John Durham’s Cut-and-Paste Failures — and Other Indices of Unreliability

It would be unfortunate if the press corps responded to evidence that significant numbers of reporters had uncritically magnified the Steele dossier by uncritically magnifying other demonstrably unreliable documents. Yet that is what has happened in response to the Igor Danchenko indictment, today in fairly notable form in a Bill Grueskin op-ed in the NYT.

Grueskin calls for more reporting

To be clear, the conclusion of Grueskin’s op-ed (like the dossier’s conclusion that members of the Trump campaign were in contact with key players in the Russian election operation and the DOJ IG Report’s conclusion that the Carter Page FISA applications were badly flawed) is absolutely correct: news organizations should come clean about past erroneous reporting on the dossier and, when in doubt, should do more reporting.

[N]ews organizations that uncritically amplified the Steele dossier ought to come to terms with their records, sooner or later. This is hard, but it’s not unprecedented. When The Miami Herald broke the news in 1987 that the Democratic presidential candidate Gary Hart was seeing a woman other than his wife, the paper followed that scoop with a 7,000-plus-word examination of its investigation, which showed significant flaws in how the paper surveilled its target.

[snip]

Newsrooms that can muster an independent, thorough examination of how they handled the Steele dossier story will do their audience, and themselves, a big favor. They can also scrutinize whether, by focusing so heavily on the dossier, they helped distract public attention from Mr. Trump’s actual misconduct. Addressing the shortcomings over the dossier doesn’t mean ignoring the corruption and democracy-shattering conduct that the Trump administration pushed for four years. But it would mean coming to terms with our conduct and whatever collateral damage these errors have caused to our reputation.

In the meantime, journalists could follow the advice I once got from Paul Steiger, who was the managing editor of The Journal when I was editing articles for the front page. Several of us went to his office one day, eager to publish a big scoop that he believed wasn’t rock solid. Mr. Steiger told us to do more reporting — and when we told him that we’d heard competitors’ footsteps, he responded, “Well, there are worse things in this world than getting beaten on a story.”

As someone who first raised concerns about the provenance of the dossier on January 11, 2017, caught a lot of grief for a long piece calling out real errors in it on September 6, 2017, and started raising concerns about disinformation in the dossier on January 29, 2018, before that became the consensus among Republicans in Congress, there are still key details about the dossier that demand more attention. But they’re not the ones that are getting the most attention.

Oleg Deripaska’s role in the dossier remains largely unreported

By far the most important unreported detail about the dossier, in my opinion, is the brutal double game Oleg Deripaska was playing with Christopher Steele and Paul Manafort. Consider the following details, all readily available in the public record:

- In March 2016, per Igor Danchenko’s January 2017 interview report, Steele tasked him to collect information on Paul Manafort. Danchenko said he did not know the client for that project, but communications between Steele and DOJ’s Organized Crime expert Bruce Ohr FOIAed by Judicial Watch as well as documents leaked to Byron York show that Steele was doing work on behalf of Deripaska’s lawyers at the time (note that York mistakes a reference to Deripaska as “our favourite business tycoon” for Donald Trump).

- By early July 2016 (so after just the first dossier report), according to a footnote from the DOJ IG Report declassified for Chuck Grassley and Ron Johnson, “a [person affiliated] to Russian Oligarch 1 [[Deripaska]] was [possibly aware] of Steele’s election investigation.”

- On July 30, 2016 (so after a Deripaska associate may have learned of the dossier), according the DOJ IG Report, “Steele told Ohr that [Oleg Deripaska]‘s attorney was gathering evidence that Paul Manafort stole money from [Deripaska].”

- On August 2, 2016, according to the Mueller Report, partly in an attempt to “get whole” on the money Deripaska accused Manafort of stealing, Manafort met with Deripaska deputy Konstantin Kilimnik and discussed, in addition to how to get that debt forgiven, “the state of the Trump Campaign and Manafort’s plan to win the election,” including, “discussion of ‘battleground’ states, which Manafort identified as Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Minnesota,” and what Manafort described as a “backdoor” way for Russia to control eastern Ukraine.

Even as the investigator employed by Deripaska’s lawyers, Christopher Steele, was sharing Deripaska-sourced claims of Manafort’s corruption with DOJ, Deripaska was using Manafort’s legal and financial vulnerability arising from that corruption to learn how Trump planned to win the election and to recruit Manafort’s help in carving up Ukraine. Deripaska was working a brutal double game, using Steele as cover with DOJ and FBI even as he exploited Manafort’s vulnerability — which had been enhanced by Steele — to make demands on Manafort. That’s the core scandal of Steele’s actions in 2016. Yet reporters who entirely missed this story are being treated as experts on the problems with the dossier.

So I find Grueskin’s conclusion, there’s still reporting to be done, sound.

It’s just how gets there, by replicating the very problems he critiques, that I object to. In a piece complaining that journalists uncritically amplified the dossier, Grueskin uncritically relies on the DOJ IG Report on Carter Page and Durham’s indictment of Igor Danchenko.

The dossier’s credibility suffered a grievous blow in December 2019, when an investigation by the Department of Justice’s inspector general found that F.B.I. investigations “raised doubts about the reliability of some of Steele’s reports.” The F.B.I. “also assessed the possibility that Russia was funneling disinformation to Steele,” the report said, adding that “certain allegations were inaccurate or inconsistent with information gathered” by investigators.

Then, this month, a primary source of Mr. Steele’s was arrested and charged with lying to the F.B.I. about how he obtained information that appeared in the dossier. Prosecutors say that the source, Igor Danchenko, did not, as The Wall Street Journal first reported, get his information from a self-proclaimed real estate partner of Mr. Trump’s. That prompted a statement promising further examination from The Journal and something far more significant from The Washington Post’s executive editor, Sally Buzbee. She took a step that is almost unheard-of: removing large chunks of erroneous articles from 2017 and 2019, as well as an offending video.

Neither should be treated uncritically, particularly with regards to the dossier.

Indices of unreliability in the DOJ IG Report

The DOJ IG Report revealed its unreliability itself, issuing two sets of corrections in the days after its release. Two of those corrections pertained to the dossier. The first correction admitted that the Report had initially miscited Igor Danchenko’s interview report regarding a report Danchenko sourced to Sergei Millian, the key report at issue in the Danchenko indictment.

On pages xi, 242, 368, and 370, we changed the phrase “had no discussion” to “did not recall any discussion or mention.” On page 242, we also changed the phrase “made no mention at all of” to “did not recall any discussion or mention of.” On page 370, we also changed the word “assertion” to “statement,” and the words “and Person 1 had no discussion at all regarding WikiLeaks directly contradicted” to “did not recall any discussion or mention of WikiLeaks during the telephone call was inconsistent with.” In all instances, this phrase appears in connection with statements that Steele’s Primary Sub-source made to the FBI during a January 2017 interview about information he provided to Steele that appeared in Steele’s election reports. The corrected information appearing in this updated report reflects the accurate characterization of the Primary Sub-source’s account to the FBI that previously appeared, and still appears, on page 191, stating that “[the Primary SubSource] did not recall any discussion or mention of Wiki[L]eaks.”

Effectively, DOJ IG realized only after it published that it had not cut-and-pasted from Danchenko’s interview report accurately.

The second correction admitted that, in its original release, the IG Report had complained that the FBI had not integrated information that it learned from Danchenko starting on January 24, 2017 in a FISA reauthorization approved on January 12, 2017, a temporal impossibility.

On page 413, we changed the word, “three” to “second and third.” The corrected information appearing in this updated report reflects the accurate description of the Carter Page FISA applications that did not contain the information the FBI obtained from Steele’s Primary Sub-source in January 2017 that raised significant questions about the reliability of the Steele reporting. This information previously appeared, and still appears, accurately on pages xi, xiii, 368, and 372.

These corrections show that DOJ IG got all the way through its initial release without noticing sloppiness of the sort it found inexcusable from the FBI.

But the far more important change DOJ IG made after first publication — one that still has not been fully corrected — is that all the way through its initial release, IG investigators had misdescribed what crimes the FBI team was investigating, conflating FARA and 18 U.S.C. § 951. The error was absolutely critical, because the investigation into Carter Page was initially opened because he was willingly sharing non-public economic information with people he knew to be Russian intelligence officers. Page would have already passed certain First Amendment review required for a FARA case before the case was picked up by the Crossfire Hurricane team. The correction should have, but did not, lead to wholesale reconsideration of the First Amendment discussion in the IG Report. Relatedly, the IG Report still includes an uncorrected miscitation to a Senate Report on the statute in question, to a passage that explained that an American could be targeted for First Amendment activities if he was — as Carter Page had been prior to 2016 — “acting under the direction of an intelligence service of a foreign power.”

Incidentally, John Durham replicated this error in the first document formally filed as part of his investigation, the Kevin Clinesmith information, revealing that 15 months into his investigation into Crossfire Hurricane, he didn’t even know what crimes Crossfire Hurricane had been investigating.

The corrections the IG Report made are not the only evidence that it is not entirely reliable. The report included a number of omissions, just like the Carter Page FISA applications did. For the purposes of this post, the most important are that it made no mention of the contacts Christopher Steele and Bruce Ohr had before July 30 during 2016 — contacts that focused on Deripaska; it left out one topic of their discussion on July 30, Russian doping; and it misrepresented Ohr’s key role in providing derogatory information about Steele to the FBI that they used to vet the dossier. In other words, DOJ IG misrepresented some of the relevance of Oleg Deripaska to the Russian election operation, which may be why that remains an unreported aspect of Steele’s role in 2016.

Indices of unreliability in Durham’s Danchenko indictment

Grueskin’s — and much of the media’s — uncritical reliance on the Danchenko indictment raises still further problems. Of course, all DOJ press releases on indictments, including the one announcing Danchenko’s charges, emphasize that, “Charges contained in an indictment are only allegations.” And as reporters learn early on, prosecutors (more often state and local prosecutors, but Federal prosecutors are not immune) often make allegations that aren’t backed by the facts.

We won’t be able to fully assess the allegations that Durham has made against Danchenko until Danchenko either pleads guilty or goes to trial.

But there are three reasons not to treat this indictment as credible without further proof:

- It fails to represent transcripts faithfully

- It relies on Sergei Millian’s Twitter account as evidence for a key allegation

- A number of its most newsworthy allegations are not actually charged

Durham’s misrepresentation of Danchenko’s alleged lies

Durham’s indictment of Michael Sussmann, unusually for a false statements indictment, does not quote the lie that Sussmann is alleged to have told.

By contrast, Durham does provide transcripts for some, but not all, of the lies he charges in the Danchenko indictment, though in the actual charges, he usually relies on a few words rather than the full statement of Danchenko’s alleged lie.

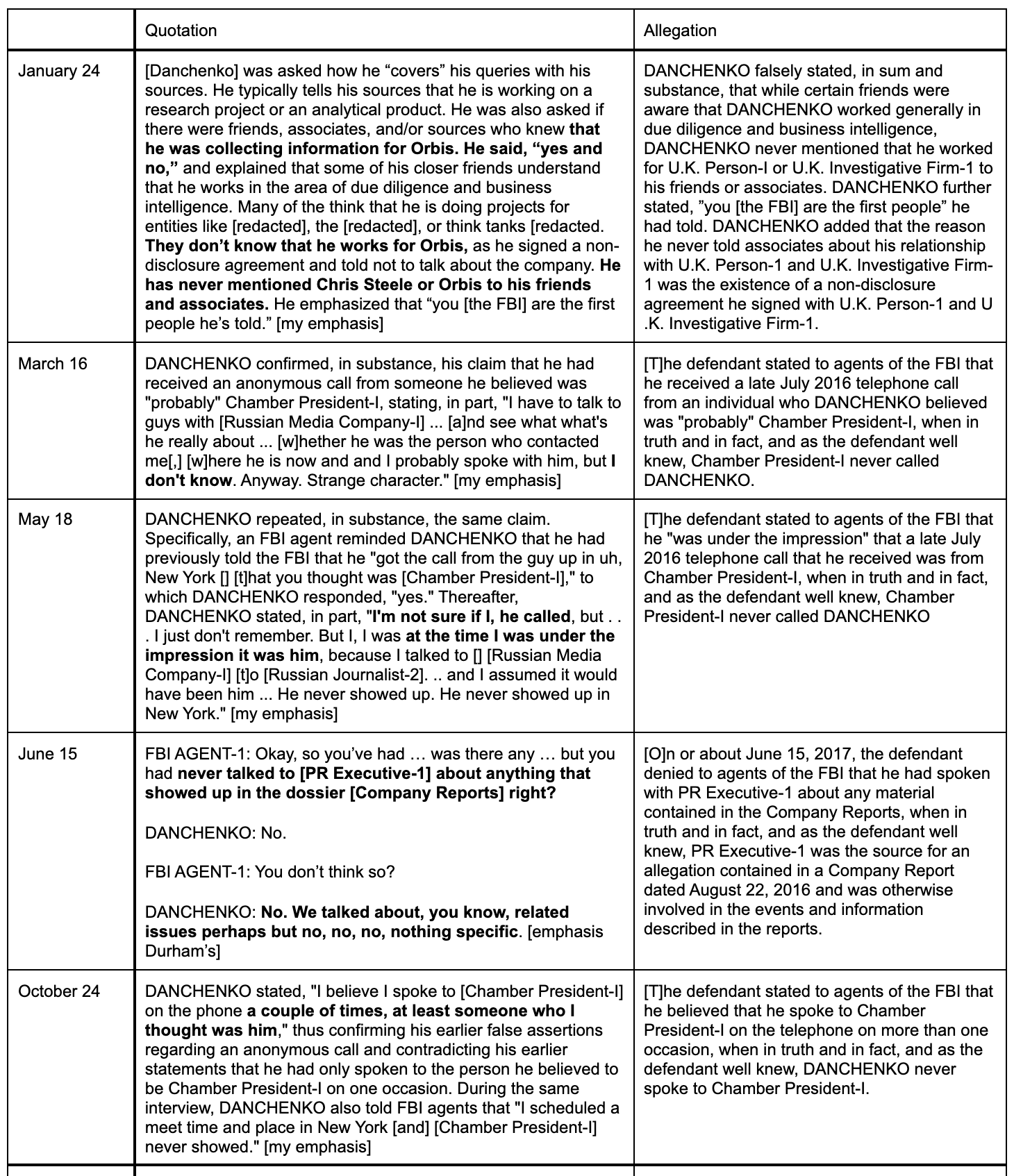

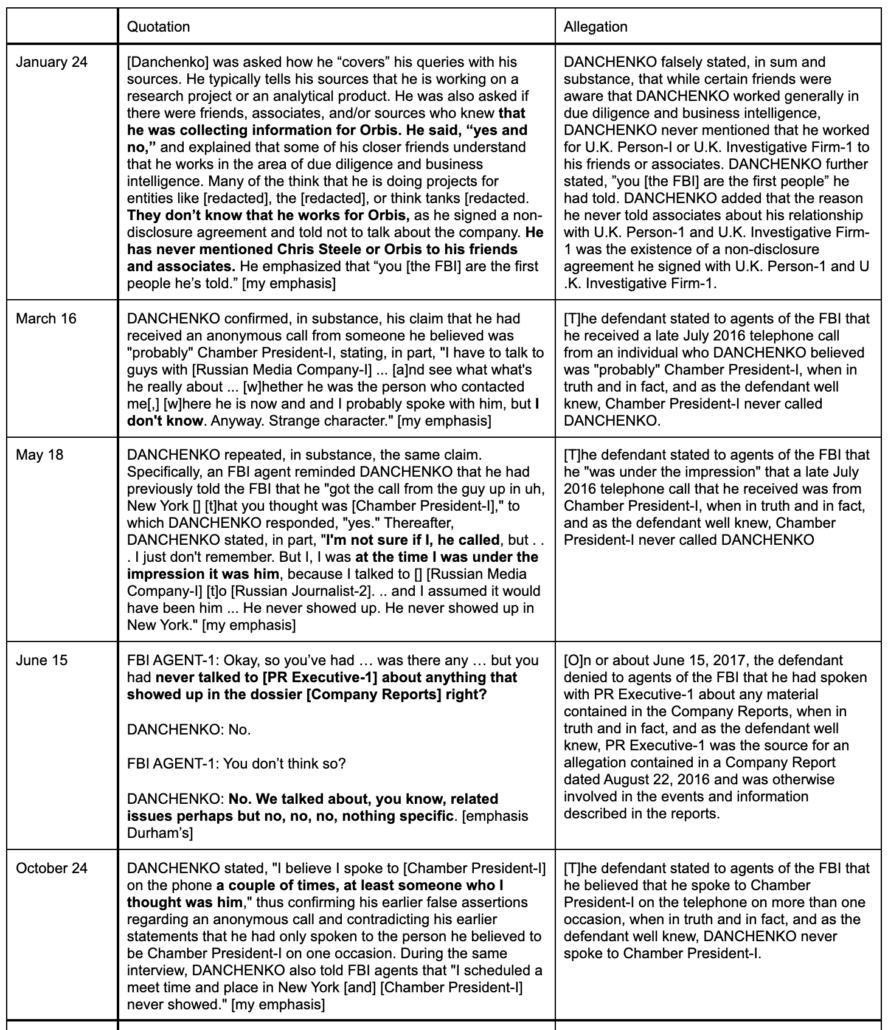

That means we can test Durham’s reliability by comparing the actual transcripts with how Durham describes the alleged lies in his charges. (Durham does not include the interview report for the uncharged January 24 allegation below, but it is publicly available, and Durham provided neither a transcript nor summary of Danchenko’s language relating to a November 16, 2017 interview.)

In each case, Durham’s charged lies leave out key caveats or context that appear in the actual transcripts.

In his (uncharged) allegation that Danchenko falsely claimed, on January 24, 2017, that he hadn’t told any of his associates he “worked for Chris Steele or Orbis,” Durham didn’t explain that this was a question specifically about whether Danchenko’s friends knew he collected intelligence for Orbis, not whether he knew Steele at all, nor does he reveal that Danchenko responded to the question, “yes and no.”

In the Millian-related charge pertaining to a recorded March 16, 2017 interview, Durham claimed that Danchenko “well knew” that Millian had never called him, omitting that Danchenko actually stated that “I don’t know” whether he really spoke to Millian.

In the Millian-related charge pertaining to a recorded May 18, 2017 interview, Durham omitted several key details, including that Danchenko was describing what he believed, “at the time,” (in 2016) and that he was “not sure” if Millian really called.

In the single charge relating to Charles Dolan, Durham omitted that the first question the FBI Agent asked Danchenko about Dolan on June 15, 2017 appears to pertain to whether Dolan was a source for Steele, not whether he was a source for Danchenko. It also omits Danchenko’s caveat that he and Dolan had “talked about … related issues” to the dossier, though not anything “specific,” which is not a categorical denial that he spoke to Dolan about “any material contained” in the dossier.

In a Millian-related charge pertaining to an October 24 interview (Durham doesn’t say whether this was recorded), Durham omits that Danchenko caveated his answer by saying that the caller “was someone who I thought” — again reflecting his belief in 2016, not in 2017 — was Millian.

These omissions don’t doom Durham’s case; they don’t mean Danchenko didn’t lie. But they do show that Durham left out key language and context in the language charging these as lies.

Durham may well prove his case (the Dolan charge is, in my opinion, the strongest one), but his failures in cutting and pasting the language from the transcripts accurately suggests he cannot be relied on uncritically as a source about what really happened.

Sergei Millian’s Twitter feed is no more reliable in an indictment than outside it

All the more so given that Durham, remarkably, relies on Sergei Millian’s Twitter feed as one of the few pieces of proof that the call Danchenko believed to have come from Millian did not take place.

Chamber President-I has claimed in public statements and on social media that he never responded to DANCHEKNO’s [sic] emails, and that he and DANCHENKO never met or communicated.

Durham presents just two other pieces of evidence that the call didn’t take place, both of which post-date the first dossier report purportedly based on the call (meaning neither is proof, at all, that Danchenko didn’t believe Millian was the caller at the time he submitted the report to Steele). And he leaves out a communication Danchenko had that may corroborate the call (or at least Danchenko’s contemporaneous belief it did).

Unless there are FBI interviews with Millian that Durham is obscuring (he’s not obscuring Dolan’s interviews), it is fairly unbelievable that Durham presented this Twitter allegation to a grand jury, because it is not remotely admissible for the facts claimed at trial. Durham appears to be treating Millian — whom FBI also had a counterintelligence investigation on in 2016 — as a fact witness without requiring Millian undergo the same kind of FBI exposure that Danchenko was willing to.

That, itself, is newsworthy, because it reflects poorly on the seriousness of Durham’s case.

Journalists treating Durham’s Twitter-based allegations as credible should ask themselves why they hadn’t, themselves, treated the very same Millian assertions as credible four years earlier, before this indictment. The answer is obvious: because Twitter feeds aren’t normally sufficient proof, for prosecutors or journalists, of any fact beyond that a statement was made. Yet journalists are now taking the appearance of this Twitter claim within an indictment as proof that it is true.

Durham’s uncharged allegations

The last reason why Durham’s Danchenko indictment should be treated with skepticism is more technical but one that has been the key source of bad reporting on it.

Durham charged five false statements, a single charge relating to Charles Dolan, and four counts charging the same lie about a Sergei Millian call allegedly made in four different FBI interviews (one instance of this claimed lie, made in January 2017, is not charged).

Durham also made another allegation that he didn’t charge — the alleged lie on January 24 regarding whether Danchenko told others he was collecting intelligence for Steele.

And Durham presented, as materiality arguments, three dossier reports that Durham doesn’t allege Dolan was the direct source for, but instead, describes that he, “was otherwise involved in the events and information described in the reports.” Here’s how Durham justifies including the allegations about the pee tape as a materiality claim.

Based on the foregoing, DANCHENKO’s lies to the FBI denying that he had communicated with PR Executive-I regarding information in the Company Reports were highly material. Had DANCHENKO accurately disclosed to FBI agents that PR Executive-I was a source for specific information in the aforementioned Company Reports regarding Campaign Manager-1 ‘s departure from the Trump campaign, see Paragraphs 45-57, supra, the FBI might have taken further investigative steps to, among other things, interview PR Executive-I about (i) the June 2016 Planning Trip, (ii) whether PR Executive-I spoke with DANCHENKO about Trump’s stay and alleged activity in the Presidential Suite of the Moscow Hotel, and (iii) PR Executive-1 ‘s interactions with General Manager-I and other Moscow Hotel staff. In sum, given that PR Executive-I was present at places and events where DANCHENKO collected information for the Company Reports, DANCHENKO’s subsequent lie about PR Executive-1 ‘s connection to the Company Reports was highly material to the FBI’ s investigation of these matters.

Durham doesn’t claim that Dolan was the source for the pee tape (though a number of media outlets have claimed he did, even while complaining about bad reporting on the dossier). A likely — and damning — potential explanation is that Danchenko learned from Dolan the name of Ritz Hotel staffers and then used their names, without interviewing them, to make the pee tape rumor Danchenko sourced to a Russian friend of his look more credible. But there’s no hint that Dolan willfully participated in the manufacture of the pee tape report (indeed, the indictment provides several reasons to believe he did not). Durham actually doesn’t even claim that he knows what Dolan’s role was in the pee tape, other than inviting Danchenko to the Ritz for lunch. For example, he may not be able to rule out that, after getting the names of Ritz staffers from Dolan, Danchenko interviewed them. Nor does Durham claim to know what happened with the other two Dolan-related allegations he includes as materiality arguments.

But based off a long narrative presented as a materiality argument, not a separate charged crime (it’s all part of Danchenko’s alleged denial of discussing anything specific that appeared in the dossier), multiple reporters have claimed that there are charges, plural, tied to Dolan and that a Clinton associate had a role in manufacturing the pee tape claim. Neither claim is supported by the Danchenko indictment, but the misimpression may be what Durham was hoping to accomplish by including it.

Durham did something similar in the Sussmann indictment, and as lawyers for both Sussmann and Danchenko have noted, the move impermissibly presents Rule 404(b) information in an indictment, information about motive or other bad acts that might be presented at trial with prior approval from the judge to help prove the case. By doing it, Durham skirts a DOJ rule (the one Jim Comey broke in 2016) against making public allegations that DOJ is not prepared to prove beyond a reasonable doubt.

Effectively, these materiality claims are the equivalent of journalistic scoops that aren’t rock solid that — Paul Steiger told Grueskin years ago — require more investigation before charging or reporting. These materiality claims are no more substantive than the reports in the Steele dossier.

And yet some in the press are treating them as such, most often by treating them (or at least the pee tape one) as a separate charge, and claiming that Durham has alleged something about the pee tape that he has not.

Durham’s Danchenko indictment may one day prove — like the dossier, the DOJ IG Report, and Grueskin’s op-ed — generally right, even if some of the facts in it are wrong.

But it hasn’t yet proven any more reliable, with regards to specific facts, than the dossier itself. And there are several signs that it is not reliable.

It would be a mistake to respond to the bad reporting on the dossier by replicating the same bad habits with the Danchenko indictment.

Danchenko posts

The Igor Danchenko Indictment: Structure

John Durham May Have Made Igor Danchenko “Aggrieved” Under FISA

“Yes and No:” John Durham Confuses Networking with Intelligence Collection

Source 6A: John Durham’s Twitter Charges

John Durham: Destroying the Purported Victims to Save Them

John Durham’s Cut-and-Paste Failures — and Other Indices of Unreliability

Durham seems to be riding his reputation for oversight gained from the Whitey Bulger case. His investigation of Jose Rodriguez and the destruction of CIA interrogation tapes ended with a whimper, as did his dive into the “enhanced interrogation techniques” of the Bush regime.

If I didn’t know better, I’d almost think that with Durham in charge, an investigation into government actions that reflect poorly on Democrats results in charges and trials, while investigations that might make Republicans look bad get pushed to the side.

Honestly, reading this post (and many of those on which this one is built) makes me seriously ask “idiot or crook?”

CIA investigation whimpered by design:

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/statement-attorney-general-eric-holder-closure-investigation-interrogation-certain-detainees

From Holder’s mandate to Durham: “Attorney General Holder made clear at that time, that the Department would not prosecute anyone who acted in good faith and within the scope of the legal guidance given by the Office of Legal Counsel regarding the interrogation of detainees.”

Anyone who tortured anyone under Bush’s normal torture directive was ok; you _really_ had to go outside the bounds of approved torture, waterboarding, stress position, and rectal rehydration procedures, to get any consideration by the investigation.

In stating “the Department has declined prosecution because the admissible evidence would not be sufficient to obtain and sustain a conviction beyond a reasonable doubt” it suggests a standard for CIA personnel perhaps slightly different from how DoJ might handle if you or some random person on the street did similar acts.

Oh, I am QUITE aware of Holder’s views on this. “Befehl ist Befehl . . .”

But the key words in your last quote are these: “the admissible evidence.” This suggests that there is evidence, but it is — for whatever reason — deemed to be inadmissible. Perhaps the CIA would not allow it to be disclosed, even in camera and under seal, because it would reveal programs and procedures deemed essential to national security. Perhaps the DOJ would not allow it to be disclosed, even in camera and under seal, because it would raise executive privilege issues. Or perhaps, just perhaps, John Durham does not understand the meaning of the word “admissible” when it might implicate GOP leaders as complicit in illegal activities.

There’s two loaded issues DoJ plays games with. You covered the various ways “admissibility” can be fraught pretty well.

But also the “…reasonable…” standard is not quite so uniformly applied either by those fortunate enough to be blessed with federal prosecution; how reasonable is it that the national Registry of Exonerations has more than 2,500 names of bona fide innocent people, 97% of whom were wrongfully convicted of rape or murder, 25% coerced to wrongfully confess, and 11% wrongfully pushed to pleading guilty — spending an average of 14 years in prison–10% of whom spent 25 years or more in prison for crimes they didn’t commit. Maybe DoJ should apply CIA standard to all prior to arrest, or start applying their normal standard to crimes committed for and by government.

And I even gave the DOJ the prosecution’s opening statement for the torture trial.

Part of the problem is human nature. We are pretty much hard-wired for narratives, we understand the world by telling stories about it. And stories have structure; and heroes and villains; and so when reporters construct stories, it is very hard to avoid having those stories reflect the narrative structures we absorb every day as we grow up; they get cemented in place. Yes, of course, reporters are supposed to get the facts and then tell the story that the facts give them. But there is is this gravitational pull, always, to have the facts fit the story structure. Your own reporting, Dr W, is the best example I know of reporting the facts and fitting the story around the facts. Often these are complex stories that don’t fit into standard narrative patterns. And like I said, there is always this gravitational tug of – not so much assumptions, but simply of expecting that the stories out there in the world will conform to type, to expectations. And once a tale is locked in place, it takes a lot of effort to tell it differently, even when the facts are available for reporters to see. The Grueskin piece (which struck me as pretty self-congratulatory in some ways) is a good example.

Thanks–I’m sure I’m little better than others at sticking to the facts. But I agree that this is about narrative. And Durham is using to his advantage that he gets to tell stories in a certain way.

Regardless of how well you stick to the facts (I agree with JPJ btw), you absolutely excel at exposing when others do not.

“…he gets to tell stories in a certain way…”

When I read this I saw air quotes around “tell stories.”

I think that is the best way to put it for now but in reality he’s pretty much an equal to the dossier in terms of goals and impact.

I don’t disagree about the appeal of narratives, but I don’t find it a sufficient explanation for the media’s ongoing failures.

There is a huge story here — it’s about a runaway prosecutor embedded by a vicious former Attorney General fabricating an attack on a long list of foes. It’s an easy narrative to tell.

But the DC press hates telling stories that exonerate Democrats and villifies the GOP, even when they’re true.

You can look at Covid and see how hard the press has dodged the obvious narrative that Trump and the GOP have worked overtime in ways that have needlessly killed tens, if not hundreds of thousands, while Biden and the Democrats have launched a successful vaccination program in spite of huge GOP headwinds.

It’s a running narrative that could inform story after story on the particulars of the Covid fight. But then you can see the weird passive voice, anti-narrative at work in this recent NPR piece which goes out of its way to avoid attributing any agency behind the rise in cases.

https://www.npr.org/2021/11/15/1055936639/covid-19-cases-are-rising-again-in-the-u-s

And that same reluctance is what has turned the Durham story into an anti-narrative, which removes any GOP agency behind a weird, sloppy, vindictive effort, and leaves audiences scratching their heads about what is really going on. There’s a story to tell, but institutional bias prevents the press from telling it, even when it’s newsworthy and engaging.

“ Part of the problem is human nature. We are pretty much hard-wired for narratives, we understand the world by telling stories about it. And stories have structure; and heroes and villains; and so when reporters construct stories, it is very hard to avoid having those stories reflect the narrative structures we absorb every day as we grow up; they get cemented in place.”

Yep.

Trial lawyering 101: “He/she with the best story, wins.”

Why do humans “reason?” To WIN the argument. If truth happens along the way, so much the better.

There is definitely that.

And there is also tracking and applied engineering where stronger stories get you close to your prey and have the throwing stick well enough shaped to allow you to kill the animal successfully.

Hey emptywheel, have you made Durham’s Christmas card list yet?

Almost none of them ever bothered to really understand what was going on with Trump and Russia in the first place, so it was easy for them to get stuck just relaying allegations and then counterallegations.

A huge problem is at the editorial level. I don’t think any of the outlets assigned a dedicated team or even reporter to even getting to a handle on it — the mishmash of bylines at the NY Times, Washington Post, CNN, etc., and the wide range of other issues covered by those reporters, was an indication of how fractured the institutional understanding was, and how little priority their management assigned to it.

Which was nuts — it was obviously a huge story, and one that was going to need focus, and one that could have paid more substantial dividends in news value than anything in Podesta’s 2016 emails. Instead, the NY Times had more reporters bumbling through diners or reading Twitter critics than they did focused on Trump-Russia.

So of course, when Barr completely mischaracterized Mueller’s report, or now with Durham being embarassingly sloppy and hackish, there is nobody in house at major outlets who could catch obvious errors and correctly characterize what was going on.

The GOP knows that nobody is really on the case outside of certain beats, like David Fahrenthold, and they’ve been filling all of the gaps with nonsense, knowing that the vast numbers of generalist reporters are easily duped, because they ultimately feel that serious source based reporting and analysis is beneath them.

I can recall president Nixon complaining of “left wing media bias” and then president Reagan using that catch phrase even more. I think he pretty successfully neutered NPR by making their funding from the government contingent on their neutrality. Of course neutrality is in the eye of the beholder in this case.

When an indictment misspells the name of the person being indicted, how much can we rely upon that indictment to be professional, honest, and complete? If I turned in a college paper about a famous medieval poet, and didn’t get that poet’s name spelled correctly every single time I mentioned that name, would I still expect to get an A?

No, I would not. And if the professor didn’t catch that I misspelled the name of the subject of my paper, I would think my prof was pretty incompetent over all. If I was in jail based upon a document that didn’t get my name correct, I would be appealing, asking for the indictment to be quashed AND for my legal fees to be paid by the person leading the botched prosecution.

Just saying!

ETA: By the way, I did write a paper about a famous historical poet, got the name right every time, got the A+… just saying.

To Marcy and the whole crew. Thanks. When I read the article in WaPo, as often happens, I found myself wondering if this guy had read Emptywheel. What’s encouraging to me is that my opinion was about the same as yours, which means I’m learning!! As an old retired engineer, evidence that I’m still alive is always appreciated. Contribution to follow.

Thanks! And thanks!

Or did they bother to Google at all?

At 3:00 AM Wed. Nov. 17, Glenn Kessler of the WP, poste “Fact Checker Analysis The Steele dossier: A guide to the latest allegations.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/11/17/steele-dossier-guide-latest-allegations/

Seemed to not have had the time to check the allegations against the transcripts or summaries as done here. Look forward to Marcy’s analysis.

I

Kessler is a dope.

It’s abundantly clear he takes a lot of what he writes almost straight from people in the PR industry, with a minimum of rewrites to appear like it’s his work.

His editors have to know what he’s been doing at this point — no way does this kind of hackery persist in DC without people complaining about how he operates, but they don’t care.

Kessler is Kessler. Has been for a long time now.

And, also:

BRET STEPHENS, The Federal Bureau of Dirty Tricks, Nov. 16, 2021.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/16/opinion/steele-dossier-fbi-trump.html

“A version of this article appears in print on Nov. 17, 2021, Section A, Page 21 of the New York edition with the headline: The Federal Bureau of Dirty Tricks.”

Stephens is also a dope.

(h/t bmaz)

Very much so.

My impression of Stephens is not as kind and understated.

The appearance of all of these pieces at once with so many similar talking points makes it clear that there is a coordinated PR effort going on with multiple players pushing a narrative.

It wouldn’t kill anyone to decide to report on the spin campaign and who is behind it instead of amplifying it, would it?

The clicks and engagement from challenging the PR would actually be better than writing piece #26 in a crowded field. It’s not like these guys are getting an exclusive at this point.

But none of these hacks actually care about standing out in their field, they want to sink to the lowest common denominator. And admitting that they are only recycling bullet points and don’t know how to cover an issue would cause them to look even worse than they already do, so why bother?

Perhaps Durham’s sloppiness is an indication that he’s become bored and his heart really isn’t in his job anymore. At the time he began his investigation, he may have felt motivated by the desire to find a way to exonerate Trump and discredit Hillary Clinton and the Democrats, but after Trump’s horrendous bungling of the Covid-19 pandemic and his thwarted coup attempt this past January, Durham may be thinking that going back five years or so to delve into the entrails of the Russia investigation is now kind of pointless, at least as far as the MAGA crowd is concerned. For them, he might as well be talking about the origins of the Peloponnesian War.

The folks who believe in Jewish space lasers, lizard people, and the resurrection of JFK Jr. aren’t going to be much interested in wading through the arcane details of Durham’s accounts of who said what to whom in an FBI interview almost a half decade ago. It’s a bad sign when you have to appeal to your audience by dragging Hillary Clinton into your discussion, as if she were some lumbering old Universal Pictures horror movie monster from the 1940s. Durham’s next assignment: Who really shot JR?

Durham is performing his role as a courtier. In his case, he is acting as a rear guard, to keep the pro-Trump noise level up, to create a semblance of rectitude, and to obfuscate how politicized he, Barr and others made the DoJ. His patrons and audience do not care much about accuracy. Feeding popular frenzy is more important, and that’s harder to do with a calm, competent Biden in office.

Relentlessness is a defining characteristic of the right’s propaganda. Exhaustion is an intended outcome. It deflates trust in the law, legal process, and government, which is necessary to nurture the desire for authoritarian rule. In keeping with your entertainment analogy, in a world dominated by Liberty Valance, Link Appleyard will always be a buffoon, Dutton Peabody will always get beaten up, and gawky Ranse Stoddard will never shoot straight. The only savior is Tom Doniphon, who will do whatever it takes, no matter the cost.

I think Durham’s mission wasn’t so much to exonerate Trump, but to create some noise around the leverage the Kremlin has on Trump. I never bough the “pee tape” narrative, but I do believe that are P (as in pedophilia) tapes with Trump and very likely his buddy Jeffrey Epstein that have found their ways to Moscow. (https://pt.scribd.com/doc/316341058/Donald-Trump-Jeffrey-Epstein-Rape-Lawsuit-and-Affidavits)

Durham also seems very determined to whitewash Alfa Bank’s involvement in all of the 2016 electoral interference, which makes sense since Barr worked as a lawyer for the law firm that represents Alfa Bank in the US. And now with his clean up on aisle 4 for Sergei Millian, of all people!

There is a need for the GOP to keep the complex machinery of data and money laundering in place to be used in future elections. And it goes beyond Russia.

The sloppiness in these indictments is a tell, though…

Thanks, rose–and earlofhuntingdon, too–for giving me the benefit of your information and insight.

This may be the best (as in most helpful) post you’ve written on Durham yet. It’s all stuff you’ve winkled out from your mastery of the documents in prior posts. But it puts it all together with linkages among the pieces. A big thank you for assembling the whole mess.

The only bit that’s missing — and I understand why you left it out of this post since you’re challenging the US media to do their jobs and get to grips with what is actually known and what needs more reporting — is Durham’s larger narrative (Sussman + Dolan + job-seeker Galina) that “Russiagate” was all Hillary’s nefarious doing.

Still, truly outstanding work!

Ah… I forgot about the other bit your analysis of Durham’s indictment doesn’t deal with. It calls for some speculation, but WHY would Danchenko lie to the FBI? As I understand the posture of the interviews, he was getting immunity as long as he didn’t lie. What motive would he have for the alleged lies – both charged and uncharged?

There’s no indication in Durham’s speaking indictment that the alleged lies were protecting someone or covering up some nefarious relation he had, whether the someone is identified/alluded to or not (yet) mentioned. None of the alleged lies would throw the FBI off the piste that connects the dossier to the DNC or its representatives, if that’s where Durham is trying to get to. Is Danchenko supposed to have blown up his immunity just because he was too embarrassed to admit how much he’d been fluffing?