DOJ’s Failures to Follow Media Guidelines on the WaPo Seizure

I wanted to add a few data points regarding the report that DOJ subpoenaed records from three WaPo journalists.

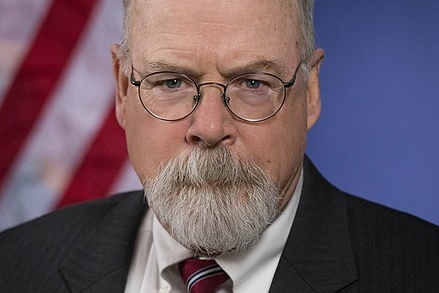

This post is premised on three pieces of well-justified speculation: that John Durham, after having been appointed Special Counsel, obtained these records, that Microsoft challenged a gag, and that Microsoft’s challenge was upheld in some way. I’m doing this post to lay out some questions that others should be asking about what happened.

An enterprise host (probably Microsoft) likely challenged a gag order

The report notes that DOJ did obtain the reporters’ phone records, and tried, but did not succeed, in obtaining their email records.

The Trump Justice Department secretly obtained Washington Post journalists’ phone records and tried to obtain their email records over reporting they did in the early months of the Trump administration on Russia’s role in the 2016 election, according to government letters and officials.

In three separate letters dated May 3 and addressed to Post reporters Ellen Nakashima and Greg Miller, and former Post reporter Adam Entous, the Justice Department wrote they were “hereby notified that pursuant to legal process the United States Department of Justice received toll records associated with the following telephone numbers for the period from April 15, 2017 to July 31, 2017.” The letters listed work, home or cellphone numbers covering that three-and-a-half-month period.

[snip]

The letters to the three reporters also noted that prosecutors got a court order to obtain “non content communication records” for the reporters’ work email accounts, but did not obtain such records. The email records sought would have indicated who emailed whom and when, but would not have included the contents of the emails. [my emphasis]

What likely happened is that DOJ tried to obtain a subpoena on Microsoft or Google (almost certainly the former, because the latter doesn’t care about privacy) as the enterprise host for the newspaper’s email service, and someone challenged or refused a request for a gag, which led DOJ to withdraw the request.

There’s important background to this.

Up until October 2017, when the government served a subpoena on a cloud company that hosts records for another, the cloud company was often gagged indefinitely from telling the companies whose email (or files) it hosted. By going to a cloud company, the government was effectively taking away businesses’ ability to challenge subpoenas themselves, which posed a problem for Microsoft’s ability to convince businesses to move everything to their cloud.

That’s actually how Robert Mueller obtained Michael Cohen’s Trump Organization emails — by first preserving, then obtaining them from Microsoft rather than asking Trump Organization (which was, at the same time, withholding the most damning materials when asked for the same materials by Congress). Given what we know about Trump Organization’s incomplete response to Congress, we can be certain that had Mueller gone to Trump Organization, he might never have learned about the Trump Tower Moscow deal.

In October 2017, in conjunction with a lawsuit settlement, Microsoft forced DOJ to adopt a new policy that gave it the right to inform customers when DOJ came to them for emails unless DOJ had a really good reason to prevent Microsoft from telling their enterprise customer.

Today marks another important step in ensuring that people’s privacy rights are protected when they store their personal information in the cloud. In response to concerns that Microsoft raised in a lawsuit we brought against the U.S. government in April 2016, and after months advocating for the United States Department of Justice to change its practices, the Department of Justice (DOJ) today established a new policy to address these issues. This new policy limits the overused practice of requiring providers to stay silent when the government accesses personal data stored in the cloud. It helps ensure that secrecy orders are used only when necessary and for defined periods of time. This is an important step for both privacy and free expression. It is an unequivocal win for our customers, and we’re pleased the DOJ has taken these steps to protect the constitutional rights of all Americans.

Until now, the government routinely sought and obtained orders requiring email providers to not tell our customers when the government takes their personal email or records. Sometimes these orders don’t include a fixed end date, effectively prohibiting us forever from telling our customers that the government has obtained their data.

[snip]

Until today, vague legal standards have allowed the government to get indefinite secrecy orders routinely, regardless of whether they were even based on the specifics of the investigation at hand. That will no longer be true. The binding policy issued today by the Deputy U.S. Attorney General should diminish the number of orders that have a secrecy order attached, end the practice of indefinite secrecy orders, and make sure that every application for a secrecy order is carefully and specifically tailored to the facts in the case.

Rod Rosenstein, then overseeing the Mueller investigation, approved the new policy on October 19, 2017.

The effect was clear. When various entities at DOJ wanted records from Trump Organization after that, DOJ did not approve the equivalent request approved just months earlier.

If DOJ withdrew a subpoena rather than have it disclosed, it was probably inconsistent with media guidelines

If I’m right that DOJ asked Microsoft for the reporters’ email records, but then withdrew the request rather than have Microsoft disclose the subpoena to WaPo, then the request itself likely violated DOJ’s media guidelines — at least as they were rewritten in 2015 after a series of similar incidents, including DOJ’s request for the phone records of 20 AP journalists in 2013.

DOJ’s media guidelines require the following:

- Attorney General approval of any subpoena for call or email records

- That the information be essential to the investigation

- DOJ has taken reasonable attempts to obtain the information from alternate sources

Most importantly, DOJ’s media guidelines require notice and negotiation with the affected journalist, unless the Attorney General determines that doing so would “pose a clear and substantial threat to the integrity of the investigation.”

after negotiations with the affected member of the news media have been pursued and appropriate notice to the affected member of the news media has been provided, unless the Attorney General determines that, for compelling reasons, such negotiations or notice would pose a clear and substantial threat to the integrity of the investigation, risk grave harm to national security, or present an imminent risk of death or serious bodily harm.

But a judge can review the justifications for gags before issuing them (for all subpoenas, not just media ones).

Just as an example, the government obtained a gag on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and Google when obtaining Reality Winner’s cloud-based communications a week after they had arrested her (at a time when she was in no position to delete her own content). After a few weeks, Twitter challenged the gag. A judge gave DOJ 180 days to sustain the gag, but in August 2017, DOJ lifted it.

That was a case where DOJ obtained the communications of an accused leaker, with possible unknown co-conspirators, so the gag at least made some sense.

Here, by contrast, the government would have been asking for records from journalists who were not alleged to have committed any crime. The ultimate subject of the investigation would have no ability to destroy WaPo’s records. The records — and the investigation — were over three years old. Whatever justification DOJ gave was likely obviously bullshit.

Hypothetical scenario: DOJ obtains cell phone records only to have a judge rule a gag inappropriate

Let me lay out how this might have worked to show why this might mean DOJ violated the media guidelines. Here’s one possible scenario for what could have happened:

- In the wake of the election, John Durham subpoenaed the WaPo cell providers and Microsoft, asking for a gag

- The cell provider turned over the records with no questions — neither AT&T nor Verizon care about their clients’ privacy

- Microsoft challenged the gag and in response, a judge ruled against DOJ’s gag, meaning Microsoft would have been able to inform WaPo

That would mean that after DOJ, internally — Billy Barr and John Durham, in this speculative scenario — decided that warning journalists would create the same media stink we’re seeing today and make the records request untenable, a judge ruled that that a media stink over an investigation into a 3-year old leak wasn’t a good enough reason for a gag. If this happened, it would mean some judge ruled that Barr and Durham (if Durham is the one who made the request) invented a grave risk to the integrity of their investigation that a judge subsequently found implausible.

It would mean the request itself was dubious, to say nothing of the gag.

Once again, DOJ failed to meet its own notice requirements

And with respect to the gag, this request broke another one of the rules on obtaining records from reporters: that they get notice no later than 90 days after the subpoena. The Justice Manual says this about journalists whose records are seized:

- Except as provided in 28 C.F.R. 50.10(e)(1), when the Attorney General has authorized the use of a subpoena, court order, or warrant to obtain from a third party communications records or business records of a member of the news media, the affected member of the news media shall be given reasonable and timely notice of the Attorney General’s determination before the use of the subpoena, court order, or warrant, unless the Attorney General determines that, for compelling reasons, such notice would pose a clear and substantial threat to the integrity of the investigation, risk grave harm to national security, or present an imminent risk of death or serious bodily harm. 28 C.F.R. 50.10(e)(2). The mere possibility that notice to the affected member of the news media, and potential judicial review, might delay the investigation is not, on its own, a compelling reason to delay notice. Id.

- When the Attorney General has authorized the use of a subpoena, court order, or warrant to obtain communications records or business records of a member of the news media, and the affected member of the news media has not been given notice, pursuant to 28 C.F.R. 50.10(e)(2), of the Attorney General’s determination before the use of the subpoena, court order, or warrant, the United States Attorney or Assistant Attorney General responsible for the matter shall provide to the affected member of the news media notice of the subpoena, court order, or warrant as soon as it is determined that such notice will no longer pose a clear and substantial threat to the integrity of the investigation, risk grave harm to national security, or present an imminent risk of death or serious bodily harm. 28 C.F.R. 50.10(e)(3). In any event, such notice shall occur within 45 days of the government’s receipt of any return made pursuant to the subpoena, court order, or warrant, except that the Attorney General may authorize delay of notice for an additional 45 days if he or she determines that for compelling reasons, such notice would pose a clear and substantial threat to the integrity of the investigation, risk grave harm to national security, or present an imminent risk of death or serious bodily harm. Id. No further delays may be sought beyond the 90‐day period. Id. [emphasis original]

Journalists are supposed to get notice if their records are seized. They’re supposed to get notice no later than 90 days after the records were obtained. AT&T and Verizon would have provided records almost immediately and this happened in 2020, meaning the notice should have come by the end of March. But WaPo didn’t get notice until after Lisa Monaco was confirmed as Deputy Attorney General and, even then, it took several weeks.

DOJ’s silence about an Office of Public Affairs review

While it’s not required by guidelines, in general DOJ has involved the Office of Public Affairs in such matters, so someone who has to deal with the press can tell the Attorney General and the prosecutor that their balance of journalist equities is out of whack. At the time, this would have been Kerri Kupec, who was always instrumental in Billy Barr’s obstruction and politicization.

But it’s not clear whether that happened. I asked Acting Director of OPA Marc Raimondi (the guy who has defended what happened in the press; he was in National Security Division at the time of the request), twice, whether someone from OPA was involved. Both times he ignored my question.

The history of Special Counsels accessing sensitive records and testimony

There’s a history of DOJ obtaining things under Special Counsels they might not have obtained without the Special Counsel:

- Pat Fitzgerald coerced multiple reporters’ testimony, going so far as to jail Judy Miller, in 2004

- Robert Mueller obtained Michael Cohen’s records from Microsoft rather than Trump Organization

- This case probably represents John Durham, having been made Special Counsel, obtaining records that DOJ did not obtain in 2017

There’s an irony here: Durham has long sought ways to incriminate Jim Comey, who is represented by Pat Fitzgerald and others. In 2004, as Acting Attorney General, Comey approved the subpoenas for Miller and others. That said, given the time frame on the records request, it is highly unlikely that he’s the target of this request.

Whoever sought these records, it is virtually certain that the prosecutor only obtained them after making decisions that DOJ chose not to make when these leaks were first investigated in 2017, after Jeff Sessions announced a war on media leaks in the wake of having his hidden meeting with Sergey Kislyak exposed.

That suggests that DOJ decided these records, and the investigation itself, were more important in 2020 than Jeff Sessions had considered them in 2017, when his behavior was probably one of the things disclosed in the leak.

The dubious claim that these records could have been necessary or uniquely valuable

Finally, consider one more detail of DOJ’s decision to obtain these records: their claims, necessary under the media policy, that 3-year old phone and email records were necessary to a leak investigation.

When these leaks were first investigated in 2017, DOJ undoubtedly identified everyone who had access to the Kislyak intercepts and used available means — including reviewing the government call records of the potential sources — to try to find the leakers. If they had a solid lead on someone who might be the leaker, the government would have obtained the person’s private communication records as well, as DOJ did do during the contemporaneous investigation into the leak of the Carter Page FISA warrant that ultimately led to SSCI security official James Wolfe’s prosecution.

Jeff Sessions had literally declared war within days of one of the likely leaks under investigation here, and would approve a long-term records request from Ali Watkins in the Wolfe investigation and a WhatsApp Pen Register implicating Jason Leopold in the Natalie Edwards case. After Bill Barr came in, he approved the use of a Title III wiretap to record calls involving journalists in the Henry Frese case.

For the two and a half years between the time Sessions first declared war on leaks and the time DOJ decided these records were critical to an investigation, DOJ had not previously considered them necessary, even at a time when Sessions was approving pretty aggressive tactics against leaks.

Worse still, DOJ would have had to claim they might be useful. These records, unlike the coerced testimony of Judy Miller, would not have revealed an actual source for the stories. These records, unlike the Michael Cohen records obtained via Microsoft would not be direct evidence of a crime.

All they would be would be leads — a list of all the phone numbers and email addresses these journalists communicated with via WaPo email or telephony calls or texts — for the period in question. It might return records of people (such as Andy McCabe) who could be sources but also had legal authority to communicate with journalists. It would probably return a bunch of records of inquiries the journalists made that were never returned. It would undoubtedly return records of people who were sources for other stories.

But it would return nothing for other means of communication, such as Signal texts or calls.

In other words, the most likely outcome from this request is that it would have a grave impact on the reporting equities of the journalists involved, with no certainty it would help in the investigation (and an equally high likelihood of returning a false positive, someone who was contacted but didn’t return the call).

And if it was Durham who made the request, he would have done so after having chased a series of claims — many of them outright conspiracy theories — around the globe, only to have all of those theories to come up empty. Given that after years of investigation Durham has literally found nothing new, there’s no reason to believe he had any new basis to think he could solve this leak investigation after DOJ had tried but failed in 2017. Likely, what made the difference is that his previous efforts to substantiate something had failed, and Barr needed to empower him to keep looking to placate Trump, and so Durham got to seize WaPo’s records.

Billy Barr has been hiding other legal process against journalists

Given the disclosure that Barr approved a request targeting the WaPo about five months ago and that under Barr DOJ used a Title III wiretap in a leak investigation (albeit targeting the known leaker), it’s worth noting one other piece of oversight that has lapsed under Barr.

In the wake of Jeff Sessions declaring war on leaks in 2017 (and, probably, the leak in question here), Ron Wyden asked Jeff Sessions whether the war on leaks reflected a change in the new media guidelines adopted in 2015.

Wyden asked Sessions to answer the following questions by November 10:

- For each of the past five years, how many times has DOJ used subpoenas, search warrants, national security letters, or any other form of legal process authorized by a court to target members of the news media in the United States and American journalists abroad to seek their (a) communications records, (b) geo-location information, or (c) the content of their communications? Please provide statistics for each form of legal process.

- Has DOJ revised the 2015 regulations, or made any other changes to internal procedures governing investigations of journalists since January 20, 2017? If yes, please provide me with a copy.

In response, DOJ started doing a summary of the use of legal process against journalists for each calendar year. For example, the 2016 report described the legal process used against Malheur propagandist Pete Santilli. The 2017 report shows that, in the year of my substantive interview with FBI, DOJ obtained approval for a voluntary interview with a journalist before the interview because they, “suspected the journalist may have committed an offense in the course of newsgathering activities” (while I have no idea if this is my interview, during the interview, the lead FBI agent also claimed to know the subject of a surveillance-related story I was working on that was unrelated to the subject of the interview, though neither he nor I disclosed what the story was about). The 2017 report also describes obtaining Ali Watkins’ phone records and DOJ’s belated notice to her. The 2018 report describes getting retroactive approval for the arrest of someone for harassing Ryan Zinke but who claimed to be media (I assume that precedent will be important for the many January 6 defendants who claimed to be media).

While I am virtually certain the reports — at least the 2018 one — are not comprehensive, the reports nevertheless are useful guidelines for the kinds of decision DOJ deems reasonable in a given year.

But as far as anyone knows, DOJ stopped issuing them under Barr. Indeed, when I asked Raimondi about them, he didn’t know they existed (he is checking if they were issued for 2019 and 2020).

So we don’t know what other investigative tactics Barr approved as Attorney General, even though we should.

My flabbers are ghasted that WaPo (any media org) would have an email system that firstly was out of their control in terms of 2nd party retention (host your own is the only way), and secondly didn’t have a very robust deletion policy.

It was cheaper to run an exchange server on Microsoft 365. Pennywise and pound foolish.

Microsoft and Google also offer security that WaPo can’t do on their own.

And that would be even more of a concern for the Washington Post after the murder of Jamal Khashoggi.

Really good point.

Reporters will move to safer means of communicating when they feel it’s necessary. So it’s not automatically a problem in the case of DOJ just wanting numbers and times of calls.

It can get to be a bigger problem if someone gets the meatier parts of emails — if I was ever a source, I’d want to know how reporters communicated with editors and how editorial discussions were handled to avoid leaving email evidence. The best reporter-source methods don’t mean much if the rest of the food chain is a problem. And to be fair, better outfits have ways to handle these issues.

Even in my early years as a legal secretary (1980), we were always counseled not to put anything in writing that we wouldn’t want to see printed on the front page of the NYT.

It’s more than a little unfair to suggest, even by inference, that ‘Google doesn’t care about privacy. They do not share data the way Facebook does, though it is true they don’t fight government intrusion the way Apple does and in this instance, Microsoft. Google hoards the personal data for itself, and yields only such information as is needed to serve ads, cartographic, and shopping links – sensitive information they don’t sell.

Compared to facebook or your ISP, this a distinction with a huge difference. Every reporter knows this already and they use multiple layers of precaution (vpns, encryption, burner devices).

Note: I have no official relationship with Google but I administer a couple client Google Analytics sites where some metadata is available. (I also used to do Facebook analytics until I swore off in Nov ’16. There is no attempt whatsoever to protect users. Advertisers can target a single individual.)

Giggle may have a different business model than FB, but I don’t think it is unfair to suggest, even by inference, that its concern for privacy is, to misquote the bard, more honored in the breach than in the observance.

A routine public critique of privacy concerns about Giggle.

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/may/09/how-private-is-your-gmail-and-should-you-switch

The lack of furor over what seems to be a gross infringement of the freedom of the press and of speech is disturbing. We are letting our freedom and liberties fall away inch by inch, step by step and soon….. Niagara Falls!!!!

Thanks to Dr Marcy for going into the details. May someone who isn’t banned from TV for saying “naughty” words out loud carry her work into the wider public discussion.

Jumping here to highlight an aspect of Dr. Marcy’s work that I am most grateful for. Prodigious encyclopedic ingestion of disclosed details IS matched by her investigative agency. She pries pieces* of the puzzle that the power-over actors do not want us to perceive.

“I asked Acting Director of OPA Marc Raimondi (the guy who has defended what happened in the press; he was in National Security Division at the time of the request), twice, whether someone from OPA was involved………”

*Pieces, that ought to inspire our own legislative advocacy

I’m curious if the fact that the DOJ/Durham subpoena is revisiting such well visited grounds from previous leak searches means that he isn’t really after substance. Is it possible he is just trying to hit someone with professional and/or legal penalties for failing to account for communications with the press while being questioned?

I guess one counterargument might be that Trump’s DOJ would have the motive to have gone after people in this manner already.

That was my assumption — find any dirt that can be used to smear the Mueller investigation, regardless of whether it had any meaningful bearing upon the merits for appointing the Special Prosecutor.

It does make me wonder what Durham’s real goal is here since it is clear that Biden is not going anywhere, and anything Durham does dig up will be fairly evaluated by AG Garland and in the vast majority of cases (if not all) consigned to the scrap heap. These kinds of transgressions involving Barr and Durham might become a serious liability, so these questions come to mind:

1. Is it possible to prosecute Durham for abuse of power in his investigation, especially in such a way as to minimize the chances of the GOP returning the favor later? What particular actions would force an impeachment or indictment?

2. What does DJT and/or Billy Barr have on Durham to make him continue this witch hunt that has gone nowhere, and any discovery of sources would be useless since DJT is out of power. FWIW I do not think Biden’s WH is likely to engage in this kind of petty revenge. But, let’s note from EW’s narrative above that 2013 was during Obama’s administration, so it is possible that both parties would be interested in who talked to whom in the press.

3. It seems clear that Billy Barr (whose book might add some more “statements against interest”) is up to his eyeballs in legal liability alligators to the point that federal judges are questioning his integrity in writing. Would Barr’s prosecution be so politically sensitive that AG Garland wouldn’t touch it unless there is a trigger that forces action? What might that trigger be?

1) No. There is literally nothing evidenced that would even remotely support prosecution; Durham is effectively immune anyway.

2) There is no evidence whatsoever that Durham, at this point, is being influenced by Trump or Barr. This is conspiracy level thought.

3) Yes, that would be so politically, not to mention legally, “sensitive” (actually toxic) that it will not happen. There really is no such trigger, neither Biden nor Garland want any part of this. It is vapor.

Kind of what I thought, but it was worth bouncing out so everyone sees why it’s not viable to “go there” because someone else will do that.

Hey, I’d be thrilled, just not seeing it. Half understand why, but still it is painful.

You say “Durham, at this point, is [not] being influenced by Trump or Barr.” These phone records were seized during Barr’s tenure as AG. Do you believe Durham is actually serving any purpose now, except to maintain the appearance that the Biden administration is not discontinuing a Trumpist investigation/fishing expedition/conspiracy theory?

I will stick with exactly what said.

There is “grave impact” only when word of the records subpoena becomes public. If no one knows that the journalists’ records have been accessed — neither the reporters nor the sources — then potential future sources have no particular reason to be more worried about talking to reporters.

Make no mistake here: the DOJ wants to make this public, but they wanted to do so by indicting past leakers. If they don’t indict anyone (and no one leaks the fact they asked for these records), then there’s no chilling effect on the press.

All this leaves me wondering about the letters sent to the WaPo reporters, informing them that their records had been accessed. Is this an effort to quell future leaks by making the past access of journalists’ phone and email records public (since indictments are not apparently forthcoming), or is it career DOJ folks trying to come clean with some less-than-savory subpoenas during the Trump era?

These are two very different propositions, and I don’t know which I find more likely.

I’m not so sure it would if the reporters are properly motivated. Let’s look at the inverse, the OANN/Newsmax/Faux News world where as an example Joe Biden’s WH is being run by VP Harris or Obama according to Mr. Kelly, and nothing is happening to them yet. Neither did the reporters stop digging into Trumpworld shenanigans. They’re still a work in progress to overcome the bothsides bias, but I’m encouraged.

That depends on whether or not the government doesn’t start dropping hints to reporters that it does have access to their communication records. The stifling of dissent can start slowly… if it becomes rumored that particular reporters are under the microscope of the government then those reporters’ sources may start drying up quick. That’s just one example of how secret investigations in reporters can start to be abused by government actors. There’s also the fear factor for reporters and their families, friends, co-workers, etc, to consider too…

Just the fact that this is now public will change the way investigative journalists operate. I am fairly certain the WaPo has already taken steps to change how it protect its sources. Whatever it takes is what they will do. Without sources, there is no WaPo. There will be a work around.

Doubtful. They already knew.

Email, shmemail.

The Washington Post has a prominent securedrop link on its home page. It’s been there since June 6th, 2014, which is long before the events we are discussing here. (It’s about a year after the Snowden revelations.)

Securedrop exists for a reason.

Suppose somebody sent me a message concerning an existential threat to national security, and sent it by email, ignoring the securedrop mechanism. I would ignore it, on the grounds that the sender is a danger to himself and others, not somebody who could be trusted to send or receive anything sensitive. I would consider it a possible catfishing / entrapment exercise. I certainly wouldn’t write about it in the newspaper or anywhere else. I might fantasize about toying with the sender a little bit, asking questions like “Are all your colleagues in the TLA where you work as clueless as you when it comes to basic tradecraft?” … but I wouldn’t actually follow through on that; I would let James Veitch handle that.

========

Along similar lines: It is not worth fussing over whether they got “content” or “non-content” information. There is a proverb that says:

«Metadata is data. A cryptosystem that leaks metadata is a cryptosystem that leaks.»

In other words, a system that leaks metadata is insecure. Don’t use it for anything serious. Treat it like a public blog.

References:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/anonymous-news-tips/

James Veitch : “What happens when you reply to spam”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-9RL4RATwoY

It’s worth noting that the info Durham is looking into doesn’t necessarily follow the pattern of a source sending some big info dump to a reporter.

MW notes “[the search] might return records of people (such as Andy McCabe) who could be sources but also had legal authority to communicate with journalists.”

A huge amount of communication between reporters and government officials takes the form of things like a reporter emailing a link to a rival’s article and asking if it’s valid, and the source might just legitimately reply it’s worth checking if the budget figures work out the way the article says.

Durham may be looking for contacts that look suspicious to him in hindsight that on the surface are legit. He may also be looking to make a mountain out of a molehill. I’m not sure we can say.

Is it time to stop moaning, “I can’t believe the GOP did that,” and to stop wishing we had the GOP we want instead of dealing with the GOP we have: a fascistic authoritarian party wedded to a cult of personality, lies, racism, and the denial of any election victory but theirs? It is as if we were back in 1932, and the Reichstag fire were six months away. Thoughts and prayers alone will not change what’s coming.

“…and to stop wishing we had the GOP we want instead of dealing with the GOP we have…Thoughts and prayers alone will not sold the problem.”

Yes and this is looking more and more like 1933 Germany and we are just watching like deer with their eyes focused on the .302 that’s aimed at ‘em.

Not sure that WaPo is on MS, but it’s a lot less likely they’re on Google. Google has its own solutions that it pushes heavily for anti-spam and email security, and WaPo is using ProofPoint and possibly Cloudmark.