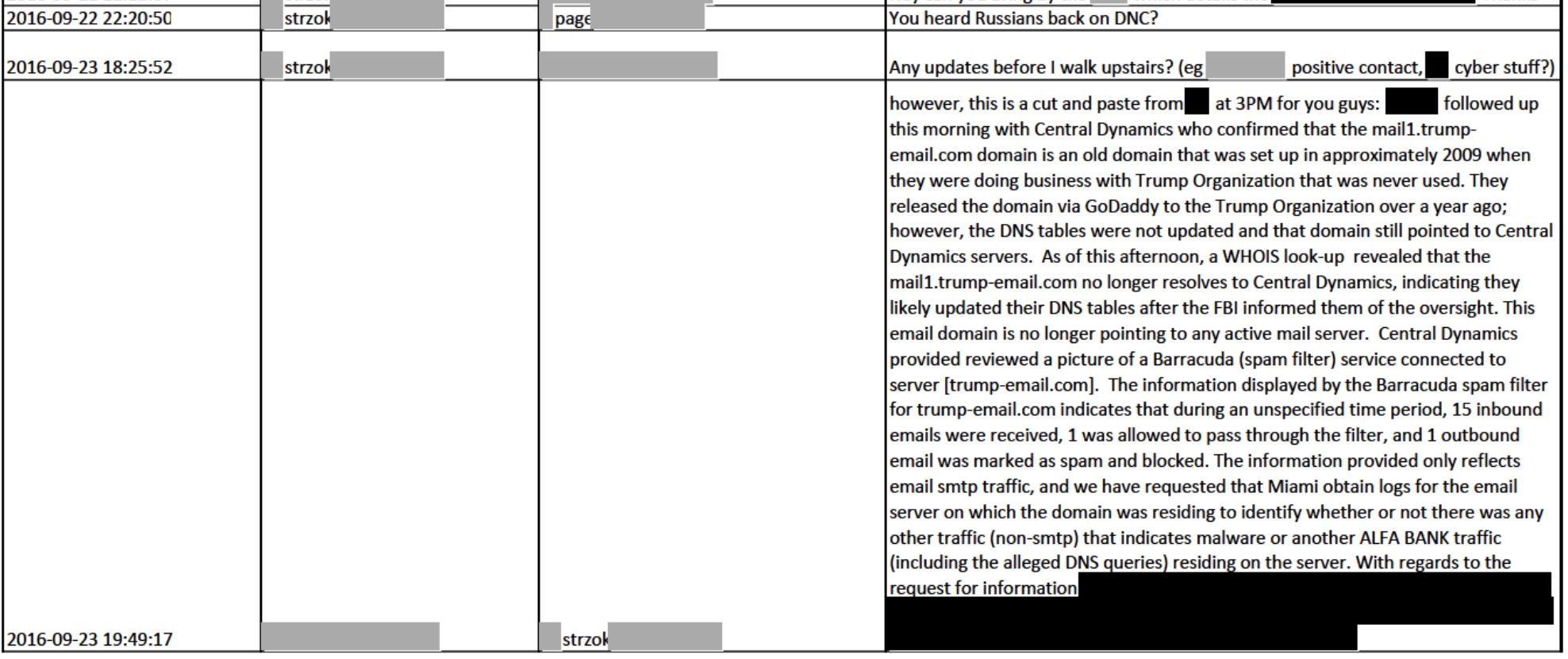

The FBI Agents who will describe the steps they took will apparently describe making a second call to Cendyn on September 23.

That is, the timeline will show that FBI learned Sussmann had a client before they even spoke to Cendyn a second time.

If Sussmann’s client or clients mattered, the FBI learned about them so early in the process that it would not have affected the overall investigation.

Durham’s tactical retreat

I know a lot of people think Durham has a slam-dunk case with that September 18 text, but that’s simply not the case — though as always, you never know what a jury is going to decide.

But I think that Durham is already planning a tactical retreat.

As Sussmann noted in a recent filing summarizing conflicting views on jury instructions, Durham’s indictment describes Sussmann’s alleged lie this way:

[O]n or about September 19, 2016, the defendant stated to the General Counsel of the FBI that he was not acting on behalf of any client in conveying particular allegations concerning a Presidential candidate, when in truth, and in fact, and as the defendant knew well, he was acting on behalf of specific clients, namely, Tech Executive-1 and the Clinton Campaign.

Never mind that Durham characterized the allegations as pertaining to “a Presidential candidate,” which presents other problems for Durham, he has also accused Sussmann of lying about having two clients.

Mr. Sussmann proposes modifying the last sentence as follows, as indicated by underlining: Specifically, the Indictment alleges that, on or about September 19, 2016, Mr. Sussmann, did willfully and knowingly make a materially false, fictitious, and fraudulent statement or representation in a matter before the FBI, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(2), namely, that Mr. Sussmann stated to the General Counsel of the FBI that he was not acting on behalf of any client in conveying particular allegations concerning Donald Trump, when, in fact, he was acting on behalf of specific clients, namely, Rodney Joffe and the Clinton Campaign.5 The government objects to the defense’s proposed modification since it will lead to confusion regarding charging in the conjunctive but only needing to prove in the disjunctive.

4 Authority: Indictment.

5 Authority: Indictment.

Durham’s language about “conjunctive” versus “disjunctive” will likely be the matter for heated debate next week. Particularly in the wake of Cooper’s decision that the materials from the researchers won’t come in as evidence, Durham seems to be preparing to prove only that Sussmann lied about representing Hillary, and not about Joffe. Sussmann, meanwhile, seems to believe that Durham will have to prove that his alleged lie was intended to hide both alleged clients.

The problem with Durham’s fall-back position is that if Sussmann really were representing Hillary at that FBI meeting, he wouldn’t have killed the NYT story that would have helped her campaign.

Update: Corrected date on Sussmann’s HPSCI interview, which was 2017.

Key “not” missing, Marcy:

‘That he was *NOT* “acting on behalf of any client conveying particular allegations…”’

Typo alert ::

You say in the front page of the post “John Durham will have to prove thatDurham has to prove that” with a phrase duplicated.

Wow. There is a lot of parsing in this post. Good parsing, but parsing nonetheless. Durham’s case is based on very slim reeds, but he has nothing to lose should his case fail. He is in good with the frothy right and they will literally sustain him should he need it. Sussman, on the other hand, has plenty of evidence to back his stance, but if his liberty depends on courtroom wrangling on the meaning of “represents” vs “on behalf of,” that, too, is a slim reed. As you say, “as always, you never know what a jury is going to decide.”

Zirc

“He is in good with the frothy right and they will literally sustain him should he need it. ”

They have no loyalty. If he screws this up, they’ll dump him, find a new vehicle to chase the 2016 demons, and leave him stewing in a closet not getting his calls returned.

Opponents of these people don’t make enough of this dynamic.

Maybe. But the frothy right has ways of finding scapegoats when things don’t go their way. If Sussman were to be acquitted or the case dismissed, Cooper could be made to be the villain rather than Durham.

Zirc

They turn on their own loyalists at the drop of a hat.

If they decide to switch avenues of attack due to this fizzling out, they will absolutely demonize Durham based on his work during Democratic administrations, when they aren’t gaslighting about of the hopes and dreams they loaded on him.

The dangers of collaboration aren’t secret, and they should be a much bigger deal.

I don’t see the right turning on Durham, when he loses, they’ll use it as proof of the deep state or a cabal of pedophiles in the jury pool. It doesn’t have to make sense. Durham gave them ammunition, for them that’s more important than Sussman.

I agree with Njrun, adding: The frothers are unlikely to turn on Durham before the mid-term election, not the least because they have incentive to use the October Danchenko trial to damage Democrats. Electorally speaking, the Durham role/ fate that matters to frothers is how the SC [OSC?] could effect the 2024 elections.

The conservative Catholic political hard core would not likely reject Durham if he loses.

Agreed. Notwithstanding the likelihood of Merrick Garland terminating the Special Counsel in the event of a not guilty verdict (IMO), the frothy right, as you say, has no time for losers these days. See: Rudy Giuilani. Durham pretty much loses everything, right up to his dignity and reputation, in the event of a not guilty verdict. I believe that is why he is trying this case in the manner he is doing so. He and his team get cancelled

It all comes down to how replaceable they think he is — and I honestly don’t see what makes him particularly special for them. A reemergence of Ebola, Al Franken gets caught as a cannibal, anything else that gets headlines for them and he’s toast.

One of the key messages of opponents of the GOP should be warning potential collaborators that the Devil never keeps his end of the bargain. Sooner or later Durham becomes Saul Goodman turned into Gene Takavic, running a Cinnabon and always looking over his shoulder.

All the distractions aside, the jury will be able to easily understand there were only two people “in the room where it happened, in the room where it happened.”

After all the motions and discovery and billing records, and notes, and motive, and DNS data, and joint ventures, there are still just two people “in the room where it happened, in the room where it happened.”

If jury believes Baker, then Sussmann is going to have a steep hill to climb; all this other stuff won’t really matter.

Baker has a lot of power to shape impressions depending on how strongly he holds to believing vs. just not recalling things said or unsaid in Sept. 19; probably so much so he can still give the case to either Durham or Sussmann.

Does “on or about September 19” include September 18 or 20? Don’t most pleadings/ indictments include that phrase so as to be more inclusive as to dates something occurred?

Lying to the FBI seems to be a very broad category. Why would anyone ever talk with them if the risk of a misstatement could be criminal upon a whim. I expect the defense costs are already many hundreds of thousands of dollars. Expensive chat.

“Why would anyone ever talk with them if the risk of a misstatement could be criminal upon a whim.”

Do you have any idea about the history of this place? Or is this a sneaky attempt to be clever?

One of the cornerstones of Russian pre-invasion propaganda was telling Ukrainians and their allies that resistance was too risky and to do absolutely nothing. It seems odd to be repeating that kind of superficial savvy messaging about a guy who had every reason to be alarmed about a massive Russian campaign against the US in 2016.

I am awfully curious how the NY Times will deal with the issue. They’ve never wanted to account for the “No Clear Link to Russia” article.

I can see three ways they can compound their massive screwup. One is they will ignore the importance of the request to hold off on publishing to Sussman’s defense.

Another is put the focus on the fact that they ignored the FBI’s request to hold off on publication and went ahead and confirmed the existence of the FBI as some kind of journalism morality play, which conveniently memory holes all of the times they shelve reporting.

The most cynical take would be to recommit to the bogus premise of the “No Clear Link” article and attack Sussman’s defense on this point by claiming there really were no grounds for going to the FBI. They may claim that he must have been partisan because they don’t want to expose how badly Times editors injected their biases into that article, or how it all really came about.

A lot will depend on who is called (and not called), and what they say. If the government’s entire case, at the end of the day, is a pile of notes, many from third parties who did not speak to Sussman directly… I’m not sure that would or should survive a summary judgment motion.

But the number of potential defense witnesses that the government seems eager to keep off the stand, is surprising.

This is not a civil case, it is criminal. There is no “summary judgment”. And “summary judgment” happens before trial, not during it, even in a civil case. Please do not try to make people here stupid, which you continually do.

Fine.

Motion for directed verdict then, or judgment of acquittal, or whatever “your honor, the case the prosecution just presented was utter crap, no reasonable jury can find my client guilty based on that shit-show, and the charges should be thrown out post-haste without further wasting the jury’s time” is called under the rules of federal criminal procedure.

So, make an ignorant argument in the plural and hope it flies in a real court? That is your plan?

Dude. I’m still not sure why I’ve gotten on your bad side. IANAL (obviously), so forgive me for confusing criminal and civil procedure. In federal criminal court, after the prosecution presents its case, does the defense have the option to move for an acquittal, or a dismissal, or a directed verdict, or other some way of ending the case then and there, should the prosecution have presented a case which is complete BS?

I’m thinking that proving Sussman guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, would at minimum require someone, most likely Baker, to actually take the stand and testify that yea verily, Sussman told a whopper in his presence, and that he was led to believe that Sussman had no client, and that this was material to his (or others in the bureau) actual decisions regarding the case; and that Baker then would need to survive cross-examination with his credibility intact. Given that he’s told different people different things concerning an event that took place six years ago, he might have a hard time explaining why THIS version of events is the correct one.

I’m thinking that there is a decent chance that when the prosecution rests, there won’t be enough evidence (not tainted by hearsay) for a reasonable jury to convict. I could be wrong–Baker might turn out to be a strong witness for the prosecution who is certain that Sussman lied about his client(s), and further claim that of course this is material. But I don’t think it’s likely based on what I’ve seen.

And if that does turn out to be the case, can the defense get the charges thrown out before it goes to the jury?

Dude. Let me tell you why you’re on my shit list.

– You are rarely concise.

– You do little of your own homework, expecting contributors/moderators to spoon feed you.

– Your comments are a form of concern trolling which falls under the “Just Asking Questions” format while DDoSing threads.

– You can’t take a hint that you’re sucking up moderators’ time.

For starters. bmaz may have more to add or he may err on the side of his own personal style of concision.

Obtuseness is not the sincerest form of flattery.

The errors by WaPo reporter Devlin Barrett lead me to two remarks. First, we are very lucky to have emptywheel!

Second, there are some real weaknesses even at the top of journalism. Mr. Barrett is clearly at the top. He’s a DOJ/FBI reporter at a leading outlet and wrote a book about similar issues. Yet he doesn’t understand the basics. My experience trying to help out reporters on three kinds of issues, legal (where I know a little), economics and technology (both where I know a lot) is that they very rarely understand the basics. Technology reporters who write for the tech trade press are the sole exception. The economics reporters are the weakest, since sometimes they have to be a little bit quantitative to succeed, e.g. they might have to know how percentages work. Many reporters have no STEM training that took root.

How to fix this? This wonderful website is part of the answer — call them on their ignorance. Mr. Barrett’s story reveals structural problems though. It is a lot more fun for reporters and readers to dive into the murky world of “campaign research” and all the shadowy figures that work there. Here “shadowy” just means other reporters haven’t written about them much yet. There are inherent pressures in journalism toward the shallow and the sensational. Adding readers/viewers who call them on this can help, as my tech trade press example shows.

Then, of course, there is the other problem that journalists not at all interested in accuracy can thrive in our current environment. I sort of wish that the top reporters were helping to call them out more.

Somewhat related:

Years ago I was the marketing coordinator for the Sacramento Bee (McClatchy’s then flagship paper). Every reporter – and anyone else who wanted to – received a lesson called “Mathematics for Journalists”. It was a tremendous help in deciphering press releases and quotes from anything related to economics. It’s why I still know a median from a mean.

This seems like a great idea! Great that the Bee (super paper) implemented it.

But I’ve talked to 75 or so reporters about econ and you could count the ones who had basic numeracy on one hand.

Barrett is at the Times now.

Auto-correct: Devlin Barrett seems to be everywhere now. His byline is still at Post but joins others at NYT–on the same day.

I mentioned this in a reply on Twitter recently, but if Durham tries to backtrack and say Sussmann only lied about representing Hillary…all Sussmann’s lawyers have to do is point out that Sussmann *only* asked Joffe for permission to share the reporters name. If Sussmann was also representing Hillary in the FBI meeting, he would need to ask her for permission too.

Mmm, then I’d ask – What would happen if Hillz showed up at this trial and testified on rebuttal or direct, that Durham is full of it?

Has Durham even interviewed Hillz?

Baker was the recipient of the alleged false statement and is on the witness list, so couldn’t Sussman ask him whether the alleged statement would have affected what he subsequently did? Assuming he says no, wouldn’t that blow up the materiality aspect?

That’s a lot of weight to pin on an assumption; don’t ask a question you already don’t know what the answer will be. Baker was lead counsel for FBI. I think your chance of getting a “yes” out of him would be a lot higher, in which case you’d completely shoot yourself in the foot.

But if Baker says “Yes, it affected his decision”, but also has to admit he knew within days of the conversation that Sussmann had a client who was hostile to Trump, won’t the defence have Baker admit what he would have done differently? Because everything that followed from Sussmann’s tip was antithetical to HRC’s interests.

So if he says “Yes,” he’s saying…what exactly? How did Sussmann’s alleged lie benefit Sussmann or his purported client? As things worked out, the ‘lie’ only benefited two entities – Trump’s campaign, and the FBI. Are we supposed to believe that had Sussmann told Baker that he did have a client and that he was representing them when he gave Baker the tip off, that Baker would have (a) let the NYT story run as planned and (b) launched a full blown investigation into the Russia-Trump links?

I think Baker is at least risking looking like a complete idiot on the stand, and at worst, risking being accused of perjury or something like that (IANAL please don’t hurt me).

Am I missing something, that getting Baker to say it *would* have made a difference would somehow work out well for him?

“Oh baby, don’t hurt me

Don’t hurt me No more (whoa, whoa)” https://youtu.be/HEXWRTEbj1I

Baker is not on the witness list.

Bill Priestap is, who was closer to the investigation.

Lol.

In your post, James Baker is on the prosecutor’s witness list, 4th from the top. Is that a different James Baker (based on the number of wikipedia entries this seems entirely possible)? Bill Priestap is also on the prosecutor’s list.

https://www.emptywheel.net/2022/05/10/the-witness-list-for-the-michael-sussmann-trial

My error: I thought you were asking about McCabe, whom Cooper is wondering why he’s not on the witness list.

Apologies.

My point though is that Baker just handed this off, first to Priestap, who handed it off to agents in Chicago. The Agents in Chicago will be the ones who explain what they did.

No problem.

“But if…”

Durham _already_ knows the substance of Baker’s testimony, and if Baker is going to testify that any lie by Sussmann was not material then Durham wouldn’t be calling him as witness for prosecution. Additionally the FBI is not solely Baker, nor was Baker leading or investigating on behalf of FBI; whether any lie if it occurred was or wasn’t material to Baker’s decision-making doesn’t mean it’s the same thing as being (or not being) material to the FBI’s investigation.

“… what Sussmann said under oath in 2018, …” – The date on the linked document is Monday, December 18, 2017

TY. Fixed.

Barrett’s Wash Post article says “[Sussmann’s attorneys] told U.S. District Judge Christopher Cooper there are 327 FBI emails from the period in question that, they say, show various FBI officials understood Sussmann had clients who were Democrats. The judge has signaled he is willing to allow some of that evidence but doesn’t want to spend the time it would take to read hundreds of emails to the jury.”

Shouldn’t the prosecution have to stipulate that there were 327 (or X) number of emails showing the FBI understood Sussmann had Democratic clients?

This shows Sussmann emailed “not on behalf of a client,” because he correctly presumed the FBI knew he had Democratic clients, so he wanted to clarify his motive for coming forward. The alleged lie shows Sussmann was coming forward as a patriotic American.

Damn, Marcie W,

I would be so ignorant without you! Thank you forever, for helping me understand how the legal sausage factory tries — and so often fails — to manufacture justice; or in cases like Durham’s, tries to manufacture evil simulacrums of justice.

With 25 years as an editor behind me, I’ve no comment on substance, only a small note on style.

Where you now say “If Sussmann’s client or clients mattered, the FBI learned so early in the process that it would not have affected the overall investigation,” I wonder if you might not, for the sake of absolute clarity, better say something like:

If Sussmann’s client or clients mattered, the FBI learned [about them] so early in the process that it would not have affected the overall investigation.

You are my hero. I’m trained to nitpick. I wish I weren’t, but it’s the momentum I’m stuck with after 25 years of editorial training; and then when I see you nitpick at such a high level, my own petty grammarian nitpick expertise wants to believe nitpicking can be important — that nitpicking can be a contribution.

You rock, I’m drunk, never mind.

TY. Always happy to make things more understandable.

I’m thinking about this snippet from the post:

“I’m coming on my own – not on behalf of a client or company – want to help the Bureau,” since that’s the only thing he has real proof of. This is why Sussmann tried to nail down Durham on what “on behalf of” shortly after being charged. Because it could mean, “on the orders of,” “for a client I am retained by,” or “seeking some benefit or ask for.”

*********************************

I think there’s another possibility. As lawyers use it, “on behalf of,” could also mean in place of someone (usually their client). This is plausible in context, because Sussman starts by saying “I’m coming on my own.”

In other words, there is a fourth possible innocent explanation for this statement.

Fair point.