In Thursday Hearing, Mueller’s Team Gets Specific about What They Can Do without Whitaker’s Pre-Approval

Yesterday, the DC Circuit held a hearing on Roger Stone aide Andrew Miller’s challenge of a grand jury subpoena. To make it crystal clear that the issues may have changed when Trump forced Jeff Sessions’ resignation the day before, the very first thing Judge Karen Henderson did was to instruct the sides to “Argue this case as if it were being argued yesterday morning.” She said then that they’d probably ask the lawyers to brief how Matt Whitaker’s appointment changed things, and today the panel ordered 10 page briefs, “addressing what, if any, effect the November 7, 2018 designation of an acting Attorney General different from the official who appointed Special Counsel Mueller has on this case.” Those briefs aren’t due until November 19, suggesting there won’t be an immediate resolution to Miller’s testimony.

But it was just as interesting how the Whitaker hiring may have influenced what the parties said yesterday.

Whitaker’s nomination undermines the Miller/Concord challenge to Mueller

Whitaker’s nomination really undermines the arguments that Miller and Concord Management (who argued as an amici) were making about Mueller’s appointment, particularly their argument that he is a principal officer and therefore must be Senate confirmed, an argument that relies on one that Steven Calabresi made this spring. Indeed, Neal Katyal and George Conway began their argument that Whitaker’s appointment is illegal by hoisting Calabresi on his petard.

What now seems an eternity ago, the conservative law professor Steven Calabresi published an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal in May arguing that Robert Mueller’s appointment as special counsel was unconstitutional. His article got a lot of attention, and it wasn’t long before President Trump picked up the argument, tweeting that “the Appointment of the Special Counsel is totally UNCONSTITUTIONAL!”

Professor Calabresi’s article was based on the Appointments Clause of the Constitution, Article II, Section 2, Clause 2. Under that provision, so-called principal officers of the United States must be nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate under its “Advice and Consent” powers.

He argued that Mr. Mueller was a principal officer because he is exercising significant law enforcement authority and that since he has not been confirmed by the Senate, his appointment was unconstitutional. As one of us argued at the time, he was wrong. What makes an officer a principal officer is that he or she reports only to the president.

While it may be true (as Conway argued at the link) that Calabresi’s arguments are wrong for Mueller, if they’re right for Mueller, then they’re all the more true for Whitaker. So if Mueller should have been Senate confirmed, then Whitaker more obviously would need to be.

Dreeben lays out the scope of what Mueller can do with Whitaker in charge

I’m more fascinated by subtle ways that the nomination may be reflected in Michael Dreeben’s comments, though.

In their response to Miller’s challenge, Mueller’s team laid out that they had close supervision from Rod Rosenstein, but they didn’t get into specifics. It describes how the Attorney General receives information (in the form of urgent memos), and the AG can demand an explanation and intervene if he finds an action to be “so inappropriate or unwarranted under established Departmental practices that it should not be pursued.”

The Special Counsel readily meets this test. The Attorney General receives a regular flow of information about the Special Counsel’s actions; he can demand an explanation for any of them; and he has power to intervene when he deems it appropriate to prevent a deviation from established Departmental practices. The regulation envisions deference by requiring the Attorney General to stay his hand unless he determines that an action is “so inappropriate or unwarranted under established Departmental practices that it should not be pursued.” 28 C.F.R. § 600.7(b) (emphasis added). But while the Attorney General must “give great weight to the views of the Special Counsel,” id., the provision affords the Attorney General discretion to assert control if he finds the applicable standard satisfied. This authority—coupled with the Attorney General’s latitude to terminate the Special Counsel for “good cause, including violation of Departmental policies,” 28 C.F.R. § 600.7(d)—provides substantial means to direct and supervise the Special Counsel’s decisions.

And the brief describes how Mueller has to ask for resources (though describes that as happening on a yearly basis) and uphold DOJ rules and ethical duties.

The Special Counsel is subject to equally “pervasive” administrative supervision and oversight. The Attorney General controls whether to appoint a Special Counsel and the scope of his jurisdiction. 28 C.F.R. § 600.4(a)-(b). Once appointed, the Special Counsel must comply with Justice Department rules, regulations, and policies. Id. § 600.7(a). He must “request” that the Attorney General provide Department of Justice employees to assist him or allow him to hire personnel from outside the Department. Id. § 600.5. The Special Counsel and his staff are “subject to disciplinary action for misconduct and breach of ethical duties under the same standards and to the same extent as are other employees of the Department of Justice.” Id. § 600.7(c). And, each year, the Attorney General “establish[es] the budget” for the Special Counsel and “determine[s] whether the investigation should continue.” Id. § 600.8(a)(1)-(2). The Attorney General’s initial control over the existence and scope of the Special Counsel’s investigation; his ongoing control over personnel and budgetary matters; his power to impose discipline for misconduct or a breach of ethical duties; and his authority to end the investigation afford the Attorney General substantial supervision and oversight, which supplements the Attorney General’s regulatory power to countermand the Special Counsel’s investigative and prosecutorial decisions. [my emphasis]

Significantly (given the Calebresi argument) the Mueller team briefed that US Attorneys are also inferior officers, though they get to act without pre-approval.

Miller asserts that the Special Counsel has the authority to make final decisions on behalf of the United States because the regulation “nowhere require[s] the Special Counsel to seek approval or get permission from the [Attorney General] before making final decisions about who to investigate, indict, and prosecute.” Br. 22. That was also true of United States commissioners—who could issue warrants for the arrest and detention of defendants—but who nonetheless “are inferior officers.” Go-Bart Importing Co. v. United States, 282 U.S. 344, 353 (1931). And it is true for United States Attorneys, 28 U.S.C. § 547, who are also inferior officers. See Myers v. United States, 272 U.S. 52, 159 (1926); Hilario, 218 F.3d at 25-26; United States v. Gantt, 194 F.3d 987, 999 (9th Cir. 1999); United States Attorneys—Suggested Appointment Power of the Attorney General— Constitutional Law (Article II, § 2, cl. 2), 2 Op. O.L.C. 58, 59 (1978) (“U.S. Attorneys can be considered to be inferior officers”).3 Few inferior-officer positions require a supervisor to review every single decision. See, e.g., Edmond, 520 U.S. at 665; C46 n.22. Thus, the Special Counsel’s authority to act without obtaining advance approval of every decision cannot transform the Special Counsel into a principal officer, requiring presidential appointment and Senate confirmation.

[snip]

More recently, Congress has enacted legislation allowing for the appointment of U.S. Attorneys by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate, 28 U.S.C. § 541(a); by a court, id. § 546(d); or by the Attorney General, id. § 546(a)—the latter two appointment authorities manifesting Congress’s understanding that U.S. Attorneys are inferior officers. And every court that has considered the question has concluded that U.S. Attorneys are inferior officers. Thus, to the extent that the Special Counsel “can be accurately characterized as a U.S. Attorney-at-Large,” Br. 17; see 28 C.F.R. § 600.6 (Special Counsel has the “investigative and prosecutorial functions of any United States Attorney”), the Special Counsel, like any U.S. Attorney, would fall on the “inferior officer” side of the line.

This latter argument doesn’t address the Miller/Concord claim that Mueller should have been Senate approved, but that’s part of why the Whitaker appointment is so damaging to this argument.

Compare all that with what Dreeben did yesterday. He specifically listed things that prosecutors — whether they be AUSAs or US Attorneys (though a later argument could point out that AUSAs need the approval of a USA) — do all the time: seek immunity, make plea deals, and bring indictments.

Prosecutors do this all the time. They seek immunity. They make plea agreements,. They bring indictments.

Dreeben later specified specifically what they’d need to get pre-approval for: subpoenaing a member of the media or, in some cases, immunizing a witness.

We have to get approval requires just like US Attorneys do. If we want to subpoena a member of the media, or if we want to immunize a witness, we’re encouraged if we’re not sure what the policy or practice is, to consult with the relevant officials in the Department of Justice. If we wanted to appeal an adverse decision, we would have to get approval of the Solicitor General of the United States. So we’re operating within that sort of supervisory framework.

But otherwise, per Dreeben’s argument yesterday, they wouldn’t need Whitaker to pre-approve most actions, including indictments — only to respond to an urgent memo by saying such an action was outside normal DOJ behavior.

Given my suspicions that John Kelly may be the Mystery Appellant challenging a Mueller request, Dreeben’s very detailed description of US v. Nixon’s assumptions about special prosecutors is particularly notable. His comments were intended to use US v. Nixon to support the existence of prosecutors with some independence. He very specifically describes how US v. Nixon means that the President can’t decide what evidence a prosecutor obtains in an investigation.

The issue in that case was whether a dispute was justiciable when the President of the United States exerted executive privilege over particular tapes and a special prosecutor was preceding in court in the sovereign interests of the United States to obtain evidence for a pending criminal case. And the President’s position was, I’m President of the United States. I’m vested with all executive authority, I decide what evidence is to be used in a criminal case. This is just a dispute between me and someone who is carrying out on a delegated basis a portion of my authority, it is therefore not justiciable. And the Supreme Court’s reasoning was, well, it actually is, because under a legal framework, the President does not have day-to-day control over individual prosecutions. That authority is vested in the Attorney General who is the representative of the United States as sovereign, in court. And he, exercising the powers under 28 USC 515, 533, and a couple of other statutes that dealt with powers being vested in the Attorney General and powers being delegated down, but acting pursuant to those powers, appointed a special prosecutor and vested him with a unique set of powers and those powers enabled him to go into court and to meet head to head in an adversarial proceeding the President’s claim as President that particular tapes were covered by Executive Privilege as against the sovereign’s claim through the special prosecutor that these tapes were relevant and admissible in a pending criminal case. [my emphasis]

None of this is a revolutionary interpretation of US v. Nixon. But the mystery dispute pertains to Kelly’s testimony — or some other move on the part of the White House to dictate what Mueller can and cannot do — then the language is notable, particularly given that two of the judges in yesterday’s hearing, Judith Rogers and Sri Srinivasan, have been the judges working on the mystery appeal.

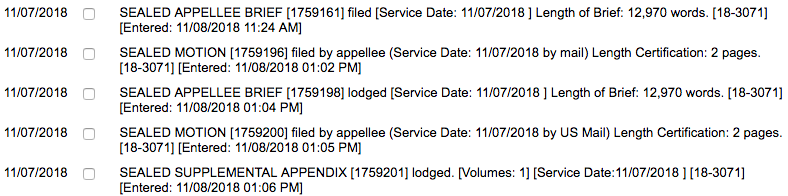

Notably, along with submitting their brief in that appeal yesterday, Mueller’s team submitted a sealed appendix.

This sealed supplemental appendix may pertain to something Mueller just got, which would suggest that appeal may have everything to do with why Sessions was fired right away.

We’ll learn more when Mueller submits his brief on November 19 (though by then this will likely be ancient history).

But it sure seems like Dreeben was making the first argument about limits to how much Whitaker can tamper in the Mueller investigation.