There Were Two Dick-Waggings Directed at Iran This Week

By all appearances President Trump casually released highly classified information yesterday, as he has done repeatedly in the past.

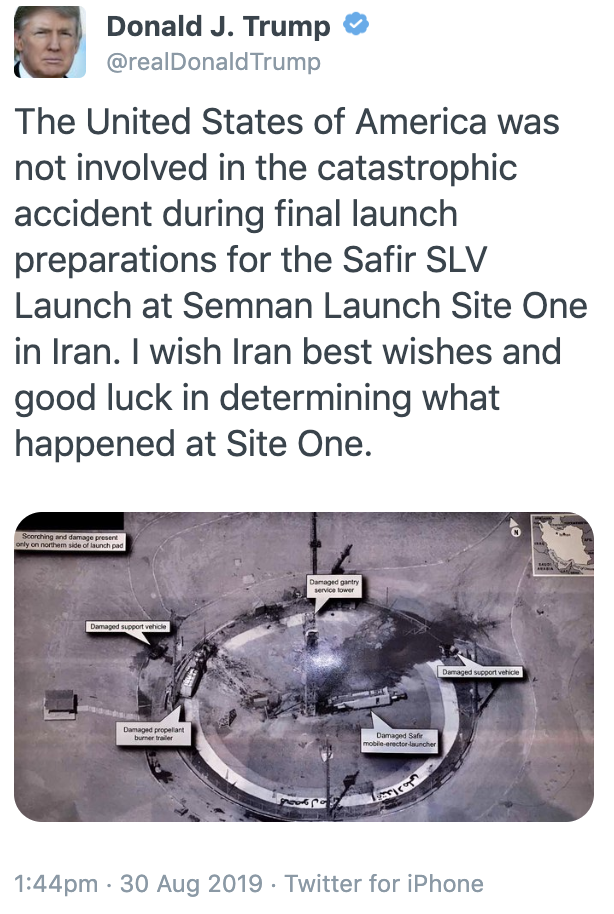

Within hours of this tweet, CNBC confirmed that this image comes from one of Trump’s intelligence briefings, which led experts to assume Trump had been careless.

A U.S. defense official told CNBC that the picture in Trump’s tweet, which appeared to be a snapshot of a physical copy of the satellite image, was included in a Friday intelligence briefing.

[snip]

But the quality of the photograph quickly raised the eyebrows of national security experts, who say that images this clear are rarely made public.

“I’m not supposed to see stuff this good. He’s not supposed to share it. I’ve honestly never seen an image this sharp,” said Melissa Hanham, deputy director of the Open Nuclear Network and director of the Datayo Project at the One Earth Future Foundation.

Hanham suspected the shot was taken from a high-altitude aerial vehicle using tracking technology, such as an RC-135S Cobra Ball or a similar aircraft.

“This will have global repercussions,” said Joshua Pollack, a nuclear proliferation expert and editor of the Nonproliferation Review.

“The utter carelessness of it all,” Pollack said. “So reckless.”

Even before the NYT weighed in last night, I had my doubts whether this was reckless, or whether it was a calculated decision to dick-wag over the sabotage of a missile program the Iranians deny.

First, the tweet was almost certainly not written by Trump. It has no grammatical errors or typographical anomalies. It uses technical terms and consists of full sentences.

In other words, the tweet has none of the hallmarks of Trump’s reflexive tweeting. Someone helped him tweet this out.

Then there’s the fact that, earlier this week, the US dick-wagged about another successful operation against Iran, a cyberattack that took out the IRGC database that they were using to target western shipping.

The head of United States Cyber Command, Army Gen. Paul M. Nakasone, describes his strategy as “persistent engagement” against adversaries. Operatives for the United States and for various adversaries are carrying out constant low-level digital attacks, said the senior defense official. The American operations are calibrated to stay well below the threshold of war, the official added.

The strike on the Revolutionary Guards’ intelligence group diminished Iran’s ability to conduct covert attacks, said a senior official.

The United States government obtained intelligence that officials said showed that the Revolutionary Guards were behind the limpet mine attacks that disabled oil tankers in the Gulf in attacks in May and June, although other governments did not directly blame Iran. The military’s Central Command showed some of its evidence against Iran one day before the cyberstrike.

[snip]

The database targeted in the cyberattacks, according to the senior official, helped Tehran choose which tankers to target and where. No tankers have been targeted in significant covert attacks since the June 20 cyberoperation, although Tehran did seize a British tanker in retaliation for the detention of one of its own vessels.

Though the effects of the June 20 cyberoperation were always designed to be temporary, they have lasted longer than expected and Iran is still trying to repair critical communications systems and has not recovered the data lost in the attack, officials said.

Officials have not publicly outlined details of the operation. Air defense and missile systems were not targeted, the senior defense official said, calling media reports citing those targets inaccurate.

In the aftermath of the strike, some American officials have privately questioned its impact, saying they did not believe it was worth the cost. Iran probably learned critical information about the United States Cyber Command’s capabilities from it, one midlevel official said.

That story described the views of CyberCommand head General Nakasone, who did some dick-wagging in February over CyberCommand’s role in thwarting Russia’s efforts to tamper in the elections.

Whatever else Nakasone has done with his command, he seems to have made a conscious decision that taking credit for successful operations adds to its effectiveness. There certainly was some debate, both within the NYT story and in discussions of it, whether he’s right. But Nakasone is undoubtedly a professional who, when stories boasting of successful CyberCommand operations get released, has surely thought through the implications of it.

But as I said, last night NYT weighed in on the destroyed missile launch, with a story by long-standing scribes for the intelligence community, David Sanger and William Broad and — listed at the end in the actual story but given equal billing in Sanger’s tweet of it — Julian Barnes, the guy who broke Nakasone’s dick-wagging earlier in the week. It’s a funny story — as it was bound to be, given that virtually no one reported on the explosion itself and while this spends a line doing that, it’s really a story exploring what kind of denial this is.

Trump Denies U.S. Responsibility in Iranian Missile Base Explosion

[snip]

As pictures from commercial satellites of a rocket’s smoking remains began to circulate, President Trump denied Friday on Twitter that the United States was involved.

[snip]

Mr. Trump also included in his tweet a high-resolution image of the disaster, immediately raising questions about whether he had plucked a classified image from his morning intelligence briefing to troll the Iranians. The president seemed to resolve the question on Friday night on his way to Camp David when he told reporters, “We had a photo and I released it, which I have the absolute right to do.”

There is no denying that, even if it runs the risk of alerting adversaries to American abilities to spy from high over foreign territory. And there is precedent for doing so in more calculated scenarios: President John F. Kennedy declassified photographs of Soviet missile sites during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, and President George W. Bush declassified pictures of Iraq in 2003 to support the faulty case that Saddam Hussein was producing nuclear and chemical weapons.

[snip]

Mr. Trump’s denial and the satellite image he released seemed meant to maximize Iran’s embarrassment over the episode.

[snip]

If the accident was linked to a covert action by the United States — one that Mr. Trump would have been required to authorize in a presidential “finding” — he and other American officials would be required by law to deny involvement.

The laws governing covert actions, which stretch back to the Truman administration, focus on obscuring who was responsible for the act, not covering up the action itself. Most American presidents have fulfilled that requirement by staying silent about such episodes, but Mr. Trump does not operate by ordinary rules — and may have decided that an outright denial was his best course. [my emphasis]

Not everyone agrees with the claim that Trump would be required by law to deny a covert operation. He’s the President. He can do what he wants with classified information.

That said, the story may be an attempt to use official scribes to reframe this disclosure to make it closer to the way the intelligence community likes to engage in plausible deniability, with a lot of wink wink and smirking. Amid all the discussion of deny deny deny, after all, the NYT points to several pieces of evidence that this explosion was part of a successful program to sabotage Iran’s missile capabilities.

Two previous attempts at launching satellites — on Jan. 15 and on Feb. 5 — failed. More than two-thirds of Iran’s satellite launches have failed over the past 11 years, a remarkably high number compared with the 5 percent failure rate worldwide.

[snip]

It was the third disaster to befall a rocket launching attempt this year at the Iranian space center, a desert complex east of Tehran named for the nation’s first supreme leader. The site specializes in rocket launchings meant put satellites into orbit.

Tehran announced its January rocket failure but said nothing the one in February that was picked up by American intelligence officials. It has also said nothing officially about Thursday’s blast. Like many closed societies, Iran tends to hide its failures and exaggerate its successes.

The NYT also helpfully links earlier stories on on Iran’s missile program, including one from February by Sanger and Broad that states as fact that the US has accelerated a program to sabotage Iran’s missile program.

The Trump White House has accelerated a secret American program to sabotage Iran’s missiles and rockets, according to current and former administration officials, who described it as part of an expanding campaign by the United States to undercut Tehran’s military and isolate its economy.

Officials said it was impossible to measure precisely the success of the classified program, which has never been publicly acknowledged. But in the past month alone, two Iranian attempts to launch satellites have failed within minutes.

Those two rocket failures — one that Iran announced on Jan. 15 and the other, an unacknowledged attempt, on Feb. 5 — were part of a pattern over the past 11 years. In that time, 67 percent of Iranian orbital launches have failed, an astonishingly high number compared to a 5 percent failure rate worldwide for similar space launches.

Every astute reader who read the earlier Sanger and Broad story would have assumed this explosion was part of the American operation they described. Trump’s tweet would not have changed the extent to which the US could plausibly deny its sabotage operation.

Which means, among all the coyness and winking, this is the most interesting line of the NYT story.

It was unclear if Mr. Trump was using the explosion and the lurking suspicions among Iranians that the United States was again deep inside their nuclear and missile programs to force a negotiation or to undermine one.

Not discussed, however, is the other risk to Trump’s tweet: it has effectively given Iran and our other adversaries a sense of what kind of imagery capabilities we’ve got. That’s what some of the proliferation experts are most troubled by, the possibility that by tweeting out the image, Trump will make it easier for others to evade our surveillance.

But that should be discussed in the same breath as the earlier dick-wagging. While Iran surely suspected the database strike was US work, the earlier NYT story confirms it.

Yes, it’s clear that Trump’s tweet yesterday was dick-wagging. But so was the earlier report on the database hack. So this could reflect a broader change in the US approach to deniability.