FBI’s Surveillance Arbitrage, First Amendment Edition

While I was cycling around Provence without a care in the world last week, DOJ’s Inspector General released an IG Report mandated by the USA Freedom Act. It reports on the use of Section 215 from 2012 to 2014 (which means NSA and FBI have successfully avoided any review of their 215 orders from 2010 and 2011, not to mention any review of CIA’s use of the provision). The key takeaway is that the application process to get Section 215 orders is very time consuming — over 100 days on average. Which is probably why Republican Senators have been trying to permit FBI to obtain Electronic Communications Transaction Records with just a National Security Letter since the report was released to Congress in June.

The report also noted a sharp drop-off in the use of 215 orders in recent years, which I’ve been tracking here.

Those two factors are useful background for some other details in the report, however. First, DOJ and FBI interviewees offered many explanations for the decline in Section 215 use, one of which is Edward Snowden, but two more credible ones of which are the use of other authorities to get the same information, Section 702 or grand jury subpoenas.

NSD and FBI personnel attributed the subsequent decline between 2013 and 2015 to several factors, including the stigma attached to the use of Section 215 authority following the Snowden revelations, increased use of Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act, providers’ resistance to business records orders, agents’ frustrations with the lack of timeliness and level of oversight in the business records process, and agents’ increasing use of criminal legal process instead of FISA authority in counterterrorism and cyber investigations.

They key point, though, is for most uses, there are other ways to get the same information. There is a limit to that, though. Apparently, grand jury subpoenas are only possible for counterterrorism and cybersecurity investigations, not counterintelligence ones.

When asked about this disparity, agents told us that business records orders frequently are the only option available in counterintelligence investigations given the nature and classification of the information involved. By contrast, agents handling counterterrorism and cyber investigations can in some instances open a parallel criminal investigation and use the grand jury process to obtain the same information more quickly and with less oversight than a business records order.

That’s why I’m so interested in a discussion of the applications that got filed — in counterterrorism cases — but either not submitted or withdrawn from the FISC in this period.

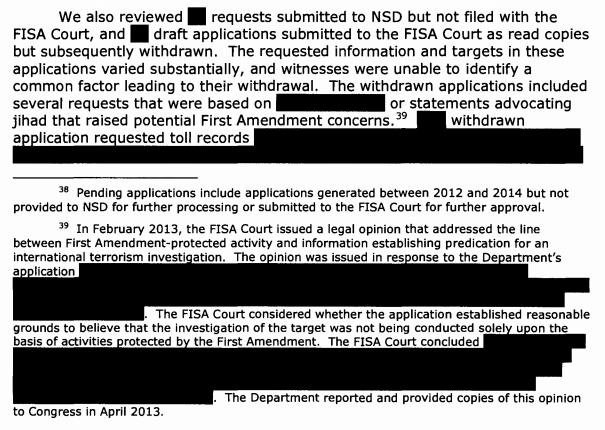

Remember, the way the government and FISC avoid rejected applications is by not submitting or withdrawing things that it is clear the FISC won’t approve. What this redacted section effectively says is that at least “several” requests based on a target’s statements about jihad were withdrawn, apparently in the wake of a February 2013 order from John Bates on what constitutes targeting for First Amendment reasons.

We’ve seen a heavily redacted version of that opinion. As I laid out here, it’s a classic John Bates opinion: it hems and haws about Executive Branch behavior, but then approves the behavior in question (at least in this case, Bates didn’t approve an expansion of the questionable behavior, as he did in 2010 with the Internet dragnet).

Effectively Bates appears to have objected to the use of a target’s language (perhaps, support for jihad without endorsement of specific threats) in obtaining a Section 215 order, but then pointed to other peoples’ behavior in finding that the order didn’t stem exclusively from First Amendment protected activities.

And the IG Report says that, apparently in the wake of that wishy-washy opinion, DOJ decided to withdraw several applications based on stated support for jihad.

Remember, in 2006, the FBI withdrew two attempts at a 215 order because of FISC’s First Amendment concerns only to get the same information with NSLs. (See page 68ff) Congress made a particularly big stink about it, because the FBI was acting on its own in spite of FISC’s disapproval.

This feels similar. That is, given that FBI was already moving its Section 215 orders to grand jury subpoenas because they’re easier to get and undergo less oversight, it sure seems likely these requests reappeared as such. Unlike the earlier IG report that confirmed FBI arbitraged surveillance authorities to get around First Amendment protections, this report appears not to have pursued the issue (as I understand it, the declassification of this report was handled exclusively through redactions).

They did, however, ask why DOJ doesn’t track applications that are withdrawn, to avoid the appearance that the FISC is a rubber stamp. DOJ’s answer was rather unpersuasive.

The FISA Court did not deny any business records applications between 2012 and 2014. When asked why applications withdrawn after submission of a read copy to the FISA Court were not reported to Congress, potentially creating the inadvertent impression that the FISA Court is a “rubber stamp,” NSD supervisors told us that the Department includes only business records applications formally submitted to the FISA Court and denied or withdrawn, not those filed in “read copy” and subsequently withdrawn. 41 The NSD supervisors acknowledged that excluding applications withdrawn after the FISA Court indicates that it will not sign an order might lead to misunderstandings about the FISA Court’s willingness to question applications, but the supervisors noted that NSD and the FISA Court have talked about the “read” process publicly to address concerns about this. 42 In comments provided to the OIG after reviewing a draft of this report, NSD stated that it is currently considering whether to revise the methodology for counting withdrawn applications.

My guess is they want to avoid any records of withdrawn applications for those times when they do use a grand jury subpoena to obtain stuff that FISC made known it wouldn’t approve. That detail might have to be disclosed to defendants, after all. Here, there’s less paperwork.

It all seems to support a theory that the FBI continues to arbitrage surveillance authorities (as they, by their own admission, do with location tracking). With location tracking, there’s nothing patently illegal about that. But with First Amendment protections, that sure seems dubious.