Dominic Pezzola Suspects the FBI’s Cooperating Witness Is the Guy Who Recruited Him into the Proud Boys

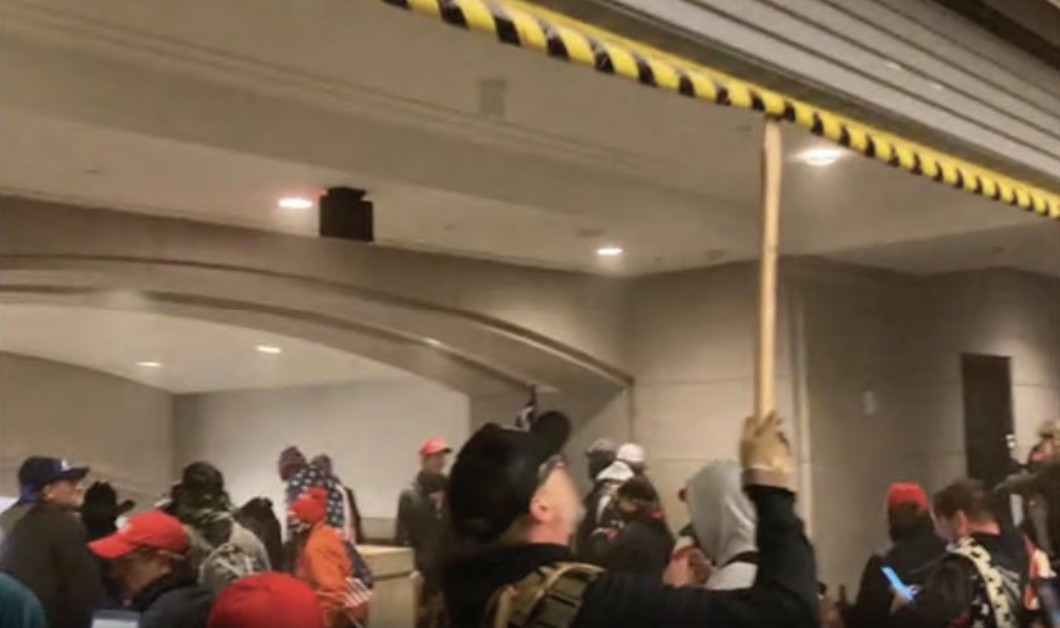

A number of people are pointing to this motion to modify bond by Proud Boy Dominic Pezzola, the guy who helped kick off an insurrection by breaking the window of the Capitol with a stolen police shield, reporting either that Pezzola is bidding to plead out or that that the Proud Boys are turning on themselves.

Both may be true.

But buried within the filing is a far more inflammatory allegation. Pezzola, the guy who kicked off the entire assault on the Capitol on January 6 in coordination with other Proud Boys, is suggesting that someone who came to serve as an FBI cooperating witness less than a week after an attack that purportedly took the FBI entirely by surprise, was actually the guy who recruited him into the Proud Boys and set him up with a thumb drive loaded up — unbeknownst to him, he maintains — with the Anarchist’s Handbook, including its bomb-making plans.

Pezzola makes the allegation by rebutting the claim he is dangerous, the basis by which Magistrate Robin Meriweather. came to deny him bail.

As Pezzola notes, Meriweather denied him bail not because of a presumption of detention or a concern he would flee. It was because he posed a danger to the public. Meriweather framed that presumed danger as arising from a thumb drive loaded with the Anarchist’s Handbook found at his home and the testimony of a witness.

In determining that Pezzola’s release presented “danger” to the community the Court cited 2 factors from the prosecution’s proffer: (1) the claim that Pezzola participated in a group conversation when others expressed an intention to return to DC with weapons to commit acts of violence; (2) recovery of a thumb drive with plans for making, bombs, poisons, etc.

Per Pezzola’s arrest affidavit, the witness was someone whom the FBI interviewed at least twice before obtaining an arrest warrant against Pezzola on January 13, just a week after the insurrection. The description of witnesses in the total universe of January 6 affidavits are totally inconsistent (in part because so many different FBI Agents wrote them), meaning we can’t conclude anything by the description an agent uses. Nevertheless, this one was always among the only ones that seemed to be an insider. The witness is someone who described Pezzola as “Spaz” right away (though elsewhere he is called Spazzo), described Pezzola as bragging about breaking into the Capitol, and he described the group — the Proud Boys — as capable of killing Nancy Pelosi or Mike Pence, and planning more actions.

The FBI has spoken to an individual your affiant will refer to as “W-1” for purposes of this affidavit. W-1 stated that W-1 was in Washington, D.C., during the protests that occurred on January 6, 2021.

W-1 stated that after the events at the Capitol as described above, he or she spoke to an individual he or she knows as “Spaz,” along with other individuals. W-1 stated that during that conversation, “Spaz” bragged about breaking the windows to the Capitol and entering the building. In a subsequent interview W-1 clarified that “Spaz” said that he used a Capitol Police shield to break the window. W-1 said that “Spaz” can be seen on the cover of many newspapers and recognizes him from those photographs. W-1 stated that other members of the group talked about things they had done during the day, and they said that anyone they got their hands on they would have killed, including Nancy Pelosi. W-1 further stated that members of this group, which included “Spaz,” said that they would have killed [Vice President] Mike Pence if given the chance.

I had thought this witness would be one of numerous Proud Boy hangers on who was hanging around in DC after the attack, but as we’ll see, Pezzola believes it’s the guy he commuted to insurrection with.

The witness first told the FBI that the Proud Boys were preparing an event on January 20th (which is consistent with other reports).

According to W-1, the group said it would be returning on the “20th,” which your affiant takes to mean the Presidential Inauguration scheduled for January 20, 2021, and that they plan to kill every single “m-fer” they can.1 W-1 stated the men said they all had firearms or access to firearms.

Then, in a later interview (again, remember that this is before January 13), the witness said maybe the next event wasn’t inauguration, but soon after. Whenever it was, it’d involve guns.

In a later interview, W-1 stated that the group had no definitive date for a return to Washington, D.C, but W-1 re-iterated that the others agreed there would be guns and that they would be back soon and they would bring guns.

The witness also misidentified Doug Jensen, the QAnon adherent who chased officer Goodman up the Capitol stairs, as someone else, presumably a member of the Proud Boys, only to clarify later that someone else was the individual in question.

In W-1’s initial interview with law enforcement, W-1 initially incorrectly the individual in the black knit hat in the foreground of this photograph as someone I will refer to as “Individual A.” W-1 later clarified that the person in the knit hat is not in fact Individual A and identified a different person in a separate photograph as Individual A.

Thus far, this witness sounds like he’s telling the FBI what he expects they most want to hear, something you often hear from informants trying to maximize their own value. By misidentifying Jensen, he may have falsely suggested the Proud Boys chose where to go in the Capitol. And by promising there would be more events, featuring violence (again, which is consistent with what public chatter was at the time), he heightened the urgency of case against the Proud Boys.

As Pezzola describes in his motion for bail, he suspects the person who said the Proud Boys had ongoing plans is a guy he drove home to New York with from DC.

Pezzola maintains no recollection of the referenced conversation but suspects if the conversation did occur in his presence it could have only occurred in the car on the return trip from Washington when Pezzola was asleep in the car. Upon information and belief, the CW is not detained. Rather he has reached an agreement where he is making allegations against others in order to avoid his detention for what is actually his greater involvement in the underlying events.

That would explain why William Pepe, also from NY, was named Pezzola’s co-conspirator: presumably both were in the same car speaking to the same guy, which is how the government had confidence that Pepe’s actions were coordinated with Pezzola’s and not, for example, the two other people charged with kicking off the attack on the Capitol, Robert Gieswein and Ryan Samsel.

As Pezzola describes, “it is alleged” that he’s just a recent recruit to the Proud Boys (something I don’t necessarily buy, but it seems to reflect Pezzola parroting back what he’s seen in discovery so far).

Pezzola’s alleged contact with the “Proud Boys” was minimal and short lived. It is alleged he had no contact prior to late November 2020. Upon information and belief, the prosecution alleges his first contacts occurred around that time. They principally amounted to meeting for drinks in a bar. Prior to January 6, 2020, there is no allegation that Pezzola took any action with the “Proud Boys” that was in anyway criminal or violent. His only event prior to January 6, 2021, was that he attended a MAGA rally in support of Donald Trump in December 2020. There is no allegation he was involved in any criminal or violent activity there.

He claims that the cooperating witness is actually far more involved in the Proud Boys.

Addressing these in turn: There is a claim as the prosecution pointed out that a “cooperating witness” claimed that Pezzola was present in a group when someone professed an intention to return on January 20, 2021, Inauguration day to instigate more violence. However, there is no claim Pezzola made those statements nor that he expressed a similar intent1 nor any intention to participate in any acts of violence, let alone murder. Although the defense cannot be certain it is believed the “cooperating witness” (CW) who has made these claims is actually someone who was a much more active participant in the “Proud Boys” than Pezzola, having been with the organization for a much longer time than Pezzola’s alleged association and much more active.

And Pezzola claims that the thumb drive showing possession of bomb making instructions was actually given to him by the guy he suspects of being the cooperating witness.

What was unknown at the time of the prior hearing is that the thumb drive at issue was given to Pezzola, probably by the Prosecution’s CW5 when that person was making efforts to introduce Pezzola into the “Proud Boys.”

Finally, Pezzola further alleges that the guy he suspects of being the cooperating witness confessed to spraying cops with pepper spray, an assault that has not been charged (only Giswein and Samsel were charged with outright assaults on cops).

Although it is impossible to know with certainty at this point, if the defense supposition about the CW is correct, that person admitted to spraying law enforcement with a chemical agent, likely “OC or Pepper” spray during the January 6 event.

It is true that Pezzola nods to making a plea deal in this filing.

Although the Court can play no role in disposition negotiations, via counsel Pezzola has indicated his desire to begin disposition negotiations and acceptance of responsibility for his actions. He seeks to make amends.

But there’s little chance DOJ can offer him a deal that will help him rebuild his life. Even in this filing, he admits he was attempting to stop the vote count, the goal of every overriding conspiracy charge thus far, which would be a key part of any seditious conspiracy case. He doesn’t deny he broke into the Capitol; he instead disingenuously downplays the import of being the first to do so, noting that numerous doors and windows were breached over the course of the day. His claim he has never used his Marine training since his service is inconsistent with the way he walked through the Capitol with much greater operational awareness than many of the other rioters. Plus, even in his first bail hearing, Pezzola insisted he was not a leader of the attack, which — if he was a recent recruit, makes total sense (and is consistent with Felicia Konold, someone else who played a key role, but who was just a recruit-in-progress). So he wouldn’t necessarily have that much information on anyone except those who gave him directions and the guy in the car, not necessarily enough to trade as the guy who kicked off the insurrection, even if he was acting on orders.

He’s likely fucked one way or another, not least because he’d be far less useful as a cooperator if everyone knew he had a plea deal.

But Pezzola’s allegation is troubling for several more reasons.

As noted, the FBI interviewed this cooperating witness at least twice before January 13, suggesting at the very least that the FBI reached out to him right away (or vice versa), rather than collecting more information on the person’s own role. And in spite of two variations in his story — misidentifying Jensen and equivocating about when the next operations were planned — his testimony was deemed credible enough to implicate someone he may have recruited and provided other the other damning evidence on.

The FBI knew that Enrique Tarrio and the rest of the Proud Boys were coming to DC for the January 6 events, which is how they were prepared to arrest him on entry in DC. They knew that during the Proud Boys’ previous visit, the group had targeted two Black churches. DOJ had investigated threats four members of the Proud Boys had made against a sitting judge in 2019.

And yet, not only didn’t FBI prevent the January 6 attack kicked off by the Proud Boys, they didn’t even issue an intelligence warning about possible violence.

It’s possible this witness genuinely did just reach out to the FBI and try to pre-empt any investigation into himself. It’s possible that as the FBI has done more review (including of video outside the Capitol, where a pepper spray attack on cops likely would have occurred), they’ve come to grow more skeptical of this witness.

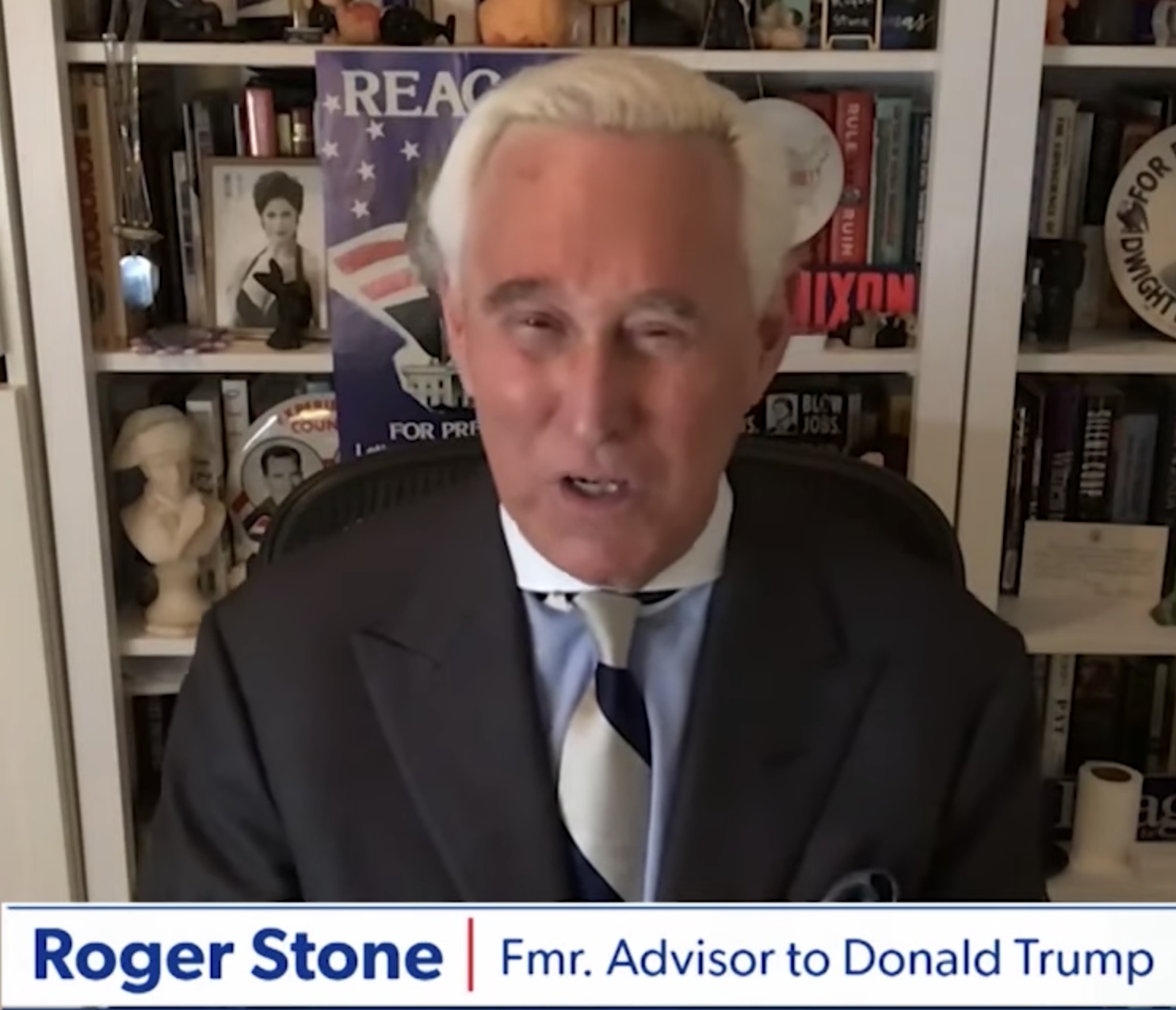

But it’s also possible that the FBI has ties with witnesses — possibly this guy, and very likely Rudy Giuliani interlocutor James Sullivan, who said he was in contact with the FBI — who have more information on those who set up this insurrection, rather than just busting down the window. Particularly given the unsurprising news that investigators are scrutinizing the role that Roger Stone and Alex Jones might have played (Rudy is not mentioned, but not excluded either), it seems critical that the FBI not adhere to its counterproductive use of informants targeting a group (no matter how reprehensible) rather than action.

The FBI has a lot to answer for in its utterly inconceivable failure to offer warnings about this event. If their informant practices blinded them — or if they’re making stupid choices now out of desperation to mitigate that initial failure — it will do little to mitigate the threat of the Proud Boys.

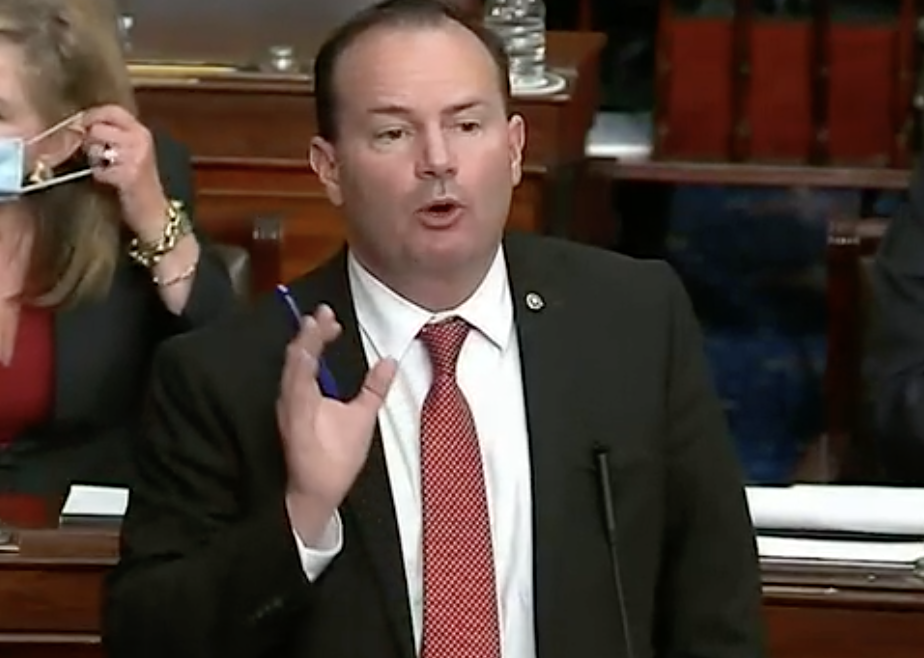

Pezzola

Pezzola