MMT On Inflation

Posts in this series

The Deficit Myth By Stephanie Kelton: Introduction And Index

Debunking The Deficit Myth

The second chapter of Stephanie Kelton’s The Deficit Myth deals with inflation. In Chapter 1, Kelton explains that the deficit is not a constraint on government spending. Instead, inflation is the important constraint. A deficit does not prove that the federal government is overspending. Only an increase in inflation proves Congress is overspending. Kelton says Congress shouldn’t tax and spend so as to deliver a balanced budget. Congress should spend and tax so as to deliver a balanced economy, one that serves all of us. She says that historically we have not done this, that we have chosen to focus of deficits and in so doing our economy has not served us well.

Definition and Description of Inflation

Inflation means a continuous rise in the price level. A bit of inflation is considered harmless and even something economists like to see in a healthy, growing economy. But if prices start rising faster than most people’s incomes, it means a widespread loss of purchasing power. Left unchecked, this would mean a decline in society’s real standard of living. In extreme cases, prices can even spiral out of control, gripping a country in hyperinflation. P. 44.

The danger of eroding incomes explains why everybody worries about inflation, and explains why politicians can use the threat of inflation to terrorize voters. It works, even though the problem for more than a decade hasn’t been too much inflation, it’s been too little. Ever since the Great Crash inflation has been less than 2% annually despite efforts of the Fed.

Kelton says that economists think of inflation as either cost-push or demand-pull. Demand-pull inflation occurs when consumer spending rises faster than the economy can produce goods and services. That hasn’t been a problem for a long time. Cost-push inflation can arise from disasters, which reduce the supply of something; from pricing power, as in the case of Big Pharma with its patents and trade secrets; or from workers gaining market power and demanding higher wages which businesses pass on to consumers. That last one is the only fear mainstream economists suffer, as far as I can tell.

The dominant theory of inflation stems from Milton Friedman’s monetarism:

According to Friedman, “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” What he meant was that too much money is the culprit in any inflationary episode. If prices weren’t stable, it was because the central bank was trying to force the economy to create too many jobs by allowing the money supply to increase too rapidly.

The early neoliberal Friedman insisted that the Fed must never interfere with the workings of the market. Specifically, the Fed should not try to reduce unemployment below a certain level, which came to be called NAIRU, the non-accelerating inflationary rate of unemployment. Friedman thought there had to be some minimum level of unemployment in the economy. [1] The Fed bought into this view, as did politicians of all stripes. They all agreed that to keep prices stable, the US has to accept a certain level of unwanted unemployment. And to be on the safe side, maybe a bit higher level of unemployment. In practice, Congress dumped the problems of inflation and unemployment on the Fed.

But problems arose. The NAIRU isn’t visible or measurable. It can only be seen in retrospect. And now we are pretty sure there isn’t a clear relationship between inflation and unemployment, as the Fed assumed. [2] The Fed Chair, Jerome Powell, freely admitted to Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez that the Fed has been wrong about NAIRU, but defended its use on the grounds that “We need to have some sense of whether unemployment is high, low or just right.” P. 53.

2. The Problem of Unemployment

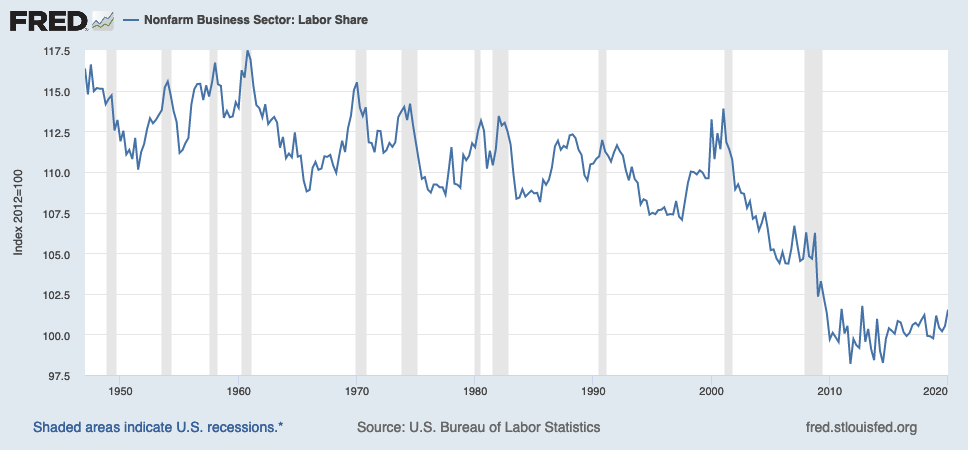

It turns out that the Fed used the purported correlation between inflation and unemployment as its primary tool for controlling inflation, ignoring all other causes of inflation. When the economy heated up and unemployment dropped, workers gained market power, and their share of national income increased. That led the Fed to raise interest rates leading to a tightening of the economy and usually a recession, as the following chart shows.

Gray bars indicate recessions.

Kelton calls this a “human sacrifice”, forcing some people out of the workforce when they want to work and can be productive. She thinks we are asking too much of the Fed. It can’t spend money into the system; only Congress can do that. All the Fed can do is change the cost of borrowing. If unemployment is too high, the Fed can make borrowing cheaper, but it can’t force anyone to borrow. Usually when unemployment is high, no one wants to borrow. I note that this was what happened after the Great Crash. The Fed cut interest rates to zero and lowered bank reserve requirements, hoping to increase money going into the economy. It didn’t work.

3. The Job Guarantee

Kelton argues that a better way to deal with unemployment is a job guarantee. Every person who wants to work should be able to get a decent job with decent pay and decent benefits. If the private sector won’t provide those jobs, the government should. [3] Kelton discusses this idea and its foundations.

It would probably be impossible for Congress to monitor the economy closely enough to manage full employment by tweaking taxes and spending. A job guarantee would act as a safety-valve and an automatic stabilizer for the economy and help solve this problem, leaving the Fed free to focus on inflation. If the private sector needs all the workers it can find them. If not, the government hires people to do jobs that need doing. There is plenty of work that needs doing, and, as Kelton pointed out elsewhere, we can always use more flowers in our parks and boulevards.

4. Preventing Inflation

So how should Congress budget knowing that the only effective constraint on spending is inflation? What would change? The way Congress currently works is that every bill that calls for expenditures gets a score from the Congressional Budget Office that assesses the impact of the expenditure on the deficit over a ten-year period. If inflation were the constraint, then the CBO would offer a score based on the probable impact of the expenditure on inflation. If the economy is, as now, operating well below its capacity for producing goods and services, the possibility of inflation would be low.

If the economy is close to capacity, either as a whole or in part related to the area of expenditures, then Congress has to make hard calls. How important is the expenditure? Can we create “fiscal space” for the expenditure with taxes? For example, in the case of the entire economy humming along, a general income tax hike would take money out of most people’s hands so they would not be buying as much, leaving room for the government to buy more. If there is a bottleneck, a more focused tax or some other step might be necessary.

Conclusion

MMT recognizes that inflation is a crucial problem. It shows how it arises and how we should protect ourselves from it.

=====

[Graphic via Grand Rapids Community Media Center under Creative Commons license-Attribution, No Derivatives]

[1] Marx said that the reserve army of labour is a necessary part of capitalism. Hmmm.

[2] This relationship is embodied in the Philips Curve. I discuss it here.

[3] Other economists favor a universal basic income. Both have the added benefit of freeing workers from abusive or irritating employers. Your family won’t starve if you walk out on a bad situation.

Thanks for taking this book up now, Ed. I’ve been immersed in MMT for about 3 years and it finally seems to be getting some attention.

Before someone brings up Zimbabwe, Weimar, and the rest I think it’s worth restating Adam Eran’s remark (on your previous post) about hyperinflation, which has never been caused by government overspending.

It sounds like NAIRU was accepted without any peer reviewed studies backing its hypothesis. Is this a common theme in applying an economics education from a particular school towards policy decisions? “My grand puba thought this, therefore it is?”

Most current thinking in economics tends to favor business because that’s who commonly pays for studies, chairs, buildings, etc. It’s not a conspiracy as much as it is a “neoliberal thought collective” as Philip Mirowski uses the term.

The rise of neoliberal thought, as told by Quinn Slobodian in “Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism” is highly revealing.

NAIRU is based on the Phillips Curve, which in turn is based on work done by William Phillips. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillips_curve As I note in my discussion (linked at FN 2 above), it doesn’t seem to work any more, if it ever did. Nevertheless, it’s one of Mankiw’s Ten Things Economists Agree About. https://newworldeconomics.com/greg-mankiws-ten-principles/

I think the problem is that once an idea gets put into an economics textbook, people assume it’s true. There was some empirical evidence for the Phillips Curve, and economists ran with it. Now that it’s being questioned, it has many defenders, including the Fed, which incorporates it into the models.

This is a general problem, which gives rise to the idea that science proceeds one funeral at a time. The textbook problem was identified by Thomas Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. I devoted a good bit of effort to understanding Kuhn in the context of economics. Here’s a summary post with lots of links. https://www.emptywheel.net/2015/06/28/kuhn-and-economics-a-summary/

There’s some debate about JG vs. UBI but there’s a place for both.

Step 1 is to implement universal healthcare that includes vision, dental, hearing, behavioral/psychological, long-term care, physical therapy, etc. So everyone receives the same level of benefits. If you have more money, pay more out-of-pocket if you want to.

With that in place, a subsistence-level UBI would replace (roughly) Medicaid and disability programs. If you’re disabled, or want to stay home and raise your kids, you get paid to stay alive. Or if you’re an entrepreneur and want to put 100% of your time into a startup, or write a book, or sit in a tree and learn to play the flute.

A higher-paying JG would replace unemployment. It pays more (a living minimum wage) because society would get value out of you every day. I fractured my ankle last summer because of a badly-maintained public planting strip (coupled with stupidity) and Medicare pumped over $5000 into physicians, exams, therapy, and so on to fix it. Market failures such as that abound.

I support UBI and JG, and universal healthcare, and the right to shelter. Come to think of it, I am even in favor of eliminating borders. Yes, really I am.

But what does any of that have to do with MMT? The Fed *is* doing MMT now – buying almost every US Treasury bill/bond it can find. It’s not a simple thing this buying bonds and shifting prices in huge money markets – $10T traded daily – and trying to figure out who is leveraged to the hilt – and trying to figure out how to divert the money to useful causes – and not to the stock markets and the most recent billionaire’s umpteenth mansion in the latest fashionable tax haven.

MMT is not really about money. It’s a political anthem. I hated it when Friedman covered his political siren songs with the label “monetarism”. But I’m afraid that MMT is of the same ilk. We do run deficits. That’s fine, that’s as it should be. And we also print money and that’s fine and as it should be.

The argument is really about who gets to spend the money. The really big spending is the military-industrial complex. A nice old-fashioned word. That plus energy mining subsidies and industrial agriculture subsidies is what keeps the red states afloat. That’s the real budget deficit. No wonder they think elections are war. Without government spending they are yesterday’s cold toast.

Sorry, MMT really is about money. Nothing more. It has no political agenda.

But you’re correct when you say the Fed is using their knowledge of how deficits work (as described accurately by MMT) to benefit the military, energy, finance, large corporations. It’s patently obvious that the GOP has understood for decades how fiat money works (whether you call it MMT, or chartalism, or whatever)–Dick Cheney famously pointed out to Paul O’Neill “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter”. They gin up fear of deficits but spend the money anyway, for items on the GOP’s political agenda.

Polls show most Americans believe in taking care of other people but political leadership has them convinced it’ll be too expensive. It’s that false fear of deficits that Stephanie Kelton’s book is attempting to dispel.

“false fear of deficits” – completely agree.

“MMT is really about money” – no, MMT is about managing government debt. What the government actually buys with it has nothing to do with money – or the Fed, for that matter.

IMO, both MMT and monetarism are too simplistic to argue about. The real argument is about spending, what to spend it on.

I agree with just about everything said here, vis-a-vis UBI and JG. I would add that colleges and universities, contrary to the RWNJs, are generally conservative as it applies to economics. I remember well, being scolded while an Econ TA in the early 80’s, for stating the obvious that “reaganomics “ and the Laffer Curve were empirically disingenuous and simply slogans for redistribution from the poor to the rich.

To me, the problem Alan K. raises is the difference between two poles of thinking: normative and empirical. To me, MMT is an empirical answer to a simple question: how does money work in a nation sovereign in its currency as compared to one that is less than fully sovereign, or totally not sovereign. It seeks to answer basic questions about the exact way money is generated and used in each.

That should be contrasted with normative thinking about the economy: what should it do?

The link comes when we decide what we want to do as a society. Then we can use the insights of MMT to decide how best to accomplish our ends.

Kelton argues that a nation should pursue a balanced economy, one that works for everyone. Neoliberals disagree. They say the society doesn’t get to choose, that the “market”, an undefined term, should be used to decide what to do and how to do it.

Not an economist, but this theory fits in with actually funding infrastructure, rebuilding highways, bridges, airports, ports, water pipelines, etc. In other words people get employed to build and improve upon this infrastructure. It might even be possible to reopen the US steel industry to provide the necessary steel (more employment) for these projects. Anything is possible if the deficit is not a constraint.

With the caveat that inflation is still a constraint, then yes.

Things the GOPer Power Elite Don’t Want You to Know:

#1. Infrastructure pays you back. Handsomely.

We should have a standing WPA constantly bidding for workers to upgrade our infrastructure. And if we were really smart, a politically independent oversight body to set its priorities.

The GOP doesn’t like infrastructure because its donors don’t like public spending, which wastes money producing assets that don’t provide private benefits (read: revenue streams) to those donors. They prefer public-private partnerships, where the public is essentially funding the creation of a privately-owned asset/revenue stream.

The WPA was much more than mere infrastructure, and the JG should include a variety of jobs as wide as the WPA did. It helped support Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Jackson Pollock, John Cheever, Arthur Miller, Orson Welles, John Houseman, Elia Kazan, and many more. It interviewed thousands of ex-slaves, and recorded folk music all over the country.

The HUAC complained bitterly about the supposed pro-communist attitudes of some of the artists and most of the programs lasted only about 4 years, from 1935-1939. Plus ça change…

One question mark for me relates to carbon taxes and how policy would account for inflation.

We obviously need a massive carbon tax, either directly or via some kind of more complicated system. But to be effective, it ought to hit hard and fast — people will move a lot more slowly and haphazardly if it is slowly phased in. The cost push effect has to be significant.

Which in the short run may have a significant inflationary effect. The transition to cheap non-carbon energy may well be a major dampener on inflation down the road, but in the short term rising transportation, manufacturing, heating and cooling costs will probably ripple through the economy in unpredictable ways.

I realize there are worthwhile proposals to offset the effects of the taxes themselves — offering a per capita refund on taxes collected, for example, which would reward people who don’t drive 1,000 miles a week.

But that’s partially a separate issue from the inflationary potential of carbon taxes. The reality is that there is a fair amount of uncertainty how the economy will react.

Which is not an argument against some kind of major carbon tax. We absolutely need one. But we also need to take this into account and think about how to limit the harm it might do in the near term. Funding a counterinflationary national healthcare plan with carbon taxes may be higher priority than a simple tax rebate, for example.

In the context of the four purposes of taxation, the carbon tax is to discourage the burning of carbon and the poisoning of the atmosphere. The design of a carbon tax is the next problem. The good news is that there isn’t any connection between the money raised by the tax and the efforts to ameliorate the problems it will create. We have the fiscal space to fix it as we want to, but I’ll leave the design to others.

The idea of using tax policy as a spur to business conduct should seem routine to neoliberals. I think they object when it’s used to penalize investment rather than to encourage it, and when it’s used to promote any ends but those of big capital. But I think that’s also an argument of convenience, because they’re not consistent.

Neoliberals claim, for example, that large tax cuts spur investments. They don’t. They encourage payouts to investors, because lower taxes cut the cost of taking money out of a business. (Given the surprisingly large percentage of the economy owned by private equity, that should be cause for systemic concern.) I think the record’s clear that businesses invest more during periods of high taxation. They are a deductible expense, which is worth more at, say, a 60% tax rate than a 15% tax rate.

Higher, directed taxes also encourage systematic investment patterns, because a profitable business needs to keep thinking of tax shielded uses for its profits, lest they be taxed in a later year.

During 40+ years in tech, I’ve seen many projects being mischaracterized to capture tax benefits. And I haven’t seen any projects undertaken solely due to the tax benefits.

On the other hand, large-scale real estate development, with its built-in cycles of boom and bust, exists almost solely because of tax benefits. An overwhelming majority of development projects probably shouldn’t be undertaken, but the tax benefits (and the ability to package and resell those benefits) enable them nonetheless.

So, as you can imagine, I don’t see the real-world benefits to this type of encouragement.

If there are customers who need it, the project (whether software or condos) will be funded. The government shouldn’t be involved.

Take that money (heh) and spend it directly on real R&D. There will never be enough top scientists to cause inflation.

The fact that you’re in favor of a market-based solution (a carbon tax) shows how thoroughly neoliberal thought has dominated the discussion. Neoliberals like markets because they can be manipulated.

Mandating electric vehicles, as some European countries have, would reduce carbon pollution dramatically, without needing a complex market solution.

“Congress should spend and tax so as to deliver a balanced economy, one that serves all of us. “

Congress serves the donor class as antebellum protected same.

Money = Speech

Dred Scott = 0

Never mind how much money we waste in systemic servitude (money wasted) to an energy business model which we are as dependent as slaveowner was on human labor…

We the people?

More perfect Union?

Enlighten is elusive for the brutally conditioned who will expend no energy to think?

Just respond to stressor like pavlov’s dog.

They have done it again..

Figure out folks.

I’m certain George Washington would call bullshit on the protection of another Kings monopoly as he told King George and his pandering money addicts…

Go “F” yourself…

“Go “F” yourself…”

Who are you talking to?

Interesting discussion. Thank you.

Followed that Kuhn link from 2015 you posed above, Ed.

There is a reason the Social Sciences are called the Dismal Sciences.

Suggestion for the next book discussion: Katharina Pistor. 2019. The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality. Pistor, an expert on comparative law, is on the Columbia Law faculty, and writes about money, finance, property rights, and corporate governance. A review is here.

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2019/09/26/book-review-the-code-of-capital-how-the-law-creates-wealth-and-inequality-by-katharina-pistor/