John Durham Says Election-Hack Victims Should Wait Until After the Election to Report Tips

Even as Russia assaults a peaceful democracy (which invasion, in a separate filing, Durham calls, “recent world events in Ukraine”), John Durham suggests that a political campaign victimized by Russia should expect to wait until after the election before the FBI opens an investigation into a cybersecurity anomaly potentially implicating her opponent.

Durham even asserts that such a cybersecurity anomaly is not a cybersecurity matter, but instead a political one.

Almost six years after Trump’s request, “Russia are you listening,” was met with a renewed Russian attack on Hillary Clinton, John Durham continues to treat Hillary’s attempts to run a campaign while being attacked as a greater threat than that nation-state attack by Russia.

Durham’s latest contortions come in a response to Micheal Sussmann’s motion to dismiss the indictment.

Sussmann argued that the alleged lie he told (motions to dismiss must accept the alleged facts as true), could not have affected the single decision facing the FBI when he shared information about a DNS anomaly: whether to open an investigation or not.

Following the Supreme Court’s clear instruction in Gaudin, in order to assess the materiality of the false statement that Mr. Sussmann is alleged to have made, this Court must ask what statement he is alleged to have made to the FBI; what decision the FBI was trying to make; and whether the false statement could have influenced that decision. Here, even accepting all the allegations in the Indictment as true—and the evidence would prove otherwise—the only decision the FBI was trying to make was the decision whether or not to commence an investigation into the allegations of suspicious internet data involving the Trump Organization and Russian Bank-1. Ample precedent—and the Special Counsel’s own allegations in this case—make clear that Mr. Sussmann’s purported false statement did not influence, and was not capable of influencing, that decision.

Predictably and reasonably, Durham’s response cited the precedent that leaves it up to juries to determine whether something is material or not.

In any event, the defendant’s arguments on the materiality of his statement are also premature. The Supreme Court in Gaudin held that materiality is an essential element of Section 1001 that must be resolved by a jury.

As I noted back in October, “Prosecutors will argue that materiality is a matter for the jury to decide.”

Prosecutors also noted what I did: a long list of precedents about materiality that Sussmann cited in his motion are all post-trial challenges to materiality, not pretrial motions to dismiss.

The defendant cites to multiple cases where the Supreme Court and Circuit Courts have held that the false statements and misrepresentations at issue were immaterial as a matter of law. See Def. Mot. at 7-10. But critically, all of those cases involved post-conviction appeals or motions to vacate the conviction after the Government presented its case at trial. Accordingly, none of these cases support the defendant’s requested relief here – that is, that the court dismiss the Indictment before trial because it fails to sufficiently allege that the defendant’s false statement is material. What the cases do show is that courts have routinely declined to usurp the jury’s role in making the determination on whether a false statement is material.

For those two reasons, Sussmann’s motion to dismiss is unlikely to succeed, and should instead be viewed as an opening bid to frame his defense and establish issues for appeal.

Those two arguments are all Durham really needed to respond to Sussmann’s motion to dismiss. Instead of leaving it with responsible lawyering, however, Durham instead launches into an illogical attempt to criminalize tip reporting.

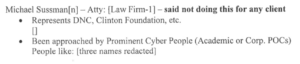

Take his attempt to dismiss Rodney Joffe’s real cybersecurity expertise. In the three months since he charged Sussmann, Durham belatedly (at Sussmann’s request) discovered how closely Joffe had worked with the FBI on other investigations. As Sussmann scoffed in an earlier filing, “The notion that the FBI would have been more skeptical of the information had it known of Tech Executive-1’s involvement is, in a word, preposterous.” Now that Durham has discovered the close ties between Joffe and the FBI, he claimed that that history of reliability was itself something the FBI needed to know.

Namely, as the defendant’s motion reveals (Def. Mot. at 18-19, fn. 8), Tech Executive-1 had a history of providing assistance to the FBI on cyber security matters, but decided in this instance to provide politically-charged allegations anonymously through the defendant and a law firm that was then-counsel to the Clinton Campaign. Given Tech Executive-1’s history of assistance to law enforcement, it would be material for the FBI to learn of the defendant’s lawyer-client relationship with Tech Executive-1 so that they could evaluate Tech Executive-1’s motivations. As an initial step, the FBI might have sought to interview Tech Executive-1. And that, in turn, might have revealed further information about Tech Executive-1’s coordination with individuals tied to the Clinton Campaign, his access to vast amounts of sensitive and/or proprietary internet data, and his tasking of cyber researchers working on a pending federal cybersecurity contract.

Durham’s claim that “learning” how much data Joffe had access to (which is something the FBI undoubtedly knew — it is surely the reason why FBI partnered with him, because the volume of data Neustar had made their observations more useful) would make them more skeptical of the DNS tip is nonsensical. In fact, elsewhere (in tracking all the YotaPhone requests in the US over a three year period), Durham treated it as presumptively reliable.

Plus, Durham made no mention here of one of a number of the other things he belatedly learned: that the September 2016 tip Sussmann shared with FBI General Counsel James Baker was not the only one Joffe had shared via Sussmann anonymously. He shared a tip anonymously during this same time period with DOJ IG. Durham has no way of knowing, either, whether those two were the only ones, but his revised theory of materiality depends on an anonymous tip like this one being unique.

Similarly, Durham struggled to explain (including by citing an inapt precedent) why the FBI would need to be told that Sussmann represented Hillary when, in notes of Baker’s retelling of the meeting, Bill Priestap wrote that Sussmann represented the DNC and Clinton Foundation.

As he did with Joffe, Durham tried to flip Sussmann’s expertise, arguing that the former prosecutor’s recognized qualification as a cybersecurity expert, something that would help him assess whether DNS data were anomalous or not, is precisely why the Perkins Coie lawyer needed to disclose he was working for Hillary.

In an effort to downplay the materiality of this false statement, the defendant asserts that the FBI General Counsel was aware that the defendant represented the DNC. See Def. Mot at 18. But the Government expects that evidence at trial will establish that the FBI General Counsel was aware that the defendant represented the DNC on cybersecurity matters arising from the Russian government’s hack of its emails, not that he provided political advice or was participating in the Clinton Campaign’s opposition research efforts. Indeed, the defendant held himself out to the public as an experienced national security and cybersecurity lawyer, not an election lawyer or political consultant. Accordingly, when the defendant disclaimed any client relationships at his meeting with the FBI General Counsel, this served to lull the General Counsel into the mistaken, yet highly material belief that the defendant lacked political motivations for his work.

There are many crazy assumptions built into this statement: that, had Sussmann identified Hillary as his client, it would have required him to reveal her motives as political rather than security-related to the FBI, breaching privilege; that reporting an anomaly potentially involving Trump after Trump had begged Russia to further hack Hillary would not be a sound decision from a cybersecurity standpoint; that researching the context of an anomaly, such as Alfa Bank’s ties to Putin, is not part of cybersecurity. Effectively, Durham has unilaterally decided that pursuing this anomaly was a political act, with no basis in law or fact.

Which is how Durham espoused the claim that the FBI, facing an unprecedented attack by Russia on American elections in 2016, might have delayed investigation of a part of it that might have implicated one of the contestants.

The defendant’s false statement to the FBI General Counsel was plainly material because it misled the General Counsel about, among other things, the critical fact that the defendant was disseminating highly explosive allegations about a then-Presidential candidate on behalf of two specific clients, one of which was the opposing Presidential campaign. The defendant’s efforts to mislead the FBI in this manner during the height of a Presidential election season plainly could have influenced the FBI’s decision-making in any number of ways. The defendant’s core argument to the contrary rests on the flawed premise that the FBI’s only relevant decision was binary in nature, i.e., whether or not to initiate an investigation. But defendant’s assertion in this regard conveniently ignores the factual and practical realities of how the FBI initiates and conducts investigations. For example, the Government expects that evidence at trial will prove that the FBI could have taken any number of steps prior to opening what it terms a “full investigation,” including, but not limited to, conducting an “assessment,” opening a “preliminary investigation,” delaying a decision until after the election, or declining to investigate the matter altogether.

[snip]

Moreover, the Department of Justice and the FBI maintain stringent guidelines on dealing with matters that bear on U.S. elections. Given the temporal proximity to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the FBI also might have taken any number of different steps in initiating, delaying, or declining the initiation of this matter had it known at the time that the defendant was providing information on behalf of the Clinton Campaign and a technology executive at a private company.

[snip]

And the evidence will show that it would have been all the more material here because the defendant was providing this information on behalf of the Clinton Campaign less than two months prior to a hotly contested U.S. presidential election. [my emphasis]

The first paragraph here is really telling, given Durham’s public complaint that the Crossfire Hurricane team should have opened the investigation as a preliminary investigation, not a full investigation (the investigation into Mike Flynn, specifically, wasn’t opened as a full investigation, but none of the techniques used would have otherwise been unavailable, not least because there was already a full investigation opened on Carter Page). This is an argument Durham may reprise in his report: That it was unreasonable for Hillary Clinton to ask the FBI to inquire into Trump’s campaign after he publicly asked a foreign country for help (even ignoring the tip from Australia).

Durham seems to think Hillary should have had no assistance from law enforcement when her opponent publicly asked Russia to hack her some more if people close to her found more reason to be concerned. He even mocked Sussmann as too powerful to choose to use anonymity.

[W]hile the defendant’s motion seeks to equate the defendant with a “jilted ex-wife [who] would think twice about reporting her ex-husband’s extensive gun-smuggling operation,” this comparison is absurd. Def. Mot. at 24

Far from finding himself in the vulnerable position of an ordinary person whose speech is likely to be chilled, the defendant – a sophisticated and well-connected lawyer – chose to bring politically-charged allegations to the FBI’s chief legal officer at the height of an election season.”

This also betrays pure insanity. The anomaly involving Trump could always have reflected disloyal insiders compromising the candidate, as could the YotaPhones potentially in use in Trump headquarters. In fact, Page did compromise Trump when he went to Russia in December 2016 and tell Russians there that he was representing Trump on matters pertaining to Ukraine, just as Mike Flynn did by selling his access to Trump to Turkey, just as Tom Barrack is accused of doing with the Emirates. The reason why Sussmann was providing this information less than two months before an election is because cybersecurity researchers had gone looking because there was an ongoing multi-faceted cybersecurity attack, one that continued right through the election, one that could have victimized Trump as well as Hillary.

Which brings me to the one point Sussmann made that Durham completely ignored. In his response, Durham’s response uses the word “purported” to describe the DNS allegations from Sussmann five times:

- The defendant provided the FBI General Counsel with purported data and “white papers” that allegedly demonstrated a covert communications channel between the Trump Organization and a Russia-based bank

- the purported data and white papers

- the purported DNS traffic that Tech Executive-1 and others had assembled

- the defendant provided data which he claimed reflected purportedly suspicious DNS lookups by these entities of internet protocol (“IP”) addresses affiliated with a Russian mobile phone provider (“Russian Phone Provider-1”)

- examine the origins of the purported data

What Durham did not do is ever address this point from Sussmann:

Indeed, the defense is aware of no case in which an individual has provided a tip to the government and has been charged with making any false statement other than providing a false tip. But that is exactly what has happened here.

In the fall of 2016, Michael Sussmann, a prominent national security lawyer, voluntarily met with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) to pass along information that raised national security concerns. He met with the FBI, in other words, to provide a tip. There is no allegation in the Indictment that the tip he provided was false. And there is no allegation that he believed that the tip he provided was false. Rather, Mr. Sussmann has been charged with making a false statement about an entirely ancillary matter—about who his client may have been when he met with the FBI—which is a fact that even the Special Counsel’s own Indictment fails to allege had any effect on the FBI’s decision to open an investigation.

[snip]

Again, nowhere in the Indictment is there an allegation that the information Mr. Sussmann provided was false. Nowhere is there an allegation that Mr. Sussmann knew—or should have known—that the information was false. And nowhere is there an allegation that the FBI would not have opened an investigation absent Mr. Sussmann’s purported false statement.

I could fund an entire Special Counsel investigation if I had $5 for every time in this prosecution Durham has used the word “purported.” For almost six months, his entire prosecution has been premised on this anomaly not being “real,” meaning unexplained traffic that might represent something serious.

And yet he has not charged that (though he seems to have bullied April Lorenzen, perhaps because he needs her to be something other than she was). Instead, he just keeps doing the work for which actual evidence is normally required by repeating the word “purported” over and over.

This motion to dismiss will likely fail, because juries get to decide what is material. But contrary to Durham’s claims, unless and until he can prove that Sussmann, Jofffe, and Lorenzen didn’t believe this was a real anomaly worth investigating given all the other attacks that, Sussmann especially, knew were ongoing, then he really will be prosecuting someone for reporting a valid national security concern.

“Durham instead launches into another illogical attempts to criminalize tip reporting.”

I’m curious if he’s hoping to lay the groundwork for more of this. I could easily imagine a lot of experts had reasons to pass on information possibly connected to Trump, Russians, or even domestic hackers in 2016 and for that matter 2020, but the grounds for investigation are probably even weaker than this unless he can manufacture some kind of pretext.

Sussman’s lawyers will make this the center of their opening statement, if this ever gets to trial.

I also envision a nice timeline on posterboard that will sit in front of the jury, so that they can absorb it. Maybe put a headline at the top like “Cybersecurity Concerns during the 2016 Election,” and then have a series of bullet points beneath it reflecting each item on that timeline, but each point covered up with paper. Then a series of witnesses is called, one to speak to each item on the timeline, at which point the paper covering that particular item is removed.

Sussman’s lawyers are obviously trying to get this thrown out well before it ever reaches an actual trial. But they are likely also beginning to craft their arguments and strategy at trial, and some of Durham’s nonsense has to have them drooling over the prospect of tearing Durham and his team apart.

Durham is down such a rabbit hole he may not realize that Russia was hacking Hillary’s analytics the same days when Sussmann met with the FBI.

Did Durham also prosecute the case against the Knave of Hearts? That would explain a lot about his approach to Sussmann.

The same as happened to Bill the Lizard in Alice in Wonderland:

https:// www. alice-in-wonderland.net/resources/chapters-script/the-nursery-alice/chapter-5/

Or doesn’t care. My baseline assumption is that he’s a partisan hack who doesn’t care a whit about what might befall a Democrat.

Did they ever investigate the hacking of the RNC computers? Or was that all just in case the former guy lost?

Won’t anyone rid me of this meddlesome priest?

What does this fool take us for?

Re #1: Apparently not.

Re #2: Something north of $100,000 a year. Probably well north.

HA! Add in staff, consultation grift, admin costs, general smarmy bs; gotta be well north of 7 figures.

There is also the opportunity cost of DoJ resources being diverted away to Durham, right during the time when COVID, and Jan6, would be reducing, and taking up, human resources. These are probably the days of money for jam for many federal-crime-ing types in the USA. “Hey Rex, remember how easy it was back in 21? Not a G-man to be found, even if you went looking. Not that we ever did mind you. Ha ha”.

I missed the significance of that Brogan reference. In Brogan v. United States, Brogan lied about his guilt of the underlying crime. The key to all of this is that Durham desperately needs Joffe, et. al., to have faked their DNS data for any of Durham’s gratuitous bullshit to make sense. In the process, he’s implying that making an FBI tip while representing a political campaign ought to be illegal.

But also that it was asked by prosecutors who knew the person was guilty. It dodges on Sussmann’s point again: All the FBI was considering was whether to open an investigation.

A dumb question: In the indictment, it is claimed that Sussman “stated falsely” that he was not there on behalf of anyone; Sussman denies this claim. What evidentiary basis is there to make this allegation–is there a recording, transcript, or notes of Sussman’s talk with the FBI General Counsel in which the GC asks Sussman who he’s working for, to which he responds “nobody”? Is it based on the GC’s recollection? The belief that asking such questions of tipsters is SOP for FBI interrogations (most of which aren’t carried out, I imagine, by the General Counsel) and that he MUST have been asked?

It seems that without either documentary evidence or a witness to the false statement in question, this is going to be a real short trip.

There were no tapes. The entire issue rests on the recollections of one person, James Baker, whose memory of the event is vague as to whether Sussman was asked directly, and/or what is answer might have been. There were some notes taken, but they’re based on Baker’s recollection after the fact, and don’t go into detail about the matter, which wasn’t germane to Sussman’s report, and obviously not considered important at the time.

In his entire case against Sussman, Durham has been playing to an audience. That audience believes that the crime here is that Sussman did indeed do legal work for the Clinton campaign, and thus is guilty of a grievous crime. It’s the 2022 version of “lock her up!”

I just stumbled on interesting relationship. Durham’s Special Counsel prosecutor Anthony Scarpelli, the lead prosecutor of the Kevin Clinesmith prosecution, is running Jan . 6 case against Brian Sitnick’s attackers Khater and Tanios.

Is this just normal DC USAO business for Scarpelli, or is this a sideways in for Durham into Jan. 6?

Scarpelli’s involved with Durham primarily bc of the Clinesmith prosecution. At that point Durham needed a DC US Attorney.

Got it. Thank you for confirming. After an initial gut clench at the overlap in cases, I resolved it’s likely normal DC business and not anything overtly conniving.

I think the chances of the motion being granted are greater than as estimated by Ms. Wheeler.

Although the prosecutors response uses the word “evidence” frequently, the prosecution doesn’t seem to have any evidence on the issue at hand. It doesn’t claim to have an FBI agent saying they wasted resources on an unnecessary investigation or that they delayed a meritorious investigation. As Ms. Weeler notes, the word purported is used to cast doubt on the technical evidence, but there is no testimony that the information was false or that the FBI was misled by the technical evidence. It looks like the Sussman evidence was added to cyber security files as another guide. The must be some evidence that the person who received the statements was misled. Arguments that they might have misled are not going to be sufficient.

Juries determine materiality, But there has to be someone saying they were misled about something more serious than weather the coffee maker was working,

I think the prosecution will be dismissed, But if not the court is likely to create some very stiff requirements on the type of evidence that can be submitted.

The court may also rule that the technical evidence provided by the defendant was accurate and verifiable and that cannot be disputed.

Let’s split the baby. Dismissal without prejudice, and/or an opportunity for the government to amend the pleadings to include some factual allegations that aren’t “purported” if they want to move to the next phase, and/or denial of the motion to dismiss but a warning to the government that with the current state of the case, a summary judgment motion from the defense might well be granted, if the allegations cannot be substantiated with actual witnesses.

Correct.

An excellent breakdown of Durham’s “purported” prosecution. Many thanks, as always!

I’m still trying to work out on how many times a prosecutor gets to prosecute another prosecutor. Tell you what, I’ll get back to you on that.

This a not a close call. The MTD has literally no chance. Give me a break!

Lol, unless you are the assigned District Judge, and have already made up your mind, such proclamations often prove to be problematic.

“This motion to dismiss will likely fail, because juries get to decide what is material.”

Doesn’t the prosecution need to have someone who is willing to testify that Sussman’s purported lie was material (or similar written evidence) before they can drag him into a courtroom? After all, isn’t Mr Durham supposed to have a reasonable expectation of obtaining a conviction before bringing a case? He can’t argue materiality in his opening and closing statements without presenting evidence, can he? Yes, the jury gets to assess the strength of the evidence for materiality, but shouldn’t a judge be able to dismiss if the prosecutor hasn’t disclosed how he intends to prove materiality?

Is the prosecution required to prove materiality beyond a reasonable doubt, or can they prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Sussman lied and get away with a lesser standard when asserting materiality?

James Baker likely could speak definitively about materiality, but he might be easy to discredit with questions about how he feels about the FBI having been dragged through the mud by Trump, Durham and their allies. With competing uninvolved experts testifying and cancelling each other, maybe Sussman could be convicted.

Good grief, you have no clue what you are talking about. Give it a rest.

If you assume they are not rhetorical, these all seem like reasonable questions to me. They’re not questions which show great knowledge of the law, but they’re not unreasonable from a layman. So I’ll rephrase Franktoo’s questions to the essential, and maybe you can answer me:

If you were defending Sussman’s case, how would you explain to a Federal judge that the prosecution’s case is a bloated cloud of crap which reeks of politics and bovine excrement? And what would be the consequence for your client if you did this in whatever form “the right way to say it” would take?

Dr Marcy, this statement of yours gives me chills:

“Effectively, Durham has unilaterally decided that pursuing this anomaly was a political act, with no basis in law or fact.”

I’m not sure Durham so much “decided” this as I believe he was tasked to do this. Find a way to place constraints on investigating illegal hacking activity (foreign or domestic in source) that is ongoing and targeting, for purposes of influence, an American general election, by painting any and all reportage of such as politically motivated.

American political environment has only 2 major bodies and conservative media for the past 3.5 decades has done a very thorough job of politicizing just about every damn aspect of American society to shoe horn all policy positions into one shoe box or the other. Should Durham succeed here, it could become next to impossible, in the future, to expose any criminal activity occurring within the orbit of a political campaign because the assumption then becomes that exposing such activity will always be politically motivated.

And that would be some really dangerous bullshit right there.

Sessions, Barr, and the Federalist Society have been working to undermine the rule of, and institutions of law for a long time. Chaos and insider-dealing are the means to the end where their allies get to choose winners and losers. So, like Russia, they aim to have concentrated decision making on who gets to say what, and when.

Durham seems to be demanding that Sussman violate ethical obligations, perhaps the sort of obligations compulsory to the profession.

It shouldn’t matter what Sussman’s motivations were; ultimately the FBI had the responsibility and resources to determine the credibility of information, and if the tip had turned up false, whether there were corrupt motivations in reporting that tip.

If one of my kids tells me that their sibling, in a sing-song manner, is playing with a lighter by the drapes, and tonight they were promised iced cream for dessert, whether or not they both get dessert isn’t going to matter if the house catches fire. If there was no dessert, if their dad planned the dessert unbeknownst to me, still doesn’t matter if drapes are in flames. It’s my job as a parent to ensure the home is safe and free of fire, and then as to whether anyone’s actions merit punishment, before handing it out.

Likewise, I’m sure the FBI could and would file charges against Sussman if what he reported was outright false. The duty would also fall to the FBI to address the problem if found, and to do so in a way that avoids tainting an ongoing election unnecessarily.

[Welcome back to emptywheel. Please use a more differentiated username when you comment next as we have several community members named “Erin.” Blank lines inserted into your comment between paragraphs to improve readability. Thanks. /~Rayne]

Paragraph breaks are your friend. And that is not exactly how the FBI works.

They used returns and depending on the device and browser the returns may not have left a blank line between grafs.

Sorry if I missed it, but did Durham explicitly respond to Sussman and say that the FBI would have reacted differently if it knew Sussman was acting on behalf of the Clinton Campaign? It seems like he’s throwing same in everyone’s face with a lot of extraneous information.

Keep in mind:

Sussmann’s clients were not a secret within DC; including with the FBI. That he had the Clinton Campaign as a client was not something that was concealed. He didn’t mention it explicitly, but he was there on behalf of another client (Joffe); the suggestion that he was secretly advancing the interests of Hillary instead of (or in addition to) those of Joffe is essentially what the accusation is. (Joffe has not complained, to my knowledge, that Sussmann was not representing him faithfully).

But there are no facts on the record so far as to support it. This is not a civil case, where you can file a complaint full of accusations “on information and belief”, there’s a lot of motion practice and discovery, including the opportunity for either side to seek summary judgment, and the trial is the last phase after the judge has determined a) there is a case to be answered, b) neither side should get to win because no reasonable interpretation of the facts/evidence doesn’t lead to a mandated outcome, and c) the case needs to be now decided by triers of facts, to determine whose set of evidence is more persuasive.

The prosecutor should already have a well-formed case, which should have already been shared with the defense. Minor defects in the case may be correctable, but if Durham doesn’t have witnesses or evidence available that prove the allegations in the indictment, at some point the judge should throw this out. Perhaps on summary judgment rather than a motion to dismiss, but Sussmann’s lawyers should know exactly the strength of the government’s case.

Exactly. Durham’s case, as far as I can tell, doesn’t seem to exist. He’s putting words together to make what sounds like a reasonable legal argument, but ultimately there’s lots of verbiage without an actual crime. It’s such an obvious case of “I’ve got nothing to say, but I’m going to say it anyway,” that if I were on the jury I’d be inclined to find Durham guilty.*

* Before Bmaz starts roaring like an animal in a cage, I do understand that a jury can’t find the prosecutor guilty, which in this case is a damn shame!

Durham’s entire case is essentially in one clause of the indictment (clause 27a): “SUSSMAN stated falsely that he was not acting on behalf of any client, which led the FBI General Counsel to believe that SUSSMAN was conveying the allegations as a good citizen and not as an advocate for any client”, along with the claim that Sussman billed the Clinton Campaign for his time with the FBI General Counsel, and various claims of materiality.

Sussman’s motion to dismiss contains an explicit denial of the false statement that was alleged. (This denial is not relevant to a motion to dismiss, as it is a factual element of the prosecution’s case which must be considered true when a MTD is considered). He also notes that nowhere in the indictment is it plead that the FBI relied on Sussman’s statement thinking he was a “good citizen” and would have ignored it otherwise had they thought he was a political operative.

This point is probably the biggest weakness of the prosecution’s case–but again, it’s a factual matter not ripe for a motion to dismiss, which is why we get all sorts of legal argument that the motives of a tipster can’t be relevant, only the substance of the tip… which isn’t a bad argument, actually, but it’s not one the judge might be inclined to bite on.

So the “lie” is real because it’s about something “not real”? Is Dunham the Cretan?

Of course, Sussmann’s lawyers know that they have no chance of prevailing on their motion to dismiss the indictment. Courts simply don’t decide materiality without the benefit of a full evidentiary record. So why file it? The usual answer lawyers give when filing something weak: The client insisted on it and is willing to pay for it. There’s a more cynical answer (which has to do with politics) that I’d rather not dignify, and I’d surmise isn’t the reason the motion was filed.

It seems to me that reasonable people can agree that what the Clinton campaign and its lawyers tried to pull in linking Trump to Russia was, to use an overplayed word, crooked. Whether criminality was involved is another thing. However, I think Sussmann’s lawyers would be remiss if they weren’t asking him seriously to consider cooperating. People like Sussmann don’t do well even during relatively short stints in federal prison.

A couple of observations in response to your commentary.

First, the “Russia are you listening” statement has nothing to do with the case. Whether that idiotic “joke” triggered the hacking of Podesta’s emails is the kind of unmoored speculation that creates heat, not light. Yes, I know you readers love it, but surely that isn’t the test.

Second, this indictment alleges far more than “tip reporting.” Obviously, it could all be hot air and unprovable at trial, but to seek a dismissal by analogizing this to tip reporting simply doesn’t pass the straight-face test, and is the kind of argument that could undermine the credibility of Sussmann and his team in the eyes of the judge. Yes, those kinds of atmospherics count.

Third, the Priestap notes are highly material to Sussmann’s case, and not in a way that favors the defense. On their face, they support the materiality of Sussmann’s alleged statements.

Finally, so far, the publicly available evidence suggests that no one genuinely thought that the “evidence” pertained to a valid national security concern. And although that isn’t an element of the case, I suspect we’ll get an earful on this issue, one way or another, at trial. It remains to be seen whether Sussmann will present expert testimony to support this proposition and how such testimony will fare in the cold light of the courtroom.

It does not appear you understand anything about lawyering or courts. Because you always protect the record. But you would know that if you knew anything.

I understand just enough to have had a long, successful career handling complex criminal and civil cases, apparently. That should do here.

I might add that floating dubious theories on a motion to dismiss doesn’t protect anything.

Lol, sure.

Oh, I am. :)

Lol! Sussmann’s counsel Latham is apparently also a client of Durham’s Witness-1, James Baker.