A Virus Does Not Care

A virus does not care. A virus simply wants to reproduce, and for that it needs a host. A virus does not care about who that host is. A virus just wants a place to live, eat, and reproduce. A virus does not care if it makes the host sick. A virus does not care if it kills the host. This is the First Rule of Viruses: A virus does not care.

In 1918, as WWI was being fought in Europe, a virus emerged at Camp Funston, in the area of Fort Riley, Kansas. This virus did not care about the war. The virus did not care about Our Boys who were preparing to go fight that war. The virus did not care about the farmers in the Kansas fields, who dropped at their plows in the fields when the virus attacked.

A virus does not care.

The soldiers from Fort Riley went to the front lines in Europe with their guns, their ammo, their packs, and their gear, and they took that virus with them. It attacked their comrades in arms, and it attacked their enemies across the trenches.

A virus does not care.

The virus attacked King Alphonso XIII of Spain. Wherever the virus appeared, people began to speak of “the Spanish Flu,” going back to the widely-reported news of the mighty king it brought low. But the virus didn’t care. The virus attacked soldiers. The virus attacked ordinary villagers. Some lived, and some died.

A virus does not care.

The virus spread across the US, just as the war was beginning to come to an end. Bonds were being sold to pay for the war, and soldiers were starting to come home. The virus did not care about the bonds. The virus did not care about the homecoming celebrations being planned.

A virus does not care.

But people care, and they care about lots of things, and that’s where things got worse. People care about their status. People care about their businesses and their livelihoods. People care about parades the celebrate the end of a long and ugly war. People care about gathering in the corner bar with their friends, and playing sports in the local parks. People care about staying safe when danger threatens. People care about singing and dancing and enjoying life. People care about a million and one things, but a virus does not care about any of those things.

A virus does not care.

By 1918, people knew how to deal with a spreading virus in two broad ways: quit interacting so closely with others and practice good hygiene (both individually and as a community). They knew that beating a virus requires that a community care about itself just as much as the virus does not care at all. Give the virus an inch, and it will continue its deadly spread.

Because a virus does not care.

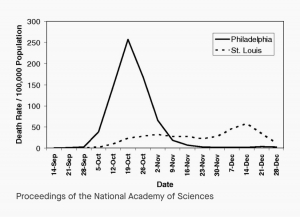

Some communities enacted a wide variety of what epidemiologists today call “nonpharmaceutical interventions” – prohibiting large public gatherings, closing businesses, shutting down churches, suspending schools, and so on. Other communities enacted some of these measures, but not all of them. Some communities took few measures, or decided “We’ll prohibit large gatherings, but not until after the big parade next week.” On the spectrum from “we need to shut everything down” to “we need business as usual,” St. Louis was on one end of the spectrum, and Philadelphia was in the other.

By late September, Jefferson Barracks [a US military post in St. Louis] went under quarantine as the first soldiers came down with the flu.

In early October, city health commissioner Dr. Max C. Starkloff ordered the closure of schools, movie theaters, saloons, sporting events and other public gathering spots. Churches were told to suspend Sunday services. At the time, with nearly 800,000 residents, St. Louis was among the top 10 largest American cities. . . .

Theater owners, as some of the largest taxpayers at the time, protested the closures. Musicians and entertainers claimed the quarantine threatened their careers. Others were delighted — anti-alcohol leagues that were forming in the runup to Prohibition went on the lookout for taverns that violated the shutdown, [director of library and collections at the Missouri History Museum Chris] Gordon said.

Within two days of the quarantine, eight soldiers at Jefferson Barracks were dead, another eight residents died at St. Louis City Hospital and the number of area flu cases topped 1,150.

Jacob Meeker, a St. Louis congressman, died Oct. 16, six days after touring Jefferson Barracks. He was 40.

With the flu continuing its rampage, Starkloff imposed a stricter quarantine in November, closing down all businesses with few exceptions including banks, newspapers, embalmers and coffin makers, according to Post-Dispatch archives.

The American Red Cross shifted from making bandages to face masks. Volunteers passed around blankets and vats of broth to flu sufferers. An ambulance waited at Union Station to take any sickly train passengers directly to the hospital upon arrival. Police officers and mail carriers wore masks on their daily routes.

And as these measures took hold, it slowed the virus down.

In an effort to boost morale for the war and also to sell bonds, the city of Philadelphia threw a parade that drew 200,000 people, despite warnings that the Spanish flu was spreading among the soldiers who were about to head off to World War I and would be in the parade.

That didn’t turn out to be a good idea.

Days later, hospitals in the area were filled with patients suffering or dying from the Spanish flu.

Weeks later, more than 4,500 people in the Philadelphia area died from the virus.

The graph at the top of the post, from a 2007 article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, paints the picture of these two approaches in stark, and by now familiar, terms.

Unlike a virus, people get to choose what they care about and how that care will be expressed. In 1918, to borrow from the Grail Knight, the leaders of Philadephia chose . . . poorly, while the leaders in St. Louis chose wisely.

Today, like many places, I and my neighbors in metro Kansas City (on both sides of the state line) are living under a locally-imposed “stay-at-home” order, with school buildings closed, business activity limited to those deemed essential and curtailing large public gatherings completely, including weddings and funerals.

You see, the leaders here know that a virus does not care. Other leaders, however . . .

From an interview on Fox:

Trump: I saw wouldn’t it be great to have all of the churches full—you know the churches aren’t allowed to have much of a congregation there. And most of them, I watched on Sunday online—and it was terrific, by the way—but online is never going to be like being there. So I think Easter Sunday and you’ll have packed churches all over our country—I think it will be a beautiful time. And it’s just about the timeline that I think is right.

A virus does not care about whether churches are full or empty on Easter. A virus doesn’t care if it is beautiful. A virus doesn’t care about your personal faith or lack thereof. In Omaha in 1918, Rev. Siefke S. de Freese, a seemingly healthy 35 year old pastor, led worship on a Sunday, then quickly died days later. A virus does not care.

From yesterday’s coronavirus task force presser:

Q: Mr President, you just reiterated that you hope to have the country reopened by Easter. You said earlier you would like to see churches packed on that day. My question is, you have two doctors on stage with you. Have either of them told you that’s a realistic timeline?

Trump: I think we’re looking at a timeline, we’re discussing it. We had a very good meeting today. If you add it all up. That’s probably nine days plus another two and a half weeks. It’s a period of time that’s longer than the original two weeks, so we’re going to look at it. We’ll only do it if it’s good and maybe we do sections of the country. We do large sections of the country. That could be too, but we’re very much in touch with Tony and with Deborah whenever they [crosstalk].

Q: Who suggested Easter? Who suggested that day?

Trump: I Just thought it was a beautiful time, a beautiful timeline. It’s a great day. . . . I’d love to see it come even sooner, but I just think it would be a beautiful timeline.

A virus does not care if it is a beautiful time. A virus does not care if it is a great day. A virus does not care what you think. A virus does not care what you love.

A virus Does. Not. Care.

We can choose how we respond to an uncaring virus. We can choose like St. Louis did, or we can choose like Philadelphia. And for far too many people, my friends, that is a choice between life and death. And in 1918, even St. Louis didn’t get it completely right:

The quarantine was temporarily lifted Nov. 18 but reinstated when the flu roared back in December. By Dec. 10 the flu peaked in the city with 60 deaths in one day. After illnesses declined sharply, the quarantine was lifted just after Christmas.

Look at that graph again, and you can see the bump at the end of November when the quarantine was prematurely lifted. The virus came back, because a virus does not care.

I’m a pastor. I’d love to see my church packed to the rafters on Easter. I’d love to hear the trumpets leading a 1000 voices in grand hymns of celebration. But that’s not going to happen, because while a virus does not care, I do.

We’re going to be closed this year. Not because we want to be. Not because we lack faith. Not because we don’t care about worship. Not because we’re giving in to the virus. It’s because we care about ourselves and our community so much that we’ll give up this kind of gathering to defeat the virus. Anything less than a full community commitment to a choice like that, and the virus will not be slowed, because the virus does not care.

I pray that more local leaders, state leaders, and national leaders choose wisely, even as Trump seems determined to choose . . . poorly.

I pray this, because I know the First Rule of Viruses: a virus does not care.