The Government Screws Up Attempt to Distinguish between January 6 Insurrection and Anti-Kavanaugh Protests

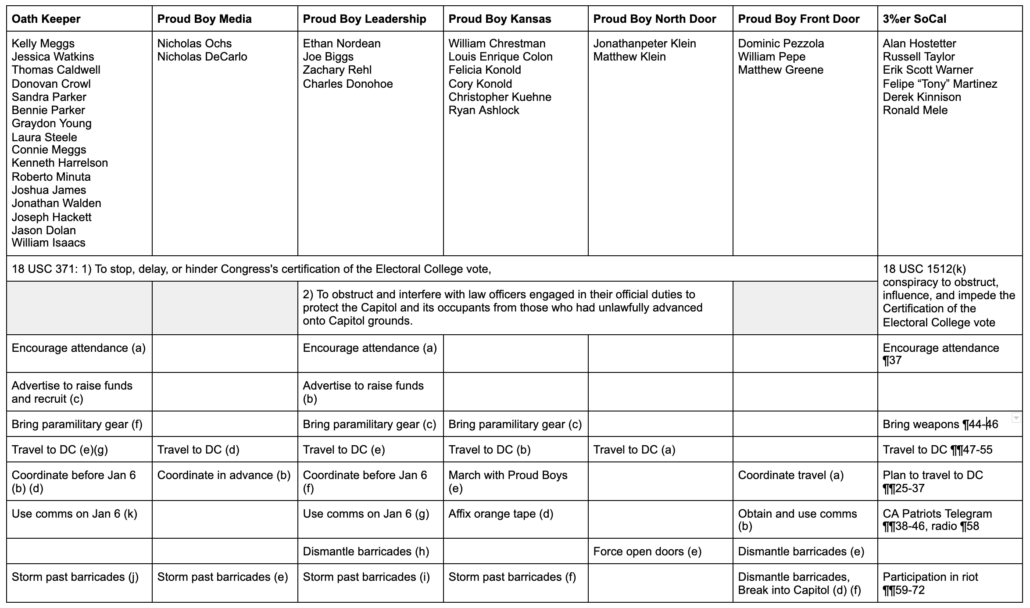

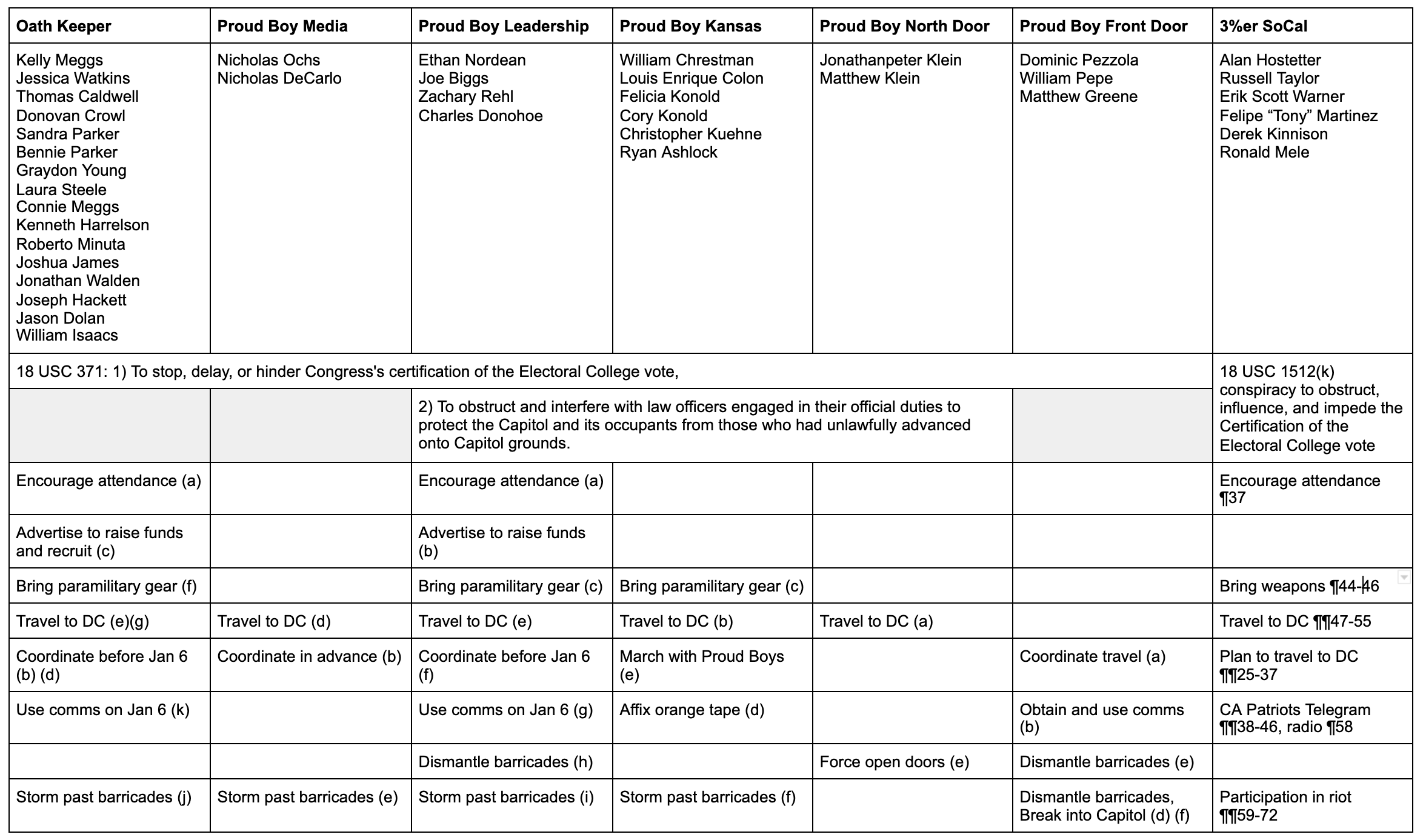

The government is obviously getting fed up with some of Ethan Nordean’s legal challenges. I can’t blame them for being impatient with Nordean’s claims that, so long as cops at one of four barricades he passed on his way to insurrection weren’t knocked down, it means he had no way of knowing he wasn’t welcome.

But they fucked up, badly, in what would otherwise be an important argument to make. In his reply brief to his motion to dismiss his entire indictment (here’s the government’s response), Nordean made an argument that right wingers love to make, that the Kavanaugh protests were just like the insurrection, yet those protestors weren’t charged with the same felony charges that January 6 insurrectionists are being charged with.

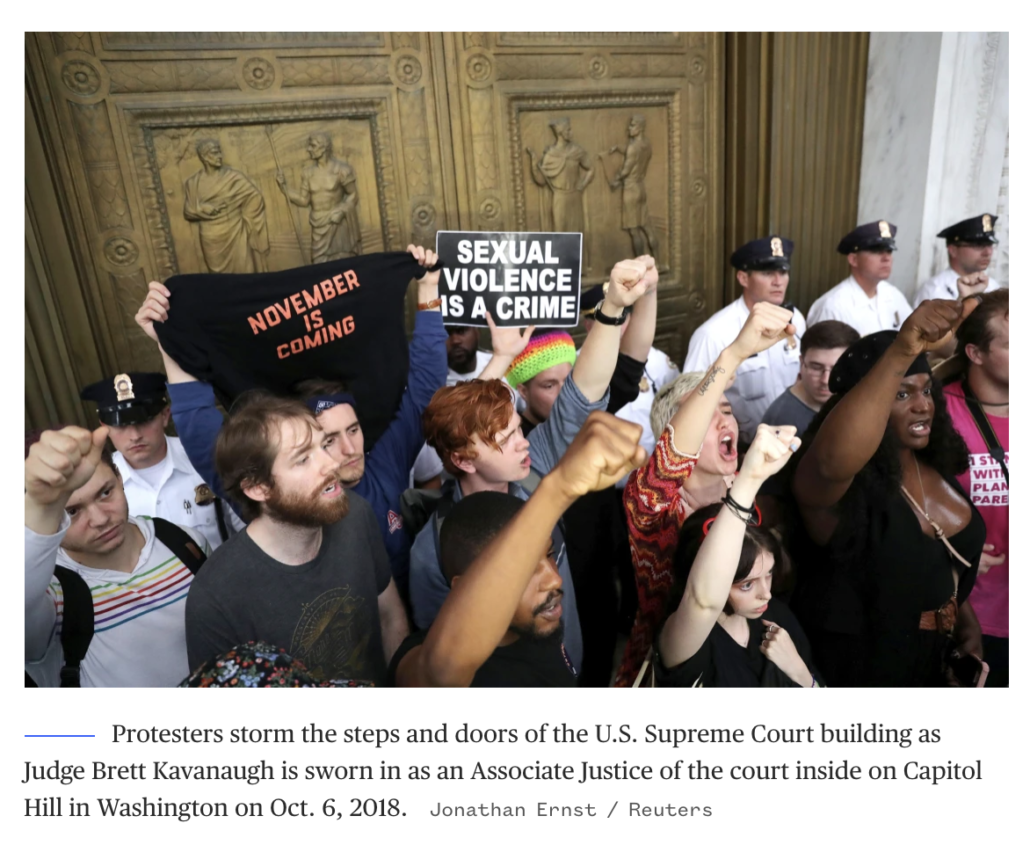

About two years before the January 6 events, in October 2018, Congress held confirmation hearings for now Justice Kavanaugh. Of course, confirmation hearings are not ceremonial functions like the Electoral College vote count but are rather inquiries held pursuant to Congress’s investigatory power. Subpoenas are issued, sworn testimony is given. See, e.g., United States v. Cisneros, 26 F. Supp. 2d 24, 38 (D.D.C. 1998). As on January 6, Vice President Mike Pence was present and presiding over the confirmation vote.4 Hundreds of protestors broke through Capitol Police barricades.5 They burst through Capitol doors and “stormed” the Senate chamber. N.Y.Times, Oct. 6, 2018. There, they disrupted and delayed the Senate proceedings by screaming and lunging toward the Vice President and other people. As a report described the day, Saturday’s vote reflected that fury, with the Capitol Police dragging screaming demonstrators out of the gallery as Vice President Mike Pence, presiding in his role as president of the Senate, calmly tried to restore order. “This is a stain on American history!” one woman cried, as the vote wrapped up. “Do you understand that?” N.Y. Times, Oct. 6, 2018. Here are some of the images of protestors who broke through Capitol Police barricades and entered Congress that day, about 26 months before January 6:

Roll Call, Oct. 6, 2018 (VP Pence presiding in Capitol Building)

NBC News, Oct. 6, 2018 (VP Pence presiding in Capitol Building)

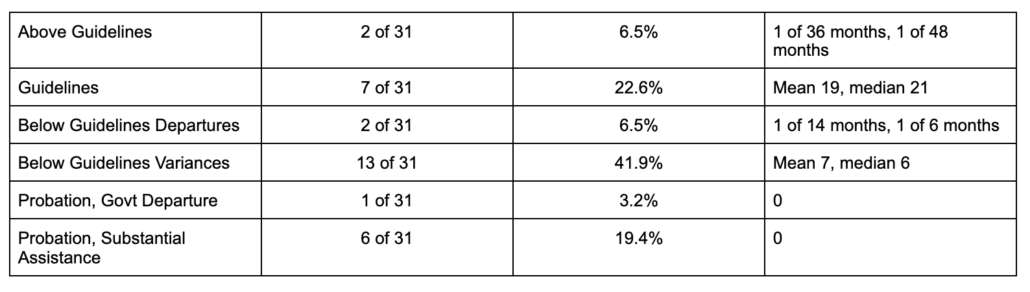

Though they intentionally delayed the congressional proceedings, these protestors, numbering in the hundreds, were not charged with “obstruction of Congress” under § 1512(c)(2). Certainly, if the lack of case law supporting the government’s interpretation of “official proceeding,” the absence of any legislative history pointing towards that interpretation, and the DOJ’s own internal inconsistent position do nothing to provide “fair notice” to an “ordinary person” that such political protests constitute “obstruction of official proceedings,” the fact that hundreds of protestors were charged with no offense at all for conduct for which the indictment here charges Nordean does not provide that notice either. Moreover, the naked charging disparity between the episodes—legally similar, according to the government here—also implicates the vagueness doctrine’s concern for arbitrary and discriminatory law enforcement enabled by vague, shifting standards that allow “prosecutors and courts to make it up,” particularly in the context of the rights of free speech, assembly and petitioning of the government. Dimaya, 138 S. Ct. at 1212 (Gorsuch, J., concurring); United States v. Davis, 139 S. Ct. 2319 (2019) (Gorsuch, J.) (residual clause of § 924(c) unconstitutionally vague); Johnson v. United States, 576 U.S. 591 (2015) (residual clause of Armed Career Criminal Act unconstitutionally vague).

4 Kavanaugh is sworn in after close confirmation vote in Senate, N.Y. Times, Oct. 6, 2018, available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/06/us/politics/brett-kavanaugh-supremecourt.html.

5 See, e.g., Kavanaugh protestors ignore Capitol barricades ahead of Saturday vote, Roll Call, Oct. 6, 2018, available at: https://www.rollcall.com/2018/10/06/kavanaugh-protesters-ignore[-]capitol-barricades-ahead-of-saturday-vote/.

[my italics]

Nordean is conflating two different things in an attempt to draw this parallel. There were the protestors who were in the actual hearing room, who briefly yelled and then were removed. And then there were protestors who broke through a barricade at the Capitol (there were also protestors who broke through a police line at the Supreme Court and knocked on the door). The “hundreds” of protestors Nodean mentions were watching from below and then were on the steps.

Protesters broke through Capitol Police barricades and rushed up the steps to the Capitol Rotunda Saturday afternoon amid large demonstrations ahead of a Senate vote on Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh.

The metal barricades were erected Thursday to keep demonstrators on specific areas of the Capitol grounds.

[snip]

As each batch of arrestees walked down the stairs, the cheers rose from the hundreds assembled below on the east front stretching out to the street.

In an effort to conflate the two, Nordean invented things that weren’t in the NYT story he claimed to rely on, both that the people inside the hearing had “stormed” the Senate chamber and that those protestors were “lunging” at the Vice President.

As a chorus of women in the Senate’s public galleries repeatedly interrupted the proceedings with cries of “Shame!,” somber-looking senators voted 50 to 48 — almost entirely along party lines — to elevate Judge Kavanaugh. He was promptly sworn in by both Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and the retired Justice Anthony M. Kennedy — the court’s longtime swing vote, whom he will replace — in a private ceremony.

[snip]

Republicans are now painting Democrats and their activist allies as angry mobs. Senator John Cornyn, Republican of Texas, delivered a speech on Saturday assailing what he called “mob rule,” while the majority leader, Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, told reporters that “the virtual mob that has assaulted all of us in this process has turned our base on fire.”

The bitter nomination fight, coming in the midst of the #MeToo movement, also unfolded at the volatile intersection of gender and politics. It energized survivors of sexual assault, hundreds of whom have descended on Capitol Hill to confront Republican senators in recent weeks.

[snip]

Saturday’s vote reflected that fury, with the Capitol Police dragging screaming demonstrators out of the gallery as Vice President Mike Pence, presiding in his role as president of the Senate, calmly tried to restore order. “This is a stain on American history!” one woman cried, as the vote wrapped up. “Do you understand that?”

The government makes some of these points in their surreply, notably pointing out that the protestors who actually interrupted the hearings were all legally present in the public gallery, and had all gone through security to get there.

Defendant’s attempts to manufacture a parallel between the criminal activity during confirmation hearings for Justice Kavanaugh and the events of January 6 should remain on the Internet—they do not fare well when included in a legal brief. Among the distortions of fact and law in his brief, Defendant claims that on October 6, 2018, protestors “burst through Capitol doors and ‘stormed’ the Senate chamber” during confirmation hearings for Justice Kavanaugh. That is not accurate.2 The confirmation hearings were public, and the gallery of the Senate Chamber was open to the public on the day of the vote to confirm Justice Kavanaugh. See C-SPAN, Final Confirmation Vote for Judge Brett Kavanaugh, Oct. 6, 2018 available at https://www.cspan.org/video/?452583-11/final-confirmation-vote-judge-brett-kavanaugh. Indeed, Vice President Pence twice reminded the “guests” in the Gallery that expressions of approval or disapproval were not permitted. Id. Protestors who demonstrated inside the Senate Chamber on October 6 did so after lawfully accessing the building and being subjected to security screening. 3 See, e.g., Public seating at Kavanaugh hearing cut in half, then restored again, PBS News Hour, Sept. 5, 2018, available at https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/public-seating-at-kavanaugh[-]hearing-cut-in-half. No serious parallel can be drawn between the two events.4

[snip]

3 Those entering the earlier confirmation hearings reportedly had to pass through multiple identification checks. Members of the public were required to “first wait in line outside the building to go through an initial screening” before being “escorted in small groups to a holding area outside the committee room itself.”

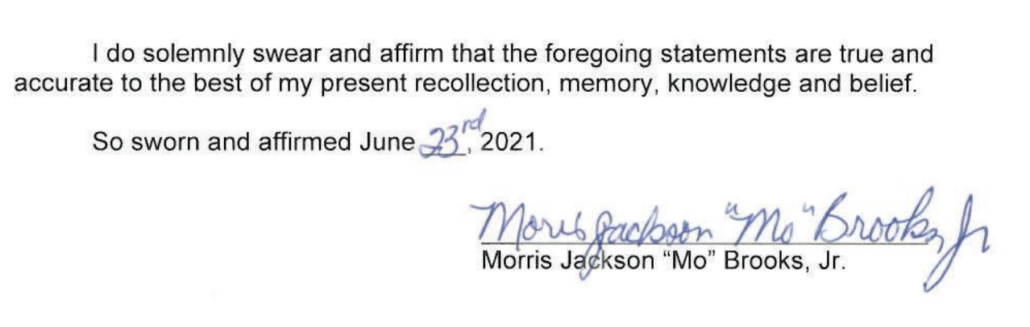

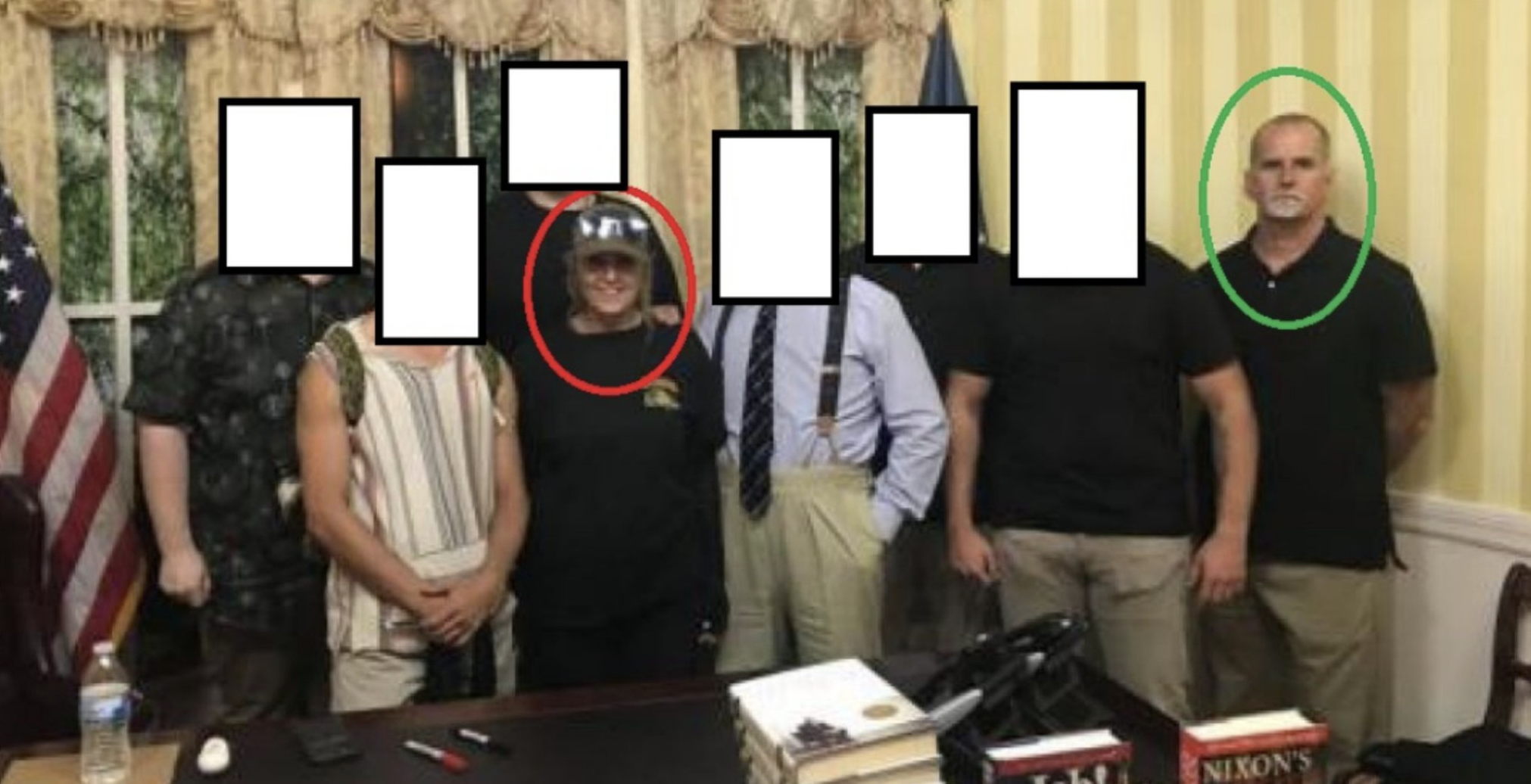

The government twice mocked Nordean for using the wrong pictures in his brief.

While Defendant can claim to have “images of protestors who broke through Capitol Police barricades and entered Congress” on October 6, 2018 (Id. at *14), the Court will immediately recognize that one of the images depicts protestors on the steps of the Supreme Court.

[snip]

2 In his Reply, Defendant included two pictures of protestors who had “stormed” the Capitol. The pictures alone underscore the frivolous nature of Defendant’s argument. But there is another problem—the protestors in the second photograph were on the steps of the Supreme Court.

It would be a great gotcha if it were true.

It’s not. While there were protestors that day at the Supreme Court, and while the story Nordean mistitles and doesn’t include a URL for does describe protestors storming past a police line on the Supreme Court stairs, the picture Nordean used was, indeed, from the Capitol steps.

Here’s what the view of those same steps looked like after mobsters occupied them on January 6 (from the NYT documentary on it); by this point several windows were already broken:

I can think of no instance where rioters who only occupied those East steps were even arrested (there were several people who occupied the more violent West Terrace who were arrested, most commonly in association with a conspiracy or assault charge), suggesting the equivalent January 6 “protestors” were in fact treated more leniently than the protestors — some of whom were arrested — from the Kavanaugh protests. For example, Proud Boy Ricky Willden may never have entered the building from the East stairs, but he is accused of spraying cops with some toxin.

Here’s what the protest at the Supreme Court looked like (again, from the same NBC article), with the caption that makes this incidence of “storming” seem quaint by comparison:

It’s an unbelievably embarrassing error to make — to accuse Nordean of an error when in fact the government was in error, especially while suggesting that Judge Kelly would immediately recognize the Supreme Court. All the more so given that Joe Biggs’ re-entry through the East door is charged in this indictment. Getting this wrong is a testament that the government didn’t spend as much thought responding to Nordean’s comparison as they need to, not just to rebut his argument, but to reflect seriously on what the line between the civil disobedience of the Kavanaugh hearings and the terrorist attack of January 6 is such that the former resulted in over a hundred misdemeanor arrests onsite whereas the latter resulted in delayed arrests and felony charges.

There are clear differences, differences that go beyond the fact that the entire Capitol was shut down on January 6 whereas (as the government notes) protestors were legally present when they interrupted the Kavanaugh hearing. There’s no evidence any of the Kavanaugh protestors were armed, whether with baseball bats or bear spray or guns. There were no reports that protestors assaulted police, much less continued to march past them after causing injuries that required hospitalization. Contrary to Nordean’s invention, protestors did not lunge at Pence, and certainly didn’t threaten to assassinate him. In general, protestors were more compliant upon arrest than January 6 rioters (which is one of many reasons why the police succeeded in arresting them, whereas several charged January 6 defendants escaped or were forced to be released by other rioters). While protestors definitely criticized Kavanaugh’s alleged actions (and his own screaming), I’m not aware of any who threatened to injure much less assassinate him onsite. The threats against Senators — most notably, Susan Collins — were electoral, not physical.

This surreply brief provided the government an opportunity to make that case, make it soberly, and make it in such a way to respond to legitimate questions that right wingers who aren’t aware of these real differences might raise. The surreply also provided the government an opportunity to explain why Neil Gorsuch won’t find this to be a charging disparity when he eventually reviews this challenge — because he almost certainly will, which is obviously why Nordean put that nod to Gorsuch right there in his brief. How do you screw something like that up???

But the government didn’t do that. Instead, in rebutting Nordean, the government tried to dick-wag. And failed, badly.

I’m tired of some of Ethan Nordean’s bullshit arguments myself. But the legal question about what makes the insurrection bad enough to treat its masterminds as terrorists is a very serious one, one that needs to be treated with more care than the government did here.

Update: I’ve updated the comparison image for the East stairs and added the observation that few if any January 6 protestors who only climbed the East stairs were charged.

Update: emptywheel gets results.

The United States files this notice of correction along with the refiling of its Surreply to Defendant Nordean’s Motion to Dismiss. In its original filing, the United States asserted that Defendant Nordean had misidentified a photograph of the protests on October 6, 2018. Such assertion was incorrect and has been removed from page 1 and footnote 2 of the corrected filing.