Reviews of The Deficit Myth

Posts in this series

The Deficit Myth By Stephanie Kelton: Introduction And Index

Debunking The Deficit Myth

MMT On Inflation

Reflections On The Deficit Myth

The National Debt Is Soooooo Big

The Wonkish Myth Of Crowding Out

MMT On International Trade

Social Security And Other Entitlements

The last two chapters of Stephanie Kelton’s The Deficit Myth are focused on the real problems facing our economy and steps we can take to deal with them. These chapters show that thinking along the lines of Modern Monetary Theory is consistent with the goals of progressives, and that MMT can be applied to support working people and our society.

In this post, I look at some of the reviews of the book. I’ll start with this one from the Wall Street Journal by John H. Cochrane. [1] Cochrane begins with a complaint: what is MMT, it’s so confusing. Then he claims he wanted to learn logic and evidence supporting MMT. Maybe a professional economist shouldn’t look for technical descriptions in a book written for the general public. He then spins out a collection of weird stuff (she praises Kennedy for helping unions!) and misreadings (she doesn’t cite peer-reviewed papers, ignoring the footnotes).

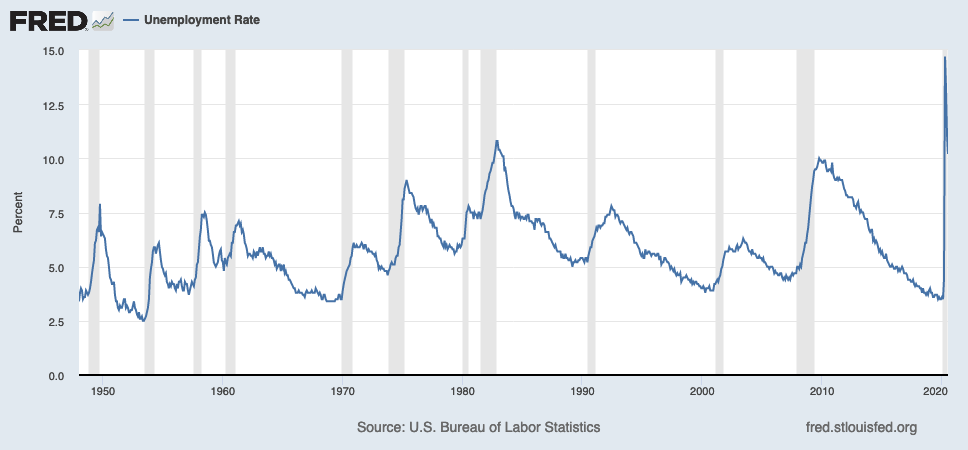

He admits that the government can print money to meet its needs. He understands Kelton’s insistence that the real constraint is inflation. But how will we know if there is slack in the economy or if we’ll get terrible inflation, he asks? He likes the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflationary Rate of Unemployment. Kelton rejects NAIRU on the grounds that there is no such thing. Ignoring her reasoning, he sneers at her conclusion that NAIRU is a “… doctrine that relies on human suffering to fight inflation.” Here’s a chart showing the top-line unemployment rate from FRED:.

The gray bars represent recessions, most of which were caused by the Fed to fight inflation. The result is increased unemployment, which is solid evidence that Kelton is right.

He tries to make actual arguments:

“Taxes are there to create a demand for government currency.” This is a deep truth, which goes back to Adam Smith. Soaking up extra money with fiscal surpluses is, in fact, the ultimate control over inflation. But then arithmetic fails her. To avoid inflation, all the new money must eventually be soaked up in taxes. The new spending, then, is ultimately paid for with those taxes.

Well, not really. That’s why we have a national debt: it’s accounts for the actual wealth created by the government. We can raise or lower it as needed using taxes, all for the rational purpose of managing inflation. [2] There’s much more in the same vein, but that’s the flavor.

Here’s a generally laudatory review from Hans Desplain, a professor of political economy at Nichols College, in the London School of Economics blog. Despain recognizes that this is a book for lay people, and isn’t concerned about Kelton’s failure to address the ontology of money. [3]

Here’s one from the Mises Institute. The writer, Robert P. Murphy, is a senior fellow at the Mises Institute, a group focused on Austrian economics and libertarian political economy. He agrees with much of what Kelton says. His primary objection is this:

… [R]egardless of what happens to the “price level,” monetary inflation transfers real resources away from the private sector and into the hands of political officials.

“Monetary inflation” in this sentence means spending money without regard to tax revenues. Murphy’s concern is the violation of the principle that the private sector should allocate all resources, and any effort by the government to decide what society needs or wants is just bad. Another way to read this is that MMT is agnostic about government action. Kelton advocates forcefully for government action to amke people’s lives better. Murphy is on principle opposed to government spending. This is one of Kelton’s central points. We need to debate the allocation of resources as a society, and we do that through our democratically elected officials.

One final artical, this one by J. W. Mason in The American Prospect. Mason is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the John Jay College at CUNY. Based on his affiliations, he seems to be a progressive.

He points out that MMT is new, and therefore isn’t a polished structure of thought. It’s a “… ramshackle assemblage of parts built at different times for different purposes, tied together with loose solder of association and inference rather than tight bonds of deduction.” He accurately summarizes Kelton’s thesis and her solutions.

Mason disagrees with Kelton’s contention that all money comes from the government. He points out correctly that banks create money, and that Kelton does not address this point. I discussed a paper Kelton wrote on the nature of money here. She argues that money is a debt relationship, a matter of balance sheet entries, and discusses the superiority of this view to other theories. As Kelton says, quoting Randy Wray, “[m]oney is privately created when one party is willing to go into debt and another is willing to hold that debt….” [4]

In footnote 1 here, I briefly discussed the issue of bank-created money in MMT, based on this article by MMT economist Bill Mitchell. Mitchell says that banks do create money, but at the same time they create a liability, so the balance sheets of the bank and the borrower don’t change from the creation of money. When a government creates money it creates a liability on its books, and the consumer gets an asset. As I see it, the difference is that the government can decide to hold the liability forever while banks expect to be repaid promptly, which destroys the money created by the loan. Banks do lose money on loans, leaving the money in circulation, but that’s not supposed to happen. That’s one difference.

The second difference is the the government controls bank lending. It can limit or prevent banks from creating money through regulation of required reserves. Third, obviously the government has to consider bank-created money when addressing inflation. Finally, bank lending does not help in troubled times, when people don’t want to borrow. Right now, for example, personal savings are at a 60-year high, as people who still have jobe pay down debt and put off large purchases.

The ontology of money is way beyond the scope of Kelton’s book, but I do agree that at least bank-created money must be incorporated into the MMT framework more thoroughly. Edited to add this: Scott Fullwiller, an MMT economist at UKMC, commented below saying that MMT already incorporates bank-created money thoroughly. Fullwiller refers us to this post by Brian Romanchuk replying to Mason’s review.

Mason points out that this and other issues he raises don’t detract from the central insights of The Deficit Myth, saying that Kelton’s insights can stand alone and serve as a guide for action. This is a very useful review.

This is just a small sample, but it reveals one crucial thing: some serious people have begun to grapple with the actual arguments made by MMT theorists, and others will ignore the challenge MMT poses to conventional thinking, and defend their prejudices to the bitter ugly end.

=======

[Graphic via Grand Rapids Community Media Center under Creative Commons license-Attribution, No Derivatives]

[1] Here’s the link; it’s behind a paywall, but I got it from my library.

[2] Cochrane’s Wikipedia page has a section titled Main Contributions. It states his research interests, and then offers this assessment, loosely translated as “snicker”:

That is a standard general equilibrium logic, but many financial economists do not view it as a priority and prefer to explain prices without an ultimate reference to choices of households and firms. Similarly, many macroeconomists choose not to worry about asset prices.

In this vein, Cochrane’s work has been to document some empirical patterns and offer some potential explanation….

[3] The ontology of money is a real thing. You could look it up.

[4] Fun question: is bitcoin money? Who is on the opposite side of the balance sheet?

Thanks for the series Ed. It inspired me to read the book, which I enjoyed. It’s nice to consider how to make the world a better place, outside of the daily froth of drama.

For what it’s worth, most of what I knew of macroeconomics before reading this book came from Theories of Political Economy

by James A. Caporaso and David P. Levine. I liked their relatively unvarnished presentation of theories from Marxism to capitalism and the idea that politics and economics form a Venn diagram of how people get what they want from other people.

MMT has always integrated credit money. Wray’s first book in 1990, “Money and Credit in Capitalist Economies,” was 100% about credit money and is one of the classics in the endogenous money literature. In the ‘original’ MMT book, Wray’s “Understanding Modern Money,” all of ch. 5 is about integrating his 1990 book into MMT. Mosler’s first piece, “Soft Currency Economics,” in 1994 integrated state money and credit money. Mosler/Forstater 1998, “A General Framework for the Analysis of Currencies and Commodities,” integrates “state money” and “credit money.” (Both Mosler pieces are on his website.) Wray’s 2004 edited volume, “Credit and State Theories of Money,” integrate both. Tymoigne’s 2016 paper in the Cambridge Journal of Economics, “Government Monetary and Fiscal Operations–Generalizing the Endogenous Money Approach,” integrates yet again state and credit monies. My own articles, “An Endogenous Money Perspective on the Post-Crisis Monetary Policy Debate” (2013) and “Modern Central Bank Operations–The General Principles” (2008/republished in a collected volume in 2017), have in separate years been listed in the Post Keynesian Reading List as being among 4 recommended papers from the entire Post Keynesian canon as representative of the endogenous money/credit money literature. Wray’s book for lay people, “Modern Money Theory,” incorporates credit creation, as does his book for lay people on Minsky (“Why Minsky Matters”). I can literally go on and on and on here. There are dozens and dozens of academic papers and chapters in the MMT literature on credit money, financial regulation, the role of the financial system in economic growth or the crowding out debate and so on. Wray did his PhD under Minsky and especially in the 1990s published 10-20 academic articles on credit money that are among the very, very best in that literature. The MMT textbook from last year by Mitchell/Wray/Watts has some of the best chapters you will find in any textbook on credit money. Overall, to say that MMT hasn’t integrated credit money is the equivalent of saying one hasn’t read much of the MMT literature. Finally, one must understand is that Stephanie’s book is called, The Deficit Myth, so it is about deficits; there was a team of ‘corporate’ editors that were strict about keeping her book from having multiple moving parts. Yes, it’s the best introduction yet to several parts of MMT from a lay perspective (as you explained well here). But it is obviously not a summary of 400+ academic MMT publications and thousands of blog posts, which would have required doubling (at least) the book from 300 to 600 pages. (You might look at Brian Romanchuk’s response to Mason’s review at Bondeconomics.com–he correctly echoes my general sentiment here regarding credit money and MMT since he knows the MMT literature.)

Thanks for taking on Kelton’s book, Ed. It’s a very timely topic and you covered it well.

I’d classify the Austrians as neoliberal. They support having a government powerful enough to enforce restrictive labor laws and to loosen international capital flows–and to join the international organizations that make NL work and enforce their rules. That seems to be rather more government than a libertarian would want.

Good day to all: this continues to be an interesting discussion. One typo noted: Kelton advocates forcefully for government action to amke people’s lives

Ontology of Money: having a hard time making sense of this…a lot of paywalls in the way…I hope it is not like Plato’s thingness: “I can’t find the horseness of the horse.”

Anyway, some really interesting stuff here. Thanks, Ed and contributors.

Regards, Philip

I think economics has been permanently changed as a result of the pandemic. Deficits are no longer the bogeyman. Here’s a piece I wrote a few months ago about the deficit debate, includes a discussion of Kelton and MMT:

https://www.cpexecutive.com/post/the-debt-the-deficit-and-commercial-real-estate

[I clipped this link to remove the tracking parts. Please do that in the future. EMW]

Sorry, I’m not that savvy about links.

Cochrane, a Stanford and Hoover Institute man, does his affiliations proud. His, “But then arithmetic fails her” reference to Stephanie Kelton is a classic faculty lounge put down. It’s not an argument. Its usual purpose is to dismiss the work and priorities of those they disagree with.

Murphy’s objection ignores capital’s principal concerns about inflation: it lowers financial asset values and, at certain levels, makes it easier for debtors to pay debts. That’s anathema to capital, for whom debt is a hierarchical power relationship that should be permanent. That raises the general concern of why study economics, to what ends is that put?

For Kelton, it seems to be to do no harm and to make government work for the most people. Her work helps take the blinders off and let people see how “economic laws” are often political choices, which can be altered to pursue different priorities.

Her critics often see people as statistics, objects to be herded and directed toward the goal of increasing capital’s wealth. The devisers of Homo economicus fit that bill. For them, economics is a way to corral government. They aim to keep it from competing with capital, to geld it ability to rein in their excesses or force them to internalize the costs of the harm they do to make money.

Well, EoH, that last paragraph was about 25% of my next post, so, thanks?

Always glad to help. Call any time. :>)

I would appreciate if someone could explain to me how the US debt could be financed if demand for US Treasuries dried up? Is this discussed in the book? Am I to believe it is irrelevant? Doesn’t it require faith in the currency to fund debt? If investors began to feel that one might not be paid back for their investments, wouldn’t that make it far more difficult to raise capital?

I freely admit I do not understand the “Fed’s balance sheet” and how it is balanced (as the Fed’s balance sheet is often discussed). I feel I understand how the public debt is financed much better.

Thank you for this discussion.

Chris, at the top of this page you will find other posts in this series. Please read the first three, at least. They set up the context and offer a short version of the basic ideas of MMT. I hope they will inspire you to read Kelton’s book.

Most people believe as you do that the deficit and the national debt are problems. They can be if they lead to inflation. Otherwise they aren’t. The discussion by Njrun lays out the conventional view which is totally wrong,. It’s wrong in a bad way, because it teaches people we have to rely on rich people to operate our economy. We don’t. . MMT offers a completely different view, one that I think is accurate.

I’m putting up another post on this to close out the series. Please feel free to ask further questions.

Chris:

The US relies on investor demand for Treasuries to fund the deficit. That much is true. You’re probably now thinking that makes deficit spending a risky proposition.

The historical way economists viewed this was that the higher the deficit, the greater the supply of money, which would drive up interest rates because the supply of bonds would eventually become greater than the demand.

But that hasn’t happened. As the deficit has grown and the supply of Treasuries has gone up, rates have gone down. Why? A lot of reasons, including some probably not understood. For one thing, the supply of investment capital has gone up. There’s a lot of capital from institutions, pension funds, sovereign funds, mutual funds, billionaires and so on that needs something to invest in. The total amount of that capital is way more than it was 10 or 20 years ago.

Given that, U.S. government bonds look attractive. They are seen as the safest investment on earth. If you think our economy is bad, the rest of the world has problems as well, many that are worse. Plus, as low as Treasury rates are, the return is still better than the return offered on bonds of most other sovereign and wealthy western nations that would also be seen as safe bets for repayment.

I discuss this a bit in the article I linked to in my comment above.

Bottom line is that the deficit in the U.S. is not seen by economists in as apocalyptic terms as it was in past decades. Interest payments are so low that the borrowing isn’t as much of a burden as it was in the past. The question is whether deficits are a problem at all, or if there is some point at which they will prove to be harmful.

The MMT view is that deficits mean nothing, and most economists wouldn’t go that far. Some like Jason Furman, a moderate who was an Obama appointee, note that other countries have had bad experiences with rising debt. I think the discussion has moved a lot in recent years, and that will help the Biden administration implement some bold policies, if the election goes well.

You are wrong. The US does not depend on investor demand. I discussed this issue in detail here: https://www.emptywheel.net/2020/06/16/debunking-the-deficit-myth/

Kelton explains it in more detail in her book and there is more in her other work and in the work of other MMT theorists.

For evidence, look at the holder of the US debt. The Fed has bought vast amounts and holds it on its books. It can do so indefinitely. Your view of this matter is based on conventional neoclassical/noeliberal theory. That theory is based entirely on commodity money. We have a fiat currency and have been completely off commodity money for decades. Perpetuating your antique opinion makes it hard for people to understand the way things actually work.

Please read my posts and the original literature before you comment again.

Interesting response. I can’t comment unless I pay fealty to your work? Dude, you’re smart, but if you found my innocuous comment offensive, you must be angry an awful lot of the time.

Yes, my “antique opinion” comment is based on how the market has traditionally worked. Yes, the fed can buy all the Treasuries, which makes the investor demand equation moot. But only if the Fed chooses to do so. There’s no guarantee that any Fed will do that. Traditionally the Fed has tried to keep the balance sheet low.

We’ve discovered the Fed can run a large balance sheet and not hurt the economy, but it remains to be seen how much and how long that holds. That’s an observation, not an opinion.

“How the market has traditionally worked” usually means “how everyone was taught that it worked, without regard to facts”.

Ed didn’t find your comment “offensive.” He found it to be an incorrect description of MMT and an outdated view of political economy.

How the market traditionally “works” is not the same as how it has been traditionally described. MMT’s view is that the constraints on a currency-issuing government’s spending are inflation and real resources. If you want to refute such arguments, it would seem necessary to read up on them. If you think that requires you to “pay fealty” to them, you’ll find other sites more congenial.

I wasn’t describing how MMT works, wasn’t refuting anything, I was answering someone’s question, which as far as I could tell wasn’t about MMT. People are free to answer differently. Free to disagree. I don’t see how what I said, which was polite, created so much hostility. This place is weird.

Your position is that in a post about MMT, you explained an element of political economy – the impact of deficits – by ignoring it. When the post’s author pointed that out, you reacted badly by saying that considering MMT would require that you “pay fealty” to the subject of the blog post. That’s what’s weird.

It’s not as if you aren’t familiar with the literature. Your article, which you cite, above, describes MMT – through the lens of its position on deficits – as “an interesting but quirky academic theory,” with “more permissive views on debt….viewing it in descriptive rather than qualitative terms.”

But other than as a potential explanation for why, to paraphrase Dick Cheney, deficits don’t matter, you seem not to have much use for it, except when MMT’s position intersects with Republican opportunism. That is, their temporary lack of concern about deficits, owing to their having fed at the deficit-driven trough created by their 2017 tax cut. (Pace, Cheney.) Empirically, have you noticed that that lack of concern resurfaces immediately when a Democrat enters the White House. Never mind.

Earl, when I wrote the piece above, I spoke to a number of economists, not just the ones that are quoted. The quirky part is how MMT is viewed in the field, not my opinion. A common comment from people in the field is that they have a hard time understanding exactly what MMT is.

The piece is intended to reflect a spectrum of views. I’m not an advocate, I’m not on anyone’s side.

I’m raising the idea that deficit is going to be less important in policy decisions going forward. I think that means more spending on things such as employment and infrastructure, and the deficit scold view that we can’t afford to spend has less weight.

I don’t give a crap about labels, and I’m not fighting a side in this, but what I’m describing is that economic policy thinking is shifting to something more favorable to MMT’s goals.

1. MMT prescribes no specific policy goals. It describes monetary operations as they take place in the real world, and draws various conclusions directly from that factual description. MMT economists are always careful to hold out their policy recommendations as distinct from MMT, though policy opinions are often conflated—as you have done in your article—with the underlying body of knowledge. It’s not usually clear whether this is done out of ignorance, or of a desire to perpetuate the status quo.

2. Your piece is not apparently based on any deep (or even shallow) understanding of MMT, which makes it little more than a puff piece steeped in bothsiderism. If you hold yourself out as an expert perhaps you should have disclosed your inadequate knowledge of MMT somewhere in the article—or, preferably, learned something about it. Merely saying ‘some folks think MMT is a little wacky but maybe it’s getting less wacky even though I couldn’t find anyone who thought that way” isn’t that helpful to anyone, especially your readership.

3. With the exception of oil and gas, I don’t think there’s a segment more dependent on special tax breaks—and the ability to recombine these tax breaks and resell them to the wealthy—than CRE; the objective seems to be mainly to create sinecures for the GPs. Interestingly, if CRE embraced the JG their own industry would likely perform better, but they don’t get it. You should be helping them see.

You are free to be wrong as often as you like, and I can see you like it a lot. in the future I won’t bother replying.

You are allowed to be stupidly irritating once. Then you are banned.

Stupidly irritating?

I like being wrong? Wow.

I’m a well known and well respected person in the market in which I work. I’m not an economist, but I’m an active member of a major economists organization. I know high-profile economists. One thing I can say about the ones I know is that are unfailingly civil.

Well, it would not be the first time that I landed in hot water around here, if I were to point out that reading this thread put me in mind — of all things! — of a subfield of archeology called archeoastronomy. When things change, it can be hard for everyone to shift at the same time, and often the vocabulary for new events and ideas will lag.

There are ancient stories about Heracles tossing a snake/python out of heaven, and tales across the world of ‘dragons/snakes dethroned’. These stories cluster around events that occurred in roughly 2,700 BCE.

Around 2,700 BCE, the star Thuban, in the constellation of Draco, was the pole star. It had been the pole star for millennia, and the zodiac and constellations of that era were shaped by an assumption that Thuban would always, and forever, mark the ‘pole of heaven’ atop the night skies, where Draco guarded the Golden Apples of the Hesperides.

However, the earth being more egg shaped than round, it wobbles. Over many centuries, the wobble results in precession: the pole star shifts. People in 2,700 BCE didn’t fully understand this factor; famines, disasters, and unexplained circumstances were all attributed to the unexpected and disturbing fact that they could see with their own eyes: ‘Heracles tossed The Serpent out of Heaven’. Thuban was no longer the pole star; people were confused and had to figure out a ‘new story’ to adapt to new circumstances.

My sense is that Njrun is noting a shift of polarity, and is still developing the full vocabulary (and concepts) to discuss this shift. Reading his/her article, I’d say Njrun is someone coming to MMT and trying to describe it to an audience that is going to have a **really** hard time getting their heads around some MMT concepts. In my observation, people who invest in commercial real estate are convinced that deficits matter. (Indeed, for one guy I know, deficits are a central pillar of this thoughts on all things capitalist and economic.). I assume that Njrun had his/her work cut out trying to explain MMT to an audience of real estate investors.

EWheelies have been discussing the decline of neoliberalism, and the ascendance of MMT, in one form or another, for a number of years.

This blog probably has more vocabulary, more familiarity, more conceptual comfort with MMT among the extraordinary group of readers than the audience that Njrun was targeting. Ed is moving a discussion of new economic models along, and it’s important.

I respect Njrun’s efforts to engage with MMT, and explain it to an audience that would be wary, if not downright hostile — people who are *convinced* that deficits matter, and for whom, ‘Deficits = Bad’ is an article of faith.

I am not at all surprised by Njrun’s report that economists referred to MMT as ‘quirky’, which I interpret as, “Not too threatening to our existing economic/political assumptions.” .

In my mind, people who dismiss MMT as ‘quirky’ are akin to people who worshipped Thuban atop the pole of heaven, and floundered, unable to adapt, as the pole star shifted. (I can almost hear them, ‘Twelve Labors…? Who does this Heracles guy think he is?!’)

I also respect the amount of time and energy that Ed puts into writing these posts (actually, frankly, it’s hard to get my head around).

If, as I suspect, economic theory is shifting, and it is complicated stuff, some misunderstandings are to be expected. Trying to shift understandings about our assumptions of the way the world works, and why, takes energy and time.

I hope that any hard feelings will dissipate shortly, as this whole topic is far too important to run amuck on shards of ill-will. I hope putting this in a perspective remote in time, but profoundly disorienting to the people who lived through it, is not too off-topic for the thread.

It’s probably something like in physics, having to adjust to relativity and not having ‘ether’ around as a concept any more, and then having to deal with quantum mechanics on top of that.

If you’re well acquainted with the dismal science, then you also know that no economist or theory has a lock on the field. You also know that theory is just that — not set in stone and subject to revision as assumptions are proven flawed. Discussion about MMT addresses a different set of assumptions which you are not comfortable with based on your comments. Your discomfort doesn’t mean the theory here is wrong, only that it doesn’t match the theories on which you have built and invested your personal framework of understanding.

How you handle that discomfort is your responsibility. We’re not here to make you feel at ease. We’re also not here to be lectured by someone who’s not comfortable with the conflicts between theories and worldviews.

Specifically, we’re not going to tolerate tone policing when you’re struggling with theory and should spend more time wrestling with it offline.

Nrun – Did you know Donald J. Trump is a stable genius, unfailingly addressed as “Sir” by all, far and wide? He has a very good brain, the best words, and he even gets two scoops of ice cream.

According to him, anyway.

I have been following this site for a few years now reading and learning. Thank you all. Thank you, Ed, for do this series. I have read Stephanie Kelton’s book and was impressed. I would like to take the reference to the Mises Institute as an opportunity to ask you and the collective wisdom for a reference to books or articles that provide a good critique of the Austrian school (Hayek and company). Thanks in advance for any help. [If this is in appropriate for the comments section and you decide not to post it, I understand.]

Pre-Hayek Austrians introduced some concepts that have become commonly accepted, such as the idea that price can be determined subjectively based on the utility to the buyer. However, starting with von Mises in the 20th century Austrian beliefs changed completely.

My suggestion would be to view this brief video (https: //www.youtube.com/watch?v=SLfnpwHu4Hw) and read through this (https: //www.econlib.org/library/Enc/AustrianSchoolofEconomics.html) to get an idea of the basic beliefs. They’ll probably sound reasonable to you. (I broke the links intentionally)

Then read “Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism” by Quinn Slobodian. It provides historical context about the development of Austrian economics that I found valuable.

If you then review the previous materials, you’ll see them (and today’s economic reality) in a different light.

Thank you , Bruce. I have a basic understanding of their positions. What I am looking for is more current critiques of the Austrian school. But I will follow up on your suggestions. Thank you for taking the time to respond.

Thanks, Bruce. I read Keynes Hayek: The Clash that Defined Modern Economics, and a big chunk of The Road To Serfdom. That was enough to persuade me to avoid the Austrians. The book was a good history, showing how Hayek got his start after WWII.

Just wanted to note the changes happening to our Northern cousins. Freeland (what a great name, eh?) just replaced the Trumpie like economic minister for Trudeau. She sounds like a great choice and echoes, for me at least, all this MMF discussion, sans the discord above.