Debunking The Deficit Myth

Posts in this series

The Deficit Myth By Stephanie Kelton: Introduction And Index

The first chapter of Stephanie Kelton’s book The Deficit Myth takes up the biggest myth about federal government finances, the idea that federal budget deficits are a problem in themselves. The deficit myth is rooted in the idea that the federal government budget should work just like a household budget. A family can’t spend more than its income will support. The family has income, and may be able to borrow money, and the sum of these sets the limit on household spending. Those who propagate the deficit myth say government expenditures should be constrained by the government’s ability to tax and borrow. First the government has to find the money, either through taxes or borrowings, and only once it has found the money can it spend. The way things actually work is different.

In the real world, it goes like this. Congress votes to direct an expenditure and authorize payment. An agency carries out that direction. The Treasury instructs the Fed to pay a vendor. The Fed makes the payment by crediting the bank account of the vendor. That’s all that happens. It turns out that the real myth is that the Treasury had to find the money before the Fed would credit the vendor. That’s because the federal government holds the monopoly on creating money. U.S. Constitution Art. 1, §§8, 10. In practice this power is given to the Treasury, which mints coins, and to the Fed, which creates dollars. [1]

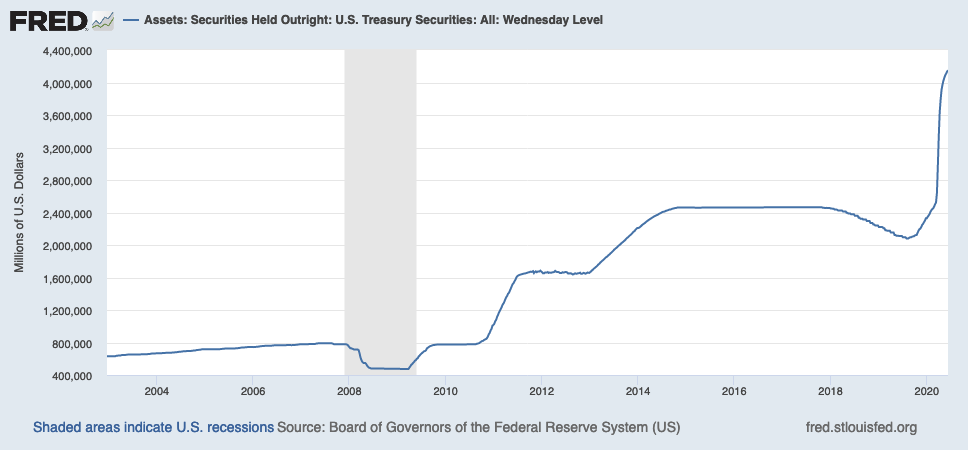

It also turns out that for the most part, the Treasury does cover the expenditure by taxing or borrowing, but because the government is an issuer of dollars, it isn’t necessary. [2] In the last few months, the Treasury has been selling securities and the Fed has been buying about 70% of them. Here’s a chart from FRED showing Fed holdings Fed holdings of treasury securities. The Fed may or may not sell those securities to third parties. If it doesn’t, they will be held to maturity and remitted as a dividend to the Treasury.

The recognition that spending comes first, and finding the money comes second is one of the fundamental ideas of MMT. Kelton describes her meeting with Warren Mosler who introduced her to these ideas; the stories are amusing and instructive. I particularly like this part:

[Mosler] began by referring to the US dollar as “a simple public monopoly.” Since the US government is the sole source of dollars, it was silly to think of Uncle Sam as needing to get dollars from the rest of us. Obviously, the issuer of the dollar can have all the dollars it could possibly want. “The government doesn’t want dollars,” Mosler explained. “It wants something else.”

“What does it want?” I asked.

“It wants to provision itself,” he replied. “The tax isn’t there to raise money. It’s there to get people working and producing things for the government.” Pp. 24-5.

Put a slightly different way, people accept the government’s money in exchange for goods and services because the government’s money is the only way to pay taxes imposed by the government. Kelton says she found this hard to accept. She spent a long time researching and thinking about it, and eventually wrote her first published peer-reviewed paper on the nature of money. [3]

The monopoly status makes governments the issuers of money, and everyone else is a user. That fundamental difference means that governments have different financial constraints than households, and that it certainly isn’t constrained by its ability to tax and borrow. Kelton offers several interesting and helpful analogies that can help people grasp the Copernican Revolution that this insight entails.

Once we understand that government doesn’t require tax receipts or borrowings to finance its operations, the immediate question become why bother taxing and borrowing at all. Kelton offers four reasons for taxation.

1. Taxation insures that people will accept the government’s money in exchange for goods and services purchased by the government.

2. Taxes can be used to protect against inflation by reducing the amount of money people have to spend.

3. Taxes are a great tool for reducing wealth inequality.

4. Taxes can be used to encourage or deter behaviors society wants to control. [4]

She explains borrowing this way: government offers people a different kind of money, a kind that bears interest. She says people can exchange their non-interest-bearing dollars for interest bearing dollars if they wish to. “… US Treasuries are just interest-bearing dollars.” P. 36. Let’s call the non-interest-bearing dollars “green dollars”, and the interest-bearing ones “yellow dollars”.

When the government spends more than it taxes away from us, we say that the government has run a fiscal deficit. That deficit increases the supply of green dollars. For more than a hundred years, the government has chosen to sell US Treasuries in an amount equal to its deficit spending. So, if the government spends $5 trillion but only taxes $4 trillion away, it will sell $1 trillion worth of US Treasuries. What we call government borrowing is nothing more than Uncle Sam allowing people to transform green dollars into interest-bearing yellow dollars. P. 36-7.

It might seem that there are no constraints, but that is not so. Congress has created some legislative constraints on its behavior, including PAYGO, the Byrd Rule, and the debt ceiling, but these can be waived, and always are if a majority of Congress really want to do something. They also serve as a useful way of lying to progressives demanding public spending on not-rich people, like Medicare For All. We have to pay for it under our PAYGO rules, they say, while waiving PAYGO for military spending (my language is harsher than Kelton’s).

The real constraints are the availability of productive resources and inflation. The correct question is not “where can we find the money”, but “will this expenditure cause unacceptable levels of inflation” and “do we have the real resources we need to do this” and “is this something we really want to do. As Kelton puts it, if we have the votes, we have the money.

In my next post, I will examine some of these points in more detail. Please feel free to ask questions or request elaboration in the comments.

=====

[Graphic via Grand Rapids Community Media Center under Creative Commons license-Attribution, No Derivatives]

[1] Art. 1, §8 authorizes the federal government to create money; §10 prohibits the states from issuing money. That leaves open, for now, the possibility that private entities can issue money. Banks and from time to time other private entities play a role in the creation of money, but I do not see a discussion of this in the book.

For those interested, here’s a discussion of the MMT view from Bill Mitchell. I may take this up in a later post. In the meantime, note that every creation of money by a bank loan is matched by a related asset. Thus, bank creation of money does not increase total financial wealth. In MMT theory this is called horizontal money. It is contrasted with vertical money representing the excess of government expenditures over total tax receipts, which does increase financial wealth. Here’s a discussion of this point.

[2] There are, of course, constraints on government spending, especially inflation and resource availability. We’ll get to that in a later post.

[3] Kelton cites the paper in a footnote: The Role Of The State And The Hierarchy Of Money.

[4] Compare this list to the list prepared by Beardsley Ruml, President of the New York Fed, in 1946.

Do US treasuries (or govt. bonds more generally) serve any purpose other than as a gift to rich people?

Not at the moment. Interest rates are so low that the real interest rates on 10 year treasuries actually went negative briefly.

Yes. Treasuries are commonly used in a wide variety of intra-bank lending, swaps, repurchase and reverse repurchase agreements, and other secured transactions. The Fed uses treasuries in its open-market transactions, which are used to control interest rates.That’s why the Fed has a relatively stable number of these securities through out the period covered by the chart above. Because they pay interest, they are quite useful in international transactions. I’m sure there are other uses. Of course it’s true that rich people benefit from the interest, and particularly from the safety of the securities.

Does the fact that the Fed is buying so many mean they foresee needing that many to use to keep things from seizing up?

I don’t think so; that’s just way too much. I saw a couple of articles saying that the Fed would buy up all the Treasuries issued pursuant to the CARES Act and other Covid-19 funding laws. I think the fact that the Fed isn’t buying all of it can be attributed to the desire of a lot of people for safety even if there is only a small amount of interest.

The sale of Treasuries functions as a reserve drain. For a long time this was necessary to maintain the Fed’s target rate, however, since 2008 the Fed pays interest on reserves directly, so the reserve drain aspect of Treasury sales has become less important. Nonetheless, there is still a need to manage reserves.

Why manage reserves since we pay interest on them?

Money is debt. If the government isn’t in debt, you are.

David Graeber: debt and what the government doesn’t want you to know – video

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/video/2015/oct/28/david-graeber-what-government-doesnt-want-you-to-know-about-debt-video

Kelton describes several theories of money in the paper linked in footnote 3 to this post.

Very interesting. Your article led me to think of “printing” money as a dilution of the currency, hence inflation. But if people and institutions worldwide are willing to purchase yellow money with green at 0% interest, hey, keep the presses rolling. We live in a crazy time.

Hertz goes chapter 11 and then is able to sell stocks thus diluting their value zero. Seems like a mathematical impossibility but what do I know, I’m just a physicist.

Why not a digital currency controlled by the treasury?

The idea of dilution springs from the idea that dollars are convertible into some other commodity, say like gold, of which there is a fairly fixed amount. It’s better to try to think of dollars as a way of keeping score in a game, just like we keep score in basketball: scoring more points doesn’t make the first points less valuable. The thing that causes problems is inflation, not the number of points or green or yellow dollars.

In fact, the dollars are a digital currency, just numbers in your bank account.

The author writes…

” In the last few months, the Treasury has been selling securities and the Fed has been buying about 70% of them.”

This gives the impression the Fed buys securities directly from the Treasury, in essence, directly “funding” the government.

This is incorrect. The Fed buys government securities in the secondary market. In other words, it is buying securities that have already been purchased by dealers and, indirectly, by the public.

Well, in this context of Fed security purchases, “the secondary market (“the Open Market”)“ is in actuality a nice facade on top of what is in reality a favored club of about 22 bank partners granted a monopoly on purchasing from the Fed Bank of New York, who have special standing and aren’t ever audited by it.

This system was all but created so that it could with a straight face suggest that there’s a normal free market in between the Treasury and the Fed which exists as a buffer between interests of Treasury & Fed, rather than hand-picked yes-men subservient to interests of either.

That’s right in the context of the initial issuance of Treasuries. In fact a lot of us criticized the Fed for it’s purchases of Treasuries after the Great Crash because it guaranteed this group a profit: it could buy the securities and then sell them to the Fed at a small mark-up at no cost. Given the amount of Treasuries being marketed this was a sizeable giveaway.

Makes you wonder why we need to sell bonds at all apart from perhaps a small number to help control interest rates?

I graduated with two ECON degrees in 1975-1977, and I’ve been depressed since “voodoo economics” and the Laffer Curve at the level of economic analysis that was floating around the popular understanding of government economic policy.

I know other people who are replying have thoughts about the mechanics you described, but I wanted to thank you for your post. And, of course, it takes a village to figure out what we’ve been doing wrong for 40 years.

I think most people can understand this intuitively. What I’m really interested to hear is how Kelton addresses inflation risk.

Looking forward to more analysis on Keaton as well,and have saved the cites for reading this weekend.

Regarding inflation – I’d like to know why it is seen as a risk for the majority of people? At a fundamental level, if I am in debt (house mortgage for example) inflation matched with similar rise in my salary is a good thing. If I have all my money in the bank (wealthy from generations of inheritance that I didnt create/work for) I would be concerned about inflation.

Then we look at recent examples of potentially inflationary actions – GFC actions by the Australian government, no noticeable change to inflation, outcome of not entering a recession.

There’s a Cato study of 56 hyperinflations throughout history. How many were initiated by central banks printing too much money? Answer: zero. All stemmed from shortages of goods / balance of payments problems. So the French army shut down the industrial heart of Germany (the Ruhr) after World War I, and (never mind reparations) a shortage of goods led to the Weimar inflation. Rhodesian farmers left Zimbabwe, and a country that previously fed itself had to import food.

So “cost-push” not “demand-pull” is the origin of typical inflations. The oil shortages of the ’70s is another example.

Would “printing” lots of money cause inflation. According to its own audit, the Federal Reserve extended $16 – $29 trillion in credit to the financial sector in 2007-8. No surge of inflation registers on any measurement, public (CPI) or private (Shadowstats, MIT’s “Billion-Price Index”).

The Power of Market Fundamentalism: Karl Polanyi’s Critique. By Fred Block and Margaret R. Somers. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2014.

The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origin of Our Time, By Karl Polanyi. 1944 (Farrar & Rinehart)

FWIW, this stuff is the kind of thing that for many reasons (mostly negative and to my detriment) I prefer to ignore, and I certainly will not follow up with the various cites so helpfully listed (I acknowledge my self-incurred damage).

That said, this article even more than the last has educated me immensely, and I will keep reading this series, and I thank you, Mr. Walker (and even those citing the other material that I shall not read).

You can agree or disagree with Steph Kelton. I have done both. And can very honestly report she can argue and defend her posit a LOT better than people think. She even got to me.

I think a small-scale test case experiment would absolutely be a worthwhile exercise, and we have the perfect candidate program: the U.S. Highway Trust Fund projects. Its main account ($20b per month) + mass transit account ($8b per month) account for 28,000,000,000.00 a month of revenue that then gets passed through to State DOTs to complete their prioritized highway (roads and bridges) infrastructure needs. This is $360,000,000,000.00 per year and then let’s do a it as a 10 year experiment: $3.6T. Let the U.S. Treasury just print $3.6T new dollars that gets distributed to all of the States in accordance with the current Trust Fund calculation. Let them complete the entirety of their 10-year scoped infrastructure needs and then let’s measure the benefit to society; the benefit to those States, and the benefit to life in the U.S.

Highway Trust Fund is an attractive target for several reasons: 1) U.S. Infrastructure is apolitical; regardless of the political party, everyone understands the need for people, goods and services to safely make their way from point A to point B. 2) The Trust Fund is catastrophically being victimized by the success of improved environmental conditions; the Trust Fund is funded by gas taxes, which since the widening spread and adoption of green cars has set the Trust Fund revenue, it’s mechanism to exist, on a perilous negative slope. When we have successfully ended gas transportation, the income into the Trust Fund will be $0, despite the costs of maintaining the infrastructure remaining. None of the current alternatives (black box tracking of user miles with fee paid yearly, user-fee tolling, etc.) remotely hold any of the benefits that current “paid-at-the-pump” system holds.

I would venture to guess that the benefits of minting new $3T dollars in return for 10 years of completed infrastructure more than pays for that cost, thus increasing the supplies of goods and services, and therefore counter-pressuring any tendency of inflation that resulted from the increase in money supply. We have to do something radical in terms of funding the declining Highway Trust Fund in any case, and the 10 years would also allow a reasonable transition away from current but declining gas-tax funded system.

There may be other industries or systems where a test of the benefits of the costs could directly attack any inflationary pressure from printing new dollars, but the Highway Trust Fund projects offer an ability to hold a controlled, limited test case experiment, and its funding model is already imploding in any case.

If we remove gasoline entirely we’re just going to end up with electricity “pumps”, which will be taxed atrociously to make up for home electricity most likely.

At least one possibility I would think of

We can expect it is not going to be 1 for 1 switch: everyone or family that currently owns a gas-guzzler would instead own an amp-eater. In the same time frame, we’re already seeing radical and novel approaches to car ownership with coming and growing advent of semi- and autonomous vehicles. This opens door to ride-shares, co-ops, etc.

You would not own battery car; you pay monthly ride-share fee into a fleet co-op. When you need a car to go to work or store, you push the button in your ride-share app, and the robot car arrives, picks you up, and drops you off.

Adoption of this will already have been made easier with COVID-19 and people already relying more on online purchasing for normal goods and services.

Yes, the ride-share fleet would then pay the electricity tax; but it’s going to be based on different factors. The amount of revenue from “pay-at-electricity-pump” will be far smaller, because there will be much less individual owners. And the ride-share corporations, Google Car Fleet with 50,000 cars across country will be able to leverage and lobby far better terms for its own “pay-at-electricity-pump” tax paid.

…which would lead to changes in land use. No more need for individual garages. Parking lot use would change, too. It reminds me of that joke about when cars were first invented.

The second person says to the first: “But they can’t make them go more than 15 mph.”

First person asks, “Why not?”

Second person replies, “Because it would scare the horses.”

I am not sure I follow but the availability of resources certainly affects inflation. NoT enough labor or machines or widgets and the prices will go up.

Thanks for a great summary, Ed.

I’m listening to the book on audio, and noticed that Kelton tweeted 6/18 that her publisher just put out a new [hard cover or pbk?] book jacket highlighting: “NYT Bestseller”.

Incredible.

(I have an iBook audio edition, and just re-checked iBooks; however, the book jacket image is not updated online as of 3 pm PST. Amazon has this title tagged as a Bestseller, which is helpful for buyers. However, the ‘Best Seller’ information has not yet been highlighted in the online image of the book’s jacket, so it’s a safe bet that any downloads will also show the older image.)

Having spent several years of my life around eComm, I have observed that such seemingly tiny details make a difference, so if you or bmaz are in contact with Ms Kelton, FYI. (FWIW, I think the concept for the book’s cover is terrific.)

Particularly as this title is newly published, small details make a difference for many potential buyers: so many books, so little time! If 100,000 eyeballs of busy people with busy lives are deciding how to commit their reading time, every little bit of credibility makes a difference. Multiply exponentially for larger numbers of eyeballs. And headphones.

It may be that Kelton’s publisher has already sent updated book jacket images to the online retailers, and it’s taking 24 hours to upload the updated images. I will hope that is the case, but wanted to send [an extremely] public alert, as I have found such details actually do make a difference at scale: the bigger the scale, the larger the difference.

I’m hoping @Lawrence or one of the MSNBC or CNN or PBS programs books Kelton pronto. I’d swoon if Ali Velshi or Stephanie Ruhle (both with backgrounds in Biz reporting) interviewed Kelson; they are passionate about economics.

And this book would be absolutely terrific podcast material ;^)

I am discovering, listening to “Deficit Myth” as I walk, that on my first walk, I had a mental image of the US deficit as a terrifying ‘sea of red ink!!’ [cue Paul Ryan or Maggie Thatcher bleating, with sirens wailing in the distance, and the USS Titanic sinking beneath stormy waves]. A frightful, terrifying narrative and imagery.

However, in the chapter you summarize here, I began to visualize the US ‘balance sheet’ in terms of ‘assets’ the US possesses: stunning national parks, outstanding public schools (in some neighborhoods), acres of fertile farmland, burgeoning research universities, playgrounds with healthy kids, postal services in every community, municipal water and sewer systems…. A much more vibrant collection of images that, frankly, had never occurred to me in all my years of pondering economics.

The newer visuals may not be a Copernican constellation, but it’s definitely a mind shift.

Long overdue, and I’m savoring it with every step on my walks.

I have been reading Ellen Brown’s work, especially her articles about establishing State banks to fund important work rather than working with robber barons on Wall Street.

Positive Money in England is doing great work on this issue as well.

And local currency movements that keep cash circulating in communities are amazing. I bet Yes Magazine has some excellent articles on the subject.

Great to read this discussion.