Joshua Schulte’s Human Graymail Campaign Targets Mike Pompeo

“Graymail” is a term used to describe when a defendant attempts to make a prosecution involving classified information too difficult for the government to pursue by demanding reams of classified evidence that the government either has to water down to make admissible at trial or argue is not helpful to the defense.

As an example, Scooter Libby employed a defense that he didn’t lie to the grand jury about his efforts to expose Valerie Plame, but rather forgot about those efforts, because he was so distracted by everything scary he reviewed in daily Presidential Daily Briefs. He forced the government to substitute a great deal of information from PDBs and almost upended the trial as a result.

It has been clear for some time that accused Vault 7 leaker Joshua Schulte was employing such a strategy, but with a twist. He obviously has been trying to release as much classified information from the CIA as possible, both through legitimate means and via leaking it. But starting last fall, there was a dispute about how Schulte could serve trial subpoenas on CIA witnesses and whether he had to work through prosecutors to do so; Schulte argued the government was trying to learn his defensive strategy by vetting his subpoenas.

The dispute just surfaced again in the form of a government motion in limine to exclude 3 CIA witnesses and require Schulte to provide justifications for a slew of other CIA witnesses he has subpoenaed. At least 63 CIA witnesses have informed the CIA that he has subpoenaed them, and that’s just the ones who have informed the agency.

The Government understands that the defendant has served at least 69 current or former CIA employees with subpoenas in this case. This includes subpoenas for 23 individuals identified in a preliminary witness list the Government provided to the defense as a courtesy on August 16, 2019, which the Court authorized in an Order dated November 26, 2019 (Dkt. 200), and at least 46 additional subpoenas since then. That number reflects those recipients who have informed the CIA’s Office of General Counsel of the latest subpoenas, as required by CIA regulations.1

1 The Government does not know the precise number of subpoenas that the defendant has issued because the Government is only aware of the subpoenas issued to individuals who have reported receiving them to the CIA’s Office of General Counsel.

With respect to this slew of witnesses, the government asks just that Schulte be required to show that they have firsthand knowledge that is relevant to the trial that would not be cumulative.

But with respect to three, the government offers specific objections. The government’s objections to two — a covert field officer and the Center for Cyber Intelligence’s Chief Counsel — seem utterly reasonable. But the government’s objection to a third — Mike Pompeo, who was CIA Director when WikiLeaks published the leaks — is more dubious.

To the extent it’s discernible given redactions in the government’s motion, here are the objections to those three witnesses.

Lisa: Schulte has subpoenaed a woman pseudonymed “Lisa,” a “high up” customer of CIA’s hacking tools. Schulte argues that because CIA officers did not “warn” her about Schulte, it’s proof of his innocence. The government argues that Schulte is trying to call “Lisa” to testify in part to admit into evidence statements that he made to her, which would be hearsay designed to avoid taking the stand himself.

Erin: Schulte wants to call the Chief Counsel of CCI to testify about things she said in an FBI interview about other potential leads to find the culprit behind the theft. Apparently, she raised an off-site event that took place between March 8-10, 2016 that might play a role. According to the original theory of the case, Schulte used an opportunity when everyone else was gone from the office, possibly during that event, to steal these files. But, as the government points out, Schulte didn’t ask “Jeremy Weber” anything about this event when he was on the stand, even though Weber attended it personally. They note Schulte instead wants to ask someone who wasn’t there — Erin — about it. Plus, as the government notes, Erin is the counsel for the victim of this crime, and as such is protected by attorney-client privilege.

Mike Pompeo: Finally, Schulte wants to call Mike Pompeo. The government wants to exclude Pompeo because, during the period when he was a CIA employee as its Director, he had no direct knowledge of the theft.

While Sec. Pompeo was undoubtedly kept informed about the consequences of the defendant’s crimes and the CIA’s response to secure its systems going forward, he–like virtually all similarly situated high-ranking government officials–received that information through briefings and summaries provided by others, which is quintessential inadmissible hearsay, rather than first-hand knowledge of the facts.

Except that’s probably not why Schulte wants to call him. In fact, I predicted Schulte would call Pompeo back in November.

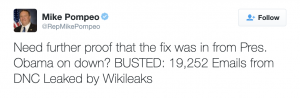

Notably, the government motion invokes the Senate’s recognition that WikiLeaks resembles “a non-state hostile intelligence service.” That may well backfire in spectacular fashion. That statement didn’t come until over a year after Schulte is alleged to have stolen the files. And the statement was a follow-up to Mike Pompeo’s similar claim, which was a direct response to Schulte’s leak. If I were Schulte, I’d be preparing a subpoena to call Pompeo to testify about why, after the date when Schulte allegedly stole the CIA files, on July 24, 2016, he was still hailing the purported value of WikiLeaks’ releases.

Because of the way the government has argued that Schulte’s choice to leak to WikiLeaks is proof he intended to harm the US, it makes then House Intelligence Chair Mike Pompeo’s celebration of WikiLeaks’ publication of the stolen DNC emails — a celebration that took place months after Schulte is alleged to have sent the emails to WikiLeaks — a pertinent issue.

Given what the government has argued, Pompeo might be required to take the stand and admit that he was just being an asshole who was happy to damage the US if it meant his party would benefit when he celebrated the WikiLeaks publication of stolen DNC emails in July 2016. Of course, that’s the last thing he wants to do — and if he did, his boss, who got elected by cheering such damage, might well fire him. Pompeo’s view of WikiLeaks in July 2016 is all the more relevant given that the government appears to be planning to make … something of the Schulte’s response to these very same leaks.

Schulte is clearly engaged in human graymail with this larger request, and I expect Judge Paul Crotty will agree to the government’s demand that Schulte show some particularized value to each of these CIA witnesses.

But given their efforts to treat WikiLeaks as a particularly damaging kind of leak recipient, I think Schulte may be able to make a compelling argument that Pompeo should have to explain his past enthusiasm for WikiLeaks’ publications.