From emptywheel, 4/2: Thanks to the generosity of emptywheel readers we have funded Brandi’s coverage for the rest of the trial. If you’d like to show your further appreciation for Brandi’s great work, here’s her PayPal tip jar.

The Proud Boys seditious conspiracy trial started this week with prosecutors rolling out meticulous frame-by-frame video footage from Jan. 6 that, for the first time in more than a month of proceedings, painted the clearest picture yet of the extremist’s groups alleged coordinated efforts to stop the U.S. Congress from certifying the 2020 election.

But as soon as presentations of that compelling—and often damning—evidence and testimony had concluded, the already-slow-going trial was abruptly halted by revelations over a “spill” of potentially classified FBI communications inadvertently disclosed to the defense.

The materials first bubbled to the surface when Nick Smith, the defense counsel representing Proud Boy Ethan Nordean, began cross-examination of FBI Special Agent Nicole Miller, a lead case agent on the Proud Boys probe. Nordean is a former chapter leader of the neofascist network who is now facing seditious conspiracy charges alongside the group’s onetime ringleader Henry “Enrique” Tarrio and their self-proclaimed “western chauvinist” cohorts Joseph Biggs, Zachary Rehl, and Dominic Pezzola.

Miller had for two days testified to her painstaking review of police bodycam footage, closed-circuit surveillance video, and other media broadcasts from Jan. 6 as she and assistant U.S. Attorney Erik Kenerson neatly buttoned up some of the last pieces of evidence expected from the prosecution as they edge toward the end of their case-in-chief.

But once Smith began to cross-examine Miller with the aim of impeaching her credibility and potentially striking the gut punches of testimony and evidence she delivered this week, the attorney revealed that the prosecution had, in preparation for trial, turned over an Excel spreadsheet to the defense containing Miller’s communications with fellow FBI agents.

While by itself such production is standard for a criminal trial, that spreadsheet, Smith said, also happened to feature more than 1,000 “hidden” rows of Miller’s internal FBI messages, some related to the case, some not.

Crucially, some of those messages, Smith alleged, indicated that agents had improperly reviewed privileged attorney-client conversations between Nordean’s co-defendant, Zachary Rehl, and Rehl’s former attorney, the recently suspended Jonathan Moseley, while Rehl was in detention. One of the messages appeared to show an FBI agent telling Miller that Rehl, the former president of the Proud Boys Philadelphia chapter, was ready to fight looming charges at trial.

“Don’t freak out Jason and Luke yet,” the agent identified as T.J. Wang wrote to Miller.

“Jason” is believed to be assistant U.S. Attorney Jason McCullough, one of several attorneys working the Proud Boys seditious conspiracy case. “Luke” is believed to be Luke Matthews Jones, another attorney initially assigned to the investigation.

Another message that was sent to Miller and revealed in court read, “You need to go into that CHS [confidential human source] report you just put and edit out that I was present.”

Smith seized too onto a message sent to Miller by another agent assigned to a different case. The other agent recounted a directive that they had received from a higher-up about “destroy[ing] 338 items of evidence.”

Smith’s line of inquiry triggered objections from prosecutors immediately and on Wednesday, presiding U.S. District Judge Timothy Kelly abruptly stopped the cross-examination and dismissed jurors early so the parties could discuss the evidence. Once outside their presence, Kelly went back and forth over the messages’ relevance and scope. Rehl’s defense attorney, Carmen Hernandez, quickly raised the alarm about potential Sixth Amendment violations citing the alleged FBI review of Rehl’s jailhouse communications with his former attorney.

In short order, a chorus of motions for mistrial by the defense rang out.

Kelly was not immediately convinced the communications fell within the narrow scope of Miller’s testimony in court, since most if not all of her testimony revolved around the Proud Boy defendants’ movements on Jan. 6 and their communications. With three months of trial in earnest long underway, Kelly cautioned both parties to slow down and assess the path forward after returning to their “war camps or peace camps” for the night, he said.

By Thursday morning, assistant U.S. attorney Jocelyn Ballantine, who is overseeing the case against the Proud Boys, told Judge Kelly that the prosecution had not fully appreciated the complexity of the inadvertent exposure.

“It appears [some of our] Jencks production may include a spill of classified information,” Ballantine said before requesting the Justice Department receive a single day to complete a classification review of Miller’s materials and claw back any contents for national security purposes before the trial resumed.

Defense attorney Norm Pattis, who represents Joseph Biggs along with defense attorney Dan Hull, was adamant that the government’s oversight should rightfully be to their benefit. Without a court order, Pattis told Judge Kelly, he would not return any documents already in evidence and further, he would use them to vigorously defend his client. At the same time he made these pronouncements however, Pattis also conceded that as far as anyone knows, the messages at issues might be wholly unrelated to the Proud Boys case anyway. That included, he said, the communications about the destruction of evidence.

Nevertheless, Pattis still asked the judge to appoint an independent party or special master to conduct a classification review. His request was matched by Rehl’s attorney Carmen Hernandez though Hernandez insisted that much of the material appeared innocuous to her eye. As Hernandez began to read portions she deemed unclassified aloud in court—prompting all of the color to drain from Judge Kelly’s face—Ballantine stepped in.

Since Miller had already testified as a witness for the government on direct examination, the prosecution was now precluded from speaking to her about the case any further in private. By having Miller testify openly in court, Ballantine argued this would establish how Miller conducted her review without adding further delay to the trial or more overt exposure of sensitive information.

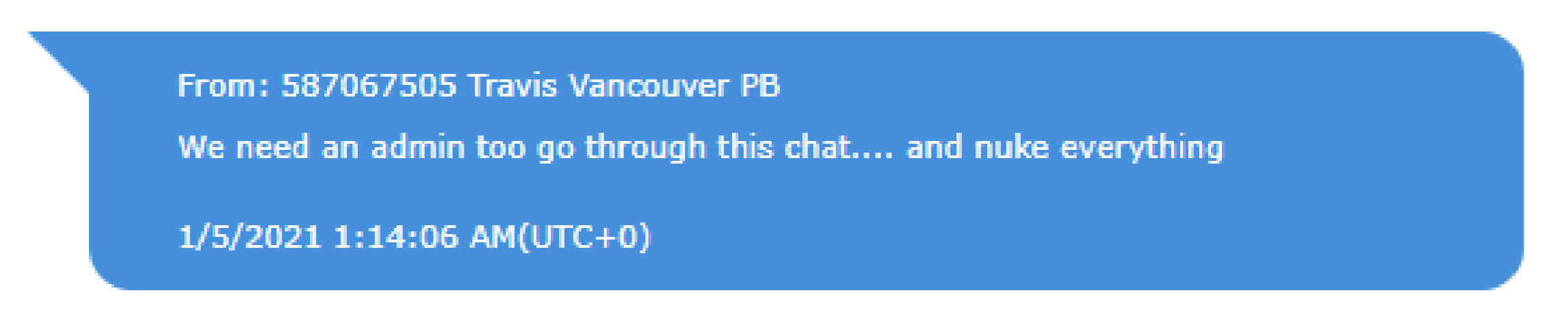

Returning to the stand but outside the view of the jury, Miller testified Thursday that she was ordered by FBI headquarters to go through a collection of her internal communications pulled from the FBI’s in-house messaging program known as Lync. She was to review messages from the period of Jan. 6, 2021, to Nov. 1, 2022, just before the originally anticipated start date of the Proud Boys trial. That final compilation was then to go to prosecutors at the U.S. Attorney’s Office who could pore over it before passing it off to the defense for discovery.

The special agent said she pulled somewhere between 12,000 to 15,000 lines of information. That would make up thousands of rows, but what she remitted to prosecutors ultimately included 25 to 26 rows. The rest of the rows, it would seem, were hidden through what prosecutors initially described as a possible glitch in the spreadsheet but the exact reason was not made clear in court this week. As a result, Ballantine was equally uncertain about whether Miller had conducted the review of only her messages in the dataset or if Miller had conducted a review of all the messages—including those rows now hotly in the defendant’s possession.

The distinction was key, and Ballantine, unfortunately for the Justice Department, elicited that Miller had not reviewed those messages for classification purposes.

“The FBI needs to conduct that review and this information will allow us to conduct [it]. I understand it would appear to counsel that some of these Lync messages appear not to be classified and that is correct, but the FBI needs to conduct, consistent with its national security obligations, that review,” she said. “I would ask that counsel be instructed by the court not to further review the spreadsheets, and not to send them to anyone else while the FBI conducts a classification review of messages sent by other people in that spreadsheet.”

Judge Kelly agreed, orally issued the order, and left the evidence in the defense’s hands. The matter will be picked up on Monday.

This interruption to the pace of the trial is but the latest in a long series of fits and starts that have pockmarked proceedings from the beginning. The trial was meant to begin last August but openings were delayed by the judge in light of the Jan. 6 committee’s release of its final report and transcripts at the end of last summer. The start date was then moved to December and jury selection alone took almost two weeks as parties questioned a pool of 150 prospects before the group was whittled down to 16 jurors including alternates.

More than a dozen requests were filed by the Proud Boys to change venues and before finally beginning the historic trial, defense counselors Nick Smith and Carmen Hernandez both threatened to withdraw from the case altogether when dissatisfied with some of Judge Kelly’s early evidentiary rulings. Biggs’ attorney Norm Pattis was nearly thrown off the case completely when he was suspended from practicing law for six months after his botched handling of sensitive documents for client Alex Jones in Jones’ Sandy Hook defamation case. Pattis appealed and his suspension was postponed. Given the months of delays up to that point, Kelly allowed Pattis to represent Biggs, recognizing the hardship of bringing a new attorney into the fold at such a late hour. Not helping matters any further was a potential conflict of interest that arose with Biggs’ only other attorney at the time, Dan Hull. Just days before the trial was to finally begin in January, Hull informed the court that he had contacted Proud Boy Jeremy Bertino—who ultimately flipped on Tarrio and pleaded guilty to seditious conspiracy —long before the trial began. Hull had talked to Bertino about possibly representing him. As a result, only Pattis was able to cross Bertino. Roger Roots, the defense attorney for defendant Dominic Pezzola, only signed onto the case a day before opening statements.

Once finally underway, evidence from the prosecution trickled out at a snail’s pace with testimony from key witnesses often stilted by a steady barrage of objections from the defense about the admissibility of evidence including evidence both parties had already agreed to admit pretrial. Crosstalk and bickering among attorneys or with Judge Kelly has often led the judge to call for lengthy sidebars, sometimes forcing him to excuse jurors from the courtroom as matters are resolved. There have been several days where jurors were not admitted inside the courtroom for more than an hour as infighting over evidence or witness testimony was aired out at the top of a trial day.

As of February 28th, there had been no less than a dozen calls for mistrial by the defense.

So common was this practice that last month, with his tone dripping in incredulity, Judge Kelly remarked to attorneys “it wouldn’t be a day in this trial without a mistrial motion.”

Two former Proud Boys who pled guilty and agreed to cooperate with the government, Jeremy Bertino and Matthew Greene, had already testified long before Agent Miller took the stand this week and the classification issue exploded.

They, and in particular, Bertino, were considered star witnesses for the prosecution and it is very likely that their testimony failed to leave the defendants altogether unscathed in the eyes of the jury.

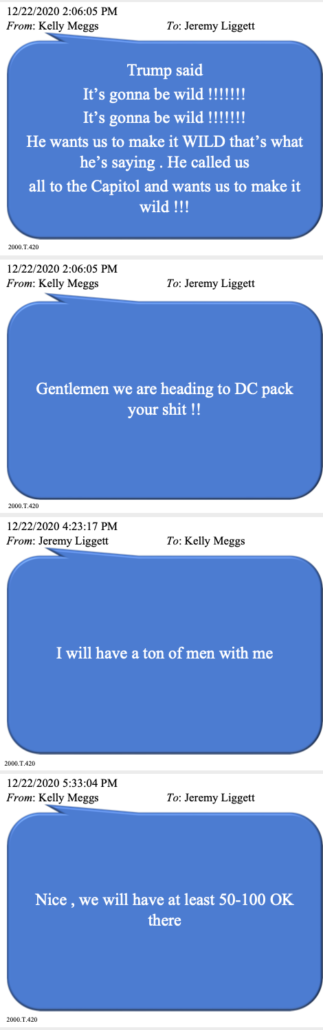

Bertino said after Trump namedropped Proud Boys at the 2020 presidential debates and told them to ‘stand back and stand by,’ the extremist group’s recruitment efforts surged. The Proud Boys and a new world of prospective members were whipped into a frenzy, he said. Proud Boys were regularly hanging on Trump’s every word as he launched one failed legal bid after another to declare the 2020 election results fraudulent. Once the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Trump’s forays, desperation among Proud Boys grew, Bertino said and members and leaders alike, including Tarrio, became singularly focused on the necessity of an “all-out revolution.”

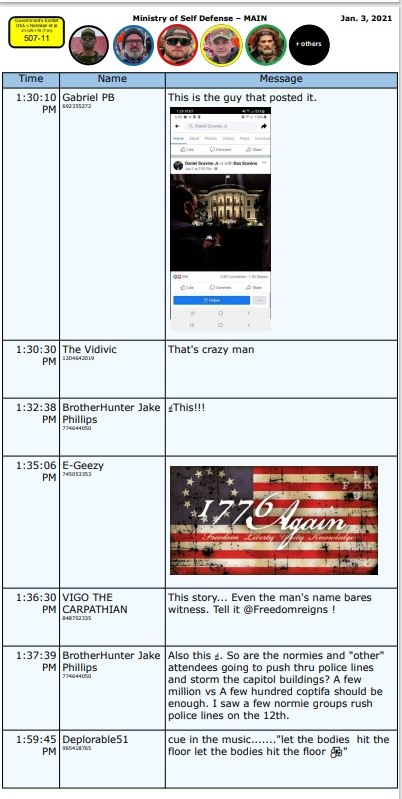

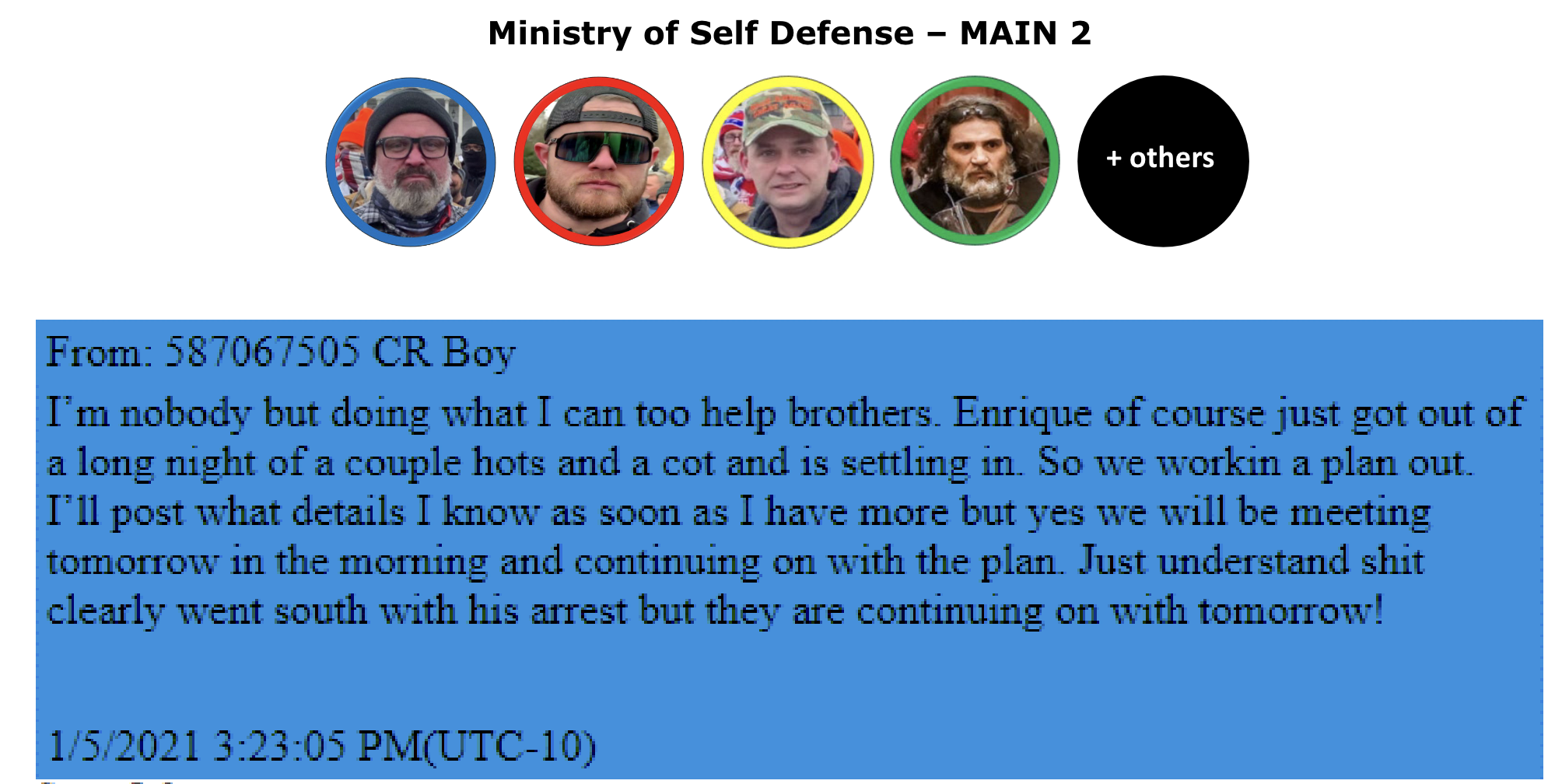

What followed was the creation of the group’s Ministry of Self-Defense, a channel, Bertino said, where members would discuss operations for Jan. 6 in code. Prior to that, Greene, who traveled to D.C. on Jan. 5 with Proud Boy William Pepe—Dominic Pezzola traveled with Greene and Pepe too but rode in another vehicle—told jurors that on the eve of the insurrection, he was added to a chat called “Boots on Ground.”

“I was led to believe it was some sort of coordination group for Proud Boys in D.C. for the 6th,” he said.

Greene revealed that he wasn’t privy to specific plans but was instructed to program handheld radios for any Proud Boys who might want them the night before the attack. And when the moment finally arrived and Greene found himself standing before the first barrier that was breached at the Capitol, he told jurors he thought to himself: “Oh shit, this is it.”

“I personally had an abstract feeling that Proud Boys were about to be a part of something,” Greene said before calling the group the “tip of the spear” on Jan. 6.

But, he added, “I never heard specifically what that could be. But as people moved closer to the Capitol, I was in the moment, putting two and two together and saying [to myself] ‘well, here it is,” Greene testified on Jan. 24.

Before Miller testified, Bertino and Greene’s testimony allowed prosecutors to introduce some of the raw and wildly anti-democratic, pro-authoritarian discourse among Proud Boys. Their testimony also exposed evidence of the group’s reliance on frequent communication by way of Telegram, Parler, or teleconference meetings and they helped demonstrate to jurors how Proud Boys were siloed by leadership status or divvied up on a need-to-know basis.

And underpinning all of this was evidence supporting the government’s core legal theory about the Proud Boy defendants and Jan. 6: They didn’t act alone in order to stop the certification by force, they relied not just on themselves but on what the government has dubbed “the tools of the conspiracy.”

The theory, in sum, suggests the following: to pull off a stop to the certification and potentially keep Donald Trump in the White House despite his defeat, defendants relied not just on individuals who were part of the alleged conspiracy but they would rely on inciting and rallying people unconnected to the organization, too. Bertino and others, chats in evidence have shown, referred to these potential allies as “normies.”

“Normies,” Bertino told jurors, were anyone who supported Trump or considered themselves “right of center” politically. They were “everyday people,” Bertino testified on Feb. 27, who would get behind Proud Boys because they shared the same beliefs about the “stolen” election and the perilous future America faced.

Early in the morning on Jan. 6, in the “New Ministry of Self Defense” chat as Bertino spoke to two Proud Boys, Aaron Wolkind and John Stewart about the day ahead in Washington, Wolkind said he wanted to see “thousands of normies burn that city to ash today.”

Stewart prayed, “God let it happen” before lamenting that “normiecons have no adrenaline control” and were like a “pack of wild dogs.”

Bertino replied: “Fuck it let them loose.”

Charles Donohoe, who would later plead guilty to conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding and assaulting police, told Wolkind, Stewart, and Bertino right around the same time in that same chat that he was already “hoofing it” to the Washington Monument with a crew of 15. They weren’t wearing their recognizable Proud Boy black and yellow colors, either, Donohoe said.

Tarrio, prosecutors showed jurors, had instructed them not to days before.

Despite the intimate nature of the testimony delivered by Bertino and Greene, it arguably was not until Kenerson elicited Agent Miller’s testimony this week that the full punch of the prosecution’s “tools” theory was delivered.

With Miller as a guide, for two consecutive days, video footage was shown to jurors, often frame by frame or motion by motion, of the tinder keg that Proud Boys tapped on Jan. 6.

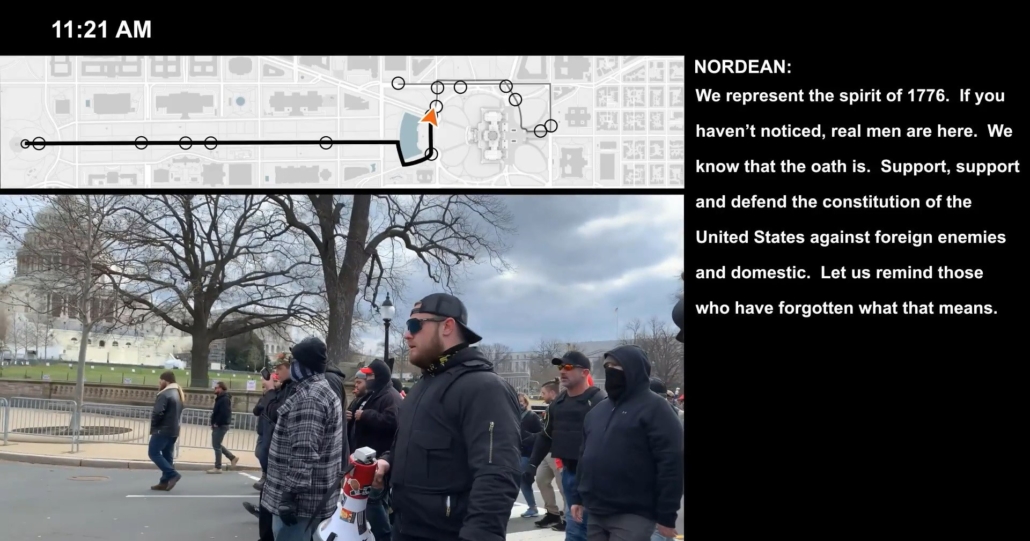

Using aerial surveillance footage from the Capitol, Miller used her finger to circle on a screen shared with jurors precisely where Proud Boys positioned themselves on Jan. 6.

The crowd, standing shoulder to shoulder, is on the precipice of making history whether they know it or not. And there, at the very front of the horde of Trump’s supporters, Miller drew nine circles, each representing multiple individuals, including Proud Boys, grouped together. Four of the nine group circles were situated as close as possible to a police barricade line. The others stood just behind them. The groups were evenly spaced and evenly numbered. It was just about 1 p.m. Then-Vice President Mike Pence was still minutes away from making his announcement that he would not decertify slates unilaterally.

Miller, and other witnesses for the government, including Bertino, have testified that Proud Boys never even bothered to listen to Trump’s speech on the morning of the 6th.

They gathered at predetermined meeting points, like at the Washington Monument, and marched down to the Capitol picking up speed and allies—the ‘tools’ they needed for blunt force—as they went.

Miller reviewed video footage in court this week showing Joseph Biggs, for example, pointing a group of Proud Boys including Donohoe, Gilbert Fonticoba, and Eddie Block, away from the area where Trump was speaking at the Ellipse and toward the Capitol.

“Come up over here and then roll through,” Biggs’ is heard saying in one video clip, Miller testified.

Biggs riled up the crowd as he marched on the Capitol, Miller said, chanting “fuck antifa” or “we love Trump” or “1776.”

Miller showed jurors footage too of the moment when Ryan Samsel, who is not a Proud Boy, approached an already keyed-up Biggs and wrapped his arm around him. Biggs didn’t throw Samsel’s arm off. They would speak briefly and within moments, Samsel, Miller said, could be seen removing his jacket as if to fight police. As barriers first begin to fall, Agent Miller testified that she was able to identify defendant Zachary Rehl screaming “Fuck them! Storm the Capitol!”

The agent testified that it wasn’t until Proud Boys showed up at the Peace Monument, located just in front of the Capitol, that the crowd’s tenor had changed. Footage showed they were “relatively peaceful,” until then, Miller testified.

When Nordean arrived at the Peace Monument, he grabbed a bullhorn and told a gathering crowd: “We represent the spirit of 1776.” He promised, “real men are here,” and discussed Constitutional oaths against enemies foreign and domestic.

“Let us remind those who have forgotten what that means,” Nordean said.

In other footage, members like Daniel “Milkshake” Lyons Scott were spotted meeting with Proud Boys at the Monument before later separating and then rejoining each other at police lines.

“Milkshake” was standing alongside key members of the conspiracy like Charles Donohoe, as the men prepared to storm the Capitol. Never far from them, Miller added, were Dominic Pezzola, Matthew Greene, William Pepe, and others. Seconds after the mob began ascending stairs to the Capitol’s interior, Agent Miller said it was Biggs, Fonticoba, and a handful of others, like Shannon Rusch and Trevor McDonald who joined him.

In one clip shown to the jury, as Proud Boys make hand signals affiliated with the white power movement to each other as they lay siege, Christopher Worrell, a Proud Boy with ties to Roger Stone, appears on screen and shouts: “Yeah! Taking the Capitol!”

Nordean, Miller said, had gathered “tools” of the conspiracy like Paul Rae and Arthur Jackman and others as they advanced past barriers or up the Capitol stairs and balustrades toward the interior.

It was Jackman and another member from the marching group, the FBI agent testified, who used turned-over bike rack barriers as makeshift ladders to help scale the walls. Biggs would scale the “ladder” with Fonticoba and Rae.

When the men reached the upper west plaza, where some of the worst violence would occur, Miller testified that it wouldn’t be long before Pezzola was striding into the same location with a stolen police riot shield in tow. Jurors watched footage frame by frame of Pezzola smashing open a window. When one pane wouldn’t break, he tried the one next to it and successfully “unattached” the window from its frame completely, Miller said.

Pezzola was the fifth or sixth person inside after that. He let other rioters stream through first. Minutes later, Biggs, Rae, and Fonticoba would come through a busted door in the same hallway that Pezzola entered. Jurors watched Pezzola stalk that hallway and as Miller testified, Pezzola would later appear to hold a radio up to his head to talk to someone before taking off down a hallway to the Capitol crypt.

Rehl, meanwhile, she said, had made his way to the upper west terrace and was joined by Rae and others like Isaiah Giddings, Brian Healion, and Freedom Vy. Tarrio wasn’t on Capitol grounds on Jan. 6 but he was attuned to what was happening at the Capitol anyway.

“I’m enjoying the show,” Tarrio wrote on Parler around 2:35 p.m. “Do what must be done. #WeThePeople.”

Three minutes later, as the surge was in full swing, Tarrio would bark on Parler: “Don’t fucking leave” and “Proud of my boys and my country.”

Tarrio and Bertino were texting privately at the same time, Miller said.

When Bertino, flushed with pride, told Tarrio, “Brother, you know we made this happen,” Tarrio responded with two words: “I know.”

When talking to fellow Proud Boy Chris Cannon over text that afternoon, Tarrio agreed when Cannon asked if the Proud Boys were a militia now.

“Yup,” Tarrio wrote.

“Make no mistake, we did this,” he added.

Cannon then sent a short video to Tarrio in the elders-only Skull and Bones chat. The video featured, among other things, footage from World War II including marching Nazis and victorious Nazis being saluted by Hitler. There were no objections made by the defense when the video was first played for the jury this week. It was also not the first time jurors would see Proud Boys reference Nazis.

During a chat with Biggs and other Proud Boys days before the Capitol attack, as Tarrio discussed how to avoid detection by wearing colors other than their traditional black and yellow garb, the national leader of the fascist organization seemed to outright tickle himself at one point.

“Did I just Goebbels this thing?” Tarrio said, referencing Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi minister of propaganda.

Defense attorneys claimed this week that the impact of the prosecution sharing the video Tarrio received from Cannon was too burdensome to bear. Smith said it was “designed to poison the well” against the defendants and that this case had “nothing to do with marching Nazis and brownshirts.”

Attorneys for all of the defendants insisted the prosecution unfairly included the clip and it should have been something the defense was alerted to in advance. Calls for mistrial by the defense began to billow from every corner but Judge Kelly denied them all.

“Let’s have a rule going forward that if it involves Nazis, you will tell me in advance,” the judge said.

He would agree to strike the video from the record and later instructed jurors that the footage depicting Nazis was not sent by Tarrio or any other defendant in the case.

Proceedings resume on Monday and the prosecution is expected to bring out just a few more witnesses before the defense takes over. It is expected that Tarrio and Biggs will testify on their own behalf.