The Significance of the James Wolfe Sentence for Mike Flynn, Leak Investigations, and the Signal Application

Yesterday, Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson sentenced former SSCI head of security James Wolfe to two months in prison for lying to the FBI. In her comments announcing the sentence, Jackson explained why she was giving Wolfe a stiffer sentence than what George Papadopoulos and Alex van der Zwaan received: because Wolfe had abused a position of authority.

“This court routinely sentences people who come from nothing, who have nothing, and whose life circumstances are such that they really don’t have a realistic shot of doing anything other than committing crimes,” Jackson said. “The unfortunate life circumstances of those defendants don’t result in a lower penalty, so why should someone who had every chance of doing the right thing, a person who society rightly expects to live up to high moral and ethical standards and who has no excuse for breaking the law, be treated any better in this regard.”

[snip]

Wolfe’s case was not part of special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, but the judge compared his situation to two defendants in the Mueller probe who also pleaded guilty to making false statements — former Trump campaign adviser George Papadopoulos, who spent 12 days in prison, and Dutch lawyer Alex van der Zwaan, who was sentenced to 30 days. Jackson concluded that Wolfe’s position as head of security for the Intelligence Committee was an “aggravating” factor.

The public shame he had endured, and the loss of his job and reputation, were not punishment enough, the judge said, but were rather the “natural consequence of having chosen to break the law.”

“You made blatant false statements directly to FBI agents who questioned you about matters of significance in the context of an ongoing investigation. And if anything, the fact that you were a government official tasked with responsibility for protecting government secrets yourself seems to make you more culpable than van der Zwaan and Papadopoulos, who held no such positions,” Jackson said.

While the resolution of this case is itself notable, it has likely significance in three other areas: for Mike Flynn, for DOJ’s leak investigations, and for encrypted messaging apps.

Emmet Sullivan will cite this sentence as precedent

It’s still far from clear that Emmet Sullivan will be sentencing Mike Flynn three months from now. Given Trump’s increasingly unstable mood, Flynn might get pardoned. Or, Flynn might try to judge shop, citing Sullivan’s invocation of treason Tuesday.

But if Sullivan does eventually sentence Flynn and if he still feels inclined to impose some prison time to punish Flynn for selling out his country, he can cite both this sentence and the language Jackson used in imposing it. Like Wolfe, Flynn occupied a (arguably, the) position of great responsibility for protecting our national security. Sullivan seems to agree with Jackson that, like Wolfe, Flynn should face more consequences for abusing the public trust. So Wolfe’s sentence might start a countertrend to the David Petraeus treatment, whereby the powerful dodge all responsibility.

(Note, this is a view that Zoe Tillman also expressed yesterday.)

DOJ may rethink its approach to using false statements to avoid the difficulties of leak cases

I have zero doubt that DOJ prosecuted Wolfe because they believe he is Ellen Nakashima’s source for the story revealing that Carter Page had been targeted with a FISA order, which is how they came to focus on him in the first place. But instead of charging him with that, they charged him for lying about his contacts with Nakashima, Ali Watkins, and two other journalists (and, in their reply to his sentencing memo, made it clear he had leaked information to two other young female national security reporters). In the sentencing phase, however, the government asked for a significant upward departure, a two year sentence that would be equivalent to what he’d face if they actually had proven him to be Nakashima’s source.

While the government provided circumstantial evidence he was Nakashima’s source — in part, her communications to him in the aftermath of the story — he convincingly rebutted one aspect of that claim (a suggestion that she changed her email footer to make her PGP key available to him). More importantly, he rightly called out what they were doing, trying to insinuate he had leaked the FISA information without presenting evidence.

The government itself admitted no fewer than four times in its opening submission that it found no evidence that Mr. Wolfe disclosed Classified Information to anyone. See infra Part I.A. Nonetheless, the government deploys the word “Classified” 58 times in a sentencing memorandum about a case in which there is no evidence of disclosure of Classified Information—let alone a charge.

[snip]

The government grudgingly admits that it lacks evidence that Mr. Wolfe disclosed Classified Information to anyone. See, e.g., Gov. Mem. at 1 (“although the defendant is not alleged to have disclosed classified information”); id. at 6 (“notwithstanding the fact that the FBI did not uncover evidence that the defendant himself disclosed classified national security information”); id. at 22 (“[w]hile the investigation has not uncovered evidence that Wolfe disclosed classified information”); id. at 25 n.14 (“while Wolfe denied that he ever disclosed classified information to REPORTER #2, and the government has no evidence that he did”).

The Court should see through the government’s repetition of the word “Classified” in the hope that the Court will be confused about the nature of the actual evidence and charges in this case and sentence Mr. Wolfe as if he had compromised such information.1

1 Similarly, the government devotes multiple pages of its memorandum describing the classified document that Mr. Wolfe is not accused of having disclosed. And although the government has walked back its initial assertion that Mr. Wolfe “received, maintained, and managed the Classified Document” (Indictment ¶ 18) to acknowledge that he was merely “involved in coordinating logistics for the FISA materials to be transported to the SSCI” (Gov. Mem. at 10), what the government still resists conceding is the fact that Mr. Wolfe had no access to read that document, let alone disclose any part of it. Beyond providing an explanation of how the FBI’s investigation arose, that document has absolutely no relevance to Mr. Wolfe’s sentencing, but it and its subject, an individual under investigation for dealings with Russia potentially related to the Trump campaign, likely have everything to do with the vigor of the government’s position.

It’s unclear, at this point, whether the government had evidence against Wolfe but chose not to use it because it would have required imposing on Nakashima’s equities (notably, they appear to be treating Nakashima with more respect than Ali Watkins, though it may be that they only chose to parallel construct Ali Watkins’ comms) and introduce classified evidence at trial. It may be that Wolfe genuinely isn’t the culprit.

Or it may be that Wolfe’s operational security was just good enough to avoid leaving evidence.

Whatever it is, particularly in a culture of increasing aggressiveness on leaks, the failure to get Wolfe here may lead DOJ to intensify its other efforts to pursue leakers using the Espionage Act.

DOJ might blame Signal and other encrypted messaging apps for their failure to find the Carter Page FISA culprit

And if DOJ believes they couldn’t prove a real case against Wolfe because of his operational security, they may use it to go after Signal and other encrypted messaging apps.

That’s because Wolfe managed to hide a great deal of his communications with journalists until they had sufficient evidence for a Rule 41 warrant to search his phone (which may well mean they hacked his phone). Here’s what it took to get Wolfe’s Signal texts.

Once the government discovered that Wolfe was dating Watkins, they needed to find a way to investigate him without letting him know he was a target, which made keeping classified information particularly difficult. An initial step involved meeting with him to talk about the leak investigation — purportedly of others — which they used as an opportunity to image his phone.

The FBI obtained court authority to conduct a delayed-notice search warrant pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 3103a(b), which allowed the FBI to image Wolfe’s smartphone in October 2017. This was conducted while Wolfe was in a meeting with the FBI in his role as SSCI Director of Security, ostensibly to discuss the FBI’s leak investigation of the classified FISA material that had been shared with the SSCI. That search uncovered additional evidence of Wolfe’s communications with REPORTER #2, but it did not yet reveal his encrypted communications with other reporters.

Imaging the phone was not sufficient to discover his Signal texts.

Last December and this January, the FBI had two more interviews with Wolfe where they explicitly asked him questions about the investigation. At the first one, even after he admitted his relationship with Watkins, Wolfe lied about the conversations he continued to have on Signal.

The government was able to recover and view a limited number of these encrypted conversations only by executing a Rule 41 search warrant on the defendant’s personal smartphone after his January 11, 2018 interview with the FBI. It is noteworthy that Signal advertises on its website that its private messaging application allows users to send messages that “are always end-to-end encrypted and painstakingly engineered to keep your communication safe. We [Signal] can’t read your messages or see your calls, and no one else can either.” See Signal Website, located at https://signal.org. The government did not recover or otherwise obtain from any reporters’ communications devices or related records the content of any of these communications.

Then, in a follow-up meeting, he continued to lie, after which they seized his phone and found “fragments” of his Signal conversations.

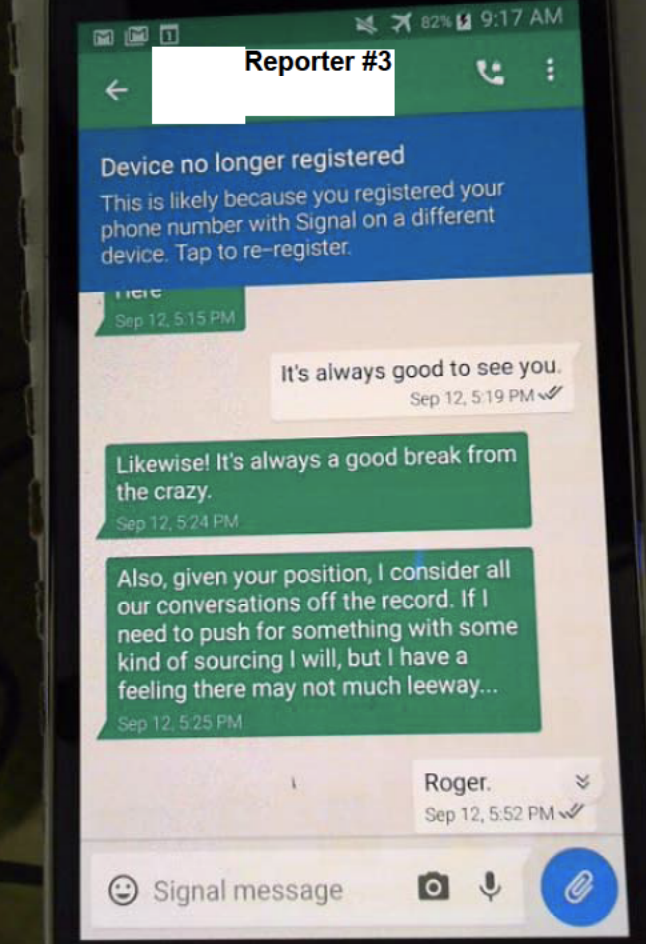

It is noteworthy that Wolfe continued to lie to the FBI about his contacts with reporters, even after he was stripped of his security clearances and removed from his SSCI job – when he no longer had the motive he claimed for having lied about those contacts on December 15. During a follow-up voluntary interview at his home on January 11, 2018, Wolfe signed a written statement falsely answering “no” to the question whether he provided REPORTER #2 “or any unauthorized person, in whole or in part, by way of summary, or verbal [or] non-verbal confirmation, the contents of any information controlled or possessed by SSCI.” On that same day, the FBI executed a second search warrant pursuant to which it physically seized Wolfe’s personal telephone. It was during this search, and after Wolfe had spoken with the FBI on three separate occasions about the investigation into the leak of classified information concerning the FISA application, that the FBI recovered fragments of his encrypted Signal communications with REPORTERS #3 and #4.

They specify that this second warrant was a Rule 41 warrant, which would mean it’s possible — though by no means definite — that they hacked the phone.

The government was able to recover and view a limited number of these encrypted conversations only by executing a Rule 41 search warrant on the defendant’s personal smartphone after his January 11, 2018 interview with the FBI. It is noteworthy that Signal advertises on its website that its private messaging application allows users to send messages that “are always end-to-end encrypted and painstakingly engineered to keep your communication safe. We [Signal] can’t read your messages or see your calls, and no one else can either.” See Signal Website, located at https://signal.org.

Mind you, this still doesn’t tell us much (surely by design). In another mention, they note Signal’s auto-delete functionality.

Given the nature of Signal communications, which can be set to delete automatically, and which are difficult to recover once deleted, it is impossible to tell the extent of Wolfe’s communications with these two reporters. The FBI recovered 626 Signal communications between Wolfe and REPORTER #3, and 106 Signal communications between Wolfe and REPORTER #4.

Yet it remains unclear (though probably likely) that the “recovered” texts were Signal (indeed, given that he was lying and the only executed the Rule 41 warrant after he had been interviewed a second time, he presumably would have deleted them then if not before). DOJ’s reply memo also reveals that Wolfe deleted a ton of his texts to Watkins, as well.

The defendant and REPORTER #2 had an extraordinary volume of contacts: in the ten months between December 1, 2016, and October 10, 2017, alone, they exchanged more than 25,750 text messages and had 556 phone calls, an average of more than 83 contacts per day. The FBI was unable to recover a significant portion of these text messages because they had been deleted by the defendant.

All of this is to say two things: first, the government would not pick up Signal texts — at least not deleted ones — from simply imaging a phone. Then, using what they specify was a Rule 41 warrant that could indicate hacking, they were able to obtain Signal. At least some of the Signal texts the government has revealed pre-date when his phone was imaged.

That’s still inconclusive as to whether Wolfe had deleted Signal texts and FBI was able to recover some of them, or whether they were unable to find Signal texts that remained on his phone when they imaged it in October.

Whichever it is, it seems clear that they required additional methods (and custody of the phone) to find the Signal texts revealing four relationships with journalists he had successfully hidden until that point.

Which is why I worry that the government will claim it was unable to solve the investigation into who leaked Carter Page’s FISA order because of Signal, and use that claim as an excuse to crack down on the app.

Australia has a new law requiring encrypted apps to give the government access to comms once a court order is made.

“requiring encrypted apps to give the government access”

This will go like money hiding. 5-eyes members can pass a law requiring bank deposits to be disclosed under court order, but I heavily suspect that the Swiss banks will remain secret.

The apps like Signal will move headquarters to appropriate countries where 5-eyes laws remain simply foreign laws, don’t apply here, move along swiftly please.

Remember the Elcomsoft case, when Adobe fluffed its tail…

Next target therefore: VPNs.

Just curious if there is any history of the feds dancing around in court filings with under representing what they can actually read? Either to push for more options to capture data, or to underplay capabilities and keep potential targets off guard?

I don’t know enough about the definition of terms like “recover” to know if there is wiggle room, for example. Is it being used to refer to 100% reconstitution of a message and all relevant data associated with it, so that capturing the text and 90% of the data isn’t reported as recovering a message?

You’ll see the term “parallel construction” around here a lot. That’s the process by which the government takes a super secret collection ability to get information, then finds a way to get it using some less interesting way that defense attorneys won’t find alarming and new.

I’m sure some of that happened in this case.

@BobCon: The trying to get a court to force Apple to unlock a phone, then backing out at the last minute and “discovering” that they had some capability in house. Gov want a judgement that forcing is lawful, but they won’t risk a judgement that it isn’t.

Hmmm…..

Wonder what this conviction does to the argument posited by some the “Lying to the FBI isn’t a crime!”

Of course acknowledging the fallacy of one’s position doesn’t come naturally to that crowd.

This article exposes the insufficiencies of the government (any government) has to control those who have the means and desire to hide their crimes. Violations of patent laws, intelligence leaks, back door channels are all done offshore, encrypted, or maybe even transmitted via little know transmission frequencies. If the Feds want to keep data secure, it is well past time it decides that a real problem exists that cannot be controlled using just technology. Laws and enforcement need to augment this control. The world of data breaches is not just akin to what launderers do with dirty money, it is ubiquitous in every aspect of our lives, including law enforcement. This is why Russia has been so successful. They have figured out how to use these vulnerabilities. The thing is that even though they have opened the Pandora’s Box, they also do not know how to control it.

Ironically, the only people who will be unaffected by the world of data are the people in the poorest nations who live the simplest of lifestyles.

As always, great reporting and analysis!

When you say the government might use this inability to “solve” the Page investigation as pretext to crack down on encrypted messaging apps, what does that crackdown look like? Would they be seeking to force these companies to create/surrender backdoor access to the encryption? Or would they seek a more punitive remedy?

Reply to Pat Neomi

I am not an engineer but….. no, wait… I AM an engineer.

It’s access that governments want, not a representative geek or two sitting in jail. So the long term solution would be outlawing offending phones and software. The short term? It could get nasty.

(After posting here for many months, today I got the Brass Ring: “Reply button doesn’t work.” Now I *really* feel like an Emptywheel-er.) :-)

Perhaps the “Reply button doesn’t work” is actually an encrypted message. Translation: “We received your reply attempt and regret to inform you that it is considered irrelevant to the topic.