In Opinion Mostly Rejecting Jeffrey Sterling Appeal, Fourth Circuit Criminalizes Unclassified Tips

The Fourth Circuit just codified the principle that you can go to prison for four minutes and 11 seconds of phone calls during which you tell a reporter to go find out classified details you know about.

They just released an opinion mostly upholding Jeffrey Sterling’s conviction. The majority, penned by Albert Diaz, overturned one conviction based on whether Sterling handed a letter (about which the court seems to have misunderstood the evidence) to James Risen in Virginia, but that didn’t result in any reduction in sentence. The court not only upheld all other convictions, but did so in ways that will be really horrible for any clearance holders charged with leaks in the Fourth Circuit (the jurisdiction of which covers all the major government spy agencies).

Four minutes and 11 seconds of metadata

First, there’s the matter of whether there was evidence to support the three charges related to the first story James Risen attempted to write on Merlin in 2003. The opinion claims Sterling and Risen had “numerous” phone calls in advance of Risen going to the CIA with his story.

The government presented evidence of numerous phone calls in February and March 2003, between Sterling’s home in Virginia and Risen’s home in Maryland. These phone calls occurred right before Risen notified the CIA that he had learned about the program from confidential sources and was planning to write an article about its classified operations. Furthermore, all of these calls were made nearly a year after Risen wrote an article about Sterling’s discrimination lawsuit.

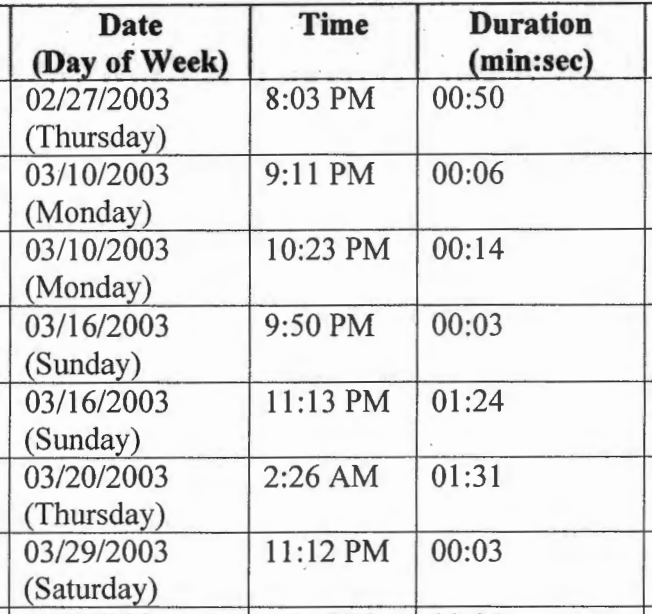

Here’s what those “numerous” calls look like:

Altogether, the government presented evidence that Sterling and Risen spoke for four minutes and 11 seconds in advance of the first story. Sterling also sent an unclassified email referring to a CNN story on Iran’s nukes.

Significantly, the court doesn’t even hold that Sterling may have transmitted classified information in those calls. It holds that he may have “encouraged” and “caused” Risen to publish the information.

That circumstantial evidence, viewed in the light most favorable to the government, could have led a rational jury to infer that Sterling discussed some classified information with Risen during these calls—the longest of which was 91 seconds—or encouraged Risen to publish the information. Thus, a jury could find that, more likely than not, Sterling helped “cause” dissemination of the information to the public through phone communications from his home in the Eastern District of Virginia, making venue proper for Counts I, II, and IX.

This establishes a standard criminalizing something that happens all the time in DC — where sources point reporters to something that’s classified without providing any classified information, leading the reporter to go find the classified information from other sources.

Importantly (and not mentioned in the Fourth Circuit opinion), the FBI’s initial suspect in this case was then-SSCI staffer Bill Duhnke. SSCI refused to cooperate with the FBI in the early stages of the investigation and may never have done so with respect to Duhnke. Nothing in the public record ever ruled out that he was Risen’s source for this early story.

The Court erroneously claims that Sterling had “the letter” printed in Risen’s book

The court makes two troubling steps in upholding Sterling’s conviction for illegally retaining classified information, which it upholds this way.

As to this offense, the Russian scientist testified that he gave Sterling a copy of the program letter in 2000. Sterling lost access to classified materials after he was fired in early 2002 (when he was working and living in Virginia), and Risen first notified authorities that he had seen the letter in April 2003. Finally, the government introduced evidence that in 2006, Sterling had stored other classified documents in his Missouri home, after he moved in mid-2003. On this evidence, a jury could therefore reasonably infer that after Sterling left the CIA in 2002, he unlawfully retained the program letter in his home—which was then in the Eastern District of Virginia.

In the language rejecting the conviction that Sterling transmitted the actual letter to Risen in Virginia, the court claimed that both sides agree that Sterling actually had the letter.

Because both sides agree that Sterling provided Risen with a paper copy of the letter, evidence of phone and email communications alone cannot support proper venue for Count V.

The claim that the defense agreed that Sterling even had the hard copy of the letter, much less handed it to Risen, is utterly inconsistent with this statement later in the opinion.

Sterling argued throughout the trial that he never retained or transmitted classified material.

Perhaps the court meant to say that “Sterling would have had to hand Risen a paper copy”?

Moreover, unless I’m missing something, not only does the defense not agree that Sterling handed over the letter, but it doesn’t even agree that Sterling ever had or saw the letter in the form handed to Risen. Indeed, the defense repeatedly got the government to admit they never found a copy of the actual letter that appeared in Risen’s book (though the record is inconsistent about whether that letter that got handed to the Iranians actually matched what appeared in Risen’s book).

That’s important — as I lay out in depth in this post — because Sterling was not involved in some key meetings leading up to the time Merlin went to Vienna. Given that he wasn’t involved in some of the meetings, it’s quite possible Sterling never saw the letter as it appeared in Risen’s book. I’d even say it’s likely, because Sterling’s habit was to include a verbatim transcript of letters Merlin was writing in his reporting, whereas Bob S, who handled the meetings Sterling didn’t attend, did not do so.

CIA has effectively — and not very credibly — claimed they didn’t have a copy of the letter as it appeared in Risen’s book, and in later years of the investigation Merlin started claiming he destroyed all evidence of it. Which would seem to undermine the claim that either side agreed Sterling handed over the actual letter to Risen.

I’m not sure how, based on that record, the Fourth Circuit can claim that Sterling ever had the letter in question.

Going to prison for keeping a procedure on how to dial a rotary phone

Then there’s what the court does to get to the claim that “in 2006, Sterling had stored other classified documents in his Missouri home, after he moved in mid-2003.”

The defense objected to the introduction of these documents, which included a performance review from the time Sterling was a trainee and instructions on how to dial into Langley from a rotary phone, specifically because of the way in which the documents were presented to the jury. The documents were handed out in red classified folders in unredacted form with great fanfare, whereas all other (far more classified) documents had been redacted and simply handed over to the jury in evidence binders.

Here’s how I described the theater surrounding these documents at the time.

A court officer handed out a packet of these same documents with bright red SECRET markings on the front to each juror (the government had tried to include such a warning on the binders of other exhibits, but the defense pointed out that nothing in them was actually classified at all). Judge Leonie Brinkema, apparently responding to the confused look on jurors’ faces, explained these were still-classified documents intended for their eyes only. “You’ll get the context,” Judge Brinkema added. “The content is not really anything you have to worry about.” The government then explained these documents were seized from Jeffrey Sterling’s house in Missouri in 2006. Then the court officer collected the documents back up again, having introduced the jurors to the exclusive world of CIA’s secrets for just a few moments.

On cross, however, the defense explained a bit about what these documents were. Edward MacMahon made it clear the date on the documents was February 1987 — a point which Lutz apparently missed. MacMahon then revealed that the documents explained how to use rotary phones when a CIA officer is out of the office. I believe the prosecution objected — so jurors can’t use MacMahon’s description in their consideration of how badly these documents implicate Sterling — but perhaps the improper description will help cue the jurors’ own understanding about what the documents they had glimpsed were really about, making it clear to them they’re being asked to convict a man because he possessed documents about using a rotary phone that the CIA retroactively decided were SECRET.

The court doesn’t deal with the silent witness aspect of this presentation at all. On the contrary, the court makes no mention of it when it dismisses the possibility this was inflammatory.

All probative evidence may be prejudicial to the defendant in some way, but we have found Rule 404(b) evidence to be unfairly prejudicial when it inflames the jury or encourages them to draw an inference against the defendant, based solely on a judgment about the defendant’s criminal character or wicked disposition. McBride, 676 F.3d at 399; Hernandez, 975 F.2d at 1041.

Here, evidence showing that Sterling had improperly retained four classified documents in the past encouraged the proper evidentiary inference that any subsequent retention of classified documents was, if proven, intentional.

The court’s treatment of these documents (and its silence on their actual content or the theater surrounding the introduction of them) is all the more troubling given that the court claimed the “prior bad acts” implicated by Sterling’s retention of these documents “were exactly the same as the act Sterling was charged with under Count III.”

Although the Rule 404(b) evidence was fairly old in this case, it did bear sufficient similarity in terms of pattern of conduct to justify its admission. An FBI search of Sterling’s Missouri home in 2006 uncovered four classified documents, which Sterling had improperly kept. And Sterling’s improper retention of these documents occurred during the same timeframe as his improper retention of files concerning the Program. Furthermore, the prior bad acts were exactly the same as the act Sterling was charged with under Count III.

Sure, in a legal sense, retaining classified information is retaining classified information. That’s how the Fourth Circuit gets to its “exactly the same” claim.

But retaining 20 year old HR documents — including a performance review — you obtained as a trainee just getting used to classification rules is not the same as retaining documents from covert operations. It’s not. And the claim it is is all the more outrageous given that Sterling wasn’t permitted to talk about how the witnesses against him had also retained classified information, and probably information that was far more classified than rotary phone dialing instructions.

Effectively, along with criminalizing sharing unclassified tips, the Fourth Circuit has also just criminalized mistakenly retaining HR documents in your basement, something that a large proportion of clearance holders have probably done over the course of their career.

Obstruction before the fact

Finally, here’s the court found that Sterling’s obstruction conviction was proper even though the government presented no proof whether he had deleted the unclassified email mentioning Iran’s nuclear program before or after receiving a subpoena for classified materials.

Sterling notes that this specific email “was not among the categories of documents requested by the grand jury’s [June 2006] subpoena.” Appellant’s Br. at 44. He argues, therefore, that even if he did delete the email, he could not have done so with the intent to impair the grand jury investigation. But while the email may not have been explicitly included in the subpoena’s categories, in that it did not directly share information about the classified program, it did reference Iran’s nuclear development efforts. Furthermore, the email and its brief comments suggest that Risen and Sterling had previously discussed Iran’s nuclear program.

We have said that to be culpable of obstructing justice, the actual documents destroyed “do not have to be under subpoena.” United States v. Gravely, 840 F.2d 1156, 1160 (4th Cir. 1988) (analyzing a conviction for obstruction of justice under 18 U.S.C. § 1503). Instead, “it is sufficient if the defendant is aware that the grand jury will likely seek the documents in its investigation.” Id. A rational jury could infer, based on the evidence at trial, that Sterling deleted the email between April and July 2006 in order to conceal it from a grand jury investigation. We therefore reject Sterling’s challenge to this conviction.

This language is just — what is the technical term? — weird.

First of all, the court never explains how Sterling would know there was a grand jury before receiving a subpoena from it, which is pretty important given that Sterling had known there was an investigation for three years, but hadn’t deleted that email before then.

Moreover, even as it deems it rational to believe that Sterling deleted the email thinking the grand jury will “likely seek the documents,” the court ignores that the grand jury actually never did seek such an email. So Sterling, with no formal notice of a grand jury introduced in the trial, not only deleted the unclassified email knowing there would be one, but happened to delete an email that the grand jury, in fact, would never go onto ask for?

Somehow, too, unless I missed it the court neglected to deal with venue on this claim. They just … ignored that part of Sterling’s appeal.

The Fourth Circuit just made it illegal to share unclassified information

So between the finding that Sterling criminally “encouraged” the transmission of classified information in four minutes and 11 seconds of phone calls of unknown content, and the finding that Sterling obstructed justice before knowing there was a grand jury by deleting information that unknown grand jury ultimately never asked for, the Fourth Circuit has just criminalized sharing unclassified information.