Democratic Values In Practice

In earlier chapters of The Public And Its Problems John Dewey described the social ideal of democracy as distinguished from the form democracy takes in an actual government. Chapter 5 begins his answer to the question how can we move from our current politics to forms closer to an ideal democracy. That could mean minor fixes to the current form, or adding similar institutions. But if the problems we need to solve exceed the capabilities of our institutions, then we may have to examine the entire structure and make major changes to produce new institutions, laws and regulations that can solve our problems.

The controlling factor must be the interest of the Public, using the term as Dewey does. Steps that bring more of a Public into the decision-making processes are improvements. That could just mean making it easier for everyone to vote, so they can participate at the level of selecting officials. It can also mean taking those interested enough into the decision-making process. That could be as simple as listening to their concerns. It could mean listening to their ideas about who should speak for them, who they trust, and to their solutions. And this isn’t just about government. For Dewey, democracy is valuable in all aspects of our social lives, work, Church, voluntary associations, and involuntary associations like Homeowners Associations.

Dewey offers the following working descriptions of democratic life:

From the standpoint of the individual, it consists in having a responsible share according to capacity in forming and directing the activities of the groups to which one belongs and in participating according to need in the values which the groups sustain. From the standpoint of the groups, it demands liberation of the potentialities of members of a group in harmony with the interests and goods which are common. P. 174-5.

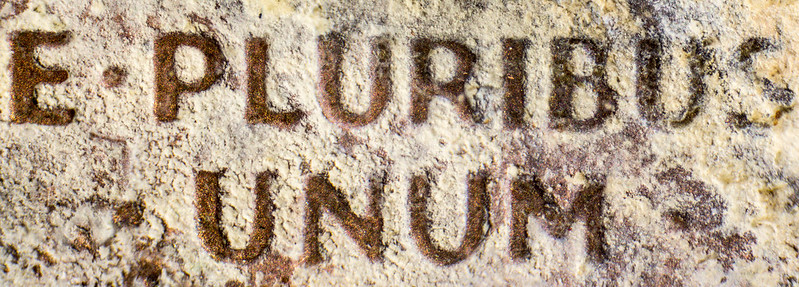

Among the characteristics of democracy are liberty, fraternity and equality. These words make no sense apart from communal life. If society is just a large group of isolated individuals, equality comes to mean merely average, leaving no room for the brilliant, the incompetent, and the uninterested. Liberty means freedom from the bonds of community, ending in anarchy. Fraternity, brotherhood, is meaningless absent community. From this Dewey concludes that democracy is meaningful only in the context of community.

In the context of a community, fraternity becomes the conscious appreciation of the common goods created by our joint efforts and which give direction to our lives. Liberty frees us to flourish, to live our best lives in the company of others, and with their assistance and encouragement. Equality becomes the share of the jointly created goods accruing to each according to need and capacity to use, unhampered by other concerns.

Dewey uses babies as a way of understanding equality. We give babies what they need, not because they’ve earned it, but because they need it or because it makes them happy. When we do this across society, we are our best selves.

Group behavior arises naturally. People work together, live together, and interact. Community arises naturally as we begin to appreciate the contributions of our neighbors and see that they appreciate our contributions. To Dewey, the key point is not the physical actions or the emotions that might attach to them, but the moral implication. By “moral” Dewey means that community life “… is emotionally, intellectually, consciously sustained.” We pay attention to each other and to ourselves in our relations with others; and our community supports our drive to become our best selves.

In an early work, The Ethics of Democracy, Dewey discusses this moral or ethical vision of democracy.

There is an individualism in democracy … it is an individualism of freedom, of responsibility, of initiative to and for the ethical ideal, not an individualism of lawlessness. In one word, democracy means that personality is the first and final reality. It admits that the full significance of personality can be learned by the individual only as it is already presented to him in objective form in society; it admits that the chief stimuli and encouragements to the realization of personality come from society; …. It holds that the spirit of personality indwells in every individual .… From this central position of personality result the other notes of democracy, liberty, equality, fraternity – words which are not mere words to catch the mob, but symbols of the highest ethical idea which humanity has yet reached – the idea that personality is the one thing of permanent and abiding worth, and that in every human individual there lies personality.

This idea, that each individual personality flourishes only in the context of society, under its guidance and inspiration, is a brilliant justification for democracy.

Discussion

1. The Republican Party is whole-heartedly committed to the view that society is a mass of isolated individuals. It’s an idea which has deep roots in the American psyche, the lonely settler, the Lone Ranger, the rugged individual, John Galt and Howard Roark, Homo Economicus, all are examples of this theory of human nature. In The Ethics Of Democracy, Dewey dismisses this theory.

Just as Dewey predicted, the consequences of treating humans as isolated grains in a huge sand pile are dire. The bulk of the Republican Party detests people who disagree with them, particularly what they call the Left, meaning anyone who sees systemic racism, gun violence, unfair taxation, crumbling infrastructure, climate change, abuse of workers, and Covid-19 as serious problems that must be solved, and can only be solved if we act as a community.

The idea of fraternity among all Americans is meaningless to the Republican Party. Equality is a sour joke, a tool to help the weak and the moochers. Liberty means freedom from laws they don’t like, and from social restraints. Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity in Dewey’s sense have no place in Republican politics or discourse. For the entire party, there are no problems that require joint action, only pseudo-problems defined in right-wing spaces: attacks on Dr. Seuss and Mr. Potato Head; unfounded and inexplicable fears of immigration, violent crime, and budget deficits. Take a look at this chart.

Dewey says that our individuality is formed by the society around us. This too is reflected in the Republican Party. Adherents are taught, and teach their children, to ignore science unless it produces results acceptable to the hall monitors at Fox News. Fighting Covid-19 restrictions, gun fetishization, attacking legislatures, these are regarded as manly and appropriate behaviors. Police attacks on random Brown and Black people, and protestors of all colors are righteous. Exactly as Dewey said, the result of hyper-individualism is anarchy.

2. Only a few politicians, mostly local, do a decent job of involving the public in matters of public policy. Think about policing. What exactly do we as a community want to accomplish with policing? I bet the answer is different on the North Side of Chicago than the South and Southwest sides. But no one ever asks, and no one cares. We just keep doing the same things and throwing money at the problems.

3. I’m imagining a series of meetings in Churches and Schools around the city where people can talk about what they want in small groups, maybe with non-ideological facilitators, maybe live-streamed; taking in reactions from the public; more meetings. Then select from among themselves two or three people to meet with other similarly selected; talking and taking the new ideas back to their groups; meeting and discussing, trying to come to grips with this complex social problem. Maybe add some professional polling or non-ideological focus groups. Surely someone has better ideas than mine.

Democracy is possible. We just have to make it happen.

I’m intrigued by that “lonely setter” example of the atomized individual that Republicans and neoliberal capitalism require, and which is the subject of much of their mythology. Neither Hollywood nor the mythology of Manifest Destiny and European colonial expansion into the American West considers the madness and psychological toll of that isolation and loneliness. (Exceptions include one character in 1972’s, Jeremiah Johnson, and 2014’s, The Homesman.)

That mythology elides, for example, one of the great American examples of communal support that was intended, in part, to combat that loneliness and political and economic isolation – the Grange Movement. Its success made it anathema to the railroad and banking trusts of the day. That mythology also ignores that no one networks better and provides more uniform social support for its members than the wealthy and the Republican hierarchy. (That’s one reason the term wing nut welfare came to pass.)

Not Hollywood, but in _Wolf_Willow_, Wallace Stegner does a good job of showing that the admirable and loathesome aspects of the pioneers are both necessary for their very survival. Thus it is senseless to venerate the admirable qualities without recognizing the essential cruelty on other side of that coin. It’s nothing explicit, but the Janus-like nature of the “lonely settler” really begins to erode the romanticism of pioneering in that book.

Commander J.J. Adams: “We’re all part monsters in our subconcious, so we have laws and religion…”

…and community.

Years ago I read an interview with Louis L’Amour in which he said that the idea of the frontier as a venue for rugged individualism was pretty much of a myth. He said that his research showed that the first thing people settling in the West did was establish the basics of an ordered society; that is, they built a church, a school, and a courthouse. The saloons, dance halls, and brothels came later.

I am reminded of Little House on the Prairie where the moment Pa’s family was happy in a small settler community, he would uproot them for the wilderness and start over. It was cruel to the family but the idea is firmly rooted in the American ethos of independence and the historic period when land was free for the taking. My own mother was born in a snow storm in a lean to on the prairie of a homestead in Montana. My own grandfather walked away from every business he started when it became successful. This personal nihilism is deep in the American psyche.

I saw videos recently of a tortoise rushing to right another tortoise that had flipped over and was stranded on its back and another surveillance cam of a small poodle falling into a swimming pool and being rescued by a lab who barked and when no one came managed to grab the poodle with its mouth and haul it out of the water where it was clearly going to drown. Surely Americans can have the empathy and community of tortoises and dogs.

“…when land was free for the taking.”

Yep, that’s part of the mythology of white America, the idea that if you can take it, you must, never mind the theft. It also reinforces the economic mythology that unrelenting resource extraction is a religious commandment, not pillage.

Interesting question about whether and how isolation – atomization in today’s parlance – reduces our inhibitions and restraint. I suspect part of the dynamic is that everything becomes justified as an act of survival. It’s as if exhausting every resource within reach – and by extension, on the planet – were not an act of self-immolation rather than enrichment.

Dewey — or rather I believe in this case Ed’s summary of Dewey — overstates the end state of liberty. In the context of American liberty, with respect to reason why men originally fought for and died to originate a new democratic republic nation, liberty was the liberty to be free from excessive tyranny.

We’d all still be happy British citizens of a satellite British satrapy if King George III hadn’t squandered his own peoples’ wealth on expeditionary military adventures against the French in Nova Scotia area, which required him to stick it to the British in the American colonies.

It’s not that liberty inherently leads to anarchy, it was more that American colonists disliked the King sucking them dry and forcing a bunch of ridiculous frivolous hurdles at the end of gunpoint and was sensitive to a new government being inclined to do similar things.

Have you even read the Declaration of Independence? There’s ample reason we’re not Canadians.

The “liberty” that they spoke of was not to create a nation free from authority, but a nation with an authority which was free from excessive tyranny.

That’s the sloganeering language of a pamphlet. “Excessive tyranny” is in the eye of the beholder.

That may be true, but we can likely agree reasonable people see the use of paper supplied only by the Crown’s homeland at excessive markup and tax under threat of death by hands of military garrison to objectively meet any reasonable definition of “excessive tyranny.”

We can say the modern contemporary analogue is choking to death someone selling two packs of cigarettes not marked by the State’s tobacco stamp depriving the State of about $1.60 in tax revenue.

Your argument seems a tad anachronistic. As Rayne points out, it misses most of the arguments set out in the Declaration of Independence. Those were largely the best face that contemporary lawyers could put on why the colonists were taking an unprecedented step. They omit, for example, some of the more self-interested economic reasons.

That bit about taxing tea, for example, was not that the tax was so onerous, but that the net result would lower the price of tea, and undercut the lucrative colonial business of smuggling it into the colonies. Columbia historian Charles Beard was an early proponent of the economic causes for American independence.

His thesis didn’t fit the prevailing view, however, of the founders – and, hence, of contemporary politicians – as disinterested Athenian elders, and he was roundly criticized by the academy for it. But his emphasis on economic motivation is essential to understanding events. They are fundamental, for example, to understanding Alexander Hamilton’s pro-big business government finance and tax policies and the importance to them of the defeating the Whiskey “Rebellion.”

What Dewey thinks is that liberty considered in the context of a socially dominant view of human nature as a group of isolated individuals eventually turns into anarchy. I think the dominant view of human nature in the Republican Party is that we are nothing more than a group of isolated individuals competing for a piece of the economic pie. I have made this argument in one form or another many times.

I also think that this view of human nature leads to anarchy. It might take the form of the Capitol Insurrection. It might take the form of massive voter suppression, of lying and dissembling, of ignoring social problems that don’t affect Republicans, or Trumpian authoritarianism justified by the Mob Party. I agree with Dewey that democracy cannot exist in this context.

What Dewey and your argument understates is that the “frontiersmen” were not isolated individuals. They were homesteaders who if not bringing entire small communities of likeminded individuals, was at least a large and typically extended family. And the groups of those families or that community was not in competition with other families or communities but rather relied on each other, at least until commercial interests began to outweigh simple survival.

That argument seems to ignore that the population was small and isolated, the American landscape is vast, and the pace of travel painfully slow. Those on the colonial frontier were there because they had few resources but their own labor. Disease, luck, and weather were unpredictable and unmediated. And the grind of handwork in an early industrial society was unrelenting.

True, but the key distinction is that the problems associated to bona fide “isolated individuals” — loneliness, depression, unchecked mental illness leading to extreme behavior — don’t apply or apply differently to homesteads comprised of multiple individuals. Yes, there’s cases of collective dementia, cults, or the like, but my root point is that what is characterized as “group of isolated individuals” was and is really “group of isolated groups” — much has been made of familial voting blocs; husbands and wives voting together rightly, or wrongly for or against democratic goals of the collective nation. Although we’re seeing those familial, spousal, or community bonds destabilized probably more-so now than any time perhaps as far back as Civil War.

I disagree with your premise and your sense of what constituted isolation for white settlers in the various 19th century colonial frontiers. Isolated farmsteads on the Midwestern prairie “sea” in 1850 had little of the community one might associate with, say, settled agricultural Amish communities in eastern Pennsylvania or Ohio.

Physical and psychological isolation are not the same thing, a truism amply illustrated by contemporary examples of PTSD and domestic abuse.

We’re at least agreed on your final point.

Conditions in Midwest turned corner with end to Blackhawk War which had victorious US force all local tribes in Mississippi Valley of IL & IA to the West of the Mississippi, opening up safe frontier to Dubuque.

The Midwest frontier settled from mid-1830s through late 1800’s was comprised primarily of second-rounders — not gutsy enough to homestead in the midst of belligerence with indigenous peoples, and not stern enough to hack it out in virgin territory. Chicago was a safe haven. By 1860, Chicago was 9th largest US city, and relatively quick travel to the growing frontier.

Midwestern settlers weren’t soft people by any means. But by about 1850 on, they faced little of the dangers other homesteaders faced.

The roots of what would become the emergent white flight suburbs in the next century were all being established throughout the midwest, 1840-1900.

What do you mean by “midwestern”? Your generalizations here seem to apply, if at all, to places like southern Indiana and Illinois. The northern midwest, which was mainly settled in the latter half of the 19th century by northern European immigrants, posed challenges (climate, arable land) that few could withstand.

We still don’t agree, but that’s OK. Your argument about white flight seems a tad reductionist. Your description of 1850s settlers as not being “gutsy enough” focuses on the threat from Native Americans. It ignores assaults on the psyche from unrelenting handwork, ignorance, the desperation of living hand-to-mouth, and isolation. Nor am I sure that Upton Sinclair’s stockyard and meat packing workers would consider the depradations of early food barons less of an assault than those of dispossessed Native Americans.

The threat wasn’t primarily from Native Americans per se, but foreign-incited proxy warfare by the British using Native Americans still into this period.

Tread carefully here with colonial mindset.

A focus on the Great Game avoids dealing with the lived experience of would be immigrant settlers in, say, the Great Plains east of the Front Range. More damningly, it ignores the lived experience of indigenous peoples, whether in Afghanistan, the Mohawk Valley or the Upper Great Plains. Beside, after the American unCivil War, the locus of US-British rivalry in the Western Hemisphere shifted to the Caribbean and Latin America.

Hollywood kept the dream alive. But the reality was different. Between 1844 and 1860 shared news and shared publications came into being. A trip to the state capital was easier. And most of the nation within a day’s train ride of Washington, D.C. There was a community and for much of their history both political parties functioned in trying to persuade that community to vote for their candidates.

Something happened to the US part of the American psyche. Between Vietnam and Reagan, the nation forgot itself.

I think you overstate the pace of travel – and what was expected of it – and understate the regionalness of the vast majority of people. Most people did not travel beyond their local town or regional hub until after WWI. Many communities were sidestepped by the RRs altogether. Determining routes and which towns along them had stops was an intense, often corrupt game. Regionalness dominated one’s sense of community until the mid-20th century, breaking down owing to the social pressures from taking the country to war, starting with the Spanish-American War, and then the civil rights movement. News and newspapers had a similar trajectory.

In the 19th century, RRs were expensive, especially for farmers’ freight, because of monopoly practices, lack of regulation, and corruption of state and federal officials. Regional lines, say, NYC to Albany, were well-developed, but inter-regional routes were not routine until the 1870s and later.

RR were also subject to frequent disruption. RR development focused more on investor manipulation and PR than on the real economy of lines, roadbeds, machinery and the sourcing of raw materials and subsystems, and complex scheduling. And that’s before their consolidation, ultimately under J.P. Morgan. The first transcontinental lines were built by the mid-1860s, for example, but had to be frequently rebuilt, because speed of construction was considered vastly more important to capital than the quality of the built roads.

This was interesting. Thanks for posting it.