What Fake French News Looks Like (to a British Consulting Company)

Along with reports that APT 28 targeted Emmanuel Macron that don’t prominently reveal that Macron believes he withstood the efforts to phish his campaign, the post-mortem on the first round of the French election has also focused on the fake news that supported Marine Le Pen.

As a result, this study — the headline from which claimed 25% of links shared during the French election pointed to fake news — has gotten a lot of attention.

The study, completed by a British consulting firm (though the lead on the study is a former French journalist) and released in full only in English, is as interesting for its assumptions as anything else.

Engagement studies aren’t clear what they’re showing, but this one is aware of that

Before I explain why, let me stipulate that accept the report’s conclusion that a ton of Le Pen supporters (though it doesn’t approach it from that direction) relied on fake news and/or Russian sources. The methodology appears to suffer from the same problem some of BuzzFeed’s reporting on fake news does, in that it doesn’t measure the value of shared news, but at least it admits that methodological problem (and promises to discuss it at more length in a follow-up).

Sharing is the overt act of taking an article or video or image that one sees in social media and, literally, sharing it digitally with one’s own followers or even into the public domain. Sharing therefore implies an elevated level of interest: people share articles that they feel others should see. While there are tools that help us track and quantify how many articles are shared, they cannot explain the sharer’s intention. It seems plausible, particularly in a political context, that sharing implies endorsement, yet even this is problematic as sharing can often imply shock and disagreement. In the third instalment [sic] of this study, Bakamo will explore in depth the extent to which people agree or disagree with what they share, but for this report (and the second, updated version), the simple act of sharing—whatever the intention—is nonetheless highly relevant. It provides a way of gauging activity and engagement.

[snip]

These are the “likes” or “shares” in Facebook, or “favourites” or “retweets” in Twitter. While these can be counted, we do not know whether the person has actually clicked through to read the content being shared before they like or retweet. This information is only available to the account owner. One of the questions that is often raised about social media is whether users do indeed read the article or respond simply to the headlines that appear in their newsfeed. We are unable to comment on this.

In real word terms, engagement can be two things. It can be agreement—whether reflexive or reflective—with the content shared. It can also, however, be disagreement: Facebook’s nuanced “like” system (in which anger is a valid form of engagement) or Twitter’s citations that enable a user to comment on the link while sharing it both permit these negative expressions.

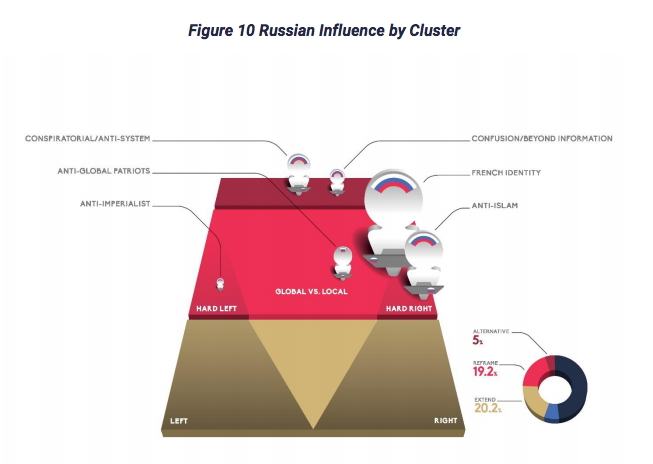

The study is perhaps most interesting for what it shows about the differing sharing habits from different parts of its media economy, with no overlap between those who share what it deems “traditional” media and those who share what I’d deem conspiracist media. That finding, more than almost any other one, suggests what might be needed to engage in a dialogue across these clusters. Ultimately, what the study shows is increased media polarization not on partisan grounds, but on response to globalization.

Russian media looks very important when you only track Russian media

As I noted, one of the headlines that has been taken away from this study is that Le Pen voters shared a lot of Russian news sources — and I don’t contest that.

But there are two interesting details about how that finding came to be that important to this study.

First, the study defines everything in contradistinction from what it calls “traditional” media.

There are broad five sections of the Media Map. They are defined by their editorial distance from traditional media narratives. The less accepting a source is of traditional media narratives, the farther away it is (spatially) on the Map.

In the section defining traditional media, the study focuses on establishment and commercialism (including advertising), even while pointing to — but not proving — that all traditional media “adher[e] to journalistic standards” (which is perhaps a fairer assumption still in France than in the US or UK, but nevertheless it is an assumption).

This section of the Media Map is populated by media sources that belong to the established commercial and conventional media landscape, such as websites of national and regional newspapers, TV and radio stations, online portals adhering to journalistic standards, and news aggregators.

It does this, but insists that this structure that privileges “traditional” media without proving that it merits that privilege is not meant to “pass moral judgement or to define what is ‘good’ or ‘evil’.”

Most interesting of all, the study includes — without detail or interrogation — international media sources “exhibiting these same characteristics” in its traditional media category.

These are principally France-based sources; however, French-speaking international media sources exhibiting these same characteristics were also placed into the Traditional Media section.

But, having defined some international news sources as “traditional,” the study then uses Russian influence as a measure of whether a media cluster was non-traditional.

The analysis only identified foreign influence connected with Russia. No other foreign source of influence was detected.

It did this — measuring Russian influence as a measure of non-traditional status — even though the study showed this was true primarily on the hard right and among conspiracists.

Syria as a measure of journalistic standards

Among the other kinds of content that this study measures, it repeatedly describes how those outlets it has clustered as non-traditional (primarily those it calls reframing outlets) deal with Syria.

It asserts that those who treat Bashar al-Assad as a “protagonist” in the Syrian civil war as being influenced by Russian sources.

A dominant theme reflected by sources where Russian influence is detected is the war in Syria, the various actors involved, and the refugee crisis. In these articles, Bachar Assad becomes the protagonist, a perspective opposite to that which is reported by traditional media. Articles touching on refugees and migrants tend to reinforce anti-Islam and anti-migrant positions.

The anti-imperialists focus on Trump’s ineffectual missile strike on Syria which — the study concludes — must derive from Russian influence.

Trump’s “téléréalité” attack on Syria is a more recent example of content in this cluster. This is not surprising, however, as Russian influence is detectable on a number of sites in this cluster.

It defines conspiracists as such because they say the US supports terrorist groups (and also because they portray Assad as trustworthy).

Syria is an important theme in this cluster. Per these sources, and contrary to reports in traditional media, the Western powers are supporting the terrorist, while Bashar Assad is trustworthy and tolerant leader, as witness reports prove.

The pro-Islam non-traditional (!!) cluster is defined not because of its distance from “traditional” news (which the study finds it generally is not) but in part because its outlets suggest the US has been supporting Assad.

American imperialism is another dominant theme in this cluster, driven by the belief that the US has been secretly supporting the Assad regime.

You can see, now, the problem here. It is a demonstrable fact that America’s covert funding did, for some time, support rebel groups that worked alongside Al Qaeda affiliates (and predictably and with the involvement of America’s Sunni allies saw supplies funneled to al Qaeda or ISIS as a result). It is also the case that both historically (when the US was rendering Maher Arar to Syria to be tortured) and as an interim measure to forestall the complete collapse of Syria under Obama, the US’ opposition to Assad has been half-hearted, which may not be support but certainly stopped short of condemnation for his atrocities.

And while we’re not supposed to talk about these things — and don’t, in part, because they are an openly acknowledged aspect of our covert operations — they are a better representation of the complex clusterfuck of American intervention in Syria than one might get — say — from the French edition of the BBC. They are, of course, similar to the American “traditional” news insistence that Obama has done “nothing” in Syria, long after Chuck Hagel confirmed our “covert” operations there. Both because the reality is too complex to discuss easily, and because there is a “tradition” of not reporting on even the most obvious covert actions if done by the US, Syria is a subject on which almost no one is providing an adequately complex picture of what is going on.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the measure of truth on Syria has become the simplified narrative you’re supposed to believe, not what the complexity of the facts show. And that’s before you get to where we are now, pretending to be allied with both Turkey and the Kurds they’re shooting at.

The shock at the breakdown of the left-right distinction

What’s most fascinating about the study, however, is the seeming distress with which it observes that “reframing” media — outlets it claims is reinterpreting the real news — doesn’t break down into a neat left-right axis.

Media sources in the Reframe section share the motivation to counter the Traditional Media narrative. The media sources see themselves as part of a struggle to “reinform” readers of the real contexts and meanings hidden from them when they are informed by Traditional Media sources. This section breaks with the traditions of journalism, expresses radical opinions, and refers to both traditional and alternative sources to craft a disruptive narrative. While there is still a left-right distinction in this section, a new narrative frame emerges where content is positioned as being for or against globalisation and not in left-right terms. Indeed, the further away media sources are from the Traditional section, the less a conventional left-right attribution is possible.

[snip]

The other narrative frame detectable through content analysis is the more recent development referred to in this study as the global versus local narrative frame. Content published in this narrative frame is positioned as being for or against globalisation and not in left-right terms. Indeed, the further away media sources are from the Traditional section, the less a conventional left-right attribution is possible. While there are media sources in the Reframe section on both on the hard right and hard left sides, they converge in the global versus local narrative frame. They take concepts from both left and right, but reframe them in a global-local context. One can find left or right leanings of media sources located in the middle of Reframe section, but this mainly relates to attitudes about Islam and migrants. Otherwise, left and right leaning media sources in the Reframe section share one common enemy: globalisation and the liberal economics that is associated with it.

Now, I think some of the study’s clustering is artificial to create this split (for example, in the way it treats environmentalism as an extend rather than reframe cluster).

But even more, I find the confusion fascinating. Particularly in the absence of — as it did for Syria coverage — any indication of what is considered the “true” or “false” news about globalization. Opposition to globalization, as such, is the marker, not a measure of whether an outlet is reporting in factual manner on the status and impact and success at delivering the goals of globalization.

And if the patterns of sharing in the study are in fact accurate, what the study actually shows is that the ideologies of globalization and nationalism have become completely incoherent to each other. And purveyors of globalization as the “traditional” view do not, here, consider the status of globalization (on either side) as a matter of truth or falseness, as a measure whether the media outlet taking a side in favor of or against globalization adheres to the truth.

I’ve written a fair amount of the failure of American ideology — and of the confusion among priests of that ideology as it no longer exacts unquestioning sway.

This study on fake news in France completed by a British consulting company in English is very much a symptom of that process.

But the Cold War is outdated!

Which brings me to the funniest part of the paper. As noted above, the paper claims that anti-imperialists are influenced by Russian sources, which it explains for criticism of Trump’s Patriot missile strike on Syria. But it’s actually talking about what it calls a rump Communist Cold War ideology.

This cluster contains the remains of the traditional Communist groupings. They publish articles on the imperialist system. They concentrate on foreign politics and ex-Third World countries. They frame their worldview through a Cold War logic: they see the West (mainly the US) versus the East, embodied by Russia. Russia is idolised, hence these sites have a visible anti-American and antiZionist stance. The antiquated nature of a Cold War frame given the geo-political transformations of the last 25 years means these sources are often forced to borrow ideas from the extreme right.

Whatever the merit in its analysis here, consider what it means for a study the assumptions of which treat Russian influence as a special kind of international influence, even while conducting no reflection on whether the globalization/nationalization polarization it finds so striking can be measured in terms of fact claims.

The new Cold War seems unaware that the old Cold War isn’t so out of fashion after all.

Social informatics is a thing. For example…if I engage via cellphone, my packet size is limited and creates less resonance as the impulse response is proportional to the finite spectral content. Twitter threads are interesting based on diversity of context over multiple tweets. More perspective broadens the bandspread of ideas which is akin to fm vs am radio. Facebook’s signal to noise ratio (per prior post) is 10log(1/.001)=30dB… Not even am radio quality. Such a metric also falls short due to the averaging over a period…the election cycle. What isn’t revealed is the peak error potential measurements in these press releases. Much resonance…aka engagement…takes place during “prime time” which is when people are most receptive. Coupling efficiency is also a factor. How much energy is transferred over the line depends on how well the medium is matched to the receiver. Sometimes content suffers from transmission errors. Filters usually fix that or ignore out-of-band signals. Like the difference between a Patriot missle vs a Tomahawk cruise missle. A small difference, but relative to context depending on whether you’re an airborne target or a ground target.

I think the inclusion of an “antiZionist stance” as an indicator of “Cold war logic” is very telling of the background of the authors.

A better frame for this kind of investigation would be looking at it from the viewpoint of an intelligence analyst.

The analyst doesn’t care who is right or wrong about a particular issue. The point is to understand viewpoints and predict behavior. A false claim by a source may indicate the inadequacy of its intelligence, its biases and blind spots, or a matter on which it wishes to deceive. All information is potentially useful.

It is relevant that Russian propaganda–not to mention financial support– has primarily gone to aid right-wing nationalist parties (except, of course, in Ukraine). It’s possible that this is just because the left in the west is so weak that it is a less-attractive target. However, this is a radical break from the past actions of the predecessor regime, which suffered unimaginable damage from right-wing states. That makes the Cold War frame a blind spot for those trying to understand the role of Russian propaganda efforts.

On the other side, we see the US reviving the Cold War frame (which may be where the articles’ biases come from). This, I suspect, is opportunistic. In shifting from Eastasia to Oceania, narratives have to be simplified. To policy makers, it doesn’t matter that the previous enemy was the USSR and the enemy-to-be is Russia, what matters is reviving memories of opposition. But the policy makers get into real trouble when they swallow their own baloney.

What we’re witnessing, I think, is a time of extreme incoherence as the world shifts toward true multipolarity. Trump is the catalyst, since he’s squandering American power and treasure, allowing Russian and Chinese soft power to grow, even as he breaks down the economic pillars of the American empire. There’s no reason to see the Russian and Chinese empires as more benign than the American, though they may temporarily offer better terms (as China has in Africa).

These are very dangerous times, and nothing is more dangerous than a powerful state sensing that it is under covert attack. Fake news by the Russians might have been a clever strategy when there was no major external threat. At a time when the US feels threatened and the world is facing ecological catastrophe, it’s too clever by half. The end result may very well be disastrous for everyone.