Confirmed: The FISA Court Is Less of a Rubber Stamp than Article III Courts

Although Rosemary Collyer’s recent 702 opinion has made me rethink my position, I’ve long argued that the FISA Court gets a bad rap when it is called a rubber stamp.

But today, for the first time, we can test that claim. Today is the first time we have had US Court reports for for an entire year for both the FISC and for Article III Courts — as close as we can get to comparing apples to apples.

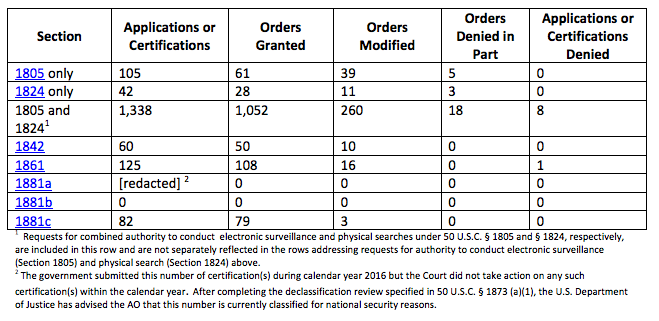

The FISC report showed that that court denied in full 8 of 1485 individual US based applications, at a rate of .5%, along with partially denying or modifying a significant number of others.

The Article III report showed that out of 3170 requests, state and federal courts denied just 2 requests.

A total of 3,168 wiretaps were reported as authorized in 2016, compared with 4,148 the previous year. Of those, 1,551 were authorized by federal judges, compared with 1,403 in 2015. A total of 1,617 wiretaps were authorized by state judges, compared with 2,745 in 2015. Two wiretap applications were reported as denied in 2016.

That’s a denial rate of .06%.

And remember, just 336 or so of the FISA orders target Americans, whereas the majority of the Article III warrants would target Americans.

None of that diminishes the potential privacy implications of either kind of warrant. Indeed, the relative ease with which Article III courts grant warrants may invite — as the differential standards for location data already have — FBI to use criminal courts when a FISC order would be too hard to obtain.

But if people are worried about rubber stamp courts, they probably need to focus more closely on the magistrate courts in their backyard.

Update: Swapped Article for Title because I was being an idiot. Thanks to JT for nagging.

Update: We get complaints from one of everyone’s favorite magistrates, Stephen Smith.

Please remind your devoted readers that federal magistrate judges do not issue wiretaps. That fun task is reserved for the federal article III judges with lifetime appointments. We do issue all the other electronic surveillance orders and warrants, but unfortunately no stats are kept by anyone on our grants/denials/modifications. DOJ does keep track of pen/traps obtained, but of course the judge’s role on those is purely clerical–we don’t review the evidence, but merely check to see that the application is signed by the AUSA and in proper form. Some of us are working on the MJ warrant reporting issue, which is a pet peeve of mine. But I do not think it fair to tar all federal magistrate judges with the rubber stamp label, especially not based on the wiretap numbers with which we have nothing to do.

Corrected accordingly, and my apologies to the magistrates I’ve maligned.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia-80x80.jpg)

I think your last point is not being emphasized enough, …, that way too many warrants are being approved. At all levels.

Is there any followup data on how many warrants lead to changes being placed?

The foundation for this is too shaky. To start with, as I recall, judges are mostly coming from being prosecutors much more so than from being defense attorneys. This brings in an inherent bias in the overall system, unbalanced by opposing experiences. While one can claim prosecutors have more experience representing victims, defense attorneys also know something about the weight that the state can bring down on a person. Add to that, that at the FISC level there is a further danger in that without any kind of adversarial balance opposing the warrants, sooner or later the shear mass of a constant barrage of ‘these are bad guys, we have to investigate them’ will wear down the natural skepticism that the judges should have regarding claims made in one direction or another; when they rotate back to the other courts, that has to affect them there as well, further poisoning the system.

Having known judges, both early at FISC and later, by what I know, I would say that you ought step back from this. It is cheap and easy for us here to carp, but you have no idea what they are looking at.

Do they get it wrong more than you would hope? Sure. Is it anywhere near what critics may think or allege? Nope.

Do most people have any clue as to the relative distinctions between real Article III courts, standard Title III applications and FISC matters? Naw, not even close. And I can easily say that, watching the comments here, which is a fairly informed commentariat compared to almost anywhere on the net.

Marcy has laid this out better than anyone in the standard media has. And she is right. I would advise all to read again, consider what she has propounded, and take a chill pill. This area of law is really complex.

Many thanks.

Long hot day at the office?

Your slightly emotional response illustrates the point I made in my comment — that judges are subjected to ‘… barrage of ‘these are bad guys, we have to investigate them’ ‘.

Nothing in what I wrote contradicts in any way what Marcy wrote:

Keep that in mind and my comment is on point. Directly on point. I asked, based on Marcy’s presentation, “Is there any followup data on how many warrants lead to changes being placed?”. This is a testable question. In fact, I was brief, follow it to its fullness: are the warrants leading to charges?, leading to trials?, leading to convictions? are there judgements being overturned?

No these are not comfortable questions, but they need to be asked. And as a side note, perhaps you are letting the tone of some of the questions in my initial comment steer your response. PTSD is real, it does not impugn the character of the person that has it.

No, my “day at the office” was just fine, thanks. (It is pretty hot here though!) And, no, your question is not all that “testable”. But because you don’t do this, you don’t know that, in spite of thinking you do. Which is cool, it is a very good thing you are interested.

But warrants/orders are not at all linear with formal “investigations”. Investigations have “targets” and, lesser, “subjects”. Warrants/orders may be issued against either class, or….others related. You don’t know in any given case. And there is not necessarily a good way to track that cleanly as you suggest. It might be interesting if it could be (I’d love to see what such would show), but it really cannot. This is without even getting into how some such action occurs within the grand jury framework and never sees the light of day outside of it (without even getting into blanket orders).

So, I was not trying to be prickly, but this is just pretty convoluted stuff.

Cheers.

So, it’s only over 99 percent of the time, that both FISC and Title III courts rubber stamp.

But, I think you are to something here Marcy.

The stats don’t lie, FISC is getting ripped off by their ink pad provider.

reply to bmaz

June 28, 2017 at 7:50 pm

The reply button is at its limit…

“But because you don’t do this, you don’t know that, in spite of thinking you do.”

You are making assumptions here. This may or may not be fact.

It is testable, the data is just not yet in a readily collated form easily searchable. There are paper trails that can be matched, and with all of the work being done to turn paper archives into electronic databases, it might be very close already.

Naw, for the reasons I stated previously, among others, it is not in a “readily collated form easily searchable” nor will it anytime be so soon. And it will never be so where the public can readily access or evaluate it. And, frankly, rightfully so. And, for the record, I am talking federal, which was the original discussion between FISA and Title III in Marcy’s post, but the same mostly holds for state and county investigations too, especially given the GJ implications.

reply to bmaz

June 28, 2017 at 10:01 pm

You have been part of a site that has published entry after entry about contact chaining and mining metadata. The connections between those types of information is way more tenuous that what is involved in this setting. This setting is (essentially a small) finite universe that is actually linearly ordered — it follows a timeline. Pulling the needed information out of the separate pieces and collating them is the job of the investigator. The information is there.

http://www.uscourts.gov/forms/criminal-forms

https://www.pacer.gov

As you know, states have a similar set up. Someone has already started the process, though probably for another reason, otherwise, Marcy would have had to work a lot harder to get the numbers she did in researching this entry.

‘Green Grass and High Tides’, Counselor :)

This site has nothing to do with my real life job and experience therein. And that tells me we are not close to what you suggest, at least not with any meaningful accuracy whatsoever. That said, I honestly wish/hope you are right, because it would be very useful information. And, cheers to you too, I love the Outlaws reference!

I’m sure you have observed crooked PDFs.

There is no easy way to do a ‘big data’ when you have to deal with crooked PDFs.

See the problem?

What the hell is a “crooked pdf”??

Forgot to mention recap.

https://free.law/recap/

While very useful, does not solve crooked PDF problem.

Again, you have more than Themite level gibberish?

I rest my case.

The ‘crooked PDF’ problem.

You *could* google ‘crooked PDF’ and figure it out, but I will explain now that I have time, why the ‘crooked PDF’ problem, is, well, a problem.

And it is not easily solvable. It is similar to` humans solving a CAPTCHA, but way more effort is required.

To understand why the ‘crooked PDF’ is such a pain, you must understand that a PDF file is really a picture. Similar to a GIF or JPEG image.

See the problem? It is very hard to have a searchable database of government docs.

And you know that you can hang a picture on a wall, but you can hang it crooked.

Now, imagine that picture on the wall is a image of the Declaration Of Independence.

Now, even if the picture on the wall of the Declaration Of Independence is hanging crooked, you, as an allegedly functioning Homo Sapiens, can walk up close to the wall, and, magic, you can actually read it.

Even though it is is hanging in a crooked manner.

A computer (or computers), will have a much more difficult effort. What you find easy is not essy for the computer.

Now, a PDF that contains text, and is ‘just’ a picture of a document that was printed from a computer, well, this is a more solvable problem. Maybe.

The tool for the computer is called OCR. OCR is Optical Character Recognition.

OCR is an attempt to discern characters (and therefore words), from an image. Something, that is relatively easy for you as a human, may not be very easy for a computer.

Now, the Declaration Of Independence was handwritten. Pretty damn well in my opinion.

(including the content btw!), but point being, it was actually written in a level manner.

Having the characters being level, and as consistent as possible, nakes OCR work better.

Now, remember, a PDF is really a picture.

In order to pull the characters (and the words) out of the picture, you need OCR.

When the picture is crooked, you as a human can still read it. An OCR program will have problems.

Here is where the ‘crooked PDF’ problem comes in.

Court documents these days are normally created these days via computer. All well and fine. They may be printed too. If that printout was to be used as input to an OCR program, it will probably be able to discern the text (and the words), and put the text into a (imagine this!), a text file!

Once you have the actual text, you can start doing searches on the actual words!

You can even build a database, of, for example, related casework!

You could even search that database using keywords like, for example, ‘702’.

But the problem of ‘crooked PDFs’ will get in your way, and horribly slow you down.

So, for example, let’s say you file a FOIA request, or have to get a copy of a court document from the clerk.

What happens, way, way too often is the following:

They find the document (if already on paper), or they print the document.

Then, they take the document, that an OCR program could probably handle pretty well,

and they ‘scan to PDF’ on their multifunction printer-scanner-copier. So, the newly created PDF ends up on a pc, which they can reprint again, or, heaven forbid, send via email.

Here is where the evil comes in.

When doing the scan-to-pdf function,

the person doing this purposely puts each page on the scnner in a ‘crooked’ manner!

And of course, each crooked page is at a different angle.

Net result, OCR likely fails.

If you want to create the text in a real text file, you have to read each page (different pictures on wall, all hanging in different crooked manners) and manually type the text in.

It’s possible I’m alone among those who post even occasionally here who’s actually applied for a search warrant or wiretap (See ‘wiretapp”.) order (tho I expect at least some here have applied for the rough equivalents in civil cases).

I can’t say how may such warrants & orders I applied for.

It’s not just that I can’t remember; I always made notes. But some weren’t reported into law enforcement databases by me personally, and I can’t be sure every one was reported by anyone. The number I CAN ‘report’ is 139 – as in, at least that many.

139 isn’t a high number for a long-career prosecuting attorney; but I was only that under a decade. It could well be high (my impression is it is pretty high.) for someone who served as few years as I did. But if so my guess is that’s due to peculiarities in how some offices I was in were organized, plus I caught the immediate office’s stats reporting duty on warrants during two transition periods.

I never perceived any general correlation between the number of search warrants granted and the numbers of criminal prosecutions that came out of them; IMO there wasn’t any.

I’m sure most here will recognize right away one factor: a criminal prosecution from a given operation can result in multiple indictments against multiple people.

Other factors might not be obvious. Here are 4 (among others):

1. many L.E. ops go for long periods, years even, some thru multiple warrants, before any arrests;

2. some ops don’t result in charges at all, directly or indirectly;

3. attorneys & crime court reporters learn about ‘sealing’ directions on prospective orders & warrants, and that sometimes sealing directions are renewed, & that the process can get pretty dramatically attenuated over time; but also

4. there are ways in which not just details but even existence of warrants can get ‘hidden’, even ‘disappeared’.

The numbers that fearless leader of this blog is compelled to rely on in this post derive from obligatory reporting out of a combination of statutes, regulations & policies. Even then, next to no, indeed overwhelmingly no, substantive information even gets formally reported even internally.

Those obligations are to put numbers in boxes. That kind of reporting renders them fungible. That makes sense because the primary internal justification for complying with what little reporting that gets done is budgetary.

The warrants themselves weren’t actually 1-to-1 comparable when they were applied for, or when they were granted, or when they issued, or when they were executed on; but reducing them to numbers in boxes has an important bureaucratic effect: it makes them appear equivalent.

Other than for budget purposes, that is a highly misleading effect.

Even after decades, I can remember significant details, even some entire pages of warrant application materials. I had at least a hand in writing or editing those materials in every one of the applications I took to a judge.

In every instance, the materials told a story – and each story was in some ways unique, and often highly so, & sometimes a lot more colorfully portrayed & presented for, you know, sales purposes than later investigations were able to show.

Except for the 2 transition periods mentioned, I was never a high enough desk warrior to get put in charge of reporting stats. The most involvement I had was being asked by the person responsible for gathering & reporting.

During those transition periods, I was that person, and I asked. can’t say that I was uniformly successful in the execution of that duty, because reasons. Two of those are that during transition periods there’s a heck of a lot of moving out & in traffic, and I know I missed asking some of the departed (plus there were some actual Departed; dead prosecutors tell no stats).

Other than those two situations, I do have SOME recollection of being asked by those in charge of asking; I just don’t know if that was a uniform practice always followed. I like to think I was one of more obvious persons to ask, but after some serious time spent on the defending side of the courtroom, I learned to doubt such assumptions.

If you work in a large bureaucracy, government especially, you learn quickly what stats gathering is about: fulfilling third party obligations on at least a minimal basis & satisfying budgetary needs. The saying, Close enough for government work, is like a lot of comedy: it’s funny cuz it’s so true.

In any event, AFAIK, there is not now in existence, nor has there every been, any big fat database of search warrants and wire orders containing the kinds of details that some here seem to imagine might yield useful information to search engine.

Exactly.

As to the headline word “CONFIRMED”, I can say that the system for reporting NUMBERS at least, in relation to FISC applications, is more stringent than with almost every other type of search warrant application.

Here’s a common scenario. The rules oblige the reporting of ‘failed’ applications. But sometimes what’s experienced is that the judge says something like, It’s close – I’d like to see/need something more detail in this area or in these areas.

There was one judge who had the approach of calling in a certified court reporter and the chief investigating officer & cross-examining the officer, plus ordering a copy of the transcript of the Q & A session into the court’s file. Draw that judge & your day was shot. What was that? A refusal, a grant, both?

Less common, but it happened to me, and I doubt I’m unique: Judge says, I’m won’t sign this, but I’m not a fair standard; Judge X is available now, go see him.

Another that happened to me: creeky old judge says, This is wrong; against everything I learned in school, everything my whole life has stood for. Oookaaay, judge: could you help us in what’s offending you? Pause. It’s very personal. Further pause. Okay, I’ll sign.

How should one report those types of encounters to the person in charge of stats? Into what box does THAT person decide to dump what they’ve been told? Whenever asked, I always reported what ACTUALLY HAPPENED, leaving the box checking to my betters. It’s actually possible not even one of the applications I made was formally reported as ‘denied’, ‘failed’ or ‘refused’.

Reply to Avattoir

June 29, 2017 at 9:06 pm

Yup. what you are reporting here is consistent with issues found in the FBI’s ‘Uniform Crime Reports’ — which is NOT :) a listing of crimes committed by people wearing uniforms. Not all states require their towns’ and cities’ police departments to report statistics, some states (Illinois for example) did not participate at all for a very long time. So there is a whole lot of under reporting going on.

Yet it is a tool and it does get used. What someone has started and Marcy reported on is also a tool. it will not be complete due to whisper warrants, long term John Doe warrants etc. but it is a tool also.

jerryy, in neither of my earlier two comments did I mean to leave any impression of arguing in favor of any of reporting systems that were in place when I was actively involved in the ops aspect of such programs. All I was going for was bearing witness to general observations by bmaz on the unreality in the expectations some other commenters here expressed about what if any relevant data is amenable to computerized search.

As an ‘operations’ type, it was actually pretty rare for me to be involved to any meaningful extent at the design level of any systems for reporting or preserving data. For all the time I was in that racket & could see for myself, that role always went to folks with little to no actual recent direct experience in dealing with applications for warrants or their fruits in court settings. That may seem nuts to folks who’ve never worked in large bureaucratic settings, but I suspect no surprise to those who have.

I do remember being drafted into one initiative aimed at what for a while at least was framed as serious systemic reform (There may have been others less memorable or noticeable to a line stiff like I

was.). It arose out of a public corruption scandal, then after a few meetings was put into a holding state between neutral & park as everything headed into the next transition period. After that I was out & so don’t have direct knowledge of what happened to it. I mean, I heard that it died, but I don’t know for certain if that came about due to targeting or neglect. IAE, an impression that’s stayed with me is that (at least) most political types, whether elected or appointed (I found appointees far more annoying.), as elections approach, grow markedly discomforted by the prospect leaving behind retrievable information for whoever the winds might blow in from the next election.

About as far as I think I can go now on the subject of reform is that more authority & sharper teeth with the National Archive & Archivist respectively look the most promising approach.

Do you think this is fakenews?

With a single wiretap order, US authorities listened in on 3.3 million phone calls

http://www.zdnet.com/article/one-federal-wiretap-order-recorded-millions-phone-calls/

I did not take it that way, nothing other than as I said, ‘consistent with what is generally known about tools of this type’.

It is difficult to get and put information into useful formats and then actually make meaningful use of it. I am mindful of the expression about how it takes ten years of hard work to become an overnight success. :)

Do you know if it’s common for FBI or CIA to get feedback on FISC warrants before formally submitting them? Or do they just file an application directly for each instance?

Feedback from who? But if you are asking if apps are sometimes amended to cure defects, the answer is yes.