How to Spy on Carter Page

I have no personal knowledge of the circumstances surrounding the alleged wiretapping of Carter Page, aside from what WaPo and NYT have reported. But, in part because the release of the new, annual FISC report has created a lot of confusion, I wanted to talk about the legal authorities that might have been involved, as a way of demonstrating (my understanding, anyway, of) how FISA works.

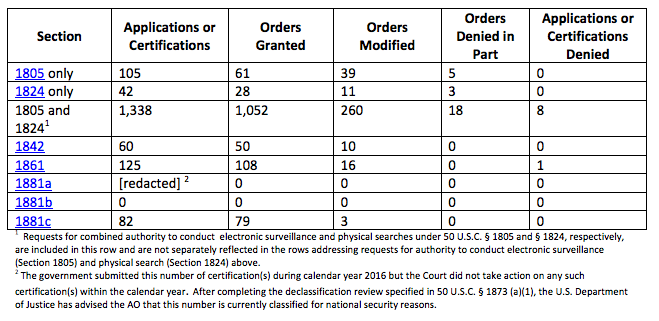

FISC did not (necessarily) reject more individual orders last year

First, let’s talk about what the FISC report is. It is a new report, mandated by the USA Freedom Act. As the report itself notes, because it is new (a report covering the period after passage of USAF), it can’t be compared with past years. More importantly, because the FISA Court uses a different (and generally more informative) reporting approach, you cannot — as both privacy groups and journalists erroneously have — compare these numbers with the DOJ report that has been submitted for years (or even the I Con the Record report that ODNI has released since the Snowden leaks); that’s effectively an apples to grapefruit comparison. Those reports should be out this week, which (unless the executive changes its reporting method) will tell us how last year compared with previous years.

But comparing last year’s report to the report from the post-USAF part of 2015 doesn’t sustain a claim that last year had record rejections. If we were to annualize last year’s report (covering June to December 2015) showing 5 rejected 1805/1824 orders (those are the individual orders often called “traditional FISA”) across roughly 7 months, it is actually more (.71 rejected orders a month or .58% of all individual content applications) than the 8 rejected 1805/1824 orders last year (.67 rejected orders a month or .53% of all individual content applications). In 2016, the FISC also rejected an 1861 order (better known as Section 215), but we shouldn’t make too much of that either given that that authority changed significantly near the end of 2015, plus we don’t have this counting methodology for previous years (as an example, 2009 almost surely would have at least one partial rejection of an entire bulk order, when Reggie Walton refused production of Sprint records in the summertime).

Which is a long-winded way of saying we should not assume that the number of traditional content order rejections reflects the reports that FBI applied for orders on four Trump associates but got rejected (or maybe only got one approved for Page). As far as we can tell from this report, 2016 had a similar number of what FISC qualifies as rejections as 2015.

The non-approval of Section 702 certificates has no bearing on any Russian-related spying, which means Page would be subject to back door searches

Nor should my observation — that the FISC did not approve any certifications for 1881a (better known as Section 702, which covers both upstream and PRISM) reflect on any Carter Page surveillance. Given past practice when issues delayed approvals of certifications, it is all but certain FISC just extended the existing certifications approved in 2015 until the matters that resulted in an at least 2 month delay were resolved.

Moreover, the fact that the number of certificates (which is probably four) is redacted doesn’t mean anything either: it was redacted last year as well. That number would be interesting because it would permit us to track any expansions in the application of FISA 702 to new uses (perhaps to cover cybersecurity, or transnational crime, for example). But the number of certificates pertains to the number of people targeted only insofar as any additional certificates represent one more purpose to use Section 702 on.

In any case, Snowden documents, among other things, show that a “foreign government” certificate has long been among the existing certificates. So we should assume that the NSA has collected the conversations of known or suspected Russian spies located overseas conducted on PRISM providers; we should also assume that as a counterintelligence issue implicating domestic issues, these intercepts are routinely shared in raw form with FBI. Therefore, unless last year’s delay involved FBI’s back door searches, we should assume that when the FBI started focusing on Carter Page again last spring or summer, they would have routinely searched on his known email addresses and phone numbers in a federated search and found any PRISM communications collected. In the same back door search, they would have also found any conversations Page had with Russians targeted domestically, such as Sergey Kislyak.

The import of the breakdown between 1805 and 1824

Perhaps the most important granular detail in this report — one that has significant import for Carter Page — is the way the report breaks down authorizations for 1805 and 1824.

1805 covers electronic surveillance — so the intercept of data in motion. It might be used to collect phone calls and other telephony communication, as well as (perhaps?) email communication collected via upstream collection (that is, non-PRISM Internet communication that is not encrypted); it may well also cover prospective PRISM and other stored communication collection. 1824 covers “physical search,” which when it was instituted probably covered primarily the search of physical premises, like a house or storage unit. But it now also covers the search of stored communication, such as someone’s Gmail or Dropbox accounts. In addition, a physical search FISA order covers the search of hard drives on electronic devices.

As we can see for the first time with these reports, most individual orders cover both 1805 and 1824 (92% last year, 88% in 2015), but some will do just one or another. (I wonder if FBI sometimes gets one kind of order to acquire evidence to get the other kind?)

As filings in the Keith Gartenlaub case make clear, “physical search” conducted under a FISA order can be far more expansive than the already overly expansive searches of devices under a Article III warrant. Using a FISA 1824 order, FBI Agents snuck into Gartenlaub’s house and imaged the hard drives from a number of his devices, ostensibly looking for proof he was spying on Boeing for China. They found no evidence to support that. They did, however, find some 9-year old child pornography files, which the government then “refound” under a criminal search warrant and used to prosecute him. Among the things Gartenlaub is challenging on appeal is the breadth of that original FISA search.

Consider how this would work with Carter Page. The NYT story on the Page order makes it clear that FBI waited until Page had left the Trump campaign before it requested an order covering him.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court issued the warrant, the official said, after investigators determined that Mr. Page was no longer part of the Trump campaign, which began distancing itself from him in early August.

I suspect this is a very self-serving description on the part of FBI sources, particularly given reports that FISC refused orders on others. But regardless of whether FISC or the FBI was the entity showing discretion, let’s just assume that someone was distinguishing any communications Page may have had while he was formally tied to the campaign from those he had after — or before.

This is a critical distinction for stored communications because (as the Gartenlaub case makes clear) a search of a hard drive can provide evidence of completely unrelated crime that occurred nine years in the past; in Gartenlaub’s case, they reportedly used it to try to get him to spy on China and they likely would do the equivalent for Page if they found anything. For Page, a search of his devices or stored emails in September 2016 would include emails from during his service on Trump’s campaign, as well as emails between the time Page was interviewed by FBI on suspicion of being recruited by Victor Podobnyy and the time he started on the campaign, as well as communications going back well before that. So if FISC (or, more generously, the FBI) were trying to exclude materials from during the campaign, that might involve restrictions built into the request or the final order

The report covering 2016 for the first time distinguishes between orders FISC modifies (FISC interprets this term more broadly than DOJ has in its reports) and orders FISC partly denies. FISC will modify an order to, among other things,

(1) impos[e] a new reporting requirement or modifying one proposed by the government;

(2) chang[e] the description or specification of a targeted person, of a facility to be subjected to electronic surveillance or of property to be searched;

(3) modify[] the minimization procedures proposed by the government; or

(4) shorten[] the duration of some or all of the authorities requested

Using Page as an example, if the FISC were permitting FBI to obtain communications from before the time Page joined the campaign but not during it, it might modify an order to require additional minimization procedures to ensure that none of those campaign communications were viewed by the FBI.

The FISC report explains that the court will partly deny orders and “by approving some targets, some facilities, places, premises, property or specific selection terms, and/or some forms of collection, but not others.” Again, using Page as an example, if the court wanted to really protect the election related communications, it might permit a search of Page’s homes and offices under 1824, but not his hard drives, making any historic searches impossible.

There’s still no public explanation of how Section 704/Section 705b work, which would impact Page

Finally, the surveillance of Carter Page implicates an issue that has been widely discussed during and since passage of the FISA Amendments Act in 2008, but not in a way that fully supports a democratic debate: how NSA spies on Americans overseas.

Obviously, the FBI would want to spy on Page both while he was in the US, but especially when he was traveling abroad, most notably on his frequent trips to Russia.

The FISA Amendments Act for the first time required the NSA to obtain FISC approval before doing that. As I explain in this post, for years, public debate has claimed that was done under Section 703 (1881b in this report). But abundant evidence shows it is all done under 704 (1881c in this report). The biggest difference between the two, according to an internal NSA document, is the government doesn’t explain its methods in the latter case. With someone who would be spied on both in the US and overseas, that spying would be done under 705b (conducted under 1881d section b), which permits the AG to approve of spying overseas (effectively, 704 authority) for those already approved under a traditional order.

This matters in the context of spying on Carter Page for two reasons. First, as noted government doesn’t share details about how it spies overseas with the court. And some of the techniques we know NSA to use — such as XKeyscore searches drawing on bulk overseas collection — would seem to present additional privacy concerns on top of the domestic authorities. If the FBI (or more likely, the FISC) is going to try to bracket off any communications that occur during the period Page was associated with the campaign, that would have to be done for overseas surveillance as well, most critically, for Page’s July trip to Russia.

This report shows that 704, like the domestic authorities, also gets modified sometimes, so it may be that FISC did just that — permitted NSA to collect information covering that July meeting, but imposed some minimization procedures to protect the campaign.

But it’s unclear whether the court would have an opportunity to do so for 705b, which derives from Attorney General authorization, not court authorization. I assume that’s why 1881d was not included in this reporting requirement, but it seems adding 705b reporting to Title VII reauthorization this year would be a fairly minor change, but one that might reveal how often the government uses more powerful overseas spying techniques on Americans. It’s unclear to me, for example, whether any modifications or partial approvals the FISC made on a joint 1805/1824 order covering Page would translate into a 705b order, particularly if the modifications in question included additional reporting to the FISC.

Carter Page might one day be the first American to get review of his FISA dossier

All of which is why, no matter what you think of Carter Page’s alleged role in influencing the Trump campaign to favor Russia, I hope he one day gets to review his FISA dossier.

No criminal defendant has ever gotten a review of the FISA materials behind the spying, in spite of clear Congressional intent, when the law was passed in 1978, to allow that in certain cases. Because of the publicity surrounding this case, and the almost unprecedented leaking about FISA orders, Page stands a better chance than anyone else of getting such review (particularly if, as competing stories from CNN and Business Insider claim, the dossier formed a key, potentially uncorroborated part of the case against him). Whatever else happens with this case, I think Page should get that review.

OT?: WitchHunt? Misdirection? Fakenews?

http://www.cbsnews.com/news/cia-fbi-on-manhunt-for-leaker-who-gave-top-secret-documents-to-wikileaks/

Why joint FBI-CIA investigation?

Why is NSA not involved? (that is a tell)

Why look for an insider that is no longer there?

Why did Pompeo rail about WL and Russia last week, and now has seemingly bought a vowel?

“The agency has not said publicly when the material was taken or how it was stolen.”

[That could be because they have no clue.

Chasing ghosts at this point. I have my theory, and this investigation, if even really happening, will lead nowhere except to more bad intel]

OT: Rule 41 usage

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2017/04/fbi-allays-some-critics-with-first-use-of-new-mass-hacking-warrant/

The FBI “had to infect machines,” convert them into so-called supernodes that distribute connection lists to other victimized computers, and then “poison” all the computers so they would never again try to communicate with hacker-controlled devices, said Bambenek, who also assisted on the 2014 Gameover Zeus cleansing operation.