Rural Roulette: The Three-Day Church Event

CNBC posted a list of the highest COVID rates per 10,000. In general, it includes two kinds of places: metro areas (NYC and environs, New Orleans, and Detroit), and ski resorts (the counties where Sun Valley, Crested Butte, Park City, Vail and Beaver Creek, and Aspen are).

There are two exceptions to that rule (though I expect Otsego County, MI may soon be on the list, based on a cluster I don’t yet understand): Dougherty County, GA, which I noted in this thread. That’s an outbreak tied to two funerals, especially that of Andrew Mitchell.

The service was for 64-year-old Andrew J. Mitchell, an Albany native who worked in custodial services and who died from what his family believes was heart failure. Mitchell came from a large family, and on Feb. 28 as many as 100 people came by the funeral home for visitation. The next day, seven of his siblings attended the funeral, along with dozens of his nieces, nephews, cousins and their own families. Some guests traveled in from as far away as Louisiana, Washington, D.C., and Hawaii. They greeted each other with tight handshakes, long embraces and kisses.

“The minister, he was shaking pretty much everybody’s hand, just giving the family comfort and condolences,” Mitchell’s niece Chiquita Coleman said. “The funeral home officiants, they were kind of doing the same thing. That’s kind of their job, to give comfort. So there was a lot of touching and hugging and hand-shaking.”

Afterward, chapel workers at the exit handed out memory cards. Later, there was a repast at Mitchell’s house and a gathering at the home of a sister.

In the days and weeks following, at least two dozen Mitchell family members fell sick with flu-like symptoms.

The other is Cleburne County, Arkansas, a county of just 25,000 people. That cluster is tied to a 3-day event at a local church.

Nearly three dozen cases of covid-19 have been diagnosed in people who share a connection to a church in Cleburne County, while others at the approximately 80-member congregation have been tested and are awaiting results.

[snip]

“It appears, from what I know at this time, most of the cases that we have in our county” are related to the Greers Ferry church, said Jerry Holmes, county judge of Cleburne County, who restricted public access to county offices last week and shut off access completely as of Monday.

Cleburne County, population 25,000, had 28 positive tests and 35 negative tests as of 7:35 p.m. Monday, according to the Arkansas Department of Health. Only Pulaski County, population 393,000, had a higher number of positive tests at that time, 62. All five counties bordering Cleburne had at least one positive test, including Faulkner County, which had 10.

Shipp’s count of 34 people is an updated count after reaching out to church members Sunday evening to check on them. Before then, Mark Palenske, the church’s pastor, had said in a Facebook post on the church’s official website Sunday that 26 people linked to the church had tested positive, including himself and his wife, Dena. The Palenskes could not be reached for this article.

Shipp said all but three of the people at the Kids Crusade were members or staff at the church. The three nonmembers who later tested positive for the virus were Thomas and Angela Carpenter, missionaries who had brought the three-day program to the church, and a child.

The Carpenters are listed as missionaries for Word of Grace Assembly of God Church in Hope on its website, and could not be reached at the church Monday.

The county has just one hospital and it has no ICU beds. And Arkansas is one of the states that has done least in response to this crisis, which makes it likely the disease will continue to spread from this one cluster.

Tourists, visiting missionaries, grieving friends and relatives of a long-standing community member. These are the ties that link rural communities across the country to a global network of virus. While many people in these rural towns believe they’re a world away from the outbreak in NYC, and therefore have to take none of the drastic measures to stop the spread, these same rural communities are even less prepared with the aftermath. Not only don’t their local healthcare facilities have the resources to treat this disease, but residents are more likely to be older, in ill health, and lack health insurance.

Update: The same kind of event — a church event — seems to behind a cluster of cases on the Navajo Nation.

A church gathering here earlier this month may be linked to a dozen confirmed cases of coronavirus and at least two deaths.

The participants in the large gathering that congregated March 7 at the Chilchinbeto Church of the Nazarene Zone Rally — a meeting in which pastors deliver messages to their members — may have all been exposed to coronavirus by at least one person who later tested positive for the disease.

Several people who attended the rally or who had family members who did later tested positive for the virus.

Before they could be tested, two people — one in LeChee, Arizona, and one in Chilchinbeto — died of respiratory symptoms, according to local sources.

[snip]

Confirmed cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, in the Navajo Nation on Tuesday evening rose to 49 from 26 late Saturday. Cases include 30 from Navajo County, seven in Apache County, six in Coconino County, four in McKinley County, and two in New Mexico’s San Juan County.

Most of the 30 coronavirus cases from Navajo County are tied to the zone rally, where one pastor was coughing as he gave a sermon, according to sources.

The rally ran concurrently with a “Day of Prayer” event at the Chilchinbeto Chapter House where chapter officials and some members of the church had a prayer service in response to the coronavirus outbreak. Everyone — pastors and members of all churches — were invited to the prayer service.

The LAT has an article about how poor communication and limited resources (including no running water in some cases) add to the challenges of a poor population with little access to medical care.

I suppose it’s a positive sign that testing is finally trickling down far enough that this sort of contact testing is happening.

In Arkansas they did get drive through testing, but after it became clear there was a cluster, I think.

On the Navajo Nation, they’re having to go door to door just to warn people of potential exposure.

Speaking of “door-to-door”, I live in L.A. and had a weird incident on Friday. Sitting in my living room lounge chair and looking at my computer, suddenly my front door opened and there was a homeless guy standing there. Startled, I asked him what he wanted and said “Sorry, I thought this was my house” and walked away. He seemed confused and I had the distinct impression that he had no idea there was a pandemic going on at all. I Lysol’ed my front door handles after that and am now keeping my front door locked – strange days are here…

Gaylord, the main city in Otsego County, Michigan, is a major destination for winter sports: downhill and cross-country skiing, snowmobiling, snowshoeing, and ice fishing. “Gaylord OWNS winter!” claims the Gaylord Area Convention and Tourism Bureau. https://www.michigan.org/city/gaylord#?c=45.0166:-84.6570:12&tid=564&page=0&pagesize=20&pagetitle=Gaylord

That could be it–but it really hasn’t been winter here, much.

Possibly down state people stopping in Gaylord for gas or coffee or lunch or supplies on their way farther north or to their winter cabins in the area.

Betting it was either a cluster of spring breakers or a trip related to the local high school.

Somebody got on a plane and then ended up in close quarters with others when they got back.

EDIT: Looks like one person had international travel, according to this March 16 report —

Might have nosocomial transmissions if Otsego Memorial wasn’t ready for this guy to walk in with COVID-19.

On March 26 NW Health Department said the six cases are community acquired. Wonder if the same guy was the county’s index case, responsible for the spread?

EDIT-2: Gaylord had a few things going on in spite of the not-so-wintery weather. But might have been something innocuous like a trip to the local watering hole that encouraged a cluster.

also the site of michigan’s central national guard camp, busy every weekend, draws from posts all over the state

An interesting observational experiment on the consequences of not practicing social distancing.

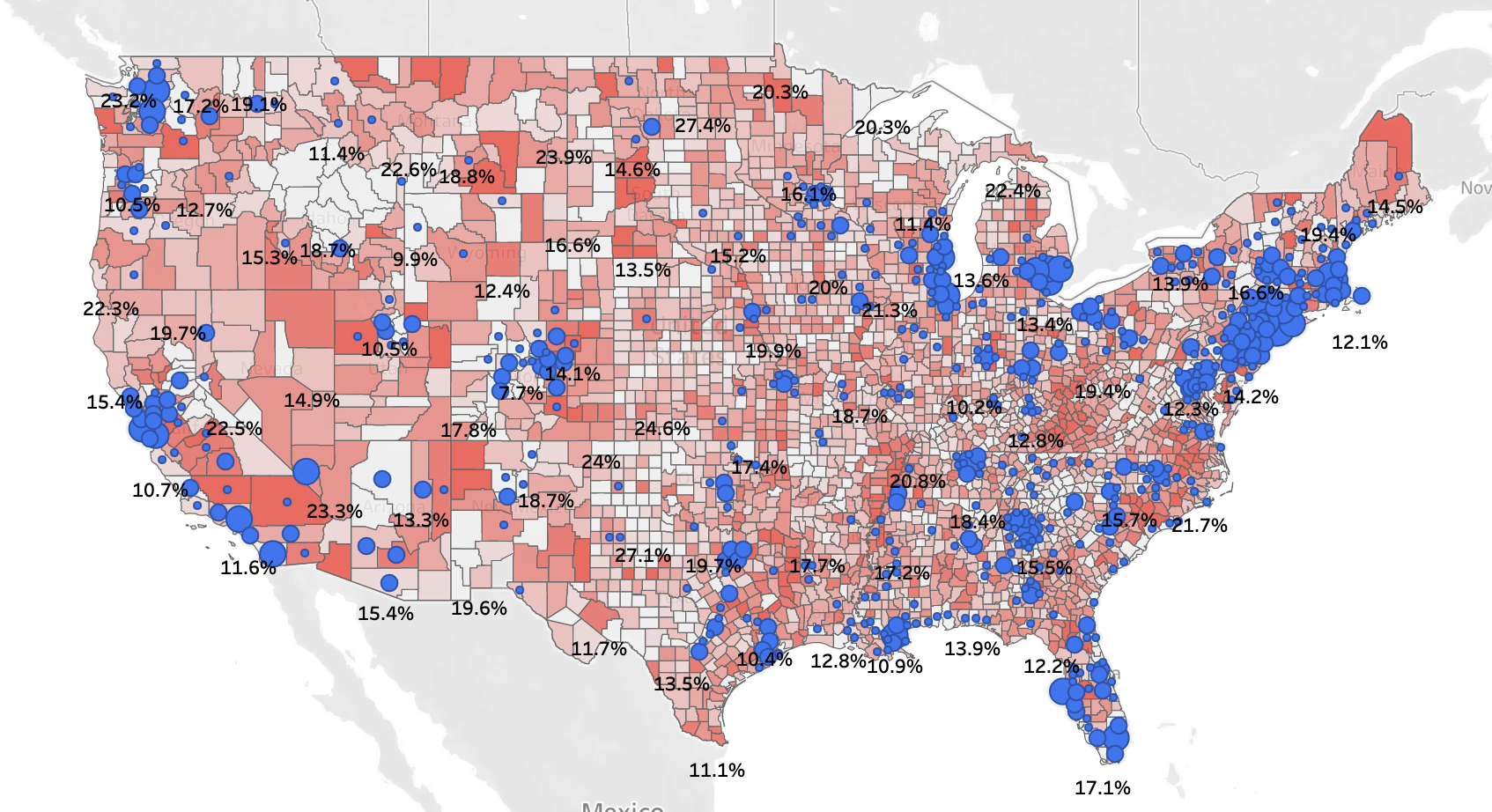

“…we analyzed secondary locations of anonymized mobile devices that were active at a single Ft. Lauderdale beach during spring break. This is where they went across the US:”

https://twitter.com/TectonixGEO/status/1242628347034767361

Yup. And a chunk of those phones went to Detroit metro area.

… and if the went back to college campuses, and were dispersed after that back to their homes, it’s going to go all over the place!

And remember, that’s just from a single beach in Fl!

I missed this originally. Very powerful analysis and shows just how mindless the behaviors were (and in some instances continue to be).

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch has a big story today with the headline “Just a Matter of Time: Hospital-poor rural Missouri braces for the coronavirus“. A taste:

It’s heartwrenching.

There are now 115 cases confirmed on the Navajo Reservation. The reservation is a huge, remote area, larger than many states. A lot of villages are served only by a dirt road (mud in season). Many Navajos live dispersed from a village and communications and utilities have been limited up until recently. For many, water comes from wells with scarce, confined aquifers and it is an arid environment. Quite a few challenges if the virus gets a foothold, though some advantages if people isolate, and avoid crowds.

https://www.kob.com/albuquerque-news/115-confirmed-positive-covid-19-cases-on-navajo-nation/5687088/

Fortunately, the Indian Health Service got a big chunk of support in the $8.3M COVID-19 appropriation passed by Congress at the beginning of March.

Unfortunately . . . take it away, Politico:

/facepalm

As usual, all talk, no action. Wow, does everyone in DC belong to the gang that couldn’t shoot straight?

Washington DC, a bastion of straight shooters…

I’ve also read that the various nations have to ask for it individually.

this is something odd here. I understood that the CDC and the public health service officers who essentially run it have a very long history with the Indian tribes, from the southwest to Alaska. as with the hidden testing snafu (which it seems was based on few rule-making favoring private companies developing a test), i would look for Alex Azar’s fingerprints somewhere. in my view the guy just hasn’t gotten enough credit for being a slick, silent activist.

In Colorado there is an asterisk stating that *visitors are being counted in the county they were identified.

Which got me wondering how the rest of the stats are being registered across the country?

If someone drove 30 miles to get a test, is their home address registering the case or the country that is doing the testing? Does a community look “clean” on map because people were tested an admitted to a hospital across a state or county line?

In Louisiana, another church gathering, and the neighbors are Not Happy:

https://www.sfgate.com/news/medical/article/Hundreds-at-church-flout-COVID-19-gatherings-ban-15164855.php

As I understand, Lee County, AL, where Auburn University is located, is a hotspot in Alabama and also has a cluster associated with a specific Christian church.

The cell phone analysis is horrifying. My nephew is a student at Auburn and was on the beach in the Florida panhandle for spring break with his friends (don’t blame me). I suspect that Auburn is about to get a burst related to spring breakers who live in off campus apartments and are still around. Same with most other college towns in eastern and central US.

the problem of rural hospitals disappearing, one-by-one blinking out like snuffed candles, has been a disaster building for two decades. i attrubute this to two key matters:

1) the deliberate refusal by Republican legislatures in the south to extend Medicaid benefits which would impact rural areas very positively in terms of health, invluding increasing the viability of hospitals. I regard this refusal to be based largely on racial animosity.

2. the business behaviors of medical corporations, including private equity bucaneers, who dump rural hospitals as

they become less able to contribute to the bottom line dollar.

https://bigthink.com/strange-maps/life-expectancy

I don’t know this particular source but this map shows up in lots of places. there is a still better, much starker, map of life expectancy by county, but I can’t put my finger on it quickly. my recollection is that it matches rural poverty and race remarkably well.

the key remedial state gov’t action has been on the table, complete with generous federal incentives, since the affordable Care act became law in 2010. caring political will has been missing – “with malice toward none, with charity to….”

the Catholic church, or some of its allied organizations has been said to be buying up failing rural hospitals. whether this is a straight up act of Christian charity among the poor, for which the church has an ages long history, or an ideological gambit based on controlling women’s reproduction, i don’t know. it can have both consequences, but how many hospitals can even a wealthy private organization support? this is a situation where all of society, represented by the state, must provide relief and support a healthy population.

The social horrors of “just-in-time” production (heightened risks and gutted resilience) and the rapaciousness of modern financial priorities have been occupying the heights of large hospital management for some time. But hospitals are not unique: a plague of MBAs has descended on colleges, universities, and governments, too. It has led those institutions to mimic the business methods and priorities of their boards of governors. It’s another deadly virus that has not begun to run its course.

The RC church has been selling or closing hospitals – some they still have as part-owners. (They’re losing money on the ones they’re closing/selling.)

thanks, p. j.

I think i have read that the church is now buying rural hospitals that threaten to close, but can’t find a supporting cite. it is however a major owner of hospitals in this country. for the purposes of this problem that may not be relevant to the rural hospitals problem I am concerned about here.

https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/how-catholic-bishops-are-shaping-health-care-in-rural-america/

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/10/health/catholic-hospitals-procedures.html

I have no idea what lies behind the decision to close this Kansas community’s hospital this week, but it certainly illustrates the rural community health problems and it’s lack of control over it’s fate. strange timing to say the least:

https://www.wellingtondailynews.com/news/20200313/sumner-community-hospital-closes-in-wellington

it’s 35 miles to witchita.

Another fundy pastor has announced he’s going to have a big live service for Easter, because Jeebus.

https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2020/3/31/1933078/-Friend-of-pastor-arrested-for-keeping-megachurch-open-announces-big-Christian-Woodstock

I think “depraved indifference” applies – one charge for every person that gets sick after one of these in-person services. For all of the pastors who think that they shouldn’t have to obey distancing rules.