Democracy Against Capitalism: Competing Stories About Wages

Ellen Meiksins Wood’s book Democracy against Capitalism, tells a story of capitalism at odds with the story economists tell. At the root of this is her view that we make a big mistake when we separate politics from economics. Here’s an example, summarized from three prior posts, one at Emptywheel, and this one and this one at Naked Capitalism. The original posts give more detailed discussions.

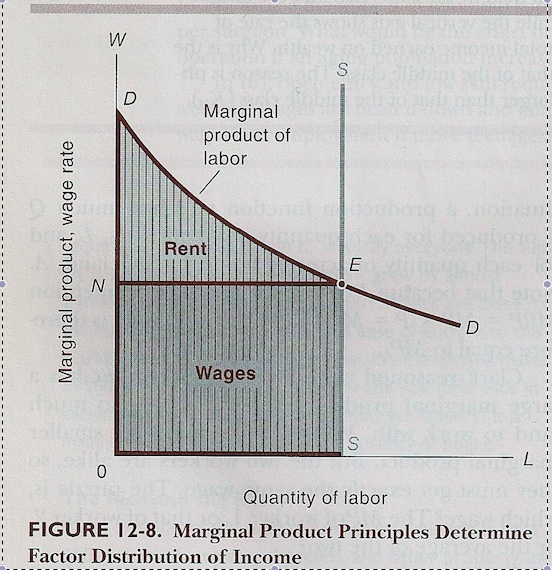

Chapter 12 of Samuelson and Nordhaus’ intro textbook Economics (2005 ed.) is titled How Markets Determine Incomes. They rely on marginal utility theory, invented by William Stanley Jevons, an English mathematician and economist and described in his 1871 book The Theory of Political Economy discussed here. Their explanation uses this chart. P. 238.

The y-axis is the marginal product of labor, with all other inputs held constant. The x-axis is the amount of labor, here the number of employees. We treat the labor as continuous so we can have a nice smooth curve, but in the real world it would look like a flight of stairs. The authors tell us that the employer will add workers until the marginal increase in revenue from the last worker is zero. They tell us that the bottom rectangle is wages, and the top triangle-ish shape DEN is rent. That’s because they are basing their explanation on John Bates Clark’s model from about 1900, and the idea is that this chart describes a farm. But they mean that this works for the economy as a whole, so it includes all workers on one hand, and all capitalists, that is, those who own the factories, smelters, coal mines, etc. on the other. This is their discussion:

Clark reasoned as follows: A first worker has a large marginal product because there is so much land to work with. Worker 2 has a slightly smaller marginal product. But the two workers are alike, so they must get exactly the same wage. The puzzle is, which wage? The MP (marginal production) of worker 1, or that of worker 2, or the average of the two?

Under perfect competition, the answer is clear: Landlords will not hire a worker if the market wage exceeds that worker’s marginal product. So competition will ensure that all the workers receive a wage rate equal to the marginal product of the last worker.

But now there is a surplus of total output over the wage bill because earlier workers have higher MPs than the last worker. What happens to the excess MPs…? The rest stays with the landlords as their residual earnings, which we will later call rent. Why…? The reason is that each landlord is a participant in the competitive market for land and rents the land for its best price. 237-8, emphasis in original.

Clark saw this as the result of the Natural Law, and pronounced it just. This is the model taught to generations in introductory economics. The logic seems questionable, but it doesn’t matter because it isn’t how things actually happen, as I demonstrate in the linked posts.

How would a Marxist like Wood describe this model? She divides society into two groups, the producers, in this case, the farmers, and the appropriators, in this case the landlords (ignoring detail), or the workers and the capitalists. At an earlier part of the history of this society, the land was handed to the landlords, or they took it violently when government was fragmented and power represented government. Wood is talking about England, but something similar happened in the US. As a result, the producers, here the farmers, were separated from the means of production, meaning the land and perhaps some of the tools and animals needed to grow crops, and the landowners were able to expropriate the surplus created by the producers. This is a rough description of what Marx called primitive accumulation (again ignoring details and not precisely following Wood).

Primitive accumulation didn’t happen by accident. It was done by some form of coercion by some sort of ruling class. Gradually the ruling class consolidated into states, and the process continued through the arms of the state. As an example, consider Polanyi’s description in The Great Transformation of the process of “enclosure” as it was called in England.

Turning to the chart, we ignore the marginal productivity stuff and treat the line NE as the level appropriators currently pay the producers. It is as low as the appropriators can make it, using both their control of the state, and their control of the process of production. If you have any doubts about that, read the discussion of the Phillips Curve and especially a paper by Simcha Barkai here. The capitalists appropriate the triangle DEN, which represents the surplus labor, for themselves.

As always, the disposition of surplus labour remains the central issue of class conflict; but now, that issue is no longer distinguishable from the organization of production. The struggle over appropriation appears not as a political struggle but as a battle over the terms and conditions of work. Kindle Loc. 804-806

The organization of production is controlled by the appropriators with the coercive assistance of the State as needed. If the producers were smart, they would struggle with the appropriators over that surplus. They’d elect governments that would take their side in the struggle over the allocation, they’d resist and force change. There is nothing but political power that requires payment of all of the surplus labor to capital.

So now we have two stories. To me, the Samuelson/Nordhaus/Clark story is dumb. It takes the economy as a given, as if things had always been this way. In other versions of their story, we get a few shards of carefully selected history that pretend to find seeds of capitalism in earlier times. Mostly, though, it’s a vision of capitalism as an inevitable and fixed system as available for study as a cadaver.

In addition, this story makes the outcomes seem pre-ordained, and leads people to think that interference with the process is both useless and somehow dangerous, certain to produce even worse results. And, it’s a just-so story: all the numbers appear to come out in perfect equilibrium as if by magic.

Wood’s story is easy to understand. It’s based in history, none of that man-made natural law mumbo-jumbo. It doesn’t call for absurd assumptions to make everything work out beautifully. It’s easy to see how this story can motivate action, and, of course, reaction. And here’s the key point: it’s easy enough to tell the this story without direct reference to Marx.

Having worked in a factory for many years, I can faithfully report that industrial managers always seeks to increase “operational control” over workers, often at the expense of profit, and on the presumption that greater control will eventually lead to increased profit. That assumption is often wrong but never abandoned. So I call it the control motive. And I call the profit motive a fig leaf covering the embarrassment of what frequently amounts to managerial sabotage of industrial operations.

I have no idea how to apply those terms to an entire economy writ large. Perhaps the fewer the agents of control, the less efficient the overall operation becomes. But that’s just a guess based upon anecdotal experience. Is it possible for managerial sabotage to characterize an entire economic system?

Adam Smith knew that this was the case. I don’t think he offered a solution.

“The pride of man makes him love to domineer, and nothing mortifies him so much as to be obliged to condescend to persuade his inferiors. Wherever the law allows it, and the nature of the work can afford it, therefore, he will generally prefer the service of slaves to that of freemen.”

Having worked in a factory for many years, I can faithfully report that industrial managers always seeks to increase “operational control” over workers, often at the expense of profit, and on the presumption that greater control will eventually lead to increased profit. That assumption is often wrong but never abandoned. So I call it the control motive. And I call the profit motive a fig leaf covering the embarrassment of what frequently amounts to managerial sabotage of industrial operations.

I have no idea how to apply those terms to an entire economy writ large. Perhaps the fewer the agents of control, the less efficient the overall operation becomes. But that’s just a guess based upon anecdotal experience. Is it possible for managerial sabotage to characterize an entire economic system?

Here’s the key:

The beauty of this formulation is that it (and the law) deprives workers of agency and directs them to fight a narrow battle for little gain against a single employer at the periphery of the field. It is well away from the center of politics and the power that drives its choices. These are hidden away in an attic wardrobe, along with the disused fur coats and the doorway to Narnia.

Replacing them for public viewing is the almighty economy, ordained by if not replacing the Almighty, whose neoliberal workings are as natural and unchangeable as that kings rule and bees have wings.

It is against all the law and the prophets, heretical and unnatural to argue or fight for any other distribution of resources. The only possible gap filler between rich and poor is charity. That this is inadequate and can be withdrawn on a whim is a feature. It keeps the queue peaceful and in line. No jumping allowed. It would be unfair. The psychological manipulation is breathtaking in its simplicity and power.

Thanks, Ed.

One expression of the law working hard for capital is the Taft-Hartley Act (the neutrally named but vehemently pro-capitalist Labor Management Relations Act of 1947), passed under Truman.

Taft-Hartley came in response to the unusual labor victory embodied in 1935’s National Labor Relations Act (the Wagner Act).

The Depression Era Wagner Act, signed by FDR, pushed through the Senate by NY’s Bob Wagner, and backed by his pioneering Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins, had attempted to level the playing field by undoing the legal restraints that had been placed on organized labor for much of the American experience. Taft-Hartley reimposed them with a vengeance.

European commentators at the time observed that in no other western democracy was a supposedly neutral government so decidedly one-sided in favoring management over labor in their perennial conflict.

That was the beginning of the so-called Right-to-Work Laws adopted in The South and Southwest. When The Department of Defense began shifting defense contracts to Right-To-Work states, the diaspora from The South to The North slowed down and was eventually reversed. (There were other factors in the internal migration from The North to The South)

But the death knell was first sounded between 1963 and 197o during the reverse decimation of The International Longshoreman’s Union following the containerization of ports, the intermodal transportation system, the bar-code scanner techonology to keep track of it all and the eventual rise of big box retailers such as Walmart, Home Depot, Best Buy et al.

Those developments were all funded by our tax dollars for the sake of projecting US military power in two hemispheres at the same time. As far as I’m concerned, The Walton Family owes US their inheritance tax assessments and then some.

The wealth elite hated much of FDR’s legacy, the NLRA and Social Security most of all. They are still trying to undo the vestiges of his progressive programs. But it was unseemly to promote so vehement an anti-labor law outright. Cover was needed to persuade people that the wealth elite and its GOP were acting in a public rather than private parochial interest.

Taft-Hartley was passed under the rubric of fighting the communist hordes. They sneak in under cover of promoting social justice, you see, eating away at democratic societies like wasp larvae in the belly of a worm. The propaganda was as brutal as the Act’s provisions.

Not to worry, the contemporary CIA was acting more directly in opposing labor in Europe, preferring the Italian mafia to leftist labor unions in places like Marseille, one outcome of which was to give us the venerable French Connection.

Not surprisingly, the Right’s intentional association of communism – America’s favorite subject for its two minutes of hate – with progressive politics damns them both. Felllow travelers and dupes all, you see, even if they don’t realize that promoting social justice is really a prayer for Stalinesque terror.

earlofguntington gives a great example. It’s important to note that a majority of House democrats and half of Senate democrats support this pig bill, I don’t know whether they were doing the bidding of their donors, or whether they were spooked by all the communism grabage, but it’s just another example of how the democrats betray the working class.

It wasn’t necessary for the dems to act like cowards in response to the communist crap that came to dominate politics until until Trump fel in with Russia. The labor unions were busy purging their communists, of which there were more than a few, as well as their socialists and their real activists, leaving unions bereft of activist leadership and compliant with the demands of the CEO class. This opened the door for further union=busting, and for the idiot idea that unions are icky that seems to doinate the views of the working class today: as an example, see the failure to organize VW plants in Tennessee a couple of years ago, despite the nominal support of management.

As to whether capitalism and democracy are compatible, I would say that they are generally incompatible, because of capitalism’s tendency toward extreme inequality of wealth and income.

Democracy entails voting, and if the people voting are not social, political, and (at least approximately) economic equals, then the essential feature of ‘one person, one vote’ is not achievable.

“Workers of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains”, Marx and the Wobblies. There was a brief, often bloody, period when organized labor managed to wrest a portion of the fruits of their labor from capital. It was amazing what that pressure plus defusing the appeal of the Commies and worldwide economic collapse did to encourage capitalists share a little more with workers. But, I suppose that gets ahead of your story line.